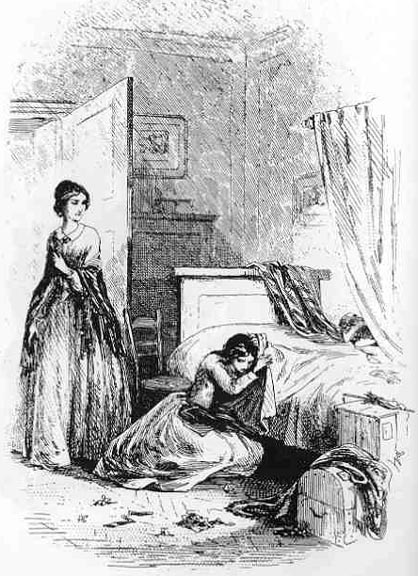

After one of the nights that I have spoken of, I came down into a greenhouse before breakfast. Charlotte (the name of my false young friend) had gone down before me, and I heard her aunt speaking to her about me, as I entered. I stopped where I was, among the leaves and listened — Book 2, chap. xxi, is the full title as given in the Harper and Brothers printing. The Chapman and Hall edition has an abbreviated version of this title: "I stopped where I was, among the leaves, and listened." Sixties' illustrator James Mahoney's forty-seventh composite woodblock illustration for Charles Dickens's Little Dorrit, Household Edition, 1873. Wood-engraving by the Dalziels, 10.5 cm high by 13.5 cm wide, p. 337, framed, under the running head "Not Much Help from Miss Wade." [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL.]

Passage Illustrated

In the family there was an aunt who was not fond of me. I doubt if any of the family liked me much; but I never wanted them to like me, being altogether bound up in the one girl. The aunt was a young woman, and she had a serious way with her eyes of watching me. She was an audacious woman, and openly looked compassionately at me. After one of the nights that I have spoken of, I came down into a greenhouse before breakfast. Charlotte (the name of my false young friend) had gone down before me, and I heard this aunt speaking to her about me as I entered. I stopped where I was, among the leaves, and listened. The aunt said, "Charlotte, Miss Wade is wearing you to death, and this must not continue." I repeat the very words I heard. Now, what did she answer? Did she say, "It is I who am wearing her to death, I who am keeping her on a rack and am the executioner, yet she tells me every night that she loves me devotedly, though she knows what I make her undergo?" No; my first memorable experience was true to what I knew her to be, and to all my experience. — Book the Second, "Riches," Chapter 21, "The History of a Self-Tormentor," p. 340.

Commentary

The first-person narrative which Miss Wade gives Arthur Clennam is a "framed tale" that can be treated as an independent short story, although it is informed by the reader's prior knowledge of Miss Wade and her treatment of Harriet Meagles ("Tattycoram"), and her utter disdain for the male sex. Moreover, in the original serial and volume editions other than the Household, Miss Wade's account of herself, given to Clennam to read on the packet-boat back to England, is not usually illustrated, perhaps because of the shift in the narrative perspective from omniscient in the novel as a whole to first-person here. In Dickens and the Short Story, Deborah A. Thomas notes the importance of the interpolated psychological study in the midst of a large-scale narrative that places the reader in this secondary character's shoes, so to speak, but with this difference: instead of accepting the judgments of the first-person narrator, the reader will consistently find Miss Wade's judgments faulty and her assessments tinged with prejudice. Again and again, beginning with the childhood incident depicted in the illustration, Miss Wade justifies herself in such a way that the astute reader is likely to see her self-centred response as warped and her judgments of others as wrong-headed as she pleads that she is imposed upon and treated with contempt resulting initially from her status as an orphan and later from her inferior status as a governess:

This impression is like a colored glass through which she persistently looks at life. As a child, she misinterprets the kindness of the girls with whom she is raised, and, like Browning's Duke who executes his Duchess for smiling indiscriminately, Miss Wade interprets any kindness shown to others by her "chosen friend" as an act of disloyalty to herself . . . . [Thomas 123]

In the illustration, a twelve-year-old Miss Wade (who looks much older) overhears a conversation between her best friend and the friend's aunt from the corner of a greenhouse. Mahoney describes the friend as slight, small for her age, and blonde, but dark-haired, sharp-featured Miss Wade as mature for her age, and apparently an astute observer of others — and yet she is wholly mistaken in her judgments of others, taking umbrage at kindness which she receives as a reminder of her class inferiority. Her psychopathology is so developed as a young adult that she consistently sees her employers as proud, spiteful, and condescending. In Mahoney's illustration of this pivotal childhood event several decades previous, Miss Wade recalls the circumstances of the overheard conversation in vivid detail, although Mahoney has had to supply the manner of dress of the three females, contrasting the light-coloured dresses of her friend and friend's aunt with the black dress and dark hair of the eavesdropper, who only vaguely resembles the Miss Wade at the beginning of Mahoney's narrative-pictorial sequence, The observer stood with her hand upon her own bosom, looking at the girl (Book 1, Chapter 2).

