All the illustrations in this short essay are by Fred Barnard, the illustrator of the Household Edition of the novel (1872). Please click on them for larger pictures and more details, and see the bibliography for their source.

ickens had his finger on the pulse of the age when he made the sanctimonious and self-promoting Seth Pecksniff in Martin Chuzzlewit (1844) an architect. In architecture as in other professions, this was an era of increasing professionalisation, when practitioners began to command respect for skills that set them apart from the builders who implemented their designs. Particularly in the cities, where great public buildings and offices were rising in response to civic pride and the country's new global reach, architects were competing for commissions and shouldering huge responsibilities. Their social status rose accordingly, while their reputations rested not only on their artistic vision and professional skill, but on meeting their commitments with integrity. Naturally, as in every walk of life, some practitioners affected to have more of these commodities than they actually possessed.

Seth Pecksniff's "practice"

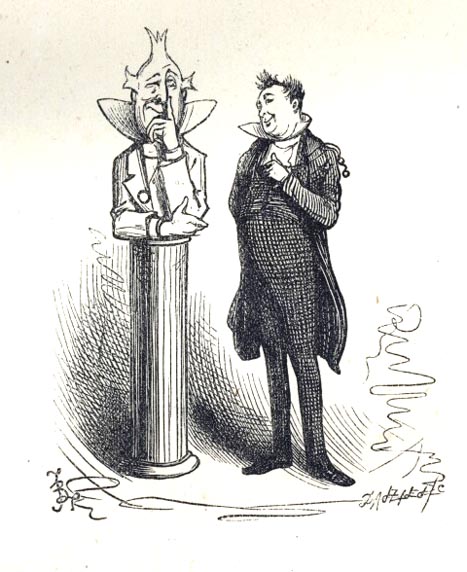

Martin Chuzzlewit may not be one of Dickens's most popular novels, but it is peopled by some of his best-known characters. Thanks in part to its illustrators, Seth Pecksniff is one of these, along with Sairey Gamp, the absurdly garrulous and bibulous nurse/midwife. The former, however, is far more important to the plot. Although the illustration at the right shows him wearing a top hat, he is usually shown, as in the next illustration, with his hair rising in a prominent quiff, because of his mannerism of "rubbing his hair up very stiff upon his head" (122). As for more inward qualities, the most marked is his sanctimoniousness, which this first illustration expresses so perfectly.

It has been remarked that Mr. Pecksniff was a moral man. So he was. Perhaps there never was a more moral man than Mr. Pecksniff: especially in his conversation and correspondence. It was once said of him by a homely admirer, that he had a Fortunatus’s purse of good sentiments in his inside. In this particular he was like the girl in the fairy tale, except that if they were not actual diamonds which fell from his lips, they were the very brightest paste, and shone prodigiously. [10]

Pecksniff's morality is indeed spurious, and Dickens's description of him amounts to a scathing satire on his personal and professional behaviour. This "most exemplary man" has a "soft and oily" manner and presence: "In a word, even his plain black suit, and state of widower, and dangling double eye-glass, all tended to the same purpose, and cried aloud, 'Behold the moral Pecksniff!'" (10). He is often linked with Uriah Heep in David Copperfield (1850), since both are outstanding examples of Dickens's hypocrites (e.g., see Carey 64-65); but Pecksniff presents himself with voluble pretension, rather than with obsequious cringing.

The pretence runs straight through into his chosen occupation. He sells himself constantly:

The brazen plate upon the door (which being Mr. Pecksniff’s, could not lie) bore this inscription, “Pecksniff, Architect,” to which Mr. Pecksniff, on his cards of business, added, “and Land Surveyor.” In one sense, and only one, he may be said to have been a Land Surveyor on a pretty large scale, as an extensive prospect lay stretched out before the windows of his house. Of his architectural doings, nothing was clearly known, except that he had never designed or built anything; but it was generally understood that his knowledge of the science was almost awful in its profundity. [10-11]

If Pecksniff had never "designed or built" anything, we may ask, how could he have made any money? There are at least two answers.

