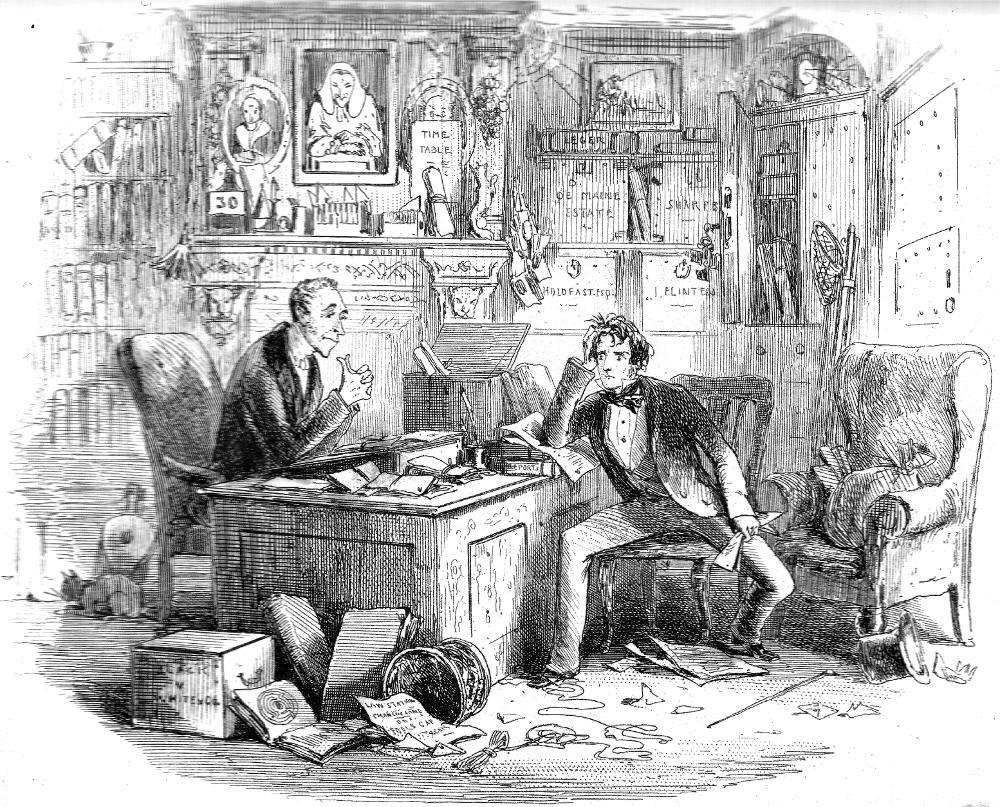

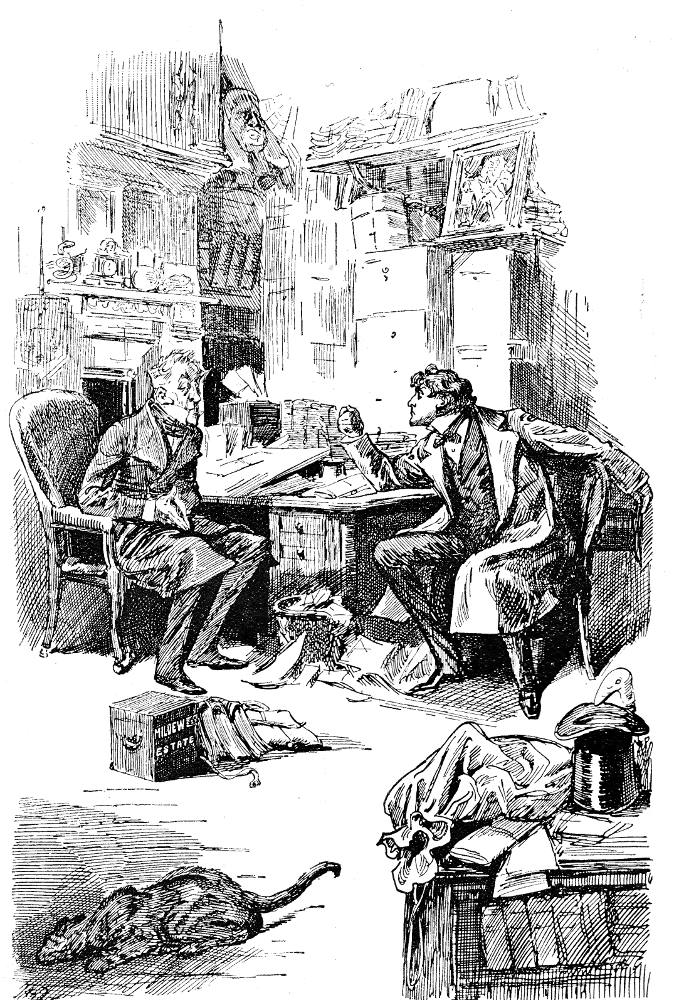

Attorney and Client: Fortitude and Impatience by "Phiz" (Hablot Knight Browne) for Bleak House, facing p. 388 (ch. 39, "Attorney and Client"). 4 3/16 x 5 inches. (11.5 cm by 13 cm), vignetted. For commentary and text illustrated, see below. [Return to text of Steig; click on the image to enlarge it.]

Sketches for this plate (from Stieg, Dickens and Phiz)

Passage Illustrated: The Cool, Methodical, and Self-serving Attorney

Vholes, sitting with his arms on the desk, quietly bringing the tips of his five right fingers to meet the tips of his five left fingers, and quietly separating them again, and fixedly and slowly looking at his client, replies, "A good deal is doing, sir. We have put our shoulders to the wheel, Mr. Carstone, and the wheel is going round."

"Yes, with Ixion on it. How am I to get through the next four or five accursed months?" exclaims the young man, rising from his chair and walking about the room.

"Mr. C.," returns Vholes, following him close with his eyes wherever he goes, "your spirits are hasty, and I am sorry for it on your account. Excuse me if I recommend you not to chafe so much, not to be so impetuous, not to wear yourself out so. You should have more patience. You should sustain yourself better."

"I ought to imitate you, in fact, Mr. Vholes?" says Richard, sitting down again with an impatient laugh and beating the devil's tattoo with his boot on the patternless carpet.

