‘Chris’ Hammond (1860–1900) was one of the most productive illustrators of the 1890s. Best known as an interpreter of classic fiction, she embellished texts by Jane Austen, Maria Edgeworth, W. M. Thackeray, George Eliot and a number of others, as well as contributing to Cassell’s Magazine, The Quiver, and St Pauls. Her books, several of which are bound in casings by A. A. Turbayne and Talwin Morris, command high prices, and are keenly collected. She was also a painter, exhibiting eighteen genre pieces at the Royal Academy, The Royal Institute of Painters in Watercolour, the Grosvenor Galleries and in the galleries in Suffolk Street.

Hammond worked in the Regency idiom popularized by Hugh Thomson and Charles Brock, and her illustrations in pen and ink are comparable with their designs. Yet, though admired, her art has never been the subject of detailed analysis. She is listed in the standard reference books, but absent from discussions of the period. This is surprising, given her unusual position as a woman artist at work within a predominantly male profession. Active in the same period as Kate Greenaway, Beatrix Potter and Mary Ellen Edwards, she deserves to take her place next to them.

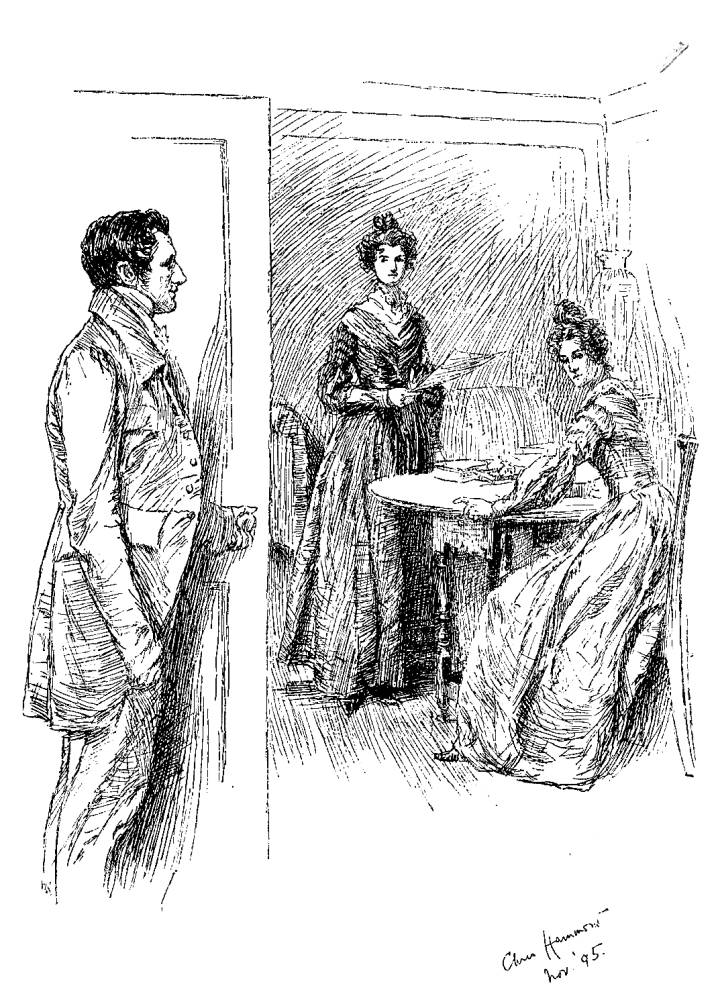

Three illustrations by Hammond: Left: As they blazed. Middle: Reading. Right: Elisa. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Life and Work

Sometimes known as Christine and always as Chris, Christiana Mary Demain Hammond was born in June 1860 in the parish of St Giles, Camberwell, London, the first of three children. Her background was lower middle-class; her father was a banker’s clerk, and the address suggests a modest income. The Hammonds were nevertheless a remarkable family, with all of the siblings distinguishing themselves as artists. Chris was the most successful, but her sister Gertrude trained as a painter and her brother, Percy Edward, became a designer of paintings on stained glass.

Chris trained at the Lambeth School of Art; the Census records her status in 1881 as one of an ‘art student’, and it is likely that she attended (in the company of her sister) for several years. Though associated with Doulton pottery and a source of painters who embellished porcelain and fine ceramics (Gillett, p. 167), by the time of the sisters’ attendance the School was also teaching more general classes in life drawing and modelling, a near equivalence to the studies offered to men at institutions such as Heatherley’s. The fees were considerable and must have been paid by Chris’s father, a development which suggests an improvement in the family’s income.

This training in draughtsmanship and especially figure drawing was the prime constituent in Hammond’s education, although completion of her studies was by no means a guarantee of employment. As Paula Gillett explains in her analysis of Victorian women artists:

Most of the women who studied fine art [in the final decades of the century] did so with little realistic hope of establishing self-supporting careers, although many held vaguely formulated ideas of becoming professional artists, either until or (if need be) instead of marriage [p. 167].

