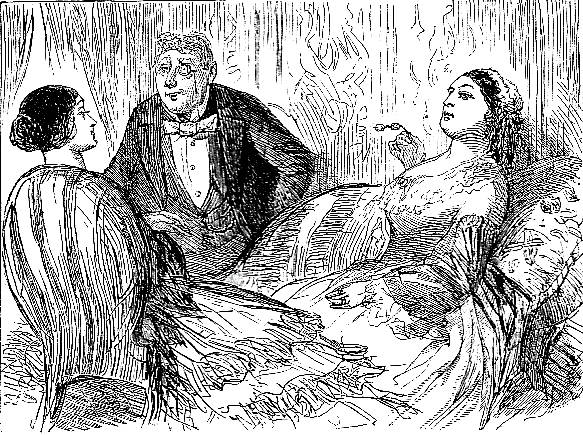

"He couldn't have a better nurse to bring him round," Mr. Sparkler made bold to opine. . . . "For a wonder I can agree with you," returned his wife, languidly turning her eyelids a little in his direction, "and can adopt your words" — Book 2, chap. xxiv, is the full title as given in the Harper and Brothers printing. The Chapman and Hall edition has an abbreviated version of this title: "For a wonder, I can agree with you." Sixties' illustrator James Mahoney's forty-ninth composite woodblock illustration for Charles Dickens's Little Dorrit, Household Edition, 1873. Wood-engraving by the Dalziels, 10.6 cm high by 13.6 cm wide, p. 353, framed, under the running head "A House Full of Mysteries." [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL.]

Passage Illustrated

Here Fanny stopped to weep, and to say, "Dear, dear, beloved papa! How truly gentlemanly he was! What a contrast to poor uncle!"

"From the effects of that trying time," she pursued, "my good little Mouse will have to be roused. Also, from the effects of this long attendance upon Edward in his illness; an attendance which is not yet over, which may even go on for some time longer, and which in the meanwhile unsettles us all by keeping poor dear papa's affairs from being wound up. Fortunately, however, the papers with his agents here being all sealed up and locked up, as he left them when he providentially came to England, the affairs are in that state of order that they can wait until my brother Edward recovers his health in Sicily, sufficiently to come over, and administer, or execute, or whatever it may be that will have to be done."

"He couldn't have a better nurse to bring him round," Mr. Sparkler made bold to opine.

"For a wonder, I can agree with you," returned his wife, languidly turning her eyelids a little in his direction (she held forth, in general, as if to the drawing-room furniture), "and can adopt your words. He couldn't have a better nurse to bring him round. There are times when my dear child is a little wearing to an active mind; but, as a nurse, she is Perfection. Best of Amys!"

Mr. Sparkler, growing rash on his late success, observed that Edward had had, biggodd, a long bout of it, my dear girl. — Book the Second, "Riches," Chapter 24, "The Evening of a Long Day," p. 357.

Commentary

Three months after marriage, the Sparklers find that domesticity is anything but romantic on a hot summer evening in London as Fanny constantly criticizes and belittles Edmund for being more than a bit obtuse. Having married into society, Fanny expects to entertain society and to be invited to social affairs, despite the fact that she is pregnant and in mourning. She is determined to break free of her boring domesticity. Edmund is no conversationalist — but she knew his intellectual limitations before she married him, partly to take revenge for Mrs. Merdle's slighting her. Technically, of course, she is mourning for her father and uncle, but she seems to have little genuine emotion about their sudden deaths in Rome. Her pregnancy is yet another reason why they receive neither callers nor invitations. Edmund ventures to suggest that, once Tip has recovered from a bout of malaria and returned with Amy from Italy, Amy might keep her company. Fanny expresses skepticism about Amy's suitability as a companion in terms of participation in London society: "Darling little thing! Not, however, that Amy would do here alone" (357). Here, Edmund Sparkler asserts that his sister-in-law, although an excellent nurse, would not be suitable in a social role — and his wife thoroughly concurs — apparently such concurrence being highly unusual in their daily conversations. In a moment, a knock at the door will interrupt these deliberations as the banker, Mr. Merdle, the couple's father-in-law, will pay a call and ominously ask to borrow a pen-knife.

