Left: Sol Eytinge, Jr.'s portrait drawing of Dickens. Right: An 1867 photograph of Dickens by J. Gurney & Sons. [Click on thumbnail for larger image.]

It was my privilege, many years ago, to clasp the hand of Charles Dickens and to hear from his lips the cordial assurance of his personal regard. "If you come to England," he said, "be sure to come to me; and it won't be my fault if you don't have a good time."' The great novelist said those words as we sat together aboard a little tug-boat, on the morning of April 22, 1868, steaming to the Russia, which was anchored in the bay of New York, and about to sail for England. It was a lovely morning. The air was genial, the broad expanse of the Hudson and the bay sparkled in brilliant sunlight, and the whole silver scene was vital with motion and cheerful sound. Dickens had expressed the wish to slip away unimpeded by a crowd, for his many' Readings, together with much travel and continuous social exertion, had taxed his endurance and he [181/182] was weary and ill. Accordingly, accompanied by his friend and manager, George Dolby', he drove from his hotel, the Westminster, to the pier at the western end of Spring Street, where a few friends were to meet him and embark with him for the steamship. The party included James T. Fields, James R. Osgood, Sol Eytinge, Jr., A. V. S. Anthony, H. C. Jarrett, H. D. Palmer, George Dolby, and the present writer, — who is the sole survivor of that group. When Dickens alighted from the carriage and glanced at the river he uttered the joyous exclamation: "That's home!" We were soon aboard the tug-boat, — called "The Only Son," — and as we sailed down the river it pleased the novelist to talk with me about many things. I had heard all his Readings in New York, and had written about them, and on that subject he had many pleasant words to say. Mention being made of the English poet Matthew Arnold, he spoke warmly, saying: "He is one of the gentlest and most earnest of men." Of the renowned foreign actor Charles Fechter, — who had not visited America, but was soon to come — he said: "When you see [182/183] Fechter you will, I think, recognize a great artist." So the talk rambled on, till presently, I ventured to speak of the benefit and comfort that I, in common with thousands of other readers, had derived from his novels. My favorite, in those days, was "A Tale of Two Cities," and in a fervor of enthusiasm I declared to him the opinion that it is the greatest of his works. He seemed much pleased, and he answered, with evident conviction: "I think so too!" Study and thought, in years that since have passed, convince me that we were both somewhat mistaken, for the indisputable supremacy of Dickens is that of the humorist, and surely the foremost of his novels, in respect of humor, are "David Copperfield" and "Martin Chuzzlewit," but the avowal he then made affords an interesting glimpse of his mind, and therefore it is worthy to be remembered.

The humorist not infrequently undervalues his special gift, and fancies himself to be stronger in pathos than in mirth. Dickens, as shown by many denotements in his writings, was fond of melodrama, meaning the drama of astonishing [183/184] situations, — a branch of art by no means to be despised, but not the highest, — and he liked positive, literal effects rather than suggestions to the imagination: it is known, for example, that he ranked the performance of Solon Shingle by John E. Owens, which was reality, above the performance of Rip Van Winkle, by Joseph Jefferson, which, in that actor's treatment of it, was poetry. No critical considerations, however, affected our discourse, in the conversation that is now recalled. The novelist had labored through a toilsome season: his work was done, his mind was at ease, and he was blithe in spirits, — only subdued, at moments, by consciousness of impending separation from dear friends. There was about him the irresistible charm of ingenuous demeanor and absolute simplicity. His appearance, that day, afforded a striking contrast with the appearance he had presented at the reading desk. When before an audience Dickens assumed the pose of an actor. He wore evening dress, but he used the accessories of foot-lights and also a colored screen as a background, and he "made up" his face, as actors do. There [184/185] was, in his reading an extraordinary facility of impersonation, and he employed all essential means to heighten the desired effect of it. Now he was himself. The actor had disappeared. The man was with us, unsophisticated and unadorned. He wore a rough travelling suit and a soft felt hat; his right foot was wrapped in black silk, for he had been suffering from gout; and he carried a plain stick. After he had boarded the steamship, and while he was talking with the captain and other officers, the members of our little party assembled in the saloon with what he afterward jocosely described as "bitter beer intentions." Soon he approached our group and, addressing me, he said: "What are you drinking?" I named the fluid, and, responding to his request, filled a tumbler for him. He shook hands with us, all around, with a grasp of iron, emptied his glass, put it on the table, and turned to greet the old statesman Thurlow Weed, who had just then arrived: whereupon, immediately, I seized that glass, and, to the consternation of the attendant steward, put it into my pocket, — mentioning, as I did so, Sir Walter Scott's [185/186] appropriation of the glass of King George IV, at the civic feast in Edinburgh, long ago. The royal souvenir, it is recorded, fared ill, for Sir Walter sat upon it and broke it. The Dickens souvenir survives and is still in my possession. When the farewells had been spoken and we had left the ship, Dickens stood at the rail, his brilliant eyes (and surely no eyes more brilliant were ever seen) suffused with tears, and, placing his hat on the end of his stick, he waved it to us till distance had hidden him from view. I never saw him again.