Mr. Pecksniff’s professional engagements, indeed, were almost, if not entirely, confined to the reception of pupils; for the collection of rents, with which pursuit he occasionally varied and relieved his graver toils, can hardly be said to be a strictly architectural employment. His genius lay in ensnaring parents and guardians, and pocketing premiums. A young gentleman’s premium being paid, and the young gentleman come to Mr. Pecksniff’s house, Mr. Pecksniff borrowed his case of mathematical instruments (if silver-mounted or otherwise valuable), entreated him, from that moment, to consider himself one of the family; complimented him highly on his parents or guardians, as the case might be; and turned him loose in a spacious room on the two-pair front; where, in the company of certain drawing-boards, parallel rulers, very stiff-legged compasses, and two, or perhaps three, other young gentlemen, he improved himself, for three or five years, according to his articles, in making elevations of Salisbury Cathedral from every possible point of sight; and in constructing in the air a vast quantity of Castles, Houses of Parliament, and other Public Buildings. Perhaps in no place in the world were so many gorgeous edifices of this class erected as under Mr. Pecksniff's auspices. [11]

Taking a "premium" and "borrowing" valuable instruments are only the beginning. Not all the pupils' works remained "in the air." Even if Pecksniff has never designed or built anything himself, he does have buildings to his name. He maintains his reputation as a practising architect by passing off his pupils' work as his own, justifying this deception by claiming that some small adjustment, that only he could make, was needed to perfect their plans. Besides fees and little extras like fancy compasses, then, another benefit that he derives from his pupils is their talent.

Then there is yet another possibility for exploitation, although it has not succeeded yet. Pecksniff also has his pupils design so many churches that "if but one-twentieth part of the churches which were built in that front room, with one or other of the Miss Pecksniffs at the altar in the act of marrying the architect, could only be made available by the parliamentary commissioners, no more churches would be wanted for at least five centuries" (11). The implication here is that Pecksniff has been trying to marry off his grown-up daughters, Charity and Mercy, to promising pupils.

At the beginning, one of Pecksniff's pupils, John Westlock, has just fallen out with him. Realising how little, if anything, he has received in return for his fees, and how much he has been exploited, John is leaving in high dudgeon. His replacement is about to arrive.

The initiation of the new pupil

Pecksniff hopes to get much more out of this pupil than from his former one. His big goal is not the premium, which indeed he has waived, to the great surprise of his daughters. Nor does he take young Martin Chuzzlewit on because of his architectural promise, although he proves to be surprisingly gifted, and Pecksniff will take full advantage of that later on. What Pecksniff has his eye on at this point is considerably more important: the fortune that Martin's grandfather (a bitter old gentleman of the same name, who is also Pecksniff's cousin) is expected to leave. Thus the third possible method of exploitation seems the most hopeful — that he might find his way to Martin's grandfather's wealth, possibly through a family alliance. If this were to happen, the gain could be more than ordinarily worthwhile.

The path to such a goal is, however, exceedingly tricky. For one thing, Martin is currently out of favour with his grandfather. For another, Charity and Mercy are as superficial, affected and grasping as their father, in their own ways. The inappropriately named Charity is bad-tempered, too. Moreover, Martin's heart is already given to his grandfather's young companion, the sweet-natured orphan, Mary Graham. Worse still, the whole family inheritance lottery is stacked against him because of old Martin's suspicious nature, and other schemers in the family, notably young Martin's dastardly, even murderous, uncle Jonas Chuzzlewit. Jonas's involvement in a swindling insurance company will provide yet more (and more melodramatic) complications in the later part of the novel. The last work of Dickens's earlier picaresque period, this novel's plot is so tangled that it is hard to keep track of it.

