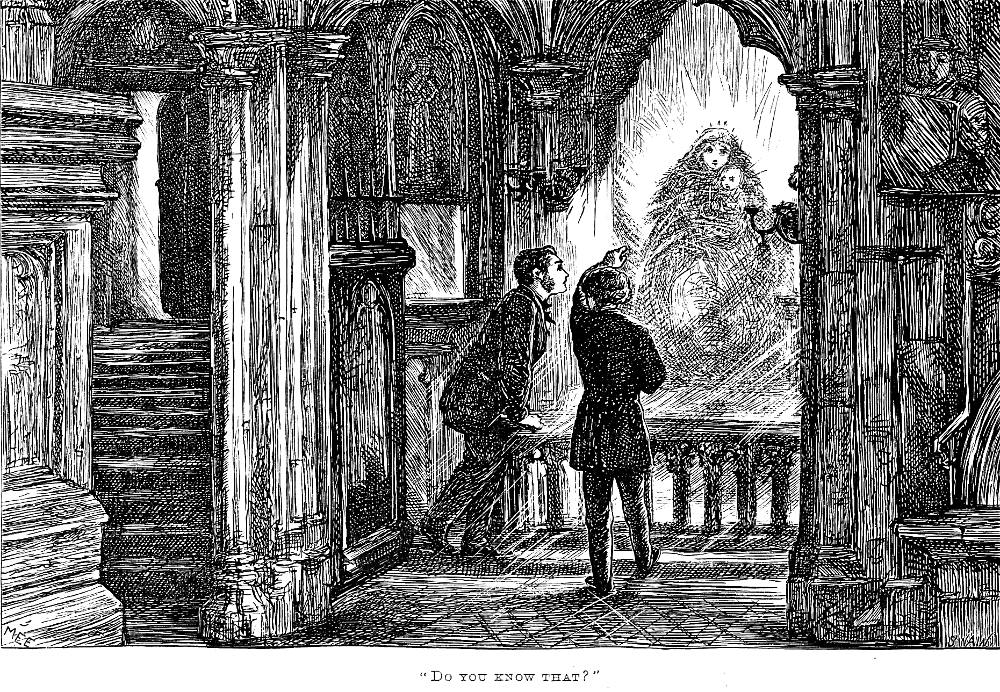

"Do you know that?" (Vol. XVIII, facing page 257), horizontally-mounted, 10.5 cm high by 16.2 cm wide (4 ⅛ by 6 ¼ inches), framed; signed "MEE." in the lower-left corner. Mary Ellen Edwards' wood-engraving for Charles Lever's The Bramleighs of Bishop's Folly in the Cornhill Magazine (September 1868), Chapters LXI-LXV ("Lady Cudluff's Letter" through "The Light Stronger") in Vol. 18: pages 257 through 280 (23 pages including unpaged illustration in instalment). The wood-engraver responsible for this illustration was Joseph Swain (1820-1909), noted for his engravings of Sir John Tenniel's cartoons in Punch. [Click on the image to enlarge it; mouse over links.]

Passage Illustrated: Jack and Cutbill explore what lies behind the chapel's grill

By the time Cutbill had reached the entrance, Jack had succeeded in opening the massive doors; and as he flung them wide, a flood of light poured into the little crypt, with its splendid altar and its silver lamps; its floor of tessellated marble, and its ceiling a mass of gilded tracery almost too bright to look on: but it was not at the glittering splendour of gold or gems that they now stood enraptured. It was in speechless wonderment of the picture that formed the altar-piece, which was a Madonna, — a perfect copy, in every lineament and line, of the Flora at Castello. Save that an expression of ecstatic rapture had replaced the look of joyous delight, they were the same, and unquestionably were derived from the same original.

“Do you know that?” cried Cutbill.

“Know it! Why, it's our own fresco at Castello.”

“And by the same hand, too,” cried Cutbill. “Here are the initials in the corner, — G. L.! Of all the strange things that I have ever met in life, this is the strangest!” And he leaned on the railing of the altar, and gazed on the picture with intense interest.

