Pen and ink self portait, © National Portrait Gallery, London, NPG 3034, 1891.

inley Sambourne was born at 15 Lloyd Square, Clerkenwell, to middle class parents. From an early age he showed promise as an artist and was enrolled at the South Kensington School of Art in 1860. As Juliet McMaster says, "His formal training in Art was relatively cursory" (65): shortly afterwards it seems that financial troubles overtook the family and they could no longer afford the fees. As the boy was interested in machinery as well as art he was apprenticed to John Penn and Sons, marine engineers at Greenwich in 1861. He was soon promoted to the drawing office and remained there quite happily until 1867 when a chance encounter with the editor of Punch led to an offer of freelance work. Here he soon began to make a mark with a series on women’s fashions, lampooning their exaggerated hairstyles and dressing ladies as insects, birds, fish or fruit. In 1871 he was given a seat at the editorial board where he worked as a junior to John Tenniel, who is best known today as the artist of Alice in Wonderland, but was chief cartoonist at Punch for fifty years.

As well as filling the corners of the magazine with small vignettes Sambourne did the headings for a regular article on political affairs, the Essence of Parliament, where he showed himself to be a master of decorative capital letters. In the 80s his forte was the Fancy Portrait series which ran to nearly 200 drawings of prominent men — and a few women — usually involving a pun on their name: contributors to Punch loved to insert puns, some good, some bad, at every opportunity. During these two decades Sambourne also ran a series on the Royal Academy, whose annual exhibition, opening at the beginning of May, was the first big event of the London season. It was natural for an artist to be interested in the rapid monetary and social progress of so many contemporary oil painters, but there was also a sense of grievance among the practitioners of ‘Black and White’ that they were not permitted to exhibit there until 1885. In the 90s Sambourne graduated to more serious political subjects, parodying ministers of state at home, the expansion of the British Empire, the Boer War, and the awkward relationship with the Kaiser.

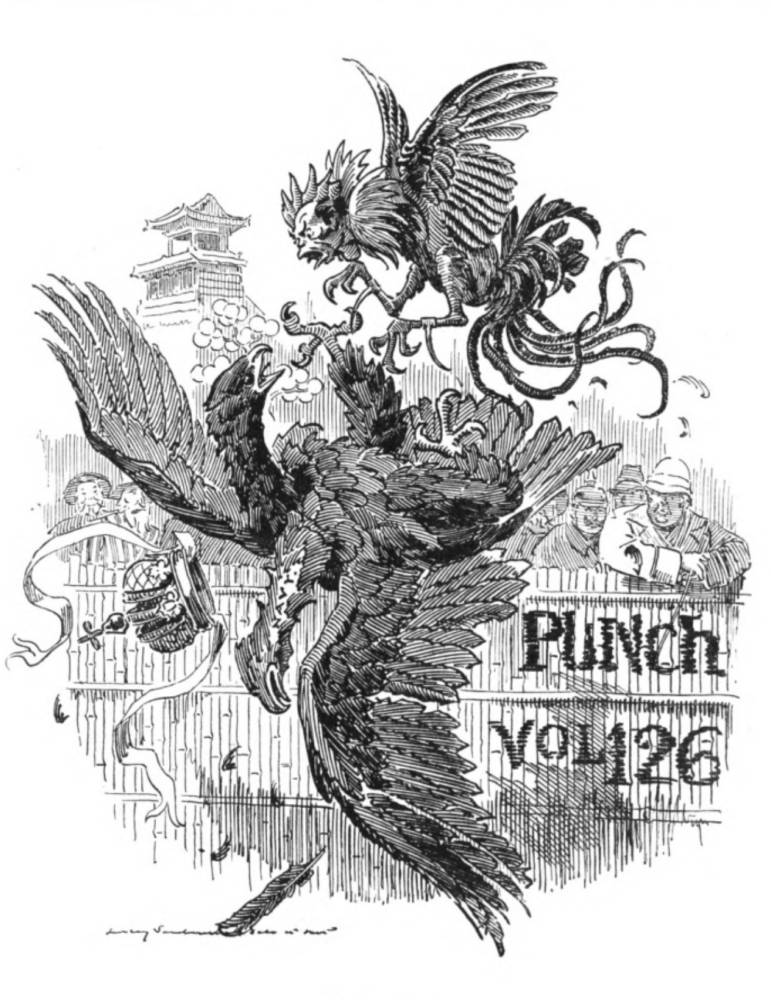

On Tenniel’s retirement at the end of 1900 Sambourne took over the position of 'First Cartoon’ which gave him the opportunity to comment more often on foreign affairs. His cartoons on the progress of the Boer War, the authoritarian attitude of the Tsar, and the Russo-Japanese conflict of 1904 are among his best work. Sadly this was not followed by the hoped for knighthood, bestowed on Tenniel and (later) on several other Punch contributors, so his fame now rests more on the house he left behind — now preserved as a museum — than on his life’s work.

