any activities, achievements and events were deprived of their fair share of attention when the Covid 19 pandemic became the focus of universal attention. Things that would normally have caught our eyes such as the latest publication, the announcement of a forthcoming exhibition or a recent appointment went way down everyone's 'need to know' list and then, of course, for a while there the stream of such news dried up anyway, when life as we were used to it was put on hold. This is by way of explanation for the belatedness of this review, of a meritorious, intelligent and valuable book that came out in 2019 but deserves the attention of anyone concerned with the art world of (roughly) 1880 to 1914.

This book derives from the author's doctoral thesis – a journey that is not always successful – but is eminently readable while being well informed and thoroughly documented. It belongs to a series called "Contextualising Art Markets" but is far more interesting and rich than that rubric might promise, examining topics such as art training, patronage, the selling of pictures, getting a reputation and earning a living, artists' associations and careers in the applied arts. These questions are considered with regard to cohorts or a generation (or two) of art-makers rather than to specific individuals, so readers will find familiar names such as Helen Allingham, Elizabeth Lady Butler, MEE (Mary Ellen Edwards), Kate Greenaway, Lucy Kemp-Welch and Louise Jopling mentioned repeatedly as illustrating an issue rather than profiled at concerted length. Many further names will probably be unknown to the non-specialist reader. Perhaps as a consequence of this approach, this book carries no illustrations – and the achievement of producing a satisfying book about art with no visual content shouldn't be under-estimated!

In her introduction, the author makes the general point that "middle-class women in the nineteenth century had access to art education but they were not generally expected to fully participate in the 'market economy'." (2) This premise leads her to return time and again throughout the book to the definitions of professional and amateur that determined and appraised women's work, and the various ways in which the female artist could therefore make a name, a living or an impact in late-Victorian and Edwardian Britain. She makes many apt and revealing comparisons between men's and women's prices and earnings, critical reception and patronage, and usefully situates artists as a population in a social palimpsest: for instance, a moderately successful artist in the 1880s and 1890s might be earning roughly the same as successful barristers, doctors and senior civil servants – although Millais and Leighton were bringing home at the same time at least ten times that per annum. (7)

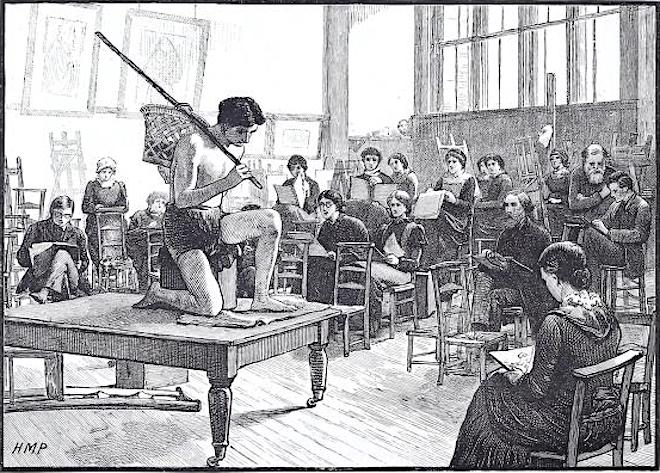

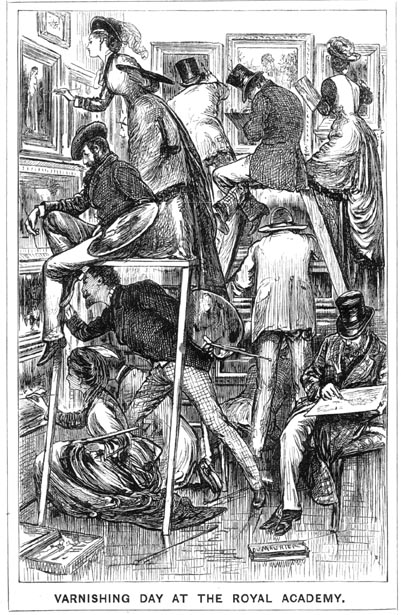

Left: Women attending a life class at the Slade. Right: Varnishing Day at the Royal Academy, by George Du Maurier (Punch, 19 June 1877), showing women among those exhibiting. [Click on the images for more information.]