The Poets' Corner of Westminster Abbey [Not in original text; click on thumbnail for larger image.]

Nine years later, in 1877, when I first went to England, though I could not seek for him at his home, I stood with reverence beside his grave. He rests in the Poets' Corner of Westminster Abbey. As I drew near to that sacred spot I saw a single red rose lying on the pavement that bears his name, and almost at the instant a heedless visitor, indolently strolling along the transept, trod upon the flower and crushed it.

The general heart of mankind was touched by Charles Dickens. Criticism, in its examination of his writings, may refine and discriminate to [186/187] the utmost possible extent, but it cannot obliterate that solid, decisive truth. His own words tersely and convincingly declare the consummate, conquering principles of his faith and his works:

Ages of incessant labor, by immortal creatures, for this earth, must pass into eternity, before the good of which it is susceptible is all developed. Any Christian spirit, working kindly in its little sphere, whatever it may be, will find its mortal life too short for its vast means of usefulness. There is nothing in the world so inevitably contagious as laughter and good humor.

Upon those principles Dickens continuously acted, and in his literary life, of more than thirty years of conscientious labor, he created enduring works of art, — peopling the realm of pure fiction with a wide variety of characters, interpreting human nature in manifold phases, reflecting the passing hour, demolishing social abuses, teaching the sacred duty of charity, comforting and helping the poor, and stretching forth the hands of loving sympathy to the outcast and the wretched. Thus laboring, he enriched the world with a perpetual spring of kindness, of hope, and of innocent, happy laughter; he inculcated devotion to [187/188] noble ideals; and he stimulated and — strengthened the spiritual instincts of the human race. Any relic of such a man is precious, and the Dickens souvenir to which I have adverted, — the glass from which he took his parting drink, on the day of his final departure from America, — has been tenderly cherished. Once in a while it is brought forth and shown, for the pleasure of a literary visitor. On one occasion of exceptional and peculiar interest, when Charles Dickens, the younger, dined with us in our home, March 3, 1883, it was placed in his hands, and thus, after the lapse of fifteen years, the fare well glass of the illustrious father was touched by the lips of the reverent and honored son.

Gad's Hill [Click on thumbnail for larger image.]

The younger Charles Dickens, a man of uncommon talents and of a singularly amiable and winning personality, possessed abundant and deeply interesting recollections of his father, and, naturally, he was fond of talking about him. Adverting to his father's Readings, he mentioned several picturesque and significant incidents, all tending to show the deep interest that the great novelist felt in that branch of his art, [188/189] and the scrupulous care with which he trained himself for the vocation of public reader. The home of Dickens, Gad's Hill Place, a house that he had known and fancied when a boy, and that he bought in 1856, is near to Rochester and Chatham, where there is a military and naval establishment. "Noisy brawls sometimes occurred in the neighborhood," said the younger Dickens, "but we did not regard them. One morning I heard a great din, shouts and screams, as of a violent, drunken quarrel. At first I did not heed it, but after a while, as it steadily continued, I went out to our grove, across the road, where I found my father, alone. 'Have you heard the row?' I asked. 'Did you hear any noise?' he answered. 'Yes,' I replied, 'I thought somebody was being killed. What can hare happened? Did you shout?' 'I made the row,' he replied; ' I have been rehearsing the murder scene in "Oliver Twist." It was the wrangle of Bill Sykes and Nancy that you heard; I have just been trying to kill Nancy.' 'Well, I said, 'I should think you have succeeded, for a more damnable racket was never made."' The ear- [189/190] nest narrator proceeded to tell me that his father was warned against the prodigious exertion necessitated by those Readings of his, and especially the reading from "Oliver Twist." The death of Dickens (aged only fifty-eight) was precipitated by his implication in a frightful rail-road accident, which occurred at Staplehurst, a year before he died, but, undoubtedly, the efforts that he made as a public reader hastened the close of his great career. Indeed, toward the last, his son Charles, acting in obedience to the imperative order of his father's doctor, invariably sat in front, near to the stage, and, — as he told me, — had, privately, provided himself with a short ladder, by means of which he could obtain immediate access to the platform, in order to aid his father in case he should be smitten with a stroke of apoplexy. Such an end was expected, and such was the end that came; but, happily, not in public. Dickens gave his last reading on March 19, 1869, at St. James's Hall, London. He died, suddenly, of apoplexy, in his dining room at Gad's Hill Place, June 9, 1870. The younger Charles Dickens long survived his father, dying on July [189/190] 21, 1896, — and so one of the kindest men, one of the gentlest spirits, one of the best speakers in England, vanished from our mortal scene.