However, Hammond was not constrained by these limiting circumstances. She quickly progressed to exhibiting work at the Royal Academy (1886) and The Royal Institute of Painters in Watercolours (1886) while also (in all likelihood) producing work for commissions. Unlike Mary Ellen Edwards and many others who supported an artistic career with the financial assistance of a husband while dealing with the domestic arrangements of having children and running a household, Hammond never married and proceeded purely on the basis of her own labour; sharing accommodation with her sister, she was a jobbing professional who worked for herself and was in many ways the epitome of the ‘New Woman’ of the end of the century.

Three illustrations by Hammond: Left: “I must see you”. Middle: She turned away. Right: Mr Beauclere. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

It was not until the nineties, however, that she found a series of positions that enabled her to establish herself in the public eye and gain greater economic security. She contributed a number of illustrations to Pall Mall Magazine (1891–2), The Quiver (1894–5), Pearson’s Magazine (1896) and The Idler (1892). In 1894 she became the principal illustrator for St Pauls Magazine, and during the years from 1895 to 1900 she illustrated the elaborate editions of Austen, Goldsmith, Thackeray, Richardson and Edgeworth that became her signature work.

Hammond died unexpectedly in her studio at the premises of St Pauls Magazine on 15 May 1900; she was 39 years of age, and the cause of death unknown. She was buried in Norwood Cemetery, London. Remembered by an obituary in The Argosy in July 1900, her reputation immediately declined.

Style and Idiom

‘Hammond drew in the idiom that is often described as the ‘Cranford style’ which first appeared in Macmillan’s celebrated edition of 1891. Apart from herself, its main practitioners were Hugh Thomson, Charles and Henry Brock and F. W. Townsend; Kate Greenaway and Randolph Caldecott worked in the same vein. There was no contact between the artists, who were linked purely on the basis of being fellow practitioners in a style which celebrated a sentimental, pre-industrial notion of ‘old England’. This involved the careful representation of Regency dress and interiors, pastoral settings and sharp characterization which was based on a close reading of the text.

Hammond’s contribution to this escapist discourse was simple but effective. Though representing her characters with historical exactitude, her main focus is on small nuances of facial expression and gesture. This capacity makes her an ideal illustrator for Jane Austen; she illustrated Sense and Sensibility(1899) and Emma (1898), in both cases representing the main characters in ways that stress their individuality. Varying postures, gestures and expressions are elements in this language, and Hammond’s terse line often creates a spontaneous, and sometime even a febrile effect. She notably foregrounds the texts’ drama; most of the scenes are encounters in which key information is exchanged. The action is further animated by doors opening in the background, with others straining to hear; though composed as tableaux, the illustrations often deploy diagonal arrangements and steep recessions which stress movement and suggest the characters’ changing state of mind. Working within an idiom that is essentially decorative rather than interpretive, Hammond conveys other levels of meaning which, in the manner of all meaningful illustration, enhances the reader’s understanding.

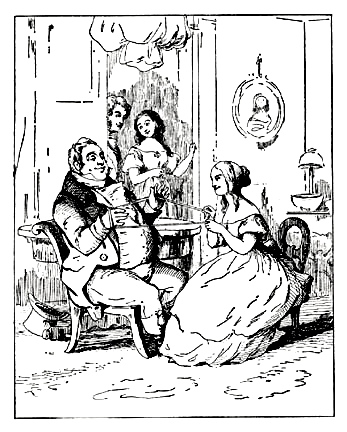

Two of Christiana Hammond’s illustrations of Thackeray’s Vanity Fair compared to one by Thackeray himself. Left: Bound in a web of green silk. Middle: . Right: Mr. Joseph entangled by W. M. Thackeray. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Her most accomplished work features in her version of Thackeray’s Vanity Fair (1898). Though issued by Service and Paton, a minor late Victorian publisher, and printed on poor quality paper, Hammond’s designs lift the production. Her characterization of Becky Sharp as a ‘minx’ is conveyed in her portraiture, which stresses her sharp features and knowing gaze, and Jos and Dobbin are similarly presented as tangible individuals rather than types; each bears interesting comparison with Thackeray’s cartoon-like originals.

Taken as a whole, Chris Hammond made a small but significant contribution to book design of the final decade of the nineteenth century. If Aubrey Beardsley and Laurence Housman were the champions of the avant-garde, Hammond was the epitome of conservative taste. Catering for a large bourgeois audience, her refined and perceptive illustrations had a wide currency, only supplanted by the growing taste for the radicalism of English Art Nouveau.

Works Cited

Ancestry.co.uk. Web. 9 April 2016.

Gillett, Paula. The Victorian Painter’s World. Gloucester: Sutton, 1990.

Houfe, Simon. The Dictionary of Nineteenth Century British Book Illustrators.(Woodbridge: The Antique Collectors’ Club, 1978; revd ed., 1996.

Books Illustrated by Chris Hammond: a Select List

Austen, Jane. Emma.London: Allen, 1898.

Austen, Jane. Sense and Sensibility.London: Allen, 1899.

Blackmore, R.D. Daniel.London: Macmillan, 1897.

Edgeworth, Maria. Castle Rackrent.London: Macmillan, 1895.

Edgeworth, Maria. Helen.London: Macmillan, 1896.

Gaskell, Elizabeth. Cranford.London: Gresham [1900].

Goldsmith, Oliver. Comedies.London: Allen, 1898.

Thackeray, W. M. Vanity Fair. London: Service & Paton, 1898.

Last modified 9 April 2016