rthur Boyd Houghton excelled in the representation of children, and it is widely assumed that his approach to the subject is sentimental in the manner, say, of Robert Barnes. Once again, it is the Dalziels who present the most interesting testimony. According to the Brothers, ‘One of his characteristics was his great love of children. It was a pleasure to him to get a party of young people together, and go off to the fields to romp and play all sorts of games and antics’ (p.222).

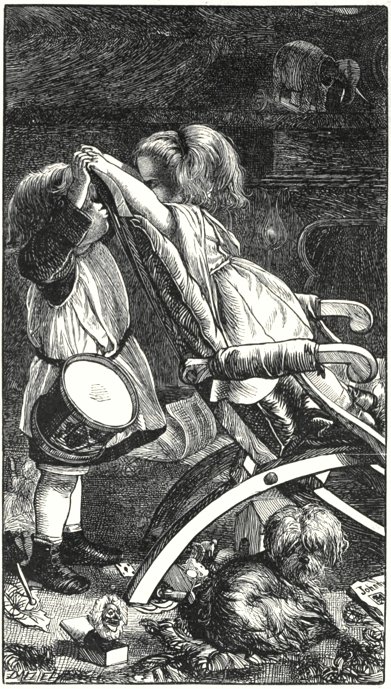

Arthur Boyd Houghton's My Treasure and Childhood.

[Click on images to enlarge them.]

This judgement seems partly justified by Houghton’s engravings in Good Words, 1862–3. Illustrations such as My Treasure and Childhood are unashamedly and almost cloyingly sentimental. Childhood, especially, is a fancy confection of plump middle-class infants, a cute dog and quaint toys; faux-naif in effect, it calculatedly presents a stereotypical construction of childhood as a domain of innocence. This is nevertheless only one aspect of the artist’s treatment of juveniles. His approach to childhood is more characteristically the very reverse of sentimentality: the Dalziels may have believed him to be appreciative of the young, but in practice most of his illustrations are explorations of childhood suffering and anguish in which children are shown as anything but innocent or guileless. Indeed, his images of children, so Goldman tells us, are ‘some of the most dark and disturbing’ in ‘all illustration’ (Victorian Illustration, p.126). This approach is exemplified by Home Thoughts and Home Scenes (1865).

Home Thoughts contains a series of bold full-page wood-engravings which illustrate poems by Jennett Humphreys, Dora Greenwell, Jean Ingelow and a number of other female writers. The verse is conventional and anodyne in the manner of the mid-Victorian gift book, but several of Houghton’s designs add another, and contradictory, element in which the blandness of the writing is matched by curious representations of disorder and fear. While some of the illustrations are sentimental and match the tone of at least a number of the poems, the images are generally at odds with their literary source-material, and critics have viewed the book as a vehicle for the illustrator’s own purposes. What these purposes were is not easy to determine.

Lorraine Janzen Kooistra has argued that Houghton’s images of children at play are representations of the roles that will be expected of them in adulthood, so providing a sort of symbolic reflection on adult, rather than juvenile experience. As Kooistra explains, the ‘iconic pictures … deploy the domestic as the site where middle-class children rehearse their future roles on the adult stage as bourgeois capitalists, national defenders and moral and spiritual exemplars’ of appropriate behaviour (p.173). The struggles depicted in the illustrations become in this sense a lightly-coded depiction of what Dickens defines as ‘the Battle of Life’, and intersects with Darwinian notions (1859) of the struggle to live.

The illustrations might also be read, as I recently argued (2012), as a satirical commentary on mid-Victorian ideas of parenting and how best to rear a child. According to this argument, Houghton’s images of struggle and discord are best understood as a hit on parental incompetence and on the absurdities of contemporary theory. Houghton, I suggest:

focuses on contemporary ideas of [childish] self-expression, which, contrary to modern understandings of Victorian parenting, and in absolute contradiction of the Dickensian model of familial abuse and cruelty, stressed the value of allowing the young to do whatever they wanted. Indeed, Home Thoughts can be viewed as a critical response to the idea of ‘active playfulness’, the notion, as expressed in numerous domestic primers, that parents, especially mothers, should not impose a repressive regime but encourage their child to ‘shout and riot and romp about as much as he pleases’ [p.72].