Besides its inherent interest, the story of the scheming architect, and his despicable professional misconduct, turns out to be a useful thread to follow. Most of the details about Pecksniff's profession come at the beginning. Showing Martin round his house for the first time, he boasts of offering "the best practical architectural education" (12) to his trainees, displaying all the signs of his exalted position and engagement in professional matters, with obviously mock humility. One such sign is the bust that the frontispiece illustration shows him standing beside: "This," he says, "opening another door, 'is the little chamber in which my works (slight things at best) have been concocted. Portrait of myself by Spiller. Bust by Spoker. The latter is considered a good likeness. I seem to recognise something about the left-hand comer of the nose, myself....'” Pecksniff continues by drawing Martin's attention to his stock of architectural books and other architectural aides:

“Various books you observe,” said Mr. Pecksniff, waving his hand towards the wall, “connected with our pursuit. I have scribbled myself, but have not yet published. Be careful how you come up stairs. This,” opening another door, “is my chamber. I read here when the family suppose I have retired to rest. Sometimes I injure my health, rather more than I can quite justify to myself, by doing so; but art is long and time is short. Every facility you see for jotting down crude notions, even here.”

These latter words were explained by his pointing to a small round table on which were a lamp, divers sheets of paper, a piece of India rubber, and a case of instruments: all put ready, in case an architectural idea should come into Mr. Pecksniff’s head in the night; in which event he would instantly leap out of bed, and fix it for ever. [61-62]

Moving on, he takes credit for bringing out his pupils' potential: “'This,' said Mr. Pecksniff, throwing wide the door of the memorable two-pair front; 'is a room where some talent has been developed, I believe, This is a room in which an idea for a steeple occurred to me, that I may one day give to the world. We work here, my dear Martin. Some architects have been bred in this room: a few, I think, Mr. Pinch?'” (62). Tom Pinch, the thoroughly good-natured ex-pupil whom he shamefully exploits as a general dogsbody, but who is so truly virtuous and kind himself that he has yet to see through him, backs him up, allowing Pecksniff to expatiate on the work produced under his auspices:

“You see,” said Mr. Pecksniff, passing the candle rapidly from roll to roll of paper, “some traces of our doings here. Salisbury Cathedral from the north. From the south. From the east. From the west. From the south-east. From the nor’-west. A bridge. An alms-house. A jail. A church. A powder-magazine. A wine-cellar. A portico. A summer-house. An ice-house. Plans, elevations, sections, every kind of thing...." [62]

Pecksniff's modus operandi is then exposed in some detail. As it happens, he explains to Martin, he and his daughters are about to go off to London. He has business there. (This seems to consist in scouting for new recruits: he tells Mrs Todgers, the landlady at their boarding house, to look out for "an orphan with three or four hundred pound" [115]. He will also try to ingratiate himself with the rich family that employs Tom's sister Ruth Pinch as a governess.) In the meantime, however, he suggests some occupation for Martin. He starts by proposing some distinctly unappealing projects: "'Suppose you were to give me your idea of a monument to a Lord Mayor of London; or a tomb for a sheriff; or your notion of a cow-house to be erected in a nobleman’s park. Do you know, now,' said Mr. Pecksniff, folding his hands, and looking at his young relation with an air of pensive interest, 'that I should very much like to see your notion of a cow-house?'” Inevitably, Martin appears to be rather unimpressed by these projects. Still, Pecksniff persists. “'A pump,' said Mr. Pecksniff, 'is very chaste practice. I have found that a lamp-post is calculated to refine the mind and give it a classical tendency. An ornamental turnpike has a remarkable effect upon the imagination. What do you say to beginning with an ornamental turnpike?'” (67). When Matin continues to look doubtful, another idea seems to strike the architect quite accidentally:

“Stay,” said that gentleman. Come! as you’re ambitious, and are a very neat draughtsman, you shall — ha ha ! — you shall try your hand on these proposals for a grammar-school: regulating your plan, of course, by the printed particulars. Upon my word, now,” said Mr. Pecksniff, merrily, “I shall be very curious to see what you make of the grammar-school. Who knows but a young man of your taste might hit upon something, impracticable and unlikely in itself, but which I could put into shape? For it really is, my dear Martin, it really is in the finishing touches alone, that great experience and long study in these matters tell. Ha, ha, Now it really will be,” continued Mr. Pecksniff, clapping his young friend on the back in his droll humour, “an amusement to me, to see what you make of the grammar-school.” [67]

Martin accepts this much more interesting task, and Pecksniff provides him with all necessary materials,

dwelling meanwhile on the magical effect of a few finishing touches from the hand of a master; which, indeed, as some people said (and these were the old enemies again!) was unquestionably very surprising, and almost miraculous; as there were cases on record in which the masterly introduction of an additional back window, or a kitchen door, or half-a-dozen steps, or even a water spout, had made the design of a pupil Mr. Pecksniff’s own work, and had brought substantial rewards into that gentleman’s pocket. But such is the magic of genius, which changes all it handles into gold! [67]

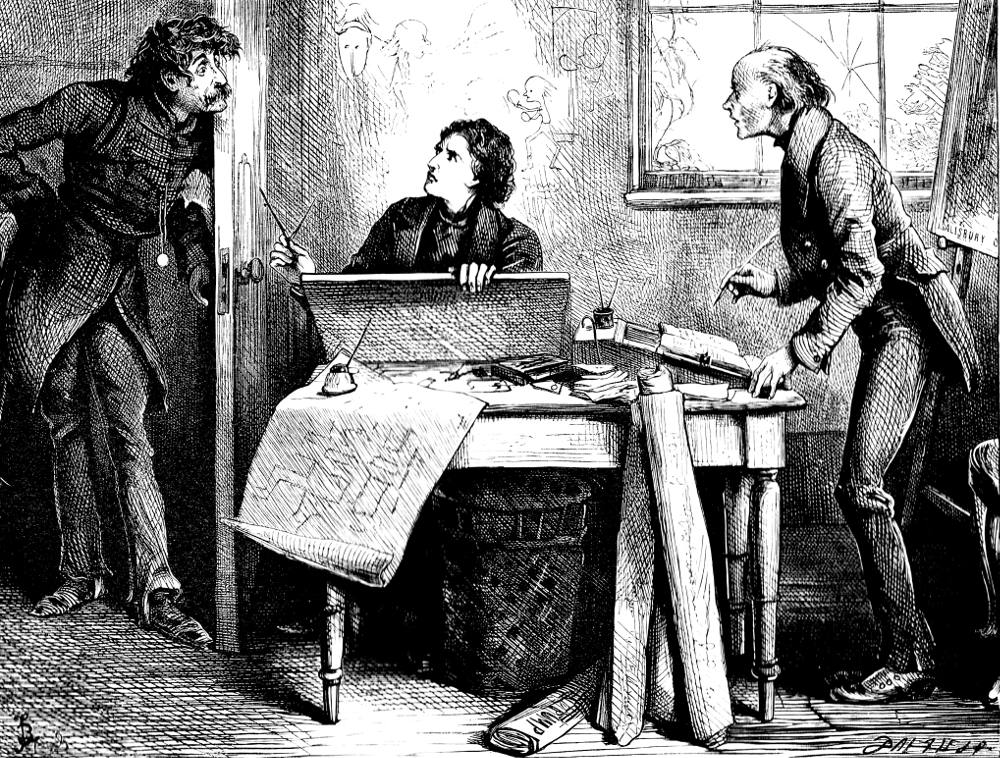

Thus, when Montague Tigg (later known as Tigg Montague) makes his first appearance, he finds Martin and Tom Pinch hard at work the next afternoon, in Pecksniff's absence, with Martin already well advanced in his plans for the grammar school — as shown in the illustration on the right.

