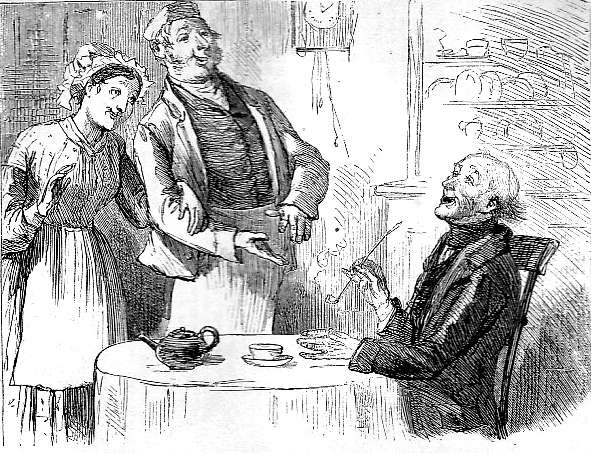

They were within five minutes of their destination. (See page 189), — Book I, chap. 31, Sixties' illustrator James Mahoney's twenty-seventh illustration in the Chapman and Hall Household Edition volume of Charles Dickens's Little Dorrit, 1873. Wood-engraving by the Dalziels, 9.3 cm high by 13.8 cm wide, framed. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL.]

Passage Illustrated

They walked at a slow pace, and Little Dorrit took him by the Iron Bridge and sat him down there for a rest, and they looked over at the water and talked about the shipping, and the old man mentioned what he would do if he had a ship full of gold coming home to him (his plan was to take a noble lodging for the Plornishes and himself at a Tea Gardens, and live there all the rest of their lives, attended on by the waiter), and it was a special birthday of the old man. They were within five minutes of their destination, when, at the corner of her own street, they came upon Fanny in her new bonnet bound for the same port.

"Why, good gracious me, Amy!" cried that young lady starting. "You never mean it!"

"Mean what, Fanny dear?"

"Well! I could have believed a great deal of you," returned the young lady with burning indignation, "but I don't think even I could have believed this, of even you!"

"Fanny!" cried Little Dorrit, wounded and astonished.

"Oh! Don't Fanny me, you mean little thing, don't! The idea of coming along the open streets, in the broad light of day, with a Pauper!" (firing off the last word as if it were a ball from an air-gun).

"O Fanny!"

I tell you not to Fanny me, for I'll not submit to it! I never knew such a thing. The way in which you are resolved and determined to disgrace us, on all occasions, is really infamous. You bad little thing!"

Does it disgrace anybody," said Little Dorrit, very gently, to take care of this poor old man?"

"Yes, miss," returned her sister, "and you ought to know it does. And you do know it does, and you do it because you know it does. The principal pleasure of your life is to remind your family of their misfortunes. And the next great pleasure of your existence is to keep low company. But, however, if you have no sense of decency, I have. You'll please to allow me to go on the other side of the way, unmolested."

With this, she bounced across to the opposite pavement. The old disgrace, who had been deferentially bowing a pace or two off (for Little Dorrit had let his arm go in her wonder, when Fanny began), and who had been hustled and cursed by impatient passengers for stopping the way, rejoined his companion, rather giddy, and said, "I hope nothing's wrong with your honoured father, Miss? I hope there's nothing the matter in the honoured family?"

"No, no," returned Little Dorrit. "No, thank you. Give me your arm again, Mr. Nandy. We shall soon be there now." — Book the First, "Poverty," Chapter 31, "Spirit," p. — Book the First, "Poverty," Chapter 31, "Spirit," p. 189.

Commentary

The half-page illustration occurs within p. 185 of the thirtieth chapter of Book One, "Poverty," with the running head Some Secrets in All Families — here, somewhat ironic in that the Plornishes do not attempt to disguise the fact that Nandy is a resident of the Union Workhouse. This is a somewhat lacklustre response to the more lively group study in the 1856-57 serial, The Pensioner Entertainment, in which the Father of the Marshalsea outrageously (and hilariously) patronizes Old Nandy as a decrepit "Pauper." Mahoney does not duplicate the work of Dickens's original illustrator, "Phiz" (Hablot Knight Browne), but rather complements Phiz's realisation of the subsequent scene of pointless snobbery and foolish class-consciousness at the Marshalsea rooms of William Dorrit (Part 9: August 1856). The Household Edition illustration, proleptically situated four pages ahead of the passage realised, shows a downcast Amy, genuinely sorry to think that she has somehow offended her younger sister in her new bonnet (upper left, back to the reader and to Amy), round the corner rather than across the street, as in the text. Ever the model of Victorian middle-class femininity — charity, kindness, self-sacrifice, and dutifulness, Amy Dorrit supports the doddering Old Nandy, the aged music-binder who, like William Dorrit, fell into debt years before, but chose to commit himself to the Union Workhouse rather than be arrested for debt. Whereas Phiz's realisation of Old Nandy conveys well his perpetually cheerful nature, as opposed to William Dorrit's puffery and discontent, Mahoney's shows him as well-dressed but pathetically frail:

