Part II, pp. 31-65 of Crastre's book, translated into English by Frederic Taber Cooper, and formatted for the Victorian Web by Jacqueline Banerjee. Page numbers are given in square brackets. All the illustrations come from the same source. Click on them to enlarge them, and for Crastre's full captions.

His Best Years

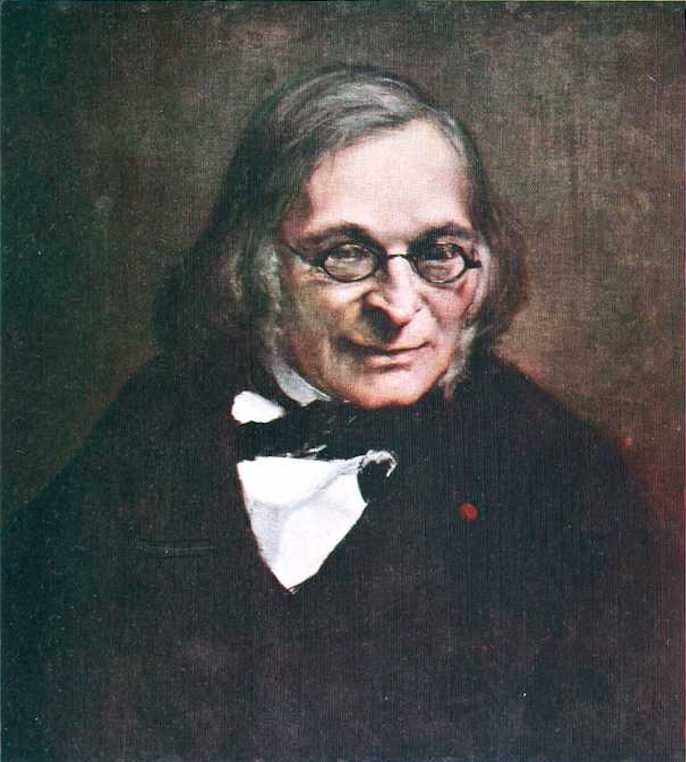

Plate II: M. Wallon (following p. 12).

The same year that he failed for the second time in the competition for the Prix de Rome, Bastien-Lepage painted The Portrait of M. Wallon, which is one of his most important works as a portrait painter. In spite of its tendency towards naturalism, this canvas was nevertheless still conceived in accordance with the established technique, and the keen and serious visage of the Father of the Constitution standing out against its sombre background is a fine study in chiaroscuro.

But the following year he struck the naturalistic note more strongly in his Portrait of Lady L., the only full-length, life-sized portrait that he ever painted; and he declared himself plainly and definitely a realist in his picture entitled My Parents. It would be impossible to find two figures more life-like, more literal, or painted with [31/32] greater sincerity. This canvas amounted to a declaration of principles; for an artist whom filial piety cannot turn aside from the truth will never make sacrifices to convention: he will never consent to embellish or idealize his models through tricks of his craft; he will paint them as he sees them, without correcting any of the imperfections and ugliness with which nature has afflicted them. How clearly we recognize that these likenesses of Bastien-Lepage's parents are absolutely true to life, and how much better we like them as they are, in the simple intimacy of daily life, than if they had been decked out, all spick and span, as a less scrupulous artist would inevitably have shown them to us!

Bastien-Lepage's brother, himself a painter of some talent, has preserved in his studio at Neuilly a certain number of the artist's works, which he surrounds with pious care and feelingly exhibits to occasional visitors. The family portraits are there, pulsating with life and radiating that gener[34/35]ous peasant kindliness which finds expression in a broad and tender smile. The father, seated in a chair in his garden, an old man with shrewd yet friendly eyes, seems so real, so actual, that we almost expect him to step down from his frame to bid us welcome. And what a marvel the Portrait of my Mother is, which forms a companion piece on the same wall! A somewhat wistful charm pervades this face, with its deeply graven lines, and an infinite tenderness, a true mother's tenderness, hovers over the thin, pale lips.

Perhaps this is the moment, in the presence of these pictures, to emphasize Bastien-Lepage's great value as a colourist. Few contemporary painters have used colour with so much tact, such veritable mastery as he. Others have employed more dazzling tonal schemes and have achieved more gorgeous effects, but no one has rendered with such exact truth the tints of the flesh, the grayish folds of wrinkles, the profound light of the eye. And his colour is always clear,[35/36] always unmistakably employed to produce a sought-after effect. There is no artifice, no trick-work, it is all straightforward, honest, precise; the opposition of light and shade never result in opacity, bitumen plays no part in his canvases, the astonishing relief of which is obtained by means of such perfect simplicity that it recalls the inimitable technique of Correggio.