"Sir," returns Vholes, always looking at the client as if he were making a lingering meal of him with his eyes as well as with his professional appetite. "Sir," returns Vholes with his inward manner of speech and his bloodless quietude, "I should not have had the presumption to propose myself as a model for your imitation or any man's. Let me but leave the good name to my three daughters, and that is enough for me; I am not a self-seeker. But since you mention me so pointedly, I will acknowledge that I should like to impart to you a little of my — come, sir, you are disposed to call it insensibility, and I am sure I have no objection — say insensibility — a little of my insensibility."

"Mr. Vholes," explains the client, somewhat abashed, "I had no intention to accuse you of insensibility."

"I think you had, sir, without knowing it," returns the equable Vholes. "Very naturally. It is my duty to attend to your interests with a cool head, and I can quite understand that to your excited feelings I may appear, at such times as the present, insensible. My daughters may know me better; my aged father may know me better. But they have known me much longer than you have, and the confiding eye of affection is not the distrustful eye of business. Not that I complain, sir, of the eye of business being distrustful; quite the contrary. In attending to your interests, I wish to have all possible checks upon me; it is right that I should have them; I court inquiry. But your interests demand that I should be cool and methodical, Mr. Carstone; and I cannot be otherwise — no, sir, not even to please you." [Chapter XXXIX, "Attorney and Client," 388; Project Gutenberg etext (see bibliography below)]

