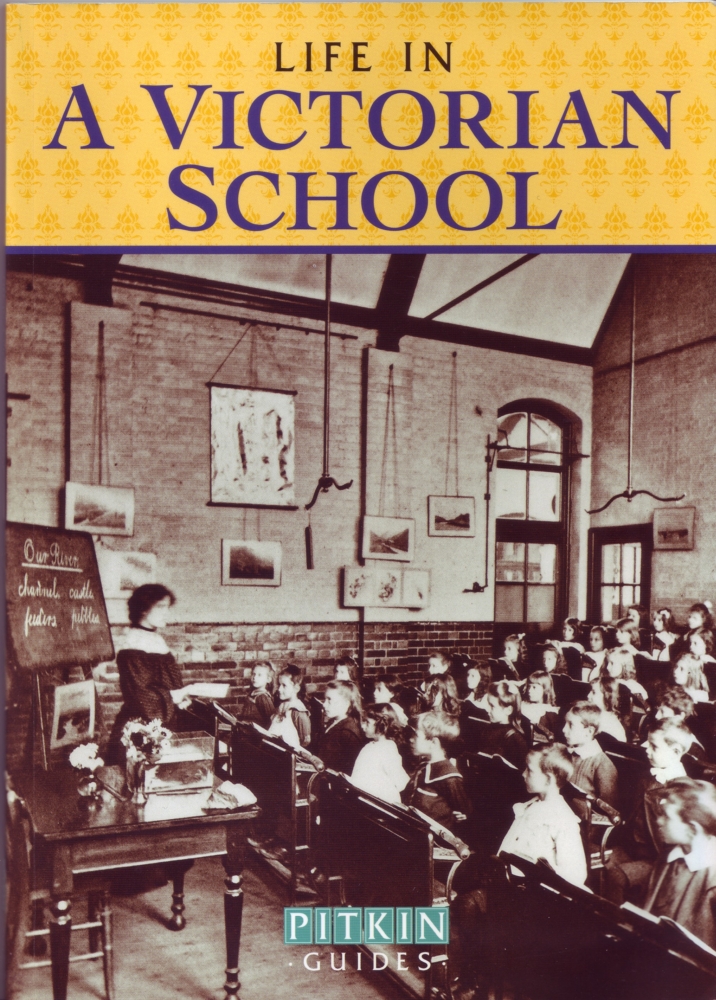

Cover of the book under review [Click on this and the following images, which are drawn from our own website, to enlarge them.]

Pamela Horn's Life in a Victorian School is only thirty-two pages long but it packs a wealth of information into a short space. Like other Pitkin Guides, it is attractively presented on glossy paper with the sort of format to be found on many websites. A typical page has a few paragraphs of text under one or two headings, accompanied by several fully captioned illustrations (historic photographs, charts, cartoons from contemporary magazines, and so forth), and some additional information in one or two coloured boxes.

As might be expected, Horn's emphasis is on reform and progress. She starts with a useful chronology, adding to the usual legislative milestones such important steps as the first time schools inspectors were appointed, in 1839, and the introduction of a teacher's certificate examination in 1846. She then covers a whole range of topics from "An Elementary Education" through to "Education's Evolution," which brings us briefly up to date with, for example, the controversial conversion of some state-funded schools to "academies." Her topics include the school day, school buildings, public schools, and girl's education. Facing the back cover is a list of "Places to Visit," mostly museums with displays on Victorian school life, and inside the back cover is a handy glossary with brief definitions of the different types and levels of education offered in the period, from Dame Schools and Ragged Schools to the several grades of secondary education available for the children from better-off families.

The school pictured (or caricatured) by Cruikshank here would have been a new establishment: Horn tells us that the Ragged School Union was formed in London in 1844. The idea was to give destitute children some basic education that would fit them for earning their own livings. "By 1852, 41 towns (including London) had Ragged Schools" (6). However, these disorderly scenes suggest that teaching the children was uphill work.