The events which she describes [except perhaps her perceptions of Henry Gowan] are clearly open to more interpretations than the once she puts upon them. Her fierce attachment to her childhood friend and her identification with the girl whom she later takes to live with her [Tattycoram] seem at least implicitly lesbian, and such details combine to suggest that her particular "truth" is a delusion. [Thomas 123]

Images of Miss Wade and Tattycoram, 1856 through 1910

Left: Phiz's original serial illustration depicting the emotionally distraught Harriet Meagles (a. k. a., "Tattycoram"), Under the microscope (December 1855: I: 2). Centre: Sol Eytinge, Junior's Diamond Edition character study of the severe spinster and the girl whom she has taken in, Miss Wade and Tattycoram (1867). Right: Harry Furniss's illustration of the proud, bitter spinster (right) and the rebellious maid, Tattycoram and Miss Wade (1910). [Click the on the images to enlarge them.]

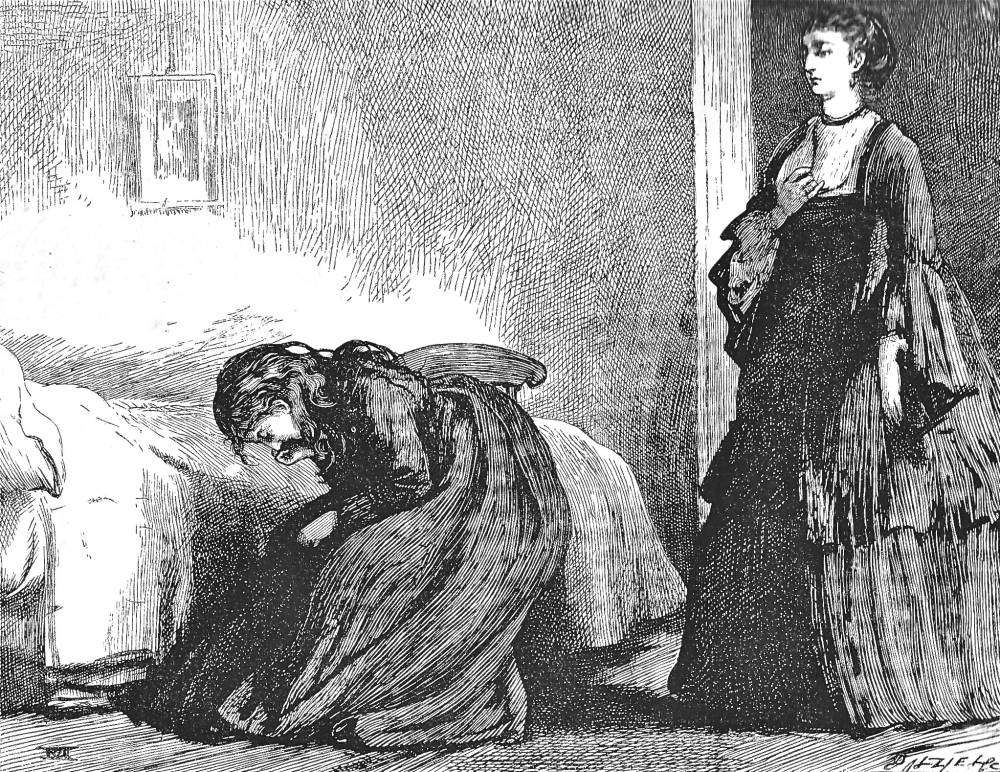

Above: Mahoney's study of the the calculating Miss Wade and the distraught Tattycoram when the latter takes refuge from the Meagles, whose attentions she interprets as mistreatment, in Book 1, Chapter 2, The observer stood with her hand upon her own bosom, looking at the girl [Click on image to enlarge it.]

References

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by Hablot Knight Browne ("Phiz"). The Authentic Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1901 [rpt. of the 1868 volume, based on the 30 May 1857 volume].

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Frontispieces by Felix Octavius Carr Darley and Sir John Gilbert. The Household Edition. 55 vols. New York: Sheldon & Co., 1863. 4 vols.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1867. 14 vols.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by James Mahoney. The Household Edition. 22 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1873. Vol. 5.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book, 1910. Vol. 12.

Hammerton, J. A. "Chapter 19: Little Dorrit." The Dickens Picture-Book. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. 18 vols. London: Educational Book Co., 1910. Vol. 17. Pp. 398-427.

Kitton, Frederic George. Dickens and His Illustrators: Cruikshank, Seymour, Buss, "Phiz," Cattermole, Leech, Doyle, Stanfield, Maclise, Tenniel, Frank Stone, Landseer, Palmer, Topham, Marcus Stone, and Luke Fildes. Amsterdam: S. Emmering, 1972. Re-print of the London 1899 edition.

Lester, Valerie Browne. Ch. 12, "Work, Work, Work." Phiz: The Man Who Drew Dickens. London: Chatto and Windus, 2004. Pp. 128-160.

"Little Dorrit — Fifty-eight Illustrations by James Mahoney." Scenes and Characters from the Works of Charles Dickens, Being Eight Hundred and Sixty-six Drawings by Fred Barnard, Gordon Thomson, Hablot Knight Browne (Phiz), J. McL. Ralston, J. Mahoney, H. French, Charles Green, E. G. Dalziel, A. B. Frost, F. A. Fraser, and Sir Luke Fildes. London: Chapman and Hall, 1907.

Schlicke, Paul, ed. The Oxford Reader's Companion to Dickens. Oxford and New York: Oxford U. P., 1999.

Steig, Michael. Dickens and Phiz. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1978.

Thomas, Deborah A. Chapter 6: "Murder and Self-Effacement." Dickens and the Short Story. Philadelphia: U. Pennsylvania Press, 1982. Pp. 110-131.

Vann, J. Don. Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: The Modern Language Association, 1985.

Last modified 15 June 2016