Commentary

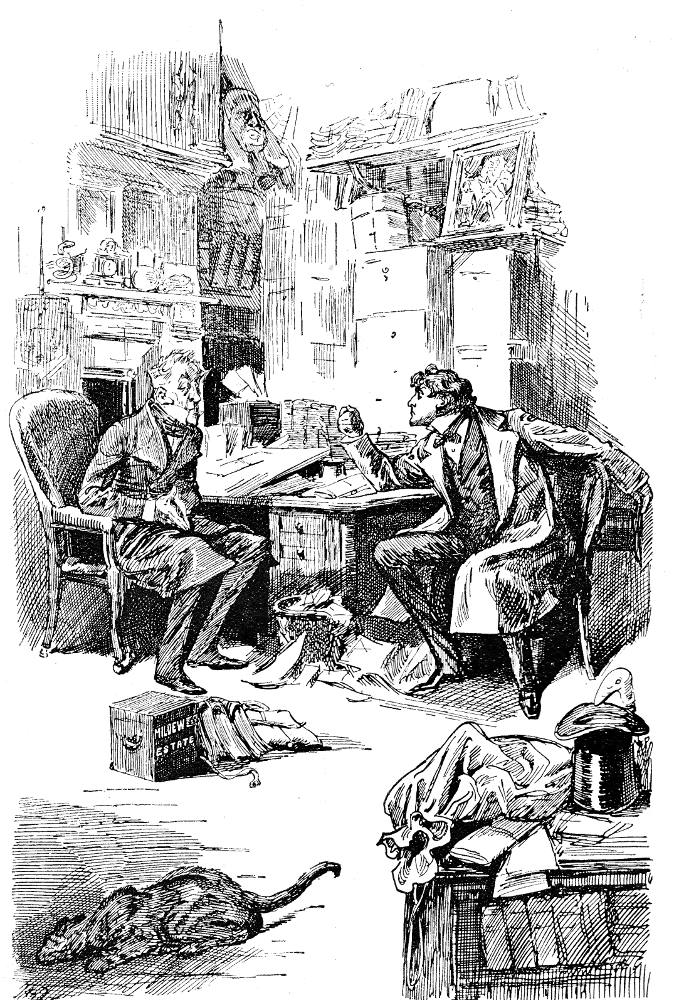

Harry Furniss's dual portrait of the unscrupulous attorney and his desperate client, just billed for twenty pounds: Mr. Vholes and Richard (1910).

In the depiction of Mr. Vholes, the eminently respectable solicitor for whose parasitic survival the archaic procedures of Chancery must be maintained, Phiz indulges in his last big splurge of emblematic invention for Dickens. The techniques of Attorney and Client, fortitude and impatience (ch. 39) are perhaps less brilliant than those of the Turveydrop-Chadband series, but a close examination of this etching's details and process of creation reveals much about one aspect of Phiz's art. [Steig, 143]

On a first look it seems that this illustration contains a simple representation of a moment in the narrative: Richard sits, looking anxious and distracted, whilst Vholes prevaricates, with a world-weary expression on his face. It is interesting to note that the two characters are not caricatured, and in Dickens and Phiz Michael Steig has noted that Phiz's illustrations for Bleak House move away from caricature towards a darker, more naturalistic type of illustration. Richard in particular still looks rather idealised — he is very pretty, with almost feminine features, emphasising his youth and perhaps linking him with Ada and Esther, the other wards of Jarndyce — but his expression does a good job of evoking his frustration and desperation.

The title, however, rather than suggesting simply the naturalistic illustration of a confrontation in the text, calls to mind the satirical work of William Hogarth and such oppositions as "Industry and Idleness". We are therefore encouraged by this accompanying text to look for more emblematic details within the illustration. Steig does a very thorough job of identifying these in his chapter on Bleak House, but it is worth mentioning a few: the cat and mouse (mentioned in Dickens' text) suggesting Richard's position under threat from Vholes, a maze on the page of an open book suggesting the legal maze of Chancery (and perhaps also the windings of Dickens' own narrative, given that the maze appears in a book) the reams of tape that unspool on the ground suggesting the mass of legal red tape that ensnares Richard, the short-sighted judge whose portrait hangs on the wall and so on. We also have spiderwebs on the wall, suggesting, as Steig points out, the law's delay, but also possibly suggesting another image of Richard caught in Vholes' web, unable to extricate himself and waiting to be consumed by the Chancery case.

