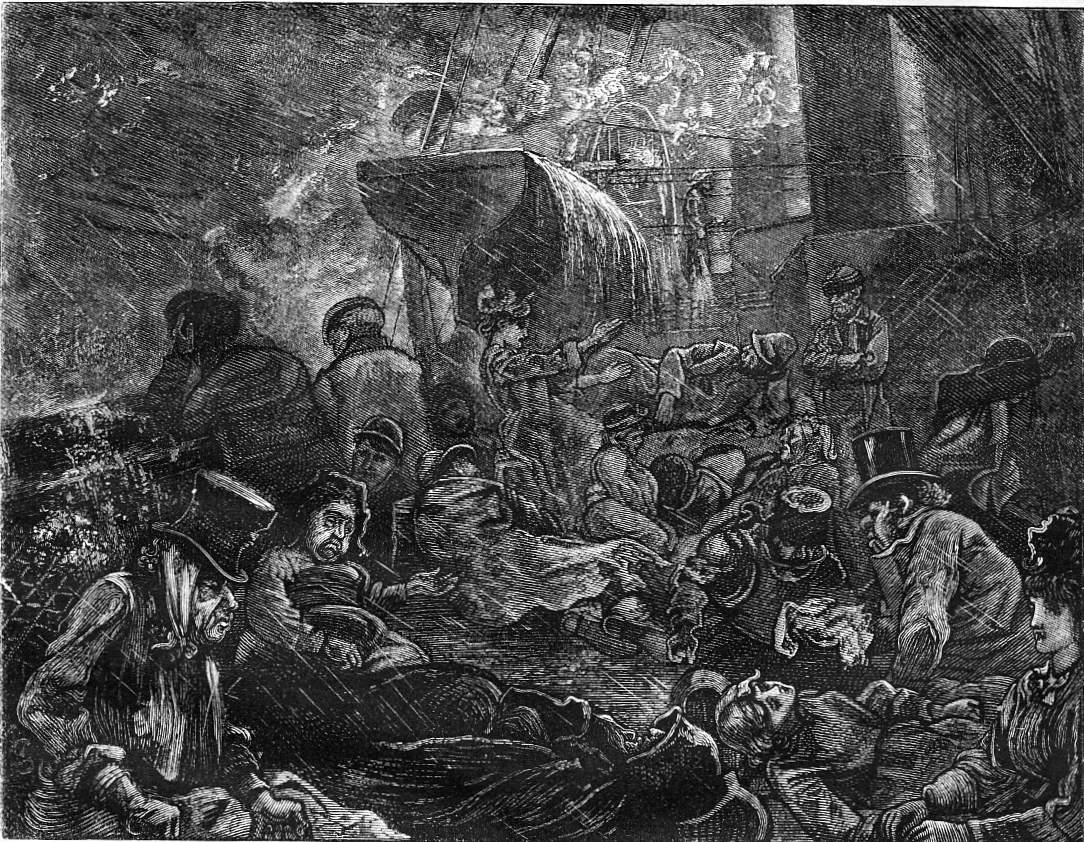

"The wind blows stiffly from the Nor-East, the sea runs high, we ship a deal of water, the night is dark and cold, and the shapeless passengers lie about in melancholy bundles." by Edward G. Dalziel. Wood engraving. From Dickens's "Calais Night-Mail," chapter 17 in The Uncommercial Traveller. [Click on image to enlarge it.]

Passage Realized

Bright patches break out in the train as the doors of the post-office vans are opened, and instantly stooping figures with sacks upon their backs begin to be beheld among the piles, descending as it would seem in ghostly procession to Davy Jones's Locker. The passengers come on board; a few shadowy Frenchmen, with hatboxes shaped like the stoppers of gigantic case-bottles; a few shadowy Germans in immense fur coats and boots; a few shadowy Englishmen prepared for the worst and pretending not to expect it. I cannot disguise from my uncommercial mind the miserable fact that we are a body of outcasts; that the attendants on us are as scant in number as may serve to get rid of us with the least possible delay; that there are no night-loungers interested in us; that the unwilling lamps shiver and shudder at us; that the sole object is to commit us to the deep and abandon us. Lo, the two red eyes glaring in increasing distance, and then the very train itself has gone to bed before we are off!

What is the moral support derived by some sea-going amateurs from an umbrella? Why do certain voyagers across the Channel always put up that article, and hold it up with a grim and fierce tenacity? A fellow-creature near me — whom I only know to be a fellow-creature, because of his umbrella: without which he might be a dark bit of cliff, pier, or bulkbead — clutches that instrument with a desperate grasp, that will not relax until he lands at Calais. Is there any analogy, in certain constitutions, between keeping an umbrella up, and keeping the spirits up? A hawser thrown on board with a flop replies "Stand by!" "Stand by, below!" "Half a turn a head!" "Half a turn a head!" "Half speed!" "Half speed!" "Port!" "Port!" "Steady!" "Steady!" "Go on!" "Go on!"