A young architect's setbacks

The plans are soon forgotten in the turmoil that follows. Mr Pecksniff's dismissal of Martin, at the behest of the the elder Chuzzlewit, is followed by a long episode in which Martin, together with Mark Tapley from the Blue Dragon inn, attempts to make his fortune in America. Dickens's own experiences in that part of the world, during his tour of January-June 1842, were fresh in his mind when he started writing the novel in the November of that year, and his distaste for American brashness colours the episode. Far from making his fortune, Martin fares worse here than at Pecksniff's. Duped into buying land in a place misleadingly called Eden, he (or, rather, the faithful Mark on his behalf) tries his best, setting up shop as "Chuzzlewit & Co., Architects and Surveyors." His architectural instruments are put on display in front of their hut, with the compasses stuck "upright in a stump before the door" (287). But these pathetic endeavours prove futile in the muddy swamp with which they are surrounded: the prospective orders never materialise.

The whole trip is traumatic. Martin almost dies from the fever contracted in the unwholesome air of the settlement. Mark, seen here sitting beside his rough bed, nurses him tenderly through it. Despite his own determined cheerfulness, Mark too suffers greatly there. Fortunately, his selflessnss is not lost on Martin, and the experience has the good effect of changing his character for the better, and making him more considerate of others' feelings and well-being.

Only on their return to London, after this long and testing diversion, does the would-be architect's work on the grammar school resurface. It does so, like much else in the narrative, by a strange coincidence. The two young men just happen to spot Pecksniff passing by on the street with architectural plans under his arm. Their curiosity piqued, they follow him, only to find that he is laying the foundation stone of a grammar school to the very design that Martin had drawn up — except for the addition of four windows, which, in Martin's judgement, entirely spoil the original plan. After all he has been through in America, here is Martin's one piece of good work in England being misappropriated by Pecksniff — who is, of course, receiving all the credit for it. It tests credulity that Martin's plan as a raw pupil should have won Pecksniff the commission for the school, but here again readers are expected to suspend their disbelief.

The collapse of an edifice

Pecksniff's public unmasking at the end is not due to this incident, but to the elder Martin Chuzzlewit's close observation of him. Having for some time cast himself on Pecksniff's hospitality in order to fathom his true nature, the old man has come to a full realisation of his cousin's faults. Far from providing him with any fortune, he smites the architect with his stick, so that he topples over. Pecksniff also falls in other respects: lured by Jonas, he has lost his money to the fraudulent insurance company.

That his faults have expressed themselves in his professional life has helped to round out an otherwise totally one-dimensional character and make him somewhat more credible. What ought indeed to be "a not dishonourable or useless career" (508) is one to which he has brought no gifts of his own, but only his engrained propensities for money-grubbing, deceit and pretension. As suggested above, the architectural element in the narrative has also served to hold the eye amid the shifting scenes of its tangled structure, in which many more characters play a part than have been introduced here.

Future prospects

As for Pecksniff's pupils, they will find their rewards not only in their personal lives but in their professional ones as well. John Westlock urges Martin to write and claim the grammar school design as his own, clearly with a view to advancing him in his career. Restored to favour with his grandfather, and able to plan his future with Mary Graham, Martin will hardly need the money but will no doubt wish to have an occupation. And at the end, when John falls in love with Ruth Pinch, now released from her uncongenial post as governess, he is able to tell her that he himself has got a "capital opportunity for establishing himself in his old profession in the country" (611). There, he says, Tom will make the perfect assistant for him. It is not all joy for Tom, who has long carried in his heart an unrequited love for Mary, and will continue to do so; but at least brother and sister will not need to be separated. In this way, he is not entirely left out of the happy ending, and indeed contributes to it with his usual good nature, and his gifts as an organist.