Dickens's text seems to justify such a treatment — his description of Richard in this scene reads that he is: "half sighing and half groaning; rests his aching head upon his hand, and looks the portrait of Young Despair." Richard is described as an allegorical type, justifying such further emblematic developments as the spider's web in the illustration. In fact these elements also fulfill a simple descriptive function, as Dickens mentions that the office has a "congenial shabbiness" and is dusty and dirty. Such details as the spider's web are therefore simultaneously both naturalistic and emblematic, and thus the illustration works on at least two different levels.

However, one feature that is notable in some of the later drawings, such as Sunset in the Long Drawing-Room at Chesney Wold and The Mausoleum at Chesney Wold is absent in this illustration. That feature is an atmosphere of gloom and darkness, an atmosphere that is often evoked in the novel through such features as the fog that saturates London and the diseased murk of the pauper's graveyard and Tom All-Alone's. Phiz achieves such an atmosphere in these two illustrations, among others, in part because of the absence of human figures in these scenes. The darkness creates an atmosphere of threat and despair that is very powerful, and it is significant that although the novel ends reasonably happily, with Esther married to the man she loves and with a family to care for, the final illustration is of the mausoleum where Lord and Lady Deadlock rest. Lady Deadlock, who is in many ways at the centre of the novel's narrative (she is Esther's mother, Tulkinghorn's quarry, Nemo's mistress, and she inhabits both the grand aristocratic world of Chesney Wold as Lady Deadlock and also the stagnant world of Tom All-Alone's in disguise and in death) lives and dies wretchedly, and it is this that the final illustration meditates upon, not Esther's domestic bliss.

The atmosphere of threat and darkness suggested by the gloomy atmosphere of these illustrations might well have amplified the sense of threat hanging over Richard in a more direct way than the emblems of the spider's web or the cat and mouse that Phiz uses in his more Hogarthian vein. However, it is questionable whether such a presentation would have meshed well with an attempt to portray the characters in this moment. The two other plates I have mentioned work so well because we are shown a place whose atmosphere works an emotional effect upon the viewer. In trying to represent the emotion of character, Phiz seems to have less freedom to create such an evocative setting. [Lucy Barnes, MA Candidate, English 2560O, "Victorian Literature and the Visual Arts," Brown University 2007]

Q. D. Leavis has criticized this Vholes-Carstone plate on the grounds that it depicts Mr. Vholes in terms of a "Hogarthian satiric mode" which is no longer Dickens', and that Phiz "conveys nothing of the sinister ethos that emanates from Mr. Vholes in the text of the novel." (Leavis, p. 360.) Mrs. Leavis' assumption is that the only proper function of illustrations like Browne's is to mirror the import of the text, but, as I have shown, an illustration may present a point of view and bring out aspects which are not overtly expressed in the text. Mrs. Leavis also fails to differentiate multiple purposes in Dickens. In describing Vholes's office, Dickens himself employs Hogarthian techniques, first conveying the decay and dirt, the "congenial shabbiness" of Symond's Inn, and then the "legal bearings of Mr. Vholes." The office is described in detail worthy of Hogarth, and then the narrative takes another turn and speaks of the "great principle of English law," i.e., "to make business for itself' (ch. 39, p. 386). Throughout the page-long discussion of the 'Wholeses," Dickens uses metaphors which border on the emblematic: the law is a "monstrous maze," Vholes and his tribe, cannibals, and the [143/144] lawyer is "a piece of timber, to shore up some decayed foundation that has become a pit-fall and a nuisance" (p. 386). In the interview with Richard, Dickens describes some blue bags stuffed in the way "the larger sort of serpents are in their first gorged state," while the office is "the official den" of predators (P. 387). And most Hogarthian of all, and a detail which turns up in the illustration, "Mr. Vboles, after glancing at the official cat who is patiently watching a mouse's hole, fixes his charmed gaze again on his young client" (p. 388). [Steig, 143-144]

