2. "My dear, romances are pernicious": Shirley

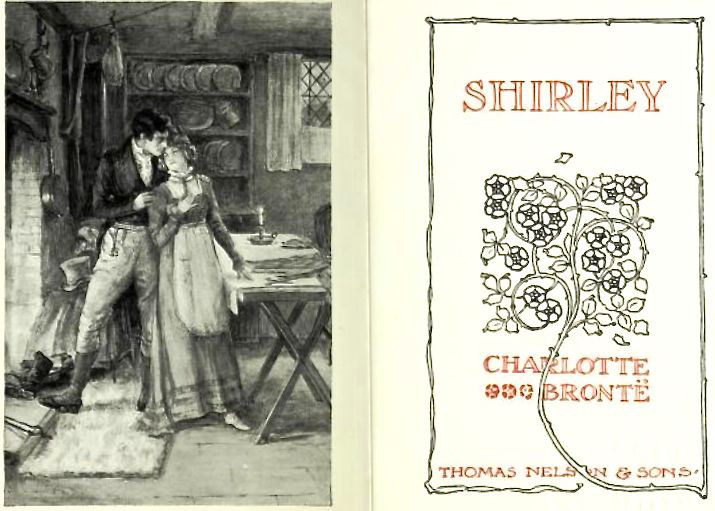

Frontispiece and title page of the Nelson edition, the frontispiece captioned, "Moore placed his hand on his cousin's shoulder, stooped, and left a kiss on her forehead."

Charlotte Brontë herself calls her improbable episodes "unthought-of turns" (Letters 2: 10). They mark crises in the narrative, moments when her heroines feel most intensely of all, and which settle their fates in a positive way. In Shirley, too, there is such an episode. Caroline Helstone had fallen in love with Robert Moore, the Yorkshire mill-owner. Her "beacon ... quenched" by the thought of Robert's involvement with her new friend Shirley Keeldar (398), she is at her very lowest ebb when Shirley's former governess, Mrs Pryor, reveals that she is her own long-lost mother. The astonishing disclosure recalls the "haloed face" that the young Jane Eyre half-expects to materialise above her in the red-room at Gateshead (18), and the supernatural voice that bids her to "flee temptation" later in that novel (316). The author's more complete conjuring trick in Shirley, when the mother actually reappears, may say something about her own needs at the time of writing, when Branwell, Emily and Anne Brontë had all died so tragically young, and so soon after one another. Initially it does seem to show her finding vicarious relief in a warm maternal embrace. As Mrs Pryor clasps her daughter, the narrative resonates with images of regression, withdrawal and even constraint:

"... Daughter! we have long been parted: I return now to cherish you again."

She held her to her bosom: she cradled her in her arms: she rocked her softly, as if lulling a young child to sleep.

"My mother! My own mother!"

The offspring nestled to the parent: that parent, feeling the endearment and hearing the appeal, gathered her closer still. She covered her with noiseless kisses: she murmured love over her, like a cushat fostering its young. [410]

Now, Caroline had once claimed to "wish fifty times a-day" to have some kind of employment (235). She had been quite unfazed by the advance of the Dissenters on the way to the Whitsuntide feast at Briarmains, the home of the local manufacturer, Mr. Yorke. She had needed to be held back from helping Robert Moore when he was faced with rioting mill-workers. But here she is reduced to being like a small child again, ready to be lulled to sleep. Mrs Yorke had previously taunted Caroline for seldom putting her nose "over her uncle, the parson's, garden-wall" (389); at this point it seems as if she might never do so again.

As it happened, Lewes, who had been scathing about other parts of the novel, was perfectly delighted by this scene. Typically Victorian in his view of motherhood as the "grand function of woman" (qtd. in Allott 161), and unable to see how Mrs Pryor could have abandoned her child in the first place, he enthused in the Edinburgh Review over the "simple, humble, thrilling naturalness" of the episode, describing it as "one of the most touching and feminine scenes in our literature" (qtd. in Allott 169; emphases added). His near-oxymoron "thrilling naturalness" not only hints at the powerful tension between belief and disbelief which any reader must feel here, but also embodies the powerful prevailing iconography of maternity. But partly, too, it betrays the male critic's satisfaction that Caroline, whose discourse on the "condition of women" had so irked him (see Allott 168), is here reduced to utter dependence.

Yet Lewes was doomed to disappointment after all. The unexpected revelation proves strengthening in the long term. Caroline was very ill before it: the title of this chapter is "The Valley of the Shadow of Death." She herself had said that perhaps an "abundant gush of happiness" might revive her (409), and it does: the emotional fillip she receives here raises her spirits and promotes her long-term recovery. Better still, Mrs Pryor, who admits to her lack of "moral courage" in the past, soon turns out to be empowering. When Caroline murmurs happily, "It seems so natural, mamma, to ask you for this and that. I shall want nobody but you to be near me, or to do anything for me...," the ex-governess responds very sensibly, "You must not depend on me to check you: you must keep guard over yourself" (413). Thus melodrama and sentimentality alike subside, the "sweat of agony" dries off the watching mother's forehead (418), and both Caroline and the narrative take a turn for the better.

After the revelation, Caroline, who "was usually pained to require or receive much attendance" (401), soon begins to regain her physical and mental strength – too soon, in fact, for the original Times reviewer of the novel, who exclaimed irritably: "Mark how Caroline Helstone gets suddenly well after she had been as suddenly carried to the very edge of the grave!" (qtd. in Allott 150). But a mother's love would be a particular and potent blessing for a young woman raised by an unsympathetic uncle, and a matter of weeks after her first "touching endeavour to appear better" (419) she is seen struggling through dangerous fields in "blinding snow and bitter cold" (537), determined to slip in and visit the wounded Robert Moore at Mrs Yorke's house. This is a risky business: young Martin Yorke has to keep three dragons at bay for her – his outspoken mother, Robert's sister Hortense and the great hefty pipe-smoking nurse Zillah Horsfall. In no way, then, does this novelist allow herself to be thoughtlessly carried away without "pausing to attend to so paltry a consideration as artistic unity" (Cecil 116); but nor does she avoid struggling with painful realities. She has her purpose, an important part of which is to ensure that her heroines have a purpose as well.

There is a much more open acknowledgement here that marriage does not inevitably fulfil that purpose. "My dear, romances are pernicious," Mrs Pryor tells Caroline, adding that no marriage can be "wholly happy. Two people can never literally be one" (366). Nothing could be more explicit, or more ominous. Shirley, who had once felt that she might be styled "Shirley Keeldar, Esquire" (213), and who has her own quite considerable means, decided opinions and a strong character, has also been ambivalent about her marriage. Once her own is arranged, to Robert's brother Louis, she is seen to be "fettered to a fixed day ... conquered by love, and bound by a vow" (592; emphases added). She becomes “exquisitely provoking” and even “queer and crazed” (592-23), not because of the mad dog’s bite which she had dealt with so staunchly (though she had worried about that), but as she bows to the yoke of marriage. Like William Crimsworth's in The Professor, her understandable hesitation is overcome — not by the lifting of a strange "spell" but by a completely uncharacteristic desire to be dominated by her future husband. How long might this continue? When the narrator talks of having to "settle accounts" in the last chapter of Shirley (587), the sense of a reluctant yielding to readers' expectations, and more especially of the unfeasibility of long-lasting wedded bliss, is tangible.

Created 20 January 2018