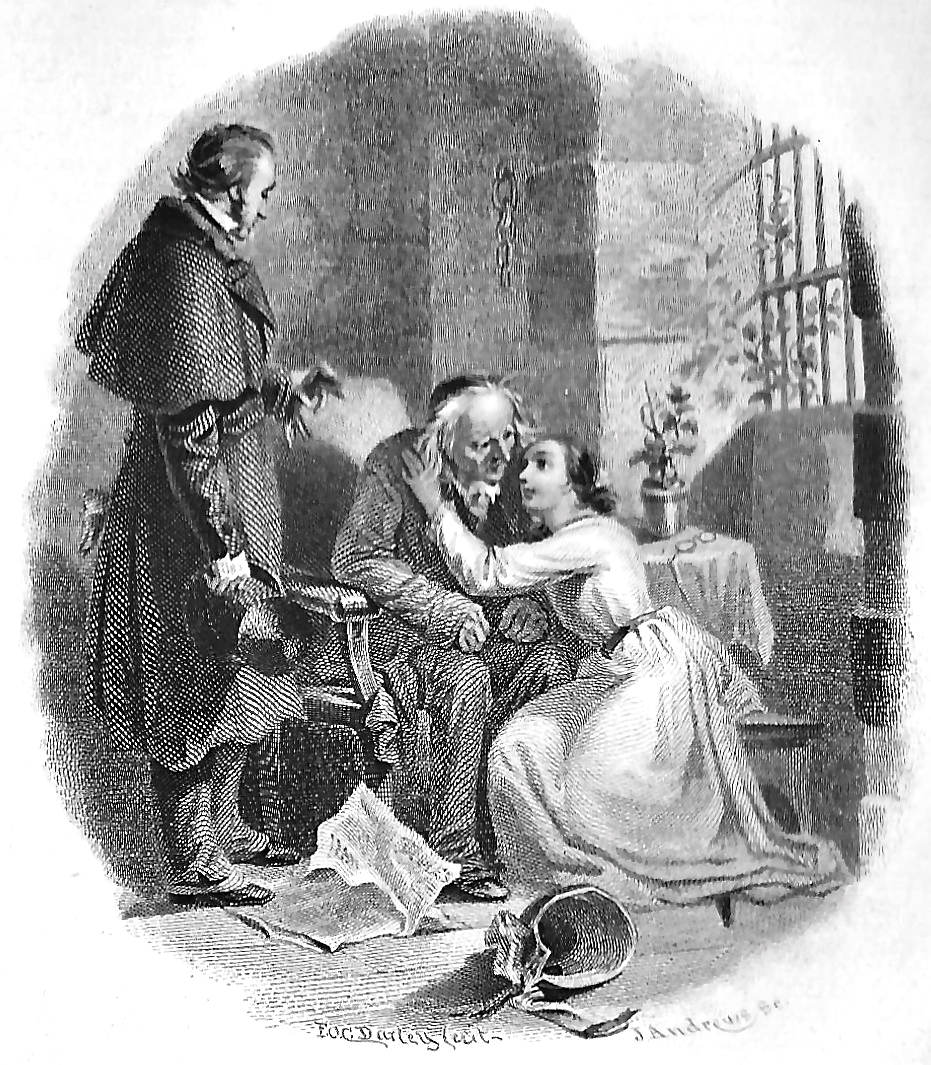

Clennam rose softly, opened and closed the door without a sound (See page 216), — Book I, chap. 35, is the full title as given in the Chapman and Hall printing. Sixties' illustrator James Mahoney's twenty-ninth illustration for Charles Dickens's Little Dorrit, Household Edition, 1873. Wood-engraving by the Dalziels, 10.5 cm high by 13.5 cm wide, p. 209, framed, under the running head "High Company." [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL.]

Passage Illustrated

The prison, which could spoil so many things, had tainted Little Dorrit's mind no more than this. Engendered as the confusion was, in compassion for the poor prisoner, her father, it was the first speck Clennam had ever seen, it was the last speck Clennam ever saw, of the prison atmosphere upon her.

He thought this, and forbore to say another word. With the thought, her purity and goodness came before him in their brightest light. The little spot made them the more beautiful.

Worn out with her own emotions, and yielding to the silence of the room, her hand slowly slackened and failed in its fanning movement, and her head dropped down on the pillow at her father's side. Clennam rose softly, opened and closed the door without a sound, and passed from the prison, carrying the quiet with him into the turbulent streets. — Book the First, "Poverty," Chapter 35, "What Was Behind Mr. Pancks on Little Dorrit's Hand," p. 216.

