This review is reproduced here by kind permission of the online inter-disciplinary journal Cercles, where it was first published. The original text has been reformatted and illustrated for the Victorian Web by Jacqueline Banerjee, who has also added links and captions. Click on the images for larger pictures and more information where available.

"It is not the politician that makes the caricaturist, but the caricaturist that makes the politician" (7).

A major figure in late-Victorian and Edwardian literary and artistic circles, Harry Furniss (1854–1925) is well-known for his contributions to illustrated periodicals such as Punch and The Graphic. From 1880 to 1894, he produced hundreds of cartoons for Henry Lucy's weekly political column, "The Essence of Parliament," providing the Punch readership with visual representation of the parliamentary world. Partly inspired from these vignettes, The Humours of Parliament was an illustrated lecture-entertainment which Furniss staged throughout the UK, North America and Australia during the 1890s, constantly revising it in the course of its repeated performance.

In an attempt to call renewed attention to the art of Furniss whose "career and place in late-Victorian and Edwardian public culture are now almost entirely neglected" (2), Gareth Cordery and Joseph S. Meisel, both specialists of Victorian political and literary culture, have published an edited version of the text. The aim of The Humours of Parliament: Harry Furniss's View of Late-Victorian Culture is to present Furniss's unpublished oral performance for the first time as well as to position the author-illustrator within the broader artistic, political and historical context of his time.

Two illustrations for Henry Lucy's weekly political column, "The Essence of Parliament," in Punch. Left: "Rehearsal for Opening Day," showing politicians rousing themselves for a new session, under the auspices of the Lord Chancellor, and the direction of the Speaker (11 Feb. 1888, 71). Right: The caption here is, "Increased facilities are provided for Ladies dining, &c., with Members." In the top left-hand corner, the smoking room is shown as deserted. A "family party," complete with children and a pot of jam, is taking place below it instead (25 Feb. 1888), 95)

The volume, 326 pages long, consists of the annotated lecture itself together with a six-chapter editorial introduction encompassing pictorial conventions, political culture and communication, the unfolding of the performance itself and the adaptation of the show for specific audiences. A series of appendices, successively devoted to Furniss's lecture preparations, choice of images and itineraries throughout the UK (1891), North America (1896-97) and Australia (1897) completes this extremely well-documented approach, together with an exhaustive and clearly organised bibliography and a thorough index of entries. Some 157 vignettes taken from Furniss's considerable black-and-white production for various magazines of the time – Punch and The Graphic, mainly, but also lesser-known and/or shorter-lived periodicals such as Lika Joko, Good Words, Fair Game or The Illustrated English Magazine — complete this book.

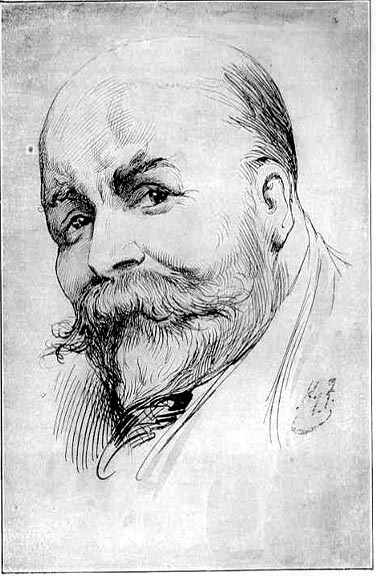

Self-portrait by Furniss, 1910.

"Harry Furniss, Life in Art," first of the six introductory chapters, seeks to position the artist within the tradition of British political caricature. This part retraces Furniss's career, stressing the artist's satirical heritage (Gillray, Rowlandson and the Regency caricaturists) and highlighting his role in publicizing Parliament for his audience. Furniss's somewhat paradoxical positioning to his own art — "[...] regretting the less savage form of caricature required by the times [but seeking] not only fame and fortune, but also respectability" (11) is emphasized, stressing the illustrator's quintessentially Victorian quest for recognition at a time when artistic masculinity, influenced by Evangelicalism and now adjusted to the pursuits of a largely commercial middle class, was increasingly constructed around the notions of effort and self-discipline.