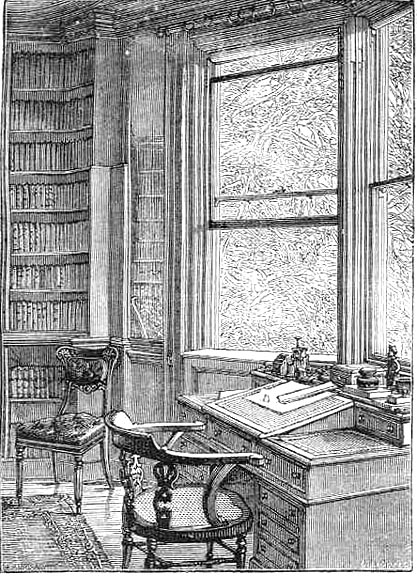

Dickens's study at Gad's Hill [Click on thumbnail for larger image.]

The name of the Dickens house and of its locality is spelled both ways — Gad's Hill and Gads-hill. In the second act of the First Part of Shakespeare's great play of "Henry IV", it is spelled Gadshill, and it is used as the name of a place and as the name of a person, — the servant of Falstaff. The place is westward from Rochester. On a brilliant day in the summer of 1885 I made a pilgrimage to that literary shrine, — driving from the Bull, at Rochester, Mr. Pickwick's tavern, and passing many hours among the haunts of Dickens. There is, or was, a quaint little inn, called the Falstaff, near to Gad's Hill Place, on the opposite side of the turnpike road, and from that resort I dispatched a card to the owner of the mansion, Major ——, signifying that one of the American friends of Dickens would gratefully appreciate the privilege of viewing the house. The Major received me with cordial hospitality, and so it happened that a stranger spoke, upon the threshold of Dickens, [191/192] the welcome that the great author himself intended and promised to speak. There was the study, unchanged, — the room in which "Great Expectations," "Our Mutual Friend" and "Edwin Drood" were written; there was the [192/193] writing-desk at which the magician would never sit again; there was the vacant chair; there, on the back of the door, was the painted book-case, with the mock volumes, bearing comic titles, invented by the novelist; and over all the golden summer sunshine glimmered and a magic light of memory that words are powerless to paint. I sat in the chair of Charles Dickens and reverently wrote my name in the chronicle of pilgrims to his earthly home. The dining room had, on that day, been prepared for a banquet for many persons, but no guests had yet arrived, and the Major kindly permitted me to enter it and see the sofa on which Dickens died; and later he conducted me through a tunnel underneath the road, giving access to a field and grove where was the Swiss chalet presented to Dickens by friends of his in Switzerland, a snug retreat to which he often resorted to escape interruption when at work, and where he passed his last day as a living man. I recalled his words, as I stood there: "If you come to England be sure to come to me," and it seemed to me that he was actually present, and that I felt again the hearty grip of his hand and heard the ringing tones of his cheery voice. The garden, was gay with red roses. "Dickens loved these," said the Major, and, so saying, he placed a cluster of them in my hands, by way of gracious farewell.

