[Clark's highly opinionated piece, which first appeared in Arts and Crafts Essays by Members of the Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society, is particularly critical of Pugin — see the commentary at the end. Numbers in square brackets indicate page numbers in the original. — Jacqueline Banerjee]

In these days there is a tendency to judge the merits of stained glass from the standpoint of the archaeologist. It is good or bad in so far as it is directly imitative of work of the fourteenth or fifteenth century. The art had reached to a surprising degree of beauty and perfection in the fifteenth century, and although under the influence of the Renaissance some good work was done, it rapidly declined only to lift its head once more with the revived study of the architecture of the Middle Ages.

The burning energy of Pugin, which [98/99] nothing could escape, was directed towards this end, but the attainment of a mere archaeological correctness was the chief aim in view. The crude draughtsmanship of the ancient craftsman was diligently imitated, but the spirit and charm of the original was lost, as, in a mere imitation, it must be. In the revival of the art, whilst there was an attempt to imitate the drawing, there was no attempt to reproduce the quality of the ancient glass. Thus, brilliant, transparent, and unbroken tints were used, lacking all the richness and splendour of colour so characteristic of the originals. Under these conditions of blind imitation the modern worker in stained glass produced things probably more hideous than the world ever saw before.

Departing altogether from the traditions of the mediaeval schools, whether [99/100] ancient or modern, there has arisen another school which has found its chief exponents at Munich. The object of these people has been, ignoring the condition under which they must necessarily work, to produce an ordinary picture in enamelled colours upon sheets of glass. The result has been the production of mere transparencies no better than painted blinds.

What then, it may be asked, are the limiting conditions, imposed upon him by the nature of the materials, within which the craftsman must work to produce a satisfactory result ?

In the first place, a stained glass window is not an easel picture. It does not stand within a frame, as does the easel picture, in isolation from the objects surrounding it; it is not even an object to be looked at by itself; its duty is, not only to be beautiful, but to play its part [100/101] in the adornment of the building in which it is placed, being subordinated to the effect the interior is intended to produce as a whole. It is, in fact, but one of many parts that go to produce a complete result. A visit to one of our mediaeval churches, such as York Minster, Gloucester Cathedral, or Malvern Priory, church buildings, which still retain much of their ancient glass, and a comparison of the unity of effect there experienced with the internecine struggle exhibited in most buildings furnished by the glass painters of to-day, will surely convince the most indifferent that there is yet much to be learned.

Secondly, the great difference between coloured glass and painted glass must be kept in view. A coloured glass window is in the nature of a mosaic. Not only are no large pieces of glass used, but each piece is separated from [101/102] and at the same time joined to its neighbouring glass by a grooved strip of lead which holds the two. "Coloured glass is obtained by a mixture of metallic oxides whilst in a state of fusion. This colouring pervades the substance of the glass and becomes incorporated with it." (1) It is termed "pot-metal." An examination of such a piece of glass will show it to be full of varieties of a given colour, uneven in thickness, full of little air-bubbles and other accidents which cause the rays of light to play in and through it with endless variety of effect. It is the exact opposite to the clear sheet of ordinary window-glass.

To build up a decorative work (and such a form of expression may be found very appropriate in this craft) in coloured [102/103] glass, the pieces must be carefully selected, the gradations of tint in a given piece being made use of to gain the result aimed at. The leaded "canes" by which the whole is held together are made use of to aid the effect. Fine lines and hatchings are painted as with "silver stain," and in this respect only is there any approach to enamelling in the making of a coloured glass window. The glass mosaic as above described is held in its place in the window by horizontal iron bars, and the position of these is a matter of some importance, and is by no means overlooked by the artist in considering the effect of his finished work. A well-designed coloured glass window is, in fact, like nothing else in the world but itself. It is not only a mosaic; it is not merely a picture. It is the honest outcome of the use of glass for making a beautiful window which shall transmit light and [103/104] not look like anything but what it is. The effect of the work is obtained by the contrast of the rich colours of the pot -metal with the pearly tones of the clear glass.