Other Series' Illustrations of Richard Carstone's devious solicitor (1867 through 1910)

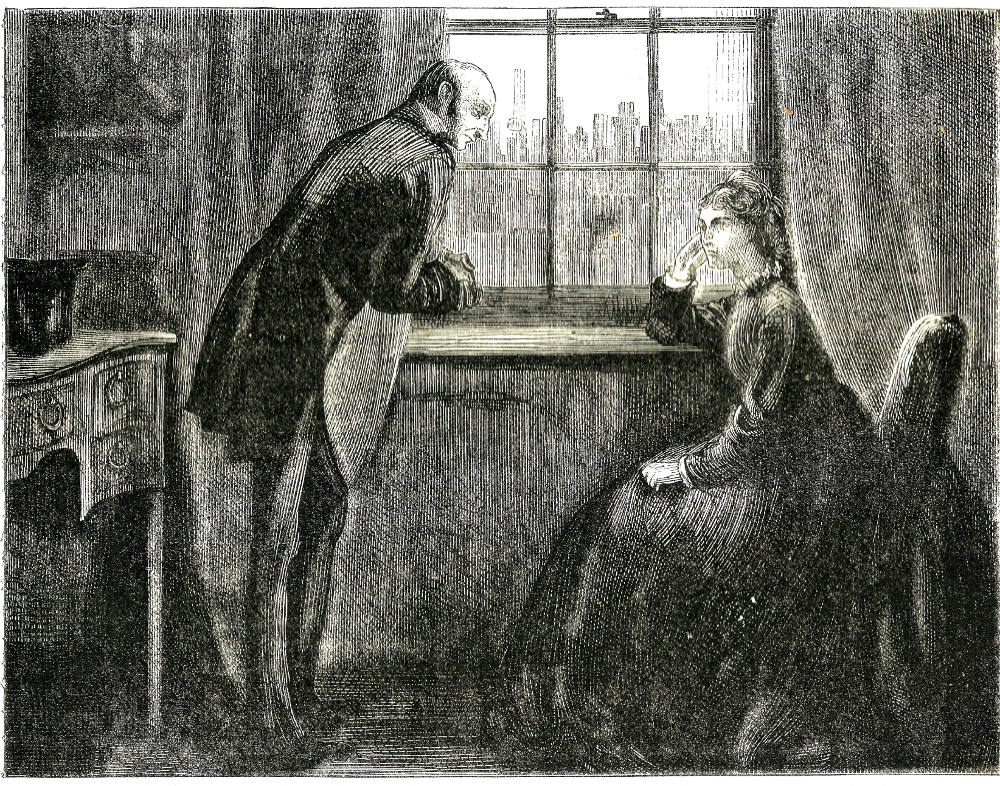

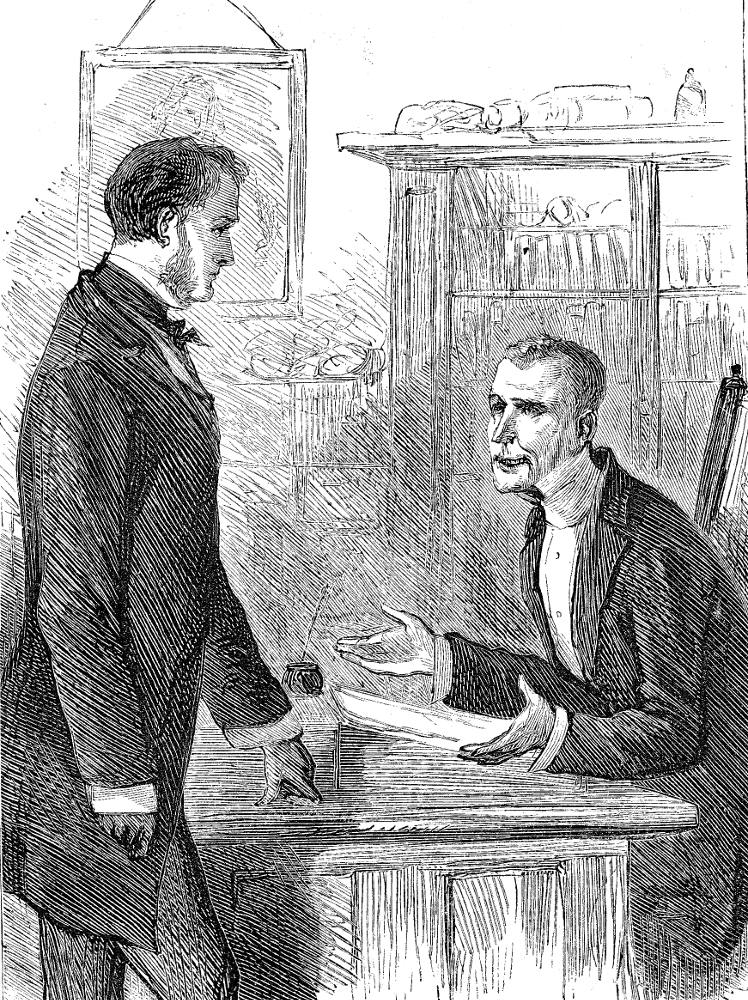

Left: Fred Barnard's "strait" rather than satirical depiction of the lawyer Vholes, with a skeptical Esther Summerson: "Miss Summerson," said Mr. Vholes, very slowly rubbing his gloved hands, . . . ." This was an ill-advised marriage of Mr. C.'s." (1873). Centre: Sol Eytinge, Jr.'s dual portrait of a different pairing: Mr. Woodcourt and Vholes (1867). Right: Harry Furniss's satirical portrait of the unscrupulous lawyer: Mr. Vholes and Richard (1910).

Related Material, including Other Illustrated Editions

- Bleak House (homepage)

- Sir John Gilbert's Frontispiece in the New York edition (Vol. 1, 1863)

- O. C. Darley's Frontispiece in the New York edition (Vol. 2, 1863)

- O. C. Darley's Frontispiece in the New York edition (Vol. 3, 1863)

- O. C. Darley's Frontispiece in the New York edition (Vol. 4, 1863)

- Sol Eytinge, Junior's 16 Diamond Edition Illustrations (1867)

- Fred Barnard's 61 illustrations for the Household Edition (1872)

- Harry Furniss's 28 illustrations for the Charles Dickens Library Edition (1910)

- Kyd's five Player's Cigarette Cards, 1910

Image scan and text by George P. Landow; additional text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image, and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Dickens, Charles. Bleak House. Illustrated by Hablot Knight Browne ("Phiz"). London: Bradbury & Evans. Bouverie Street, 1853.

_______. Bleak House. Project Gutenberg etext prepared by Donald Lainson, Toronto, Canada (charlie@idirect.com), with revision and corrections by Thomas Berger and Joseph E. Loewenstein, M.D. Seen 9 November 2007.

Steig, Michael. Chapter 6. "Bleak House and Little Dorrit: Iconography of Darkness." Dickens and Phiz. Bloomington & London: Indiana U. P., 1978. 131-172.

Vann, J. Don. "Bleak House, twenty parts in nineteen monthly instalments, October 1846—April 1848." Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: The Modern Language Association, 1985. 69-70./

Created 14 November 2007 Last modified 16 March 2021