The bulk of the book is divided into two sections, "From Student to Studio" and "Commerce, Enterprise, Display." Quirk proceeds to consider art training and how realistically it equipped women for a career: she is only too right in observing that "any perceived failures in women's art after they had received training could be positioned as proof that, even with a thorough education, women still lacked the 'natural' creativity and inventive power to create great art" (23). Next, the role of the family is brought into focus: a striking number of female artists managed to work professionally from home, but this tended to depend upon domestic autonomy or a supportive father/husband (in rare cases which Quirk doesn't remark upon, a mother or sister) such as Laura Knight and Harold, or Elizabeth Armstrong Forbes and Stanhope. The home that was also a studio was a mixed blessing with regard to the artist's image, as the professional teetered towards the amateur.

Naturally, the examination then turns to the single woman, where (rather ironically) the much-married Louise Jopling provides a lot of material; set against the case of Kate Greenaway, who is often overlooked for serious consideration despite her enormous public visibility in the period under discussion. This was also the age of the celebrity and the studio as a showroom, requiring a consideration of the identity of artist as a role to be performed for the public whose opinion and purchasing-power was so crucial to the artist's prosperity.

Although this period saw the relative decline of the Royal Academy's authority, Quirk is right to pay it attention, as the weight of its imprimatur persisted, indeed well into the twentieth century (look at how much is routinely made of Annie Swynnerton's and Laura Knight's elections to membership of this essentially passé body, in 1923 and 1927 respectively). The mismatch for women between exhibition at the RA, endorsement by it in the form of membership, and earning power, is very telling. Not surprisingly, then, as Quirk points out, when independent, artist-run and specialist associations "attempted to create new markets for art...[women] were interested in the new societies founded to represent their needs". (88) This development diversified the art-market but in too many cases did not progress at all with regard to sexual politics, nor seek to change hearts and minds in this respect. The case of siblings Augustus and Gwen John provide a compelling example here. More original examples brought to bear are the Hammond sisters, classic instances of reasonable success in their lifetimes that did not result in any posthumous reputation to speak of.

In scrutinising the ins and outs of making a living from art, Quirk devotes considerable attention to portraiture and, in turn, to what is often called (appositely) commercial art. The former, usually characterised after the Georgian era as the fall-back, pot-boiling genre, was not immune to the prevailing prejudices about gender, and it is not surprising that Quirk does not adduce any famous example of a female portraitist either in the twilight of the Victorian period or the first decade of the Edwardian – although there were several in the offing, who enjoyed recognition post-war. The detail of her final chapter, on the various forms of illustration in which women could participate gainfully, will be novel to many readers and thought-provoking for that reason. It is the kind of "art" that women's and girls' magazines were prone to recommending in the period, a business-like but sadly inglorious path to take.

This is a work of great utility, containing many sound ideas cogently conveyed, considerable fascinating detail, and a wealth of documentation and reference that will have the reader hurrying to their handiest library, actual or virtual. It's to be hoped that we shall see further publications from this author.

Links to Related Material

- Victorian Women and the Visual Arts (sitemap)

- Victorian Women — Social and Political Contexts (sitemap)

- Women at Work: The Slade Girls

- Discovering Women Sculptors, edited by Marjorie Trusted and Joanna Barnes (another review by Pamela Gerrish Nunn)

Bibliography

(Book under review) Quirk, Maria. Women, Art and Money in Late Victorian and Edwardian England. London: Bloomsbury, 2019. Paperback, £31.99. ISBN 978-1-3502-6368-0

Cooke, Simon. "'A genuine talent': Mary Ellen Edwards". in Nineteenth-century women illustrators and cartoonists edited by Jo Devereux. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2023. 93-112.

De Montfort, Patricia. Louise Jopling: a biographical and cultural study of the modern woman artist. London: Routledge, 2016.

">Worlds of Art: Painters in Victorian Society. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1990.

Haycock, David Boyd. Lucy Kemp-Welch 1869-1958. Woodbridge: ACC Art Books, 2023.

Helmreich, Anne. "The Marketing of Helen Allingham". In Gendering Landscape Art, edited by Steven Adams and Anna Greutzner Robins. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2000. 45-60.

Wynne, Catherine. Lady Butler, war artist and traveller, 1846-1933. Dublin: Four Courts Press, 2019.

Created 9 February 2024