We must now describe a painted window, so that the distinction between a coloured and a painted window may be clearly made out. Quoting from the same book as before — "To paint glass the artist uses a plate of translucent glass, and applies the design and colouring with vitrifiable colours. These colours, true enamels, are the product of metallic oxides combined with vitreous compounds called fluxes. Through the medium of these, assisted by a strong heat, the colouring matters are fixed upon the plate of glass." In the painted window we are invited to forget that glass is being used. Shadows are obtained by loading the surface with [104/105] enamel colours; the fullest rotundity of modelling is aimed at; the lead and iron so essentially necessary to the construction and safety of the window are concealed with extraordinary skill and ingenuity. The spectator perceives a hole in the wall with a very indifferent picture in it — overdone in the high lights, smoky and unpleasant in the shadows, in no sense decorative. We need concern ourselves no more with painted windows; they are thoroughly false and unworthy of consideration.

Of coloured or stained windows, as they are more commonly called, many are made, mostly bad, but there are amongst us a few who know how to make them well, and these are better than any made elsewhere in Europe at this time.

Note

1. Industrial Arts, "Historical Sketches," p. 195, published for the Committee of Council on Education. Chapman and Hall.

Commentary by Jacqueline Banerjee

Somers Clarke (1841-1926) was primarily an architect — also (fashionably at this time) an Egyptologist. In this piece, he shows a good understanding of A. W. N. Pugin's character (his "burning energy ... which nothing could escape") but no appreciation of his struggles to revive the lost art of medieval stained glass techniques. While correctly interpreting Pugin's aim to emulate the style as well as the technique of medieval craftsmen, he mistakenly sees such work as "blind imitation" (99), and he can have had no idea of Pugin's continual modifications in design, or how he aimed at subtleties and half-tints as well as richness, purity, clarity and so on. Pugin fired off letters of complaint to his various glassmakers (including even John Hardman), when they failed to produce the desired effects.

Moreover, Clarke seems to forget that producing "an ordinary picture in enamelled colours upon sheets of glass" had been standard practice in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. There was no need to turn to Germany for examples. Sir Joshua Reynolds himself had painted the great west window of New College, Oxford's chapel — though few would call that no better than a "painted blind."

However, Clarke's description of the different processes involved, and the advantages of the medieval technique, is perfectly sound. Pugin himself would have agreed wholeheartedly with Clarke's general conclusion that picture windows are "thoroughly false and unworthy of consideration."

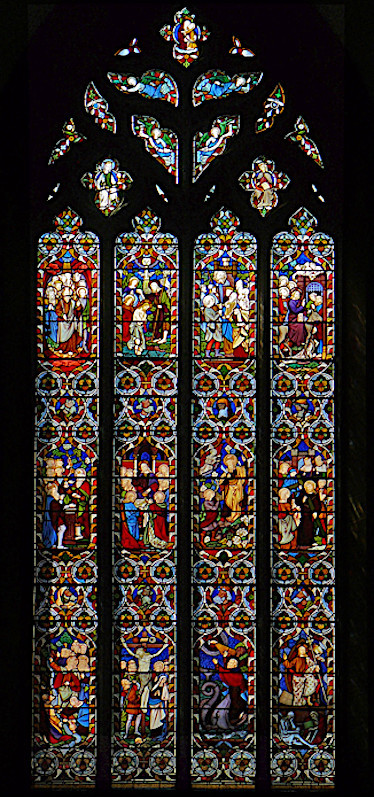

Too "brilliant"? Melchizedek offers bread and wine to Abraham, in one of Pugin's chancel windows at Our Ladye Star of the Sea, Greenwich (1851).

It is true that Pugin was a pioneer, with all the disadvantages that that entails: later developments in both materials and techniques did bring improvements in stained glass making, and, as time went by, experimentation brought greater freedom of expression, producing distinctive styles like that of Edward Burne-Jones — just to give the most obvious example. Burne-Jones's windows in St Philip's Cathedral, Birmingham, are only a stone's-throw away from Pugin's in St. Chad's Roman Catholic Cathedral, but in the decades that separate the two sets of windows a huge distance has been crossed. Thus Clarke's last claim seems perfectly valid: by the later part of the century there were indeed "a few who know how to make [stained glass windows] well, and these are better than any made elsewhere in Europe at this time." But there was no need to say this at the expense of Pugin, many of whose windows, even if produced in the earlier part of the period, are also very beautiful.

Bibliography

Arts and Crafts Essays by Members of the Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society. Preface by William Morris. London: Rivington, Percival & Co., 1893. pp. 98-105. Internet Archive version of a copy in the University of California Libraries. Web. 28 January 2013.

Last modified 28 January 2013