[All images are reproduced courtesy of the Warwickshire County Council. — Simon Cooke]

One of the fascinating and frustrating things about writing on George Eliot’s thinking about ethics is how lightly she wears her immense reading in moral philosophy. To many readers, Eliot is famously discursive, throwing in long meditations on ethical issues here, there, and everywhere. But to those of us interested in making sense of her views, those passages can be maddeningly elusive because they don’t cite their sources. Is Eliot’s thinking about sympathy a product of her engagement with Adam Smith, or is it more of a Ludwig Feuerbach thing, or is her reaction to Auguste Comte really the key intellectual generator? Clearly all three inform her thinking, but each is a very different thinker, and what one thinks about Eliot's account of sympathy depends significantly on which writer one takes her to be engaging in a given passage.

One particular example of this problem I’ve thought a lot about is Eliot’s analysis of egoism. Very early on in my decade-long encounter with her work, it struck me that Eliot used the story of her developing egoists to offer an account of what Christine Korsgaard calls ‘the sources of normativity’—an explanation of why and how moral laws have the capacity to obligate us. Egoists after all are meta-ethical challenges in and of themselves: they are living the skepticism of morality philosophers are trying to address. And so stories about egoists often touch on questions about the justifications of morality. Eliot in particular often (though crucially not always) represents egoism as a developmental stage, and what her egoists mature into involves discovering the normativity of morality. The growing egoist in Eliot’s narratives experiences various frustrations and ultimately overcomes those frustrations only through the recognition of the moral importance of other people.

Thus it seemed to me that the various iterations of this narrative arc, which comprise a major part of Eliot’s contribution to the bildungsroman tradition, carried allegorical weight. The problems that characters like Esther Lyon, Fred Vincy, and above all Gwendolen Harleth encounter as they grow up are not arbitrary: they follow logically from each character’s egoistic selfishness, which is why they can only be overcome with moral awareness. But this isn’t something that Eliot ever says directly, never mind indicating how her thinking about egoism and metaethics connected to the extensive nineteenth-century debates on the topic. Hence my excitement when I read James Arnett’s excellent essay ‘Daniel Deronda, Professor of Spinoza,’ which contains this amazing footnote:

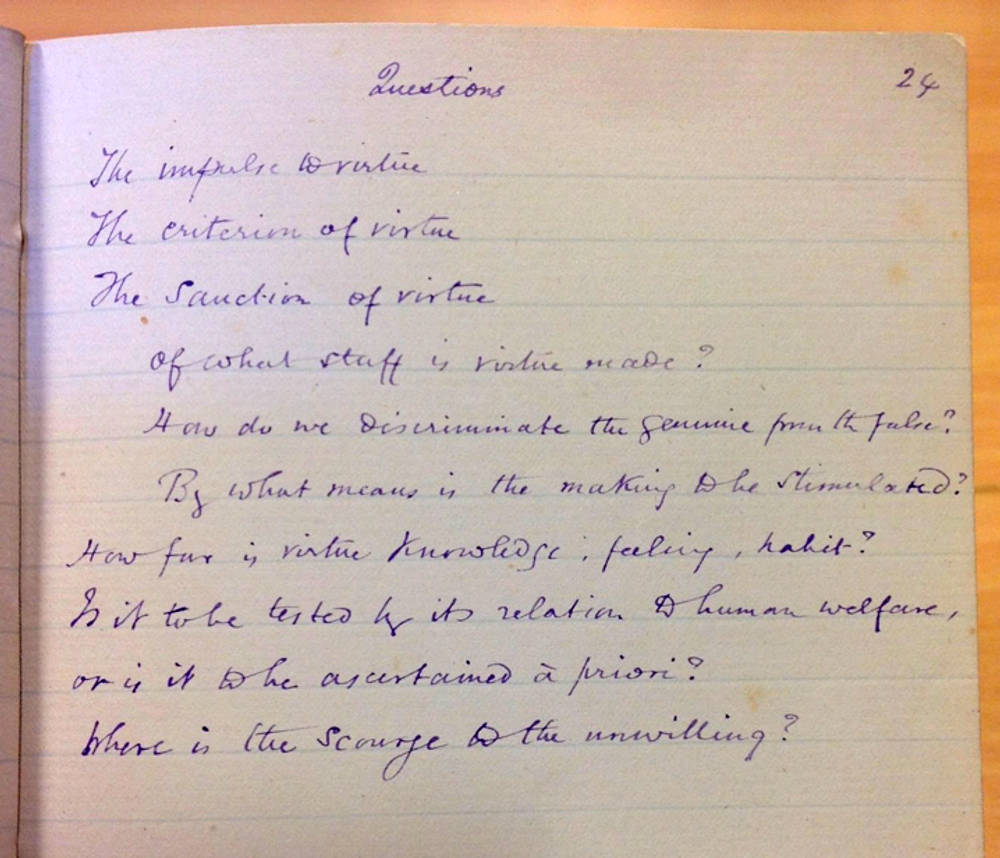

12. In a notebook housed in the Beinecke Rare Books and Manuscripts Library at Yale University, Eliot prefaces her notes and reading of Kant’s ethics with a series of questions that points to an earlier node in her philosophical development. Headed ‘Questions,’ in ‘Notebook kept while studying Kant’, they proceed:

Questions

The impulse to virtue.

The criterion of virtue.

The sanction of virtue. of what stuff is virtue made?

How do we discriminate the genuine from the false?

By what means is the making (to be) stimulated?

How far is virtue, knowledge & feeling [a] habit?

Is it to be tested by its relation to human welfare, or is it to ascertained a priori?

Where is the scourge of the unwilling?

[Click on images to enlarge them.]

Here was Eliot writing directly about exactly the problem I thought was so central to her work: the sources of virtue, and in particular the peculiar manner by which moral norms obligate those who don’t recognize them. Eliot's last, gripping question—‘Where is the scourge of the unwilling?’—distils the problem of egoism into a single memorable phrase. What possible ‘sanction,’ after all, could ever scourge someone too selfish to care about other people into eventually doing so? And—icing on the cake—it’s labelled ‘NOTEBOOK kept while studying Kant.’

Obviously, I needed to read this notebook for myself. But when I contacted the Beinecke to ask for a copy, it turned out I had stumbled into a mystery. The book Yale has is apparently a copy of a copy of Eliot's notebook: one Mrs. Joy Hooton—possibly the Australian writer?—apparently had her personal copy in New Haven in 1984, and someone made a copy for the Beinecke’s collection. But since Yale didn't have the original, they didn’t have the rights to share digital copies.

Unfortunately I didn't have any immediate plans or means to visit Yale, and anyway I really wanted to see the original. The Yale notebook is apparently labeled ‘original kept at Nuneaton,’ but I didn’t know what that meant. Where in Nuneaton? So I wrote to the Warwickshire library system, essentially saying ‘help!’ The magnificent staff there found two versions: a copy in a special Eliot collection at one of the branches, and the original itself at the Warwickshire County Record Office.

As it happened, I was planning a trip to Warwickshire anyway, for the great ‘Ethics, Tropes, Attunement’ conference Warwick University put together in April 2017. So I added a day to my trip and caught a bus to the Record Office. I’m not the kind of literary critic who spends a lot of time in archives, so it was wildly exciting to be working on a research question that brought me to one. And the notebook didn’t disappoint, although predictably it led me to more questions than answers.