The Readings of Dickens

Dickens was not only an excellent reader but a good actor. The discerning reader of his novels perceives that he possessed a keen dramatic instinct. The auditor of his Readings was soon convinced that he also possessed a positive dramatic faculty. In reading scenes from his novels he entered into characters that he had created, and his correct assumption of diverse personalities was decisively effective. Now he was Scrooge; presently Mr. Fizgig; then Bob Cratchitt; and by and by he passed, easily, by the expedient of artistic suggestion, — and by [193/194] something more, which is difficult to define, — through the contrasted guises of Serjeant Buzfuz, the little Judge, Mrs. Cluppins, Sam' Weller, Mr. Winkle, Micawber, Pecksniff , and Sairey Gamp. The skill that merges personality with a fictitious character, and yet does not efface the performer's individual quality, is indispensable in acting. Dickens possessed it. He knew the effect that he wished to produce. His method was characterized by simplicity and delicacy. In the copious, mellow, musical vocalism (a little marred by the monotony of rising inflection), the authoritative manner, the unaffected, free gesticulation, and the spontaneous accordance of the action with the word the authentic art of the actor was conspicuous. As an interpreter of tragic character and feeling he was consistent and often impressive, as in his reading of the storm chapter, much condensed, in "David Copperfield," — that wonderful blending of the terrors of the tempest with the tragic and pathetic culminations of human fate, — but he was, distinctively, a humorist, and his humorous embodiments, for embodiments, practically, they were, [194/195] and not merely denotements, were his indubitable triumphs of dramatic art. In outbursts of passionate emotion, while he did not lack fervor, he lacked vocal power; but the moment he entered. the realm of humor he was a monarch. His whole being then seemed aroused. His clear, brilliant, expressive eyes twinkled with joy; his countenance expressed bubbling mirth that was with difficulty restrained; his tones grew deep and rich; he, manifestly, escaped from all consciousness of self; and he completely captivated his auditor.

At this distance of time, — forty years having passed since last I heard his voice, — it is not easy to name his superlative comic achievements; but my clearest remembrance of them would specify Micawber, Mrs. Gamp, Sam Weller, Mrs. Raddles, Pecksniff, Mrs. Gummidge and the little servant of Bob Sawyer as gems of his humorous acting. There was a sweet, gentle strain of humor in his exposition of the delicate episode of poor little Dora Spenlow; but the scenes in which he revelled and greatly excelled were such as display the festival with Micawber at Canter- [195/196] bury; the supper with Bob Sawyer, in the lodging-house of the shrill, spiteful Mrs. Raddles; and the tipsy altercation between Mrs. Gamp and Mrs. Prig. His finest impersonations, — finest, because of the dramatic interpreter's absolute fidelity to the author's designs, and also because of their integral revealment of his genius, — were, as I remember them, those of Dr. Marigold, and Mrs. Gamp. The latter portrayal was a consummate type of his humor; the former of his pathos. That fat, fussy heathen, that prodigy of eccentric, comic selfishness, that ungainly, sagacious, piggish cockney, Mrs. Gamp, — herself possessing no perception, however slight, of either good feeling or mirth, — delights by the grotesque comicality of a character, both serious and ludicrous, which is skillfully developed and displayed under ingeniously humorous conditions. All lovers of broad fun have rejoiced in Sairey, — in her copious loquacity, her store of anecdote, her appropriate aphorisms, her belief in the utility of regular habits, her talent for sarcasm, her partiality for gin, her naive suggestion of "a bottle on the chimbley-piece, to set to my [196/197] lips when so dispoged," her ample resources of unconsciously ludicrous illustration, her fecund, inexhaustible vocabulary, her mythical friend Mrs. Harris, her formidable compatriot Betsey Prig, and her ever memorable quarrel with that audacious associate. Dickens must have rejoiced in creating Mrs. Gamp, for he evinced the keenest artistic enjoyment in depicting her, — his portrayal of her exemplify.ing absolute harmony between the imaginative ideal and the executive intellectual purpose. Our stage was adorned, in old times, by three comedians, George Holland, William Davidge, and Marie Wilkins, any of whom could have personated Mrs. Gamp perfectly well; but none of them, though aided by the accessories of costume and scenery, could have made the character more actual to the material vision than Dickens made it to the eyes of the mind. He read it, and, at the same time, he contrived to act it.