Far from being a dry collection of facts, Life in a Victorian School draws specific examples from schools all over the country, and gives a voice to everyone involved. In a coloured box in the "Different for Girls" section, for example, we hear the famous Miss Buss, pioneering principal of the North London Collegiate School, complaining to the Schools' Enquiry Commission in November 1865: "We have a large number of girls of 13, 14, or 15 who come to us who can scarcely do the simplest sums in arithmetic ... I think that such education as they get is almost entirely showy and superficial; a little music, a little singing, a little French, a little ornamental work, and nothing else..." (29). From the other side of the desk, we also have an account by one of the girls drawn into the elementary school system once compulsory attendance was established in 1880, showing that going to school could be almost as exacting as working in the fields or factories. "When we arrived at school, after starting as soon as ever it were daylight, in the winter, we were already exhausted and frez [sic] to the marrow," recalled Kate Mary Edwards, a pupil in the rural area of Huntingdonshire in the 1880s and 90s (11). Public school could make boys' lives a misery for different reasons, though Horn's emphasis, here as elsewhere, is very much on change for the better.

Left to right: (a) A former National School in Dent in the Yorkshire Dales, founded in 1845, looking rather bleak (b) The bell at Saltaire's Factory School in Yorkshire, opened in 1861. (c) A London School Board plaque on the façade of the architect E. R. Robson's Primrose Hill Infants School in north-west London, dating from about 1885. (d) An illustration dated 1896 by Edmund J. Sullivan for Tom Brown's Schooldays (at Rugby): "The Captain of the eleven scored twenty-five in beautiful style."

Despite the introductory nature of the guide, aimed at a general rather than a scholarly readership, even readers conversant with the area are likely to find something new and illuminating here. The 1870 Elementary Education Act, for instance, inspired the provision of schools for the disabled: within a few years the London School Board was offering classes for both the deaf and the blind. At the other end of the spectrum, public schools were not only promoting sports but introducing military drill. Rifle practice (with mock arms) was held even in preparatory schools. The Report of the Royal Commission on Public Schools in 1864 praised these fee-paying schools for producing young people able "to govern others and control themselves" and combine "freedom with order" (26). These were of course the future leaders not only of the country but also of the far-flung empire.

Among the more telling of the many illustrations in the book are a sheet of ten rules for pupils of the National Society's schools (No. 4: "The children must be sent to school clean and neat in person and dress," 7) and a chart showing the Revised Code of 1862 for the elementary school curriculum in state-aided schools (in Standard VI, a child should be able to read a "short ordinary paragraph in a newspaper or other modern narrative," 9). The National Society, founded in 1811, was a Church of England initiative, and its purposes were not simply educational. It was an important player in the educational scene: Horn points out that by 1860 "it owned about nine-tenths of all public elementary schools and enrolled about three-quarters of the pupils" (5). As for the Revised Code, this was the first attempt to standardise the curriculum and set the age-related goals that are the bug-bear of many teachers today, who would prefer a freer hand and think that their pupils' creativity is stifled by the uniformity it imposes.

This Pitkin Guide is highly readable and well-researched. It is ideal for its purpose, which is to present a whole range of interesting and specific factual information. It is not the place for raising issues, or adopting critical stances. All that is missing is a page of "Further Reading," to benefit those whose curiosity has been piqued rather than satisfied by it.

Related Material

- The Ragged School Museum

- Education in the Mining Districts (an article in the Illustrated London News, 1855)

- State Involvement in Public Education before the 1870 Education Act

- William Edward Forster, MP, and Universal Elementary Education

- Edward Robert Robson: Pioneering Architect of State Schools

- Public Schools

- The Public School Experience in Victorian Literature

References

Horn, Pamela. Life in a Victorian School. Pitkin Guides. Stroud, Gloucestershire: The History Press, 2013. 32pp. + inside cover material. £4.99. ISBN 978-1-84165-415-7.

Last modified 12 May 2013