Dickens and architecture

Does Dickens's delineation of Pecksniff suggests that he had a spite against architects? It seems unlikely. After all, he had great respect for his good friend and brother-in-law, the architect Henry Austin (see Forster III: 262), and was acquainted with other architects, including at least two eminent ones, Charles Barry of Palace of Westminster fame (see Letters VI: 296, n.5), and Philip Hardwick (see Letters VI: 626). On the other hand, in the spring of 1851, he would express doubt about the iron-and-glass structure of Crystal Palace, saying that the civil engineers would look bad if it collapsed (see Letters VI: 296). Steven Connor also finds a "mistrust" of architects in Dickens's advice to his philanthropic friend, Angela Burdett-Coutts, in March 1852, about seeking second opinions before embarking on one of her building projects (178) — although the concern here is simply with the proper provision of "sanitary arrangements" (Letters VI: 626-27), and one of the experts he recommends to her is his trustworthy brother-in-law.

Dickens did, of course, dislike the industrial structures of his age, as seen later, for example, in the description of Coketown in Hard Times (1854), with its grime-coated red brick, vile smoking chimneys and everlastingly rattling machinery. In this connection, David Spurr is surely right to talk of his "pre-modern sense of estrangement from the modern world" (84). But the built environments featured in Martin Chuzzlewit are not of these types, and in fact we see Tom Pinch brimming with admiration for "church steeples, and other public buildings" (461) on the way from the Inns of Court to Islington.

Most probably, then, Dickens simply hit on the idea of making Pecksniff an architect by some chance association. Once having settled on it, he proceeded to capitalise on his choice in his own inimitable way, educating the general public as only he could, by exposing to ridicule some of the abuses associated with it.

Perhaps Dickens also used references to architecture to create an underlying pattern in the novel. The profession is, to be sure, a good source of analogies. When it comes to Pecksniff himself, here is a man who is all façade, without foundations; a man who, like Montague, tries to build his fortune "on the weaknesses of mankind" (509); and a man whose final demolition proves peculiarly satisfying. The analogy of building also works well in another respect. As a positive alternative to such a figure, what is needed is the construction of the truly moral self, not just the front elevation, as in Pecksniff's case, but the solid substance of it. Both the Martin Chuzzlewits, grandfather and grandson, undergo this process successfully, learning to excise their selfishness and adopt a fresh attitude to life and to others. These were relatively early days for Dickens, and it is doubtful that he was exploiting these symbolic possibilities in any sustained manner. Yet that is the way his work was going, and he might indeed have been beginning to explore them.

By the end the younger Martin has been cured of "building castles in the air" (205) — or trying to build them on a muddy swamp. After being "disciplined in a rough school" (499), especially by his experiences in America, and united at last with the woman he loves, he now has a bright future ahead of him. Dickens gives no further details about the professional careers of either of the two young architects. But we can guess that whatever they go on to build will be based on firm foundations.

Bibliography

Carey, John. The Violent Effigy: A Study of Dickens' Imagination. London: Faber, 1973.

Connor, Steven. "Babel Unbuilding: The Anit-Archi-Rhetoric of Martin Chuzzlewit." Dickens Re-Figured: Bodies, Desires, and Other Histories. Ed. John Schad. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1996. 178-199.

Dickens, Charles. The Letters of Charles Dickens, 1850-1852. Vol. VI. Eds. Graham Storey, Kathleen Tillotson and Nina Burgis. Pilgrim ed. Oxford: Oxford University, 1988.

_____. The Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit. London: Chapman and Hall, 1844. Internet Archive. Contributed by the University of California Libraries. Web. 6 December 2018.

_____. The Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit, with 59 illustrations by Fred Barnard. Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1872. [Shown above is the front cover of the copy from which our contributing editor Philip Allingham scanned these illustrations. It was a gift to him from George Gorniak, publishing editor of The Dickens Magazine.]

Forster, John. The Life of Charles Dickens. Vol. 3. Philapdelphia: Lippincott, 1874. Internet Archive. Contributed by the New York Public Library. Web. 6 December 2018.

John, Juliet. Dickens's Villains: Melodrama, Character, Popular Culture. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001.

Spurr, David. Architecture and Modern Literature. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2012.

Created 2 December 2018