Mahoney's illustration depicts Edmund as virtually unchanged, with his monocle still implying his limited intellectual capacity and high society background. On the other hand, Fanny is looking more and more like her mother-in-law, Mrs. Merdle, and less and less like the tall, slender dancer who watched her uncle practising his clarionet in Book One, Chapter 20: They spoke no more, all the way back to the lodging where Fanny and her uncle lived. . . . A rather mournful Italian landscape in oils above Fanny sets a sombre mood for the conversation, and serves as a reminder of the deaths of William and Frederick Dorrit in Rome. Having matured suddenly into a respectable matron, Fanny finds the company of her husband as interesting as the houseplant beside which Mahoney has positioned him. The imperial posture of Mrs. Sparkler recalls a portrait of Mrs. Merdle in the original engravings by Phiz, Society Expresses its Views on a Question of Marriage (September 1856). In short, in taking on Edmund, Mahoney seems to be implying that she has replaced his mother as a controlling consciousness and severe judge.

Images of The Sparkers, Fanny and Edmund, 1857 through 1910

Above: Phiz's original study of the newlyweds visited by Edmund's stepfather just prior to Mr. Merdle's committing suicide, Mr. Merdle becomes a Borrower (Part 17: April 1857, II: 24). [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Above: Sol Eytinge, Junior's Diamond Edition character study of Mrs. Merdle, her son, and Fanny Dorrit, Mrs. Merdle, Mr. Sparkler, and Fanny (1867). [Click the on the image to enlarge it.]

Above: Harry Furniss's derivative study of Mr. Merdle's visiting the newlyweds, Mr. Merdle gives the Sparklers a call (1910). [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

References

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by Hablot Knight Browne ("Phiz"). The Authentic Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1901 [rpt. of the 1868 volume, based on the 30 May 1857 volume].

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Frontispieces by Felix Octavius Carr Darley and Sir John Gilbert. The Household Edition. 55 vols. New York: Sheldon & Co., 1863. 4 vols.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1867. 14 vols.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by James Mahoney. The Household Edition. 22 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1873. Vol. 5.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book, 1910. Vol. 12.

Hammerton, J. A. "Chapter 19: Little Dorrit." The Dickens Picture-Book. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. 18 vols. London: Educational Book Co., 1910. Vol. 17. Pp. 398-427.

Kitton, Frederic George. Dickens and His Illustrators: Cruikshank, Seymour, Buss, "Phiz," Cattermole, Leech, Doyle, Stanfield, Maclise, Tenniel, Frank Stone, Landseer, Palmer, Topham, Marcus Stone, and Luke Fildes. Amsterdam: S. Emmering, 1972. Re-print of the London 1899 edition.

Lester, Valerie Browne. Ch. 12, "Work, Work, Work." Phiz: The Man Who Drew Dickens. London: Chatto and Windus, 2004. Pp. 128-160.

"Little Dorrit — Fifty-eight Illustrations by James Mahoney." Scenes and Characters from the Works of Charles Dickens, Being Eight Hundred and Sixty-six Drawings by Fred Barnard, Gordon Thomson, Hablot Knight Browne (Phiz), J. McL. Ralston, J. Mahoney, H. French, Charles Green, E. G. Dalziel, A. B. Frost, F. A. Fraser, and Sir Luke Fildes. London: Chapman and Hall, 1907.

Schlicke, Paul, ed. The Oxford Reader's Companion to Dickens. Oxford and New York: Oxford U. P., 1999.

Steig, Michael. Dickens and Phiz. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1978.

Vann, J. Don. Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: The Modern Language Association, 1985.

Last modified 16 June 2016