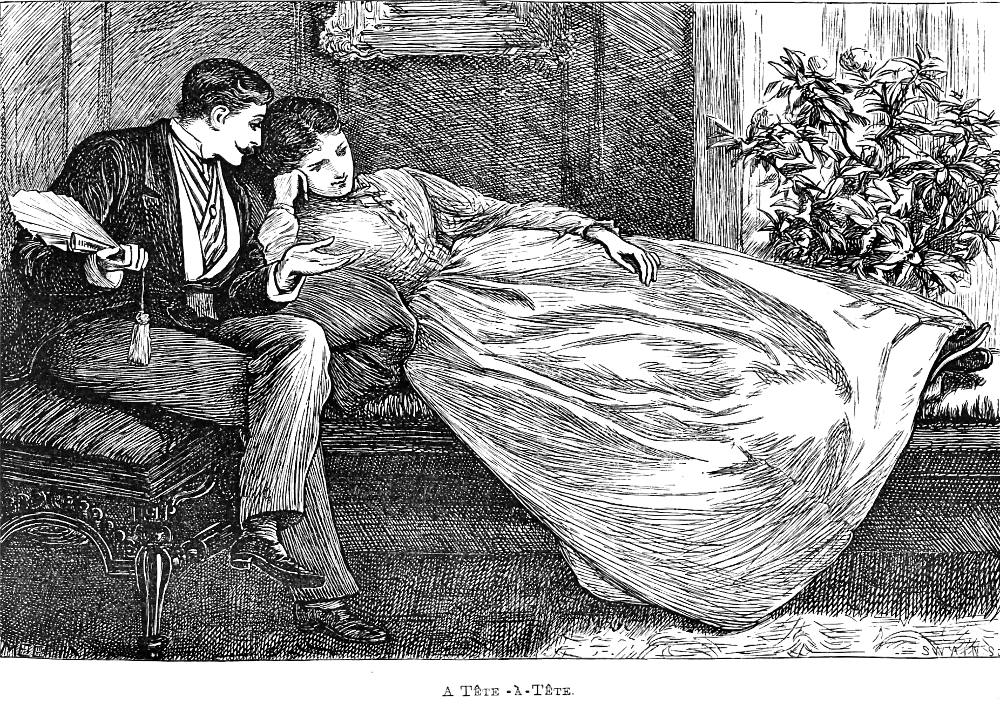

A Tête-à-Tête (Vol. XVII, facing page 641), horizontally-mounted, 10.5 cm high by 16.1 cm wide (4 ⅛ by 6 ¼ inches), framed; signed "MEE." in the lower-left corner. Mary Ellen Edwards' wood-engraving for Charles Lever's The Bramleighs of Bishop's Folly in the Cornhill Magazine (June 1868), Chapters XLVIII-LI ("A Telegram" through "Some News from Without") in Vol. 17: pages 641 through 663 (23 pages including unpaged illustration in instalment). The wood-engraver responsible for this illustration was Joseph Swain (1820-1909), noted for his engravings of Sir John Tenniel's cartoons in Punch. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Passage Illustrated: Lady Augusta and "Count" Pracontal join forces

Pracontal was now seated on a low stool beside her sofa, and fanning her assiduously.

“Not but these people are all right,” continued she. “It is quite wrong in me to admit you to my intimacy — wrong to admit you at all. My sister is so angry about it she won't come here — fact, I assure you. Now don't look so delighted and so triumphant, and the rest of it. As your nice little phrase has it, you 'are for nothing' in the matter at all. It is all myself, my own whim, my fancy, my caprice. I saw that the step was just as unadvisable as they said it was. I saw that any commonly discreet person would not have even made your acquaintance, standing as I did; but unfortunately for me, like poor Eve, the only tree whose fruit I covet is the one I'm told isn't good for me. There go our friends once more. I wish I could tell her who you are, and not keep her in this state of torturing anxiety.”

“Might I ask, my Lady,” said he, gravely, “if you have heard anything to my discredit or disparagement, as a reason for the severe sentence you have just spoken?”

“No, unfortunately not; for in that case my relatives would have forgiven me. They know the wonderful infatuation that attracts me to damaged reputations, and as they have not yet found out any considerable flaw in yours, they are puzzled, out of all measure, to know what it is I see in you.” [Chapter XLIX, "A Long Tête-à-Tête," 653 in serial; pp. 329-330 in volume]

Commentary: Flirting with the Enemy

Ever since the Countess Balderoni's reception in Chapter Forty, the flirtatious Lady Augusta and the dashing Count "Pracontal de Bramleigh" (as he now styles himself) have been much together, including on nearly daily rides throughout Campagna. She seems to enjoy his presence for the galling effect that it has on her stepdaughter Marion, the young wife of diplomat Lord Culduff. She is thus disappointed when the Culduffs decamp for Naples, where the diplomat is accredited, rather than attend her dinner with their continental cousin. Rather than buy him off for twenty-thousand pounds, Augustus has elected to challenge Pracontal's claim in court, so that he is now the legal adversary of the Bramleighs. And the letter he reads her from his attorney leads him to believe that he will ultimately triumph: "Kelson tells me success is certain."

In these intimate conversations between Pracontal and Lady Augusta we learn in detail about his family history, which of course has direct bearing on his claims to being the legitimate heir to the Bramleigh fortunes as his grandmother (the beautiful daughter of an italian painter named Giacomo Lami) had married Montague Bramleigh and had given birth to Pracontal's father well before the recently deceased Colonel Bramleigh was born. The figure whom we see in this Edwards illustration is perfectly consistent with the description which Julia L'Estrange offers of him at the Christmas dinner in Albano thrown by the L'Estranges for Augustus and Ellen Bramleigh, recently arrived:

“Like a very well-bred Frenchman of the worst school of French manners: he has none of that graceful ease and that placid courtesy of the past period, but he has abundance of the volatile readiness and showy smartness of the present day. They are a wonderful race, however, and their smattering is better than other men's learning.” [Chapter XLV, "A Pleasant Dinner," 300 in volume]

Thus, Edwards draws material for other chapters in her portrait of the "pretender" who seems to be on the brink of victory in his lawsuit with the Bramleighs.

Commentary: Pracontal's Apparent Age and Dating the Action of the Novel (1855?)

Just how old is Count Pracontal? Although he appears no more than forty in the present illustration, the French Ambassador to Rome reveals that they were fellow officers in France’s African campaign (not that of 1798-1801, but the Algerian campaigns led by Marshal Pélissier beginning in 1830); moreover, Lever alludes to Somerset House (1831 onwards), Queen Victoria (1837 onwards), and France’s Second Empire (1852-1870). Since none of Lever's many references to America include the Civil War, the novel seems to be set prior to 1860 — in which case Count Pracontal may be anything up to forty years of age, which would be consistent with this figure in Edwards’ illustrations and Lever’s descriptions of the suave French aristocrat; certainly he must be somewhat younger than fifties-something Lady Augusta, whom Edwards nevertheless depicts in A Tête-à-Tête as considerably younger.

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Lever, Charles. The Bramleighs of Bishop’s Folly. The Cornhill Magazine 15 (June, 1867): pp. 640-664; 16 (July-December 1867): 1-666; 17 (January-June 1868): 1-663; 18 (July-October 1868): 1-403. Rpt. London: Chapman & Hall, 1872. Illustrated by M. E. Edwards; engraved by Joseph Swain.

Stevenson, Lionel. "Chapter XVI: Exile on the Adriatic, 1867-1872." Dr. Quicksilver: The Life of Charles Lever. London: Chapman and Hall, 1939. Pp. 277-296.

Created 9 September 2023