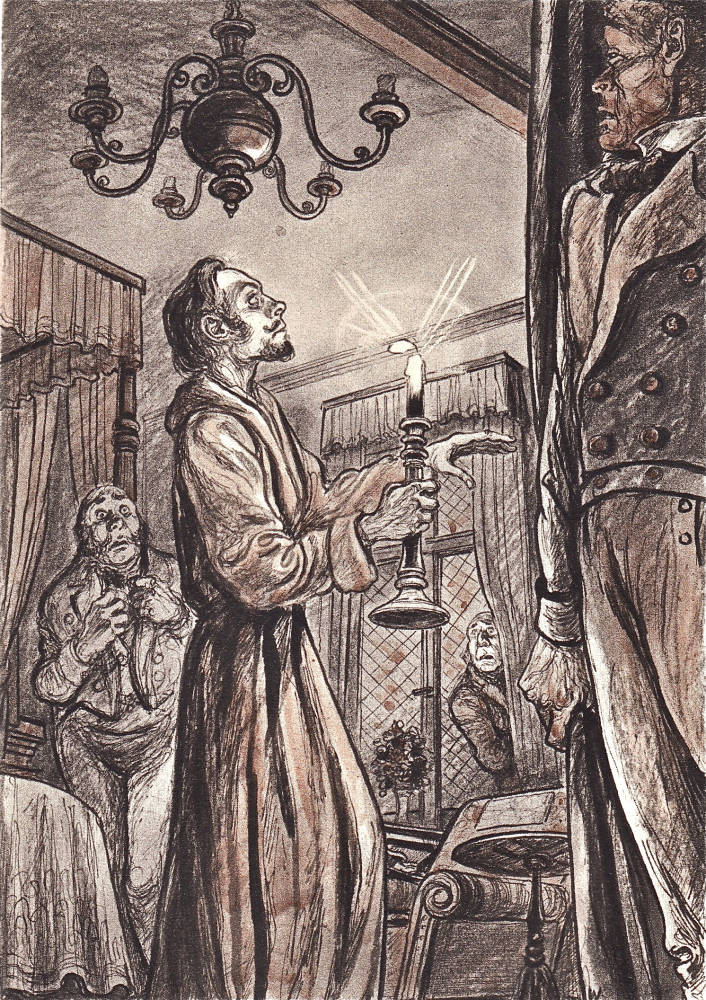

[Franklin Blake, carrying a guttering candle that suggests rapid walking down the corridor in the Verinder country-house] — Wilkie Collins's The Moonstone: A Romance: "Second Period, Fourth Narrative, Extracted from the Journal of Ezra Jennings," uncaptioned headnote vignette, the twenty-fifth such vignette. The thirtieth instalment in Harper's Weekly (25 July 1868), page 469. Wood-engraving, 8.9 x 5.4 cm., located towards the end of Jennings' journal account of the laudanum experiment in the initial volume edition, p. 205. [The generalised physical setting turns out to be the corridor just outside Franklin Blake's assigned bedroom in the Verinder country-house as under the influence of the drug he retraces his steps of the previous year.]

Scanned images and text by Philip V. Allingham. Illustrations courtesy of the E. J. Pratt Fine Arts Library, University of Toronto, and the Irving K. Barber Learning Centre, University of British Columbia. [You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the Universities of Toronto and British Columbia and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite The Victorian Web in a print one.]

Passage suggested by the Headnote Vignette for the Thirtieth Instalment

He laid himself down again on the bed!

A horrible doubt crossed my mind. Was it possible that the sedative action of the opium was making itself felt already? It was not in my experience that it should do this. But what is experience, where opium is concerned? There are probably no two men in existence on whom the drug acts in exactly the same manner. Was some constitutional peculiarity in him, feeling the influence in some new way? Were we to fail on the very brink of success?

No! He got up again abruptly. "How the devil am I to sleep," he said, "with thison my mind?"

He looked at the light, burning on the table at the head of his bed. After a moment, he took the candle in his hand.