Sambourne married in 1874 and with the help of his wife’s parents moved into 18 Stafford Terrace, Kensington. This he furnished in the ‘artistic style’ popular at the time, and it remains a wonderfully complete example of a middle class home of this period. In 1882 he and his wife Marion began to keep diaries of day to day events which, along with a large collection of letters and memorabilia, provide a fascinating glimpse into the busy life of a typical Victorian family.

Left to right: (a) Sambourne's striking title page for Punch, Vol. 126 (1904): Japan’s defeat of Russia in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-05. (b) "The centrepiece of the house" (Robbins et a. 27): the drawing room at 18, Stafford Terrace, looking towards Sambourne's workspace at the rear. (c) Cover of Sambourne's edition of The Water Babies. [Click on all the images to enlarge them, and for more information about them]

Sambourne also preserved many of his own drawings and photographs. The latter hobby he took up in 1884 and it soon became a consuming passion. On the whole artists were not keen on photography; it was a rival which they feared would threaten their livelihood, so although many painters began using it as an aide this was usually kept secret. Sambourne however never concealed his enthusiasm. He regularly posed his family and servants in the attitudes he needed for his weekly cartoons, and when mocked for doing so wrote an impassioned defence in a short-lived periodical, The Minster:

Picture or drawing should stand or fall by what it is in itself, and not by the means to render the production more perfect. Photography is an impossible master but a very useful slave, at any rate in black and white work.... If a drawing has to be designed and finished in a few hours, how can that short time be spent in going out endeavouring to get to nature direct, or to a model to correct from? No two men, if they are original, have the same method of work: some may be content to indicate and leave details alone, others have a striving after accuracy and truth; and it is, as far as my abilities will allow, a wish to be correct in everything that has made me form, at great expense and labour, a collection which is to me a sort of pictorial Encyclopedia, from which my designs may be verified in detail — but there it ends. Photography can neither design nor give style or technique in drawing. To me, as far as details go, it is the nearest approach I can get to working at the original, and that is all (as I have not a kaleidoscopic memory) I want. I am second to none in admiration of all true artistic work — at the same time I hold that not to make use of one of man’s most marvellous inventions (for photography is such) is akin to our friend the ostrich who pokes his head in the sand, or an individual who prefers to walk instead of saving his legs by getting into an express train. [84]

Sambourne was a prolific worker: he did occasional commissions for other magazines besides Punch and illustrated more than twenty books, most of which have dropped into obscurity. The 1885 edition of The Water Babies by Charles Kingsley, with 100 drawings, is his most enduring and best known work. In summing up her own views on Sambourne, McMaster writes, "Sambourne's stance between the graphic image, the woodcut, and the photograph marks him as an artist poised between the old reproductive technologies and the new" (76).

Bibliography

McMaster, Juliet. “‘That Mighty Art of Black-and-White’: Linley Sambourne, Punch and the Royal Academy.” The British Art Journal. 9/2 (2008): 62–76. Available on Jstor.

Nicholson, Shirley. A Victorian Household: Based on the Diaries of Marion Sambourne. 3rd ed. Stroud, Glos.: Sutton, 1994. [Review of the first edition, by John Hilary.]

Ormond, Leonee. Linley Sambourne, illustrator and Punch Cartoonist. London: Paul Holberton, 2010.

Robbins, Daniel, Reena Suleman, and Pamela Hunter. Linley Sambourne House, 18 Stafford Terrace, Kensington. The Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea Library and Arts Service, 2003.

Sambourne, Linley. "The Progress of Black and White Art (Nineteenth Century)." The Minster. July 1895: 82-92.

Scully, Richard. Eminent Victorian Cartoonists. The Cartoon Society, 2018.

Simon, Robert, ed. Public Artist, Private Passions: The World of Edward Linley. British Art Journal, 2001 (catalogue to an exhibition of Sambourne’s photographs in 2001).

Created 14 November 2021