Read either way, or as a combination of both arguments, Home Thoughts presents a notion of childhood that is far from idealised or sentimental. Rarely at ease, children are shown in tears (p.7), calling out (p.12) or sullenly withdrawn (p.20). Engaged in a version of play based on fighting, the images depict struggles on the floor, the emptying of drawers and sideboards, the breaking of toys and the deployment of mock-weapons. This imagery has a sense of personal investment, and it is interesting to reflect that the artist lost one of his eyes, aged five or six, in when a play-mate fired a toy cannon into his face.

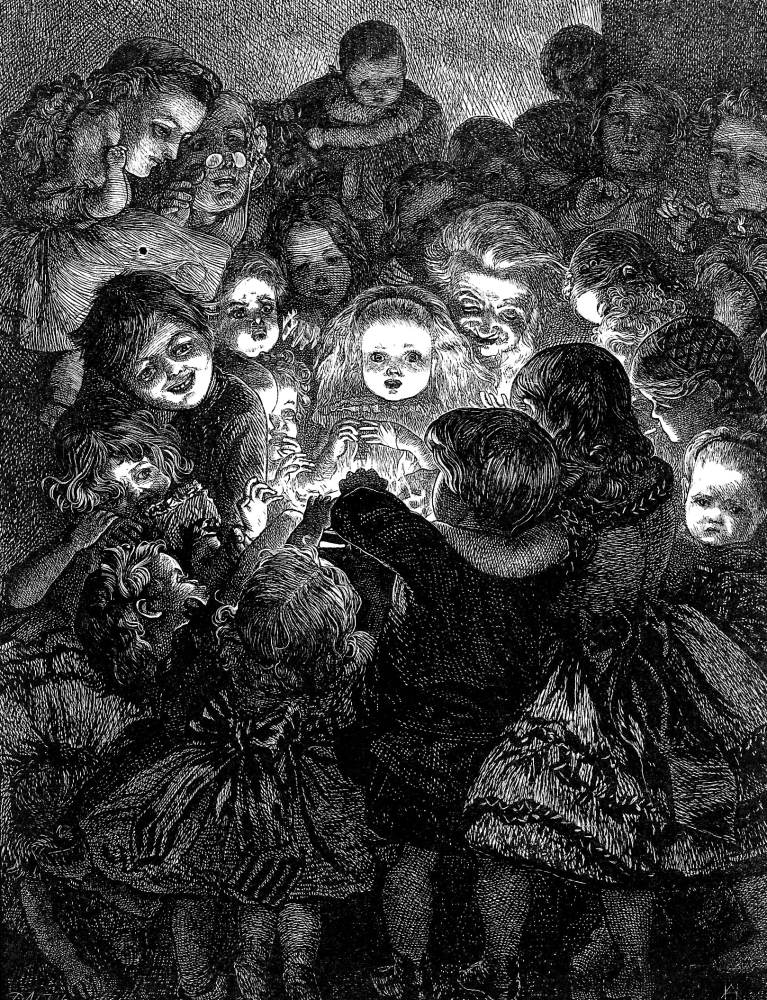

Arthur Boyd Houghton's Snapdragon and A Story by the Fireside. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Such fearfulness pervades the designs, and sickness, jealousy, death, disability, anxiety and anguish are the their signature emotions; there is little sense of repose or simple contentment, and the unsettling effect is further heightened by Houghton’s use of mask-like faces and menacing darkness. Most disturbing, perhaps, is Snapdragon. This represents a contemporary game in which children compete with each other to grab fruit out of a flame. To modern taste the idea is itself horrifying, and Houghton unambiguously showing the participants as fearful and unsure. These emotions are signalled in the form of distorted faces that emerge from a shimmering chiaroscuro, eerily anticipating the expressionist effects of James Ensor and Emile Noldë; Goya is also invoked.

Complex and frightening, Home Thoughts seems a curious type of gift book, and it is hard to know its audience and to whom it would appeal. Goldman notes its representation of Home as a site of ‘deep unease’ (Chidren’s Illustration, p.12), and the book did not fit easily into its genre. Many contemporaries identified the uncertainty of the pitch, commenting how it depicted ‘fun’ (of a sort), but was undoubtedly ‘peculiar’ (Art Journal, 1865: p.376). The adjective is a telling one.

Related Material

- Arthur Boyd Houghton as a stylist: from the Orient to images of the Victorian poor

- Houghton, escapism, and contemporary life

Related Material

- Arthur Boyd Houghton as a stylist: from the Orient to images of the Victorian poor

- Houghton, escapism, and contemporary life

Last modified 19 August 2013