Mrs. Plornish's father, — a poor little reedy piping old gentleman, like a worn-out bird; who had been in what he called the music- binding business, and met with great misfortunes, and who had seldom been able to make his way, or to see it or to pay it, or to do anything at all with it but find it no thoroughfare, — had retired of his own accord to the Workhouse which was appointed by law to be the Good Samaritan of his district (without the twopence, which was bad political economy), on the settlement of that execution which had carried Mr Plornish to the Marshalsea College. Previous to his son-in-law's difficulties coming to that head, Old Nandy (he was always so called in his legal Retreat, but he was Old Mr Nandy among the Bleeding Hearts) had sat in a corner of the Plornish fireside, and taken his bite and sup out of the Plornish cupboard. He still hoped to resume that domestic position when Fortune should smile upon his son-in-law; in the meantime, while she preserved an immovable countenance, he was, and resolved to remain, one of these little old men in a grove of little old men with a community of flavour.

But no poverty in him, and no coat on him that never was the mode, and no Old Men's Ward for his dwelling-place, could quench his daughter's admiration. — Book the First, "Poverty," Chapter 31, "Spirit," p. 187.

Related Illustrations, 1867-1910: The Diamond, Household, and Charles Dickens Library Editions

Left: Harry Furniss's interpretation of the Fanny Dorrit's accusing her sister, Amy, of having "lowered" herself by having been seen in public with a "Pauper," Little Dorrit disgraces her family (1910). Right: Sol Eytinge, Junior's study of the jolly Plornishes of Bleeding Heart Yard, Mr. and Mrs. Plornish and John Edward Nandy. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Above: Phiz's original illustration of the Dorrits' dinner in the Marshalsea, The Pensioner Entertainment (August 1856). [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

References

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by Hablot Knight Browne ("Phiz"). The Authentic Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1901 [rpt. of the 1868 volume, based on the 30 May 1857 volume].

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Frontispieces by Felix Octavius Carr Darley and Sir John Gilbert. The Household Edition. 55 vols. New York: Sheldon & Co., 1863. 4 vols.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1867. 14 vols.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by James Mahoney. The Household Edition. 22 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1873. Vol. 5.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book, 1910. Vol. 12.

Hammerton, J. A. "Chapter 19: Little Dorrit." The Dickens Picture-Book. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. 18 vols. London: Educational Book Co., 1910. Vol. 17. Pp. 398-427.

Harvey, John. Victorian Novelists and their Illustrators. London: Sidgwick and Jackson, 1970.

Kitton, Frederic George. Dickens and His Illustrators: Cruikshank, Seymour, Buss, "Phiz," Cattermole, Leech, Doyle, Stanfield, Maclise, Tenniel, Frank Stone, Landseer, Palmer, Topham, Marcus Stone, and Luke Fildes. Amsterdam: S. Emmering, 1972. Re-print of the London 1899 edition.

Lester, Valerie Browne. Phiz: The Man Who Drew Dickens. London: Chatto and Windus, 2004.

"Little Dorrit — Fifty-eight Illustrations by James Mahoney." Scenes and Characters from the Works of Charles Dickens, Being Eight Hundred and Sixty-six Drawings by Fred Barnard, Gordon Thomson, Hablot Knight Browne (Phiz), J. McL. Ralston, J. Mahoney, H. French, Charles Green, E. G. Dalziel, A. B. Frost, F. A. Fraser, and Sir Luke Fildes. London: Chapman and Hall, 1907.

Matz, B. W., and Kate Perugini. Character Sketches from Dickens. Illustrated by Harrold Copping. London: Raphael Tuck, 1924.

Steig, Michael. Dickens and Phiz. Bloomington & London: Indiana U.P., 1978.

Vann, J. Don. Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: The Modern Language Association, 1985.

Last modified 12 May 2016