The same felicity of achievement was perceptible in the portrayal of Dr. Marigold. No other one of his Readings contained more — if so much — of himself. In whatsoever way interpreted, [197/198] the story of Dr. Marigold would touch the heart. As interpreted by Dickens, its harmony of humor and pathos as irresistible. The sketch itself is exceptionally representative of the essential characteristic of its author's genius — vital humanity. No writer has shown himself more capable than Dickens was of pointing those afflicting contrasts which reveal human nature as, at times, so noble, and social conditions as, at times, so tragic. No writer ever was more quick to see or more expert to show the heart that beats beneath the motley, and, therewithal, the masquerade of living, in which so many human beings, of fine feeling and high motive, are doomed to participate,-— often through many arid years of smiling endurance. When Dickens assumed Dr. Marigold, the formal English gentleman, in evening dress, seemed to disappear, while in his place stood the coarsely clad, loquacious pedler, on the footboard of his Cheap-Jack cart, — his dying daughter clasped to his breast, her arms around his neck, her head drooping on his shoulder, — vending his wares — voluble, facetious, resolute — hiding his sorrow — the veritable incarnation of heroism — even while [198/199] the gray shadow of death was stealing over the face of his child. It was an inexpressibly pathetic presentment of dramatic contrast: on one side, self-abnegation, the celestial element of human nature; on the other side, innocent, helpless, forlorn childhood, made doubly sacred by misfortune. I have seen all the important acting that has been shown on the American stage within a past of more than fifty years: I have seen but little in the serio-comic vein, that was better than that of Charles Dickens in the character of Dr. Marigold. This humble tribute can suggest only the general character of his art. His Readings were the spontaneous expression, wisely guided, of a great nature, in the maturity of its greatness, and those persons who heard them enjoyed a precious privilege, never to be forgotten.

Contemporary interest in those Readings, no doubt, was intensified by admiration, — then very general, — of the reader's writings; and perhaps, by reason of that admiration, they seem, in remembrance, to have been finer than they actually were. I do not, however, credit that conjecture. I recall, even now, the action of Dickens [199/200] when, as Bob Cratchitt, he seemed to be throwing a kiss to Tiny Tim, and brushing away a tear, as he prepared to propose the health of Scrooge. Those persons only who hare children and fear to lose them, or, losing them, have lost them, could understand how much that simple action meant. I recall his sad tones and direct way when, as Pegotty, he told of the weary search for Little Em'ly, and " the fine, massive grandeur in his face" when he spoke those touching words: "And only God knows how good them mothers was to me." I remember the exalted, awe-stricken expression of his countenance when, as he closed his narrative of the storm, in "Copperfield," he spoke of the dead man, whose name is unmentioned, and the pathetic tone in which he said: "I saw him lying with his head upon his arm, as I had often seen him lie at school." Those indescribably beautiful strokes of art, and many like them, denoted a consummate artist. It is not, however, to be questioned that the intrinsic power and authentic supremacy of Dickens consisted in authorship, and not in the histrionic illustration of it. He enriched litera- [200/201] ture with creations that can never perish. Humor and pathos blend in his works and make an exquisite music. The geniality of Christmas is nowhere so fully expressed as in "Pickwick" and the "Carol," — here great fires blaze upon spacious hearths, and bright eyes sparkle, and merry bells ring, and sunshine, starlight, and joy make a delicious atmosphere of comfort, kindness, and ardent good-will. There is no terror more ghastly than that on the face of Jonas Chuzzlewit as he breaks out of the woods, after doing the murder. There is no written tempest more actual and terrible than the tempest in which Ham and Steerforth go to their death. There is no emblem of self-sacrifice more sublime than the figure of Sidney Carton at the guillotine. But it is only a glimpse of a great author that is here intended,-— not a critical estimate of works long since accepted into the sacrarium of English Literature. The world knows them by heart, and the judgment of the most exacting of human intellect has recognized and celebrated the scope and the opulence of their writer's genius: the vitality of his thought; the sincerity of his [201/202] virtuous emotion; the certainty of his intuition; the felicity of his inventive skill; the rosy glow of his copious, captivating humor; the fineness of his perception of tragic and comic contrast in human experience; the depth of his sympathy with the common joys and sorrows of the human race; the eloquence of his fluent, nervous, forcible, convincing style; and the profound, steadfast, consistent purpose of his life and his art to inculcate the religion of charity and love. The world is happier and better because Charles Dickens has lived in it.

Reference

Winter, William. "Charles Dickens." Old Friends: Being Literary Recollections of Other Days. New York: Moffat, Yard, & Co., 1909. Pp. 182-202.

Last modified 2 January 2024