Commentary

The title is somewhat longer in the New York (Harper and Brothers) printing: Worn out with her own emotions, and yielding to the silence of the room, her hand slowly slackened and failed in its fanning movement, and her head dropped down on the pillow at her father's side. Clennam rose softly, opened and closed the door without a sound — Book 1, chap. xxxv. In the original serial illustrations by Phiz, the narrative-pictorial sequence moves directly from the discussion of the forthcoming wedding of Henry Gowan and Pet Meagles in the previous chapter's steel-engraving, Society Expresses its Views on a Question of Marriage (Part 10: September 1856), to the final illustration of Book the First, Poverty, the triumphal exit of the Dorrit clan from the debtors' prison, The Marshalsea becomes an orphan (Part 10: September 1856). This mid-point serial instalment ended with the architect of the Dorrit renaissance, Arthur Clennam, standing in the street outside the Marshalsea as he watches the entourage drive off.

Instead, Mahoney shows an intermediate scene in which, having delivered the good news, Arthur Clennam sensitively leaves the daughter to cope with her father's shock at the news of his release and sudden fortune, a scene which Felix Octavius Carr Darley tenderly realised in one of his engraved title-pages for the 1863 Household Edition produced as a piracy in New York, Joyful Tidings — Book I, Ch. XXXV, a study that Mahoney is not likely to have seen.

In James Mahoney's low-key illustration (the penultimate for the first book), set near the mid-point of the four-hundred-and-twenty-three-page volume, discretely the messenger of glad tidings, Arthur Clennam, with his hat on and ready to enter "the turbulent streets" (216) which are about to receive the long-consigned William Dorrit and will, at the very end of the novel receive Arthur and his bride, Amy, is caught in the act of closing the door to William Dorrit's bedroom. On the narrow bed with large pillows, the Father of the Marshalsea, still wearing his clothes and velvet skullcap, and his dutiful daughter are now both asleep, their faces betraying neither agitation nor doubt as to the veracity of Clennam's announcement. They are not merely free, but rich, and on their way in imagination to join other wealthy English expatriates across the Alps, in Italy.

The engaged reader, awaiting this climax in the Dorrit fortunes, scrutinizes the illustration proleptically, encountering the moment realised in the text some seven pages later, already having read on page 213 that Pancks has resolved Mr. Dorrit's case and that "He will be a rich man. He is a rich man. A great sum of money is waiting to be paid over to him as his inheritance" (chapter 35). Such a windfall, although not entirely unexpected, effected the release of John Dickens from the Marshalsea after his incarceration for non-payment of tradesmen's accounts of forty pounds in 1824 for a mere three months that must have seemed like an eternity to his son, working at the blacking factory, the twelve-year-old Charles, whose purgatorial class descent is partly reflected in the tribulations of the sensitive and dutiful Amy Dorrit, faithful guardian of her father in in repose.

Pictures of Amy and her father from other 19th c. editions

Left: Harry Furniss's interpretation of the scene in which William Dorrit suffers a mental and physical breakdown in Italy, Mr. Dorrit forgets himself (1910). Centre: Sol Eytinge, Juniuor's study of the pensive Amy and her self-important William Dorrit, Little Dorrit and Her Father (1867). Right: Felix Octavius Carr Darley's engraved frontispiece for the second volume in the Sheldon and Company (New York) Household Edition, Joyful Tidings — Bopok I, Ch. XXXV. (1863). [Click on images to enlarge them.]

References

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by Hablot Knight Browne ("Phiz"). The Authentic Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1901 [rpt. of the 1868 volume, based on the 30 May 1857 volume].

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Frontispieces by Felix Octavius Carr Darley and Sir John Gilbert. The Household Edition. 55 vols. New York: Sheldon & Co., 1863. 4 vols.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1867. 14 vols.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by James Mahoney. The Household Edition. 22 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1873. Vol. 5.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book, 1910. Vol. 12.

Hammerton, J. A. "Chapter 19: Little Dorrit." The Dickens Picture-Book. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. 18 vols. London: Educational Book Co., 1910. Vol. 17. Pp. 398-427.

Kitton, Frederic George. Dickens and His Illustrators: Cruikshank, Seymour, Buss, "Phiz," Cattermole, Leech, Doyle, Stanfield, Maclise, Tenniel, Frank Stone, Landseer, Palmer, Topham, Marcus Stone, and Luke Fildes. Amsterdam: S. Emmering, 1972. Re-print of the London 1899 edition.

Lester, Valerie Browne. Phiz: The Man Who Drew Dickens. London: Chatto and Windus, 2004.

"Little Dorrit — Fifty-eight Illustrations by James Mahoney." Scenes and Characters from the Works of Charles Dickens, Being Eight Hundred and Sixty-six Drawings by Fred Barnard, Gordon Thomson, Hablot Knight Browne (Phiz), J. McL. Ralston, J. Mahoney, H. French, Charles Green, E. G. Dalziel, A. B. Frost, F. A. Fraser, and Sir Luke Fildes. London: Chapman and Hall, 1907.

Schlicke, Paul, ed. The Oxford Reader's Companion to Dickens. Oxford and New York: Oxford U. P., 1999.

Steig, Michael. Dickens and Phiz. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1978.

Vann, J. Don. Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: The Modern Language Association, 1985.

Last modified 7 June 2016