“I can make nothing of it,” muttered Jack.

“And yet there's a great story in it,” said Cutbill, in a low, serious tone. “That picture was a portrait, — a portrait of the painter's daughter; and that painter's daughter was the wife of your grandfather, Montague Bramleigh; and it is her grandchild now, the man called Pracontal, who claims your estates.”

“How do you pretend to know all this?” [Chapter LXIV, "A First Gleam of Light," 273 in serial; pp. 419-420 in volume]

Commentary: The Plot Secret Lies in the Chapel Mural at Catarro, Montenegro

As early as Chapter L, "Catarro," Lever lays the groundwork for this discovery scene at the Venetian chapel on the grounds of the Villa Fontanella that Augustus has leased for three years from the grubby Count who owns it:

This chapel was only used once a year, when a mass for the dead was celebrated, so that the Count insisted no inconvenience could be incurred by the tenant. Indeed, he half hinted that, if that one annual celebration were objected to, his ancestors might be prayed for elsewhere, or even rest satisfied with the long course of devotion to their interests which had been maintained up to the present time. As for the chapel itself, he described it as a gem that even Venice could not rival. There were frescos of marvellous beauty, and some carvings in wood and ivory that were priceless. Some years back he had employed a great artist to restore some of the paintings, and supply the place of others that were beyond restoration; and now it was in a state of perfect condition, as he would be proud to show them. [Chapter L, "Catarro," 334 in volume]

At this point, however, perhaps to avoid letting the cat out of the bag, so to speak, Lever's Montenegrin Count had failed to mention the name of the fresco painter in charge of the mural's restoration: Giacomo Lami. And this earlier chapter had mentioned that Lami had hidden some crucial papers “Behind this stone. . . .” In Chapter LII, "Ischia," old No. 97 (likely Pracontal's father, not dead but sentenced to hard labour for his part in an assassination plot) tells No. 11 (likely Jack Bramleigh, using the pseudonym "Samuel Rogers") that "old Giacomo Lami . . . never painted his daughter Enrichetta in a fresco, that he didn't hide gold, or jewels, or papers of value somewhere near. Tell him, above all, to find out where Giacomo's last work was executed" (344 in volume). Julia completes the translation for Sedley in the scene in the vignette for this number by indicating that the boy, Lami's first grandson, died at the age of four, and was buried in a pauper's grave in Savoy. Consequently, Pracontal cannot possibly be the blood descendant of Montague Bramleigh. But there is a further plot twist.

The scene had shifted to the chapel a mile away from the villa because Nelly had proposed that the family hide their all-too-candid visitor, Mr. Cutbill, there while the attorney, Sedley, is seeking Augusts's direction regarding Practonal's latest proposal — to permit the Bramleighs to continue to live at Castello, "merely paying him a rentcharge of four thousand a year" (Chapter LXIII, "The Client and His Lawyer," 413 in volume). However, Augustus is determined to have all (if the law supports his claim) or nothing, and elects to have Sedley reject the "partition of the property." But now, as all seems lost, Cutbill and Jack discover the mural in the chapel, and afterwards the oak box under the flag-stones of the altar-steps. Its documents suggest that the old galley slave, with whom Jack was chained at Ischia, and not Pracontal (otherwise, Tonino Baldassare) is the legitimate claimant. The old prisoner himself appears in the next full-page illustration, A Meeting, in the final monthly number (October 1868).

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Lever, Charles. The Bramleighs of Bishop’s Folly. The Cornhill Magazine 15 (June, 1867): pp. 640-664; 16 (July-December 1867): 1-666; 17 (January-June 1868): 1-663; 18 (July-October 1868): 1-403. Rpt. London: Chapman & Hall, 1872. Illustrated by M. E. Edwards; engraved by Joseph Swain.

Stevenson, Lionel. "Chapter XVI: Exile on the Adriatic, 1867-1872." Dr. Quicksilver: The Life of Charles Lever. London: Chapman and Hall, 1939. Pp. 277-296.

Created 7 September 2023