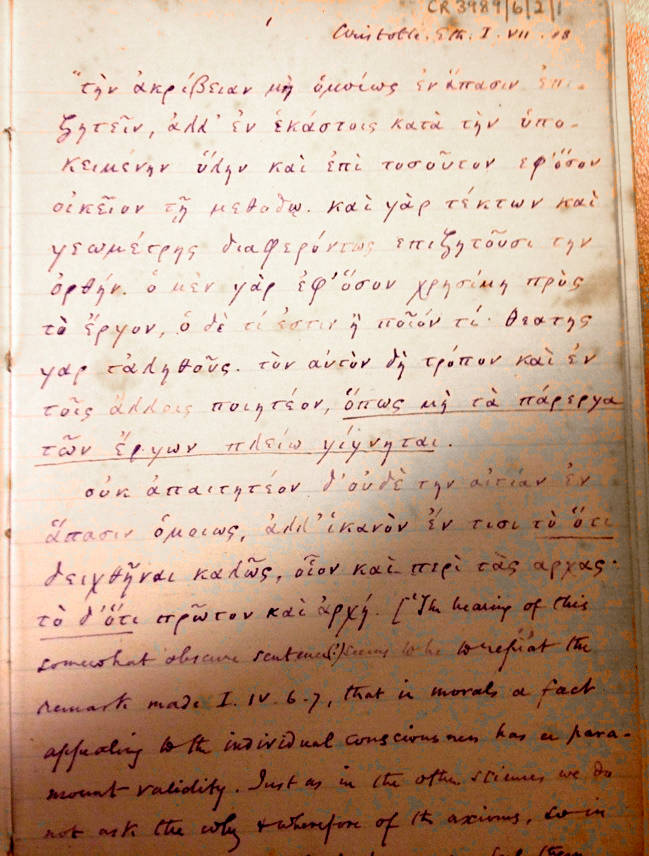

Eliot seems to have used the notebook mostly during 1876, while she was writing Daniel Deronda; there’s a note at the bottom of page 13 that says ‘re-read December 15 1876’ after transcribing a few passages from John Locke. And it seems to have been limited to philosophical purposes: she doesn’t jump to things like grocery lists or musings about whether Gwendolen should marry Daniel. But it isn’t in any way limited to her reading of Kant. Displaying the kind of education that just feels like showing off to 21st century readers like me, the first ten pages of the book are mostly transcriptions of and notes on her reading in Greek, ranging pretty widely across a variety of Greek philosophers but ultimately concentrating on Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics. Here's an example:

Book 7 of the Nicomachean Ethics is, incidentally, a very interesting thing for Eliot have to been writing about. It’s Aristotle’s famous discussion of akrasia or weakness of will, which is also a central and important problem in Eliot's moral thought, if not exactly the one I had come to Warwickshire to think about.

After that she changes periods, themes, and languages, copying out some passages in French from Descartes's Discourse on Method. Interspersed are little notes to herself, a passage from Leslie Stephen, an observation about the Hebrew roots of a word, a list of philosophers from Bacon to Comte with their lifespans (Spinoza died at 45, Newton made it to 85; Mandeville unfortunately wasn't prestigious enough to make the list, and just has his year of death—1747—noted in the margin).

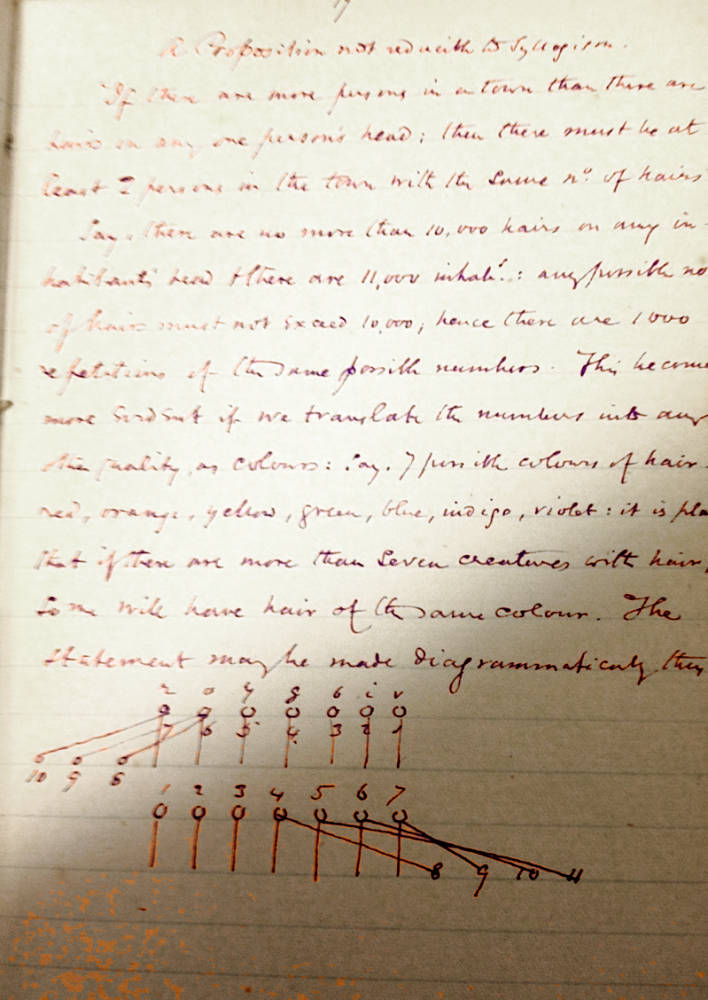

The most idiosyncratic page in the notebook is page 17, when she takes a brief pause to summarize a puzzle in mathematical logic. Here’s the page:

The puzzle (helpfully explained on Wikipedia!) is named the ‘pigeonholing’ problem. Imagine that you’re matching up the elements in two sets, and one set is bigger than the other. What that means is that at least one entity in the smaller set is going to get paired up with multiple entities in the bigger set. In the example of the chart Eliot draws for herself, suppose that we’re matching a group of ten people with the set of hair colors. Obviously, there are going to be some people in the group who have the same hair color, since there are (at least in Victorian England) less than ten colors of hair (Eliot lists seven): persons 4 and 8, on her chart, share a color. All this might sound pretty unsurprising, but it then yields the surprising conclusion Eliot starts with: if the population of a town is bigger than the number of hairs on a person’s head, then there will be at least two people in the town who have exactly the same number of hairs. Interesting as this was, I began to get the sense that this notebook was less likely to offer decisive insight into Eliot’s moral thought than to demonstrate that she occasionally got distracted and needed to work out some math problems on paper.

Her discussion of Kant begins on page 20. But she’s mostly interested in the Critique of Pure Reason, Kant's major work on epistemology and metaphysics (as opposed to the Critique of Practical Reason, one of Kant's major ethical works, and which I had come to Warwickshire suspecting to be a major influence on her own thought). And in 1876 anyway she doesn’t seem to have been reading Kant directly: several references to ‘Fischer’ suggests she was reading Kuno Fischer’s History of Modern Philosophy, probably volume 4 (Kant’s ‘System der Reinen Vernunf’).

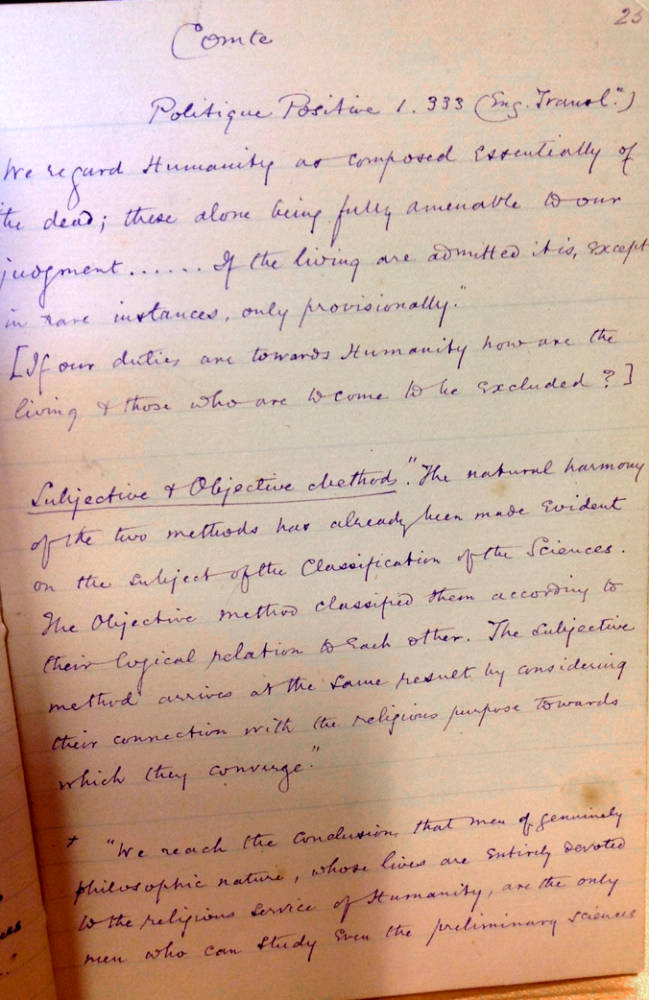

After the discussion of Fischer comes page 24, the ‘scourge of the unwilling’ page, which I had come to Warwickshire to see in its full context. But then, page 25 turns to a new thinker and a seemingly unrelated topic: August Comte and the relationship between subjective and objective methods in the sciences.

So, in one of those wonderful accidents of intellectual history, Eliot seems not to have been reading, or perhaps read and didn’t care about, the parts of Kant’s thought that addressed the question she was asking herself about the sources of normativity. Or perhaps she agreed so fundamentally with him that there was no need to say so to herself in a notebook. In any case, Eliot ultimately did arrive at an enormously sophisticated and creative account of the ‘scourge of the unwilling,’ one that reflects the enormous diversity of her reading and which plays a central role in the narrative arc of Daniel Deronda, and that I would be delighted for you to read about soon in my book The Ideas in Stories!

Created 31 October 2019