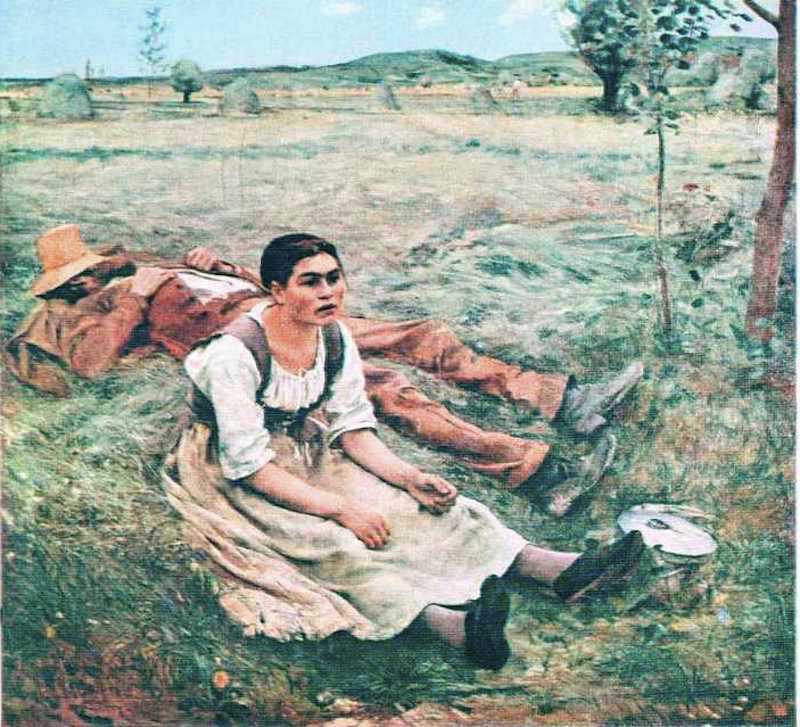

Plate IV: Hay-making (following p.32).

In 1878 he exhibited Hay-making, that magisterial page from the life of the fields which to-day is the pride of the Luxembourg museum, and which the art of the engraver has scattered broadcast to the extent of millions of copies.

This picture represents a vast sun-bathed meadow, overstrewn with new-mown hay and punctuated, here and there, by the rounded cones of the stacks. Against the blue background of the sky, green hill-tops trace an undulant line. In the foreground a robust, bony-armed country-woman is seated on the grass, her legs stretched out before her in an attitude expressive of the utter[Pg 37] weariness resulting from the work performed. Her head, solidly planted on her massive neck, is a marvel of realism; in her vulgar peasant face we may read health, strength, and a sort of dulled mentality born of physical fatigue. In every fibre of her exhausted body the woman is veritably resting, and through her half-parted lips it seems as though we could detect the passage of her hurried breathing. The man beside her, no less worn out than she, is stretched at full length on the thick couch of grass, and with his hat over his face, to shelter it from the sun, he is sleeping as though dead to the world.

Every detail of this canvas is perfect, because every detail is true, drawn straight from life, the fruit of minute observation. In it Bastien-Lepage once more affirms his predilection for the open country; and nothing could be more impressive than these two uncouth, vulgar, homely human beings, set amid the splendour of a meadow turned golden by the sun. It is an every-day spectacle; it [37/38] would not seem at first sight to contain material for a picture. But Bastien-Lepage has succeeded in proving indisputably that beauty does not consist solely in the harmony of the body, but in the impression which emanates from scenes that are most humble in outward appearance. In these few square feet of canvas the artist has summed up, perhaps without intending it, all the majesty of nature and all the grandeur of the life of the fields. It is scarcely necessary to add that this work is a transcript of the soil of Lorraine, that good natal soil which he loved so profoundly and to which he returned eagerly, year after year.

Bastien-Lepage was exclusively the painter of the rural aspects of Lorraine; he loved its horizons, its fertile and undulating plains. And when, occasionally, he ventured into allegory, the background was still Lorraine, and the characters were developed in the familiar setting of his native village, Damvillers. And how he loved it! How he