Devoted to “Political Culture in the Later Nineteenth Century,” the second chapter insightfully documents the changing relationship between politics and the Victorian public. Identifying the 1867-68 broadening of the franchise as the main source of a need for British politicians to communicate with an extended electorate, Humours of Parliament insists on "the creation of a politics of personality that relied on various forms of performative appeal," seeing in Furniss's lecture-entertainment the expression of a "platform culture in which speech-making, performance, and politics were [...] closely linked" (26-27). At a time which saw the birth of "a sophisticated consumer culture in which public figures are marketed as commodities to be circulated and consumed" (34), the repeated performances of "The Humours of Parliament," Meisel and Cordery contend, played a decisive role in the cultivation and circulation of recognizable public figures. Simultaneously, Furniss's magic lantern show was instrumental in the political education of an electorate now including significant portions of artisans and urban labourers. Refusing to establish a clear distinction between education and entertainment (47), "The Humours" "demystified Parliament, personalized its members, and educated the audience on its procedures, so important in the new era of mass democracy" (50).

Left to right: (a) "My Caricature of Mr Gladstone," with the turned-up collar which Furniss invented for him, as shown also on Cordery and Meisil's book-cover (Furniss I: frontispiece). (b) Another of the "Grand Old Men" of Victorian politics seen through Furniss's eyes — a serious sketch of the portly Third Marquess of Salisbury (1830-1903) making a point in the House of Lords (1891). (c) A poster for a performance of "The Humours of Parliament" in Scotland, partly inspired by the parliamentary scenes shown above (with thanks to the University of Exeter's Digital Collection Online).

But beyond its general educational interest, "The Humours" also drew its inspiration from topical events and figures. Entitled "Furniss and the Politics of the 1880s and 1890s," the next chapter identifies in "The Grand Old Man," "Women" and "Ireland and the Home Rule" the three main points of interest Furniss's lecture hinges around. However, "the attention [Furniss] does pay to the Irish and to women," the editors remark, "may have less to do with reflecting political trends, and more to do with his own personal interest in both, the material available among the body of his drawings, and the kind of comedy (both visual and spoken) that each group afforded within the conventions of the times" (64). Hence, perhaps, the absence of any mention of the working class or their representatives in Parliament whom, the editors argue, Furniss had no interest in, and even scorned.

The technical aspects of the lecture-entertainment are thoroughly tackled in the next chapter, which closely examines "The Creation and Performances of 'Humours.'" The wide popularity of the magic lantern throughout the late Victorian period is here analyzed as one of the reasons accounting for the success of a show also meant to counter the "relentless cheerlessness [...] which increasingly characterized the world of the fin-de-siècle illustrated lecture" (71) Cordery and Meisel's serious and documented study also encompasses the actual working of the lantern itself as well as the sometimes erratic way in which Furniss related text and image. "While the extant manuscript gives cues for 104 slides," the editors explain, "160 was the figure noted in two accounts from 1891" (75) Appendix II (275) bridges this gap by listing the images reported as shown in "Humours" but not cued in Furniss's text.

Another interesting point tackled here concerns the nature of Furniss's audiences as he toured most British cities. Relying on various contemporary sources including Furniss's writings and the local press which the informative footnotes often refer to, Cordery and Meisel manage to establish a cross section of the artist's public as he traveled across the country. Posters and advertisements are another source of information allowing the editors to recreate the ticket pricing scheme of the shows in many venues in England and thus to make inferences about audience composition. From "small but select" (104) to "the most recently enfranchized segments of the electorate" (107), the public of "Humours" seems to have encompassed a significantly wide spectrum of the middle classes.