A stout wooden wedge driven in at my right temple and out at my left, a floating deposit of lukewarm oil in my throat, and a compression of the bridge of my nose in a blunt pair of pincers, — these are the personal sensations by which I know we are off, and by which I shall continue to know it until I am on the soil of France. My symptoms have scarcely established themselves comfortably, when two or three skating shadows that have been trying to walk or stand, get flung together, and other two or three shadows in tarpaulin slide with them into corners and cover them up. Then the South Foreland lights begin to hiccup at us in a way that bodes no good.

It is at about this period that my detestation of Calais knows no bounds. Inwardly I resolve afresh that I never will forgive that hated town. I have done so before, many times, but that is past. Let me register a vow. Implacable animosity to Calais everm — that was an awkward sea, and the funnel seems of my opinion, for it gives a complaining roar.

The wind blows stiffly from the Nor-East, the sea runs high, we ship a deal of water, the night is dark and cold, and the shapeless passengers lie about in melancholy bundles, as if they were sorted out for the laundress; but for my own uncommercial part I cannot pretend that I am much inconvenienced by any of these things. A general howling, whistling, flopping, gurgling, and scooping, I am aware of, and a general knocking about of Nature; but the impressions I receive are very vague. In a sweet faint temper, something like the smell of damaged oranges, I think I should feel languidly benevolent if I had time. [83-84]

Commentary

The sombre, almost purgatorial composition of the dark plate — or, at least, a wood-engraving emulating the dark, steel-etched plates of Phiz for Bleak House — communicates effectively the misery which the deck passengers on the Channel ferry experience in Dickens's essay "The Calais Night Mail," first published in All the Year Round on 2 May 1863, a follow up to a Household Words article on the South Eastern Railway's 'Special Express train and Steam ship' service between London and Paris via Dover and Calais (August 1851). As Slater and Drew note, however, these articles draw on Dickens's "memories of cross-Channel trips going back to his first journey abroad in July 1837" (209). Finally, the date of publication suggests not visits to see his sons at school in Boulogne ("Our French Watering Place" of Household Words in 1854), but to spend stolen days with his young mistress, the actress Ellen Ternan, at the spacious farmhouse he had leased at the out-of-the-way village of Condette early in 1863.

Transforming technical nautical language into images of commercial shipping and smacking of the social realism of the East End scenes of Luke Fildes and Fred Barnard, Dalziel's illustration emphasizes the sufferings of travellers who come from below the level of the comfortable middle classes. Dickens refers to the deck passengers as "outcasts" — a mixed company of men and women, mature and elderly, and of three nationalities: French, English, and German. And the "Uncommercial" narrator identifies himself (and therefore his readers with these unfortunate travellers by speaking as if he is one of them: "we" and "us" (83) reveal his sympathy and control the readers' sympathies. Dalziel's visual complement shifts the perspective from the first person to the dramatic, letting us inspect these figures as if they were sufferers on Géricault's monumental The Raft of the Medusa (1818-19). Seeming to be harbingers of the vessel's destruction, churning waves pour over the lifeboat (upper centre), powerfully realizing the understatement "we ship a deal of water" (84) as some twenty male and female figures representative of the lower orders struggle to remain warm and dry as they try to sleep out their passage in the Dante-esque semi-darkness. The tone of the illustration, then, foils the cheerfulness of the narrator, presenting a counter-view to his essential optimism.

Scanned image by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Dickens, Charles. The Uncommercial Traveller, Hard Times, and The Mystery of Edwin Drood. Il. Charles Stanley Reinhart and Luke Fildes. The Household Edition. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1876.

Dickens, Charles. The Uncommercial Traveller. Il. Edward Dalziel. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1877.

Hartnoll, Phyllis, ed. The Concise Oxford Companion to the Theatre. Oxford and New York: Oxford U. P., 1972.

Scenes and Characters from the Works of Charles Dickens; being eight hundred and sixty-six drawings, by Fred Barnard, Hablot Knight Browne (Phiz); J. Mahoney; Charles Green; A. B. Frost; Gordon Thomson; J. McL. Ralston; H. French; E. G. Dalziel; F. A. Fraser, and Sir Luke Fildes; printed from the original woodblocks engraved for "The Household Edition." New York: Chapman and Hall, 1908. Copy in the Robarts Library, University of Toronto.

Slater, Michael, and John Drew, eds. Dickens' Journalism: 'The Uncommercial Traveller' and Other Papers 1859-70. The Dent Uniform Edition of Dickens' Journalism, vol. 4. London: J. M. Dent, 2000.

Last modified 3 March 2013