I blew out the second candle, burning behind the closed curtains. I drew back, with Mr. Bruff and Betteredge, into the farthest corner by the bed. I signed to them to be silent, as if their lives had depended on it.

We waited — seeing and hearing nothing. We waited, hidden from him by the curtains.

The light which he was holding on the other side of us moved suddenly. The next moment he passed us, swift and noiseless, with the candle in his hand.

He opened the bedroom door, and went out.

We followed him along the corridor. We followed him down the stairs. We followed him along the second corridor. He never looked back; he never hesitated.

He opened the sitting-room door, and went in, leaving it open behind him. — "Fourth Narrative, extracted from the Journal of Ezra Jennings,"p. 470.

Commentary

The Harper'sillustrators also repeatedly deploy threshold settings, locating Collins's characters near doors or windows. These thresholds, we argue, visually suggest the sensation genre’s propensity for disrupting boundaries of gender and class, as well as this particular novel's violation of barriers between the known and the unknown, white and nonwhite, England and its foreign others, law and desire, the conscious and the unconscious. The illustrations show Rachel watching the man she loves steal her gemstone (chapter head, Part 25); Rachel watching the investigation and wishing that Franklin might escape (Part 6, fig. 7); and Franklin sleepwalking, midway between conscious and unconscious states (chapter head, Part 30). All of these events place characters in positions where their conscious ethics and their basic drives collide, suggesting how the novel presses beyond the surface of identity, probing its margins. The illustrations contribute, then, to the novel's status as sensation fiction, suggesting the text's roiling undercurrents, its deep-set fears of colonial invasion at the heart of England, and its capacity to undermine or cross boundaries fundamental to self and social identities.— Surridge and Leighton, p. 222.

The serial instalment for 25 July 1868 uses the headnote vignette to describe Franklin Blake's sleepwalking under the influence of the slightly enlarged dose of laudanum administered by Ezra Jennings, but does not show his opening the cabinet to move the Moonstone. Whereas Blake in the British illustrations is wearing a linen nightgown, in the American illustration, as he walks down the corridor, he is wearing a dressing-gown and (apparently) pyjamas, perhaps signifying transatlantic differences in men's sleepwear — and perhaps underscoring the American illustrators' disregarding textual details to make the illustration conform to their readers' expectations. The two illustrations for July 25 (rather than the customary three) contain a gap or ellipsis, and are arrayed in reverse chronological order. In other words, the illustrators show the result of Blake's taking the drug before they show the group mixing the drug in proper proportions in water, leaving the reader to fill in the blank, the critical scene in which Blake opens the cabinet and takes the Diamond. Thus, the illustrations complement the text but do not pre-empt it, compelling readers to find out for themselves (and to picture in the mind's eye) the highly dramatic scene in Rachel's sitting-room that ends the thirtieth instalment. Moreover, whereas the serial had yet to reveal three significant illustrations in the remaining pair of instalments, the picture of Franklin Blake before the Indian cabinet effectively closes both British narrative-pictorial sequences, leaving the English reader to conclude that Collins manages to achieve a happy ending, at least for Franklin Blake and Rachel Verinder.

Relevant Chatto and Windus Edition (1890) and Collins Clear-type Edition (1910) Illustrations

Left: F. A. Fraser's realisation of Franklin Blake's taking the substitute Moonstone under the influence of laudanum, "He took the mock Diamond out with his right hand." (1890). Centre: Alfred Rearse's recapitulation of the 1890 illustration, "He took the Diamond." (1910). Right: William Sharp's illustration of the reconstructed crime-scene, Franklin Blake sleepwalking (uncaptioned, 1944). [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Related Materials

- The Moonstone and British India (1857, 1868, and 1876)

- Detection and Disruption inside and outside the 'quiet English home' in The Moonstone

- Illustrations by F. A. Fraser for Wilkie Collins's The Moonstone: A Romance (1890)

- Illustrations by John Sloan for Wilkie Collins's The Moonstone: A Romance (1908)

- Illustrations by Alfred Pearse for The Moonstone: A Romance (1910)

- The 1944 illustrations by William Sharp for The Moonstone (1946).

Last updated 1 December 2016