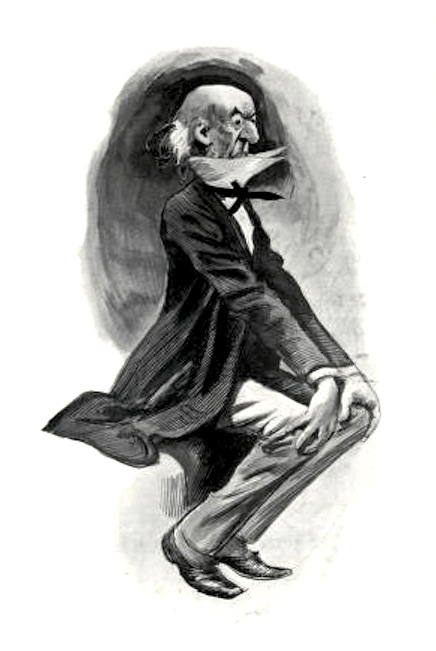

Left: Frontispiece to T.H. McAllister's Catalogue, published in New York in 1887. Furniss's reception in America is reported to have been "generally positive" (118), if not quite as rewarding as he might have wished. Right: "Harry Furniss as a Pictorial Entertainer," drawn by Clement Flower (1900), in Furniss II, 182.

The last thematic chapter of this comprehensive introduction concerns the purpose and unfolding of the North American and Australian circuits. One of the interesting concepts developed by Cordery and Meisel in this part is the role played by the show in the construction of Englishness abroad and more precisely in the diffusion of the British parliamentary model:

Westminster, too, had its trappings [...] but either directly or indirectly the British legislature (as the "mother of parliaments") served as a model for emerging democracies around the world, not least in settler colonies like Australia in which the development of responsible self-government had been advancing for some decades. [125]

Cordery and Meisel's scholarly editorial approach is made explicit in Chapter VI, in which the limited accessibility of primary sources as well as the palimpsestic dimension of the lecture itself are underlined. Insisting on "what is most significant for political and cultural historians" rather than on an "idealized text and set of images" (135), the editors reiterate their wish to offer their readers the opportunity "to appreciate this material from multiple perspectives."

Copiously annotated, the text of "The Humours" is then presented and examined "as a living evolving production" (138). Throughout the 120-page-long extant text of "The Humours," Cordery and Meisel have managed to retain the spirit of Furniss's sometimes meandering and digressive magic lantern show while providing the readers with enlightening information in their numerous and well-researched footnotes. The focus is here however on the text rather than on the images. More scope could perhaps have been given to the pictorial conventions at work in Furniss's vignettes. As Mary Cowling has documented in The Artist as Anthropologist (1989), the male body, as represented by Victorian painters, illustrators and caricaturists, may be read as a discourse on propriety which, albeit mentioned here, could have been made more vivid through the variety of illustrations shown as part of the performance. The role of visual representations as a means of constructing opinions is also mentioned by Tim Barringer who, in "Images of Otherness," stresses their "active and formative role in cultural discourses, notably that of race" (35). This very slight drawback does not, however, lessen the quality of this informative and extremely well-researched volume which provides a decisive contribution to the field of nineteenth-century cultural studies, shedding useful (lime)light on Victorian platform culture and stressing the role of such performances in the construction of Englishness.

Related Material

- Essence of Parliament: Rehearsal for Opening Day

- Essence of Parliament: Increased facilities are provided for Ladies dining, &c., with Members

- Harry Furniss's Gladstone: Reflections on the Caricaturist's Art

Bibliography

[Book under review:] Cordery, Gareth, and Joseph S. Meisel, eds. The Humours of Parliament: Harry Furniss's View of Late-Victorian Culture. Columbus: The Ohio State University Press, 2014. Hardback. xxii+320 pages. ISBN 978-0814212530. $89.95

Barringer, Tim. "Images of Otherness and the Visual production of Difference: Race and Labour in Illustrated Texts." In Shearer West, ed. The Victorians and Race. Aldershot: Scolar Press, 1996: 34-52.

[Illustration sources:] Catalogue and price list of stereopticons, dissolving view apparatus, magic lanterns, and artistically-colored photographic views on glass, for T. H. McAllister. New York, 1887. Internet Archive. Contributed by the Winterthur Museum Library. Web. 20 April 2015.

Furniss, Harry. The Confessions of a Caricaturist. Vol. I. Toronto: William Briggs, 1902. Internet Archive. Contributed by Robarts Library, University of Toronto. Web. 20 April 2015.

_____. The Confessions of a Caricaturist. Vol. II. Toronto: William Briggs, 1902. Internet Archive. Contributed by Robarts Library, University of Toronto. Web. 20 April 2015.

Created 20 April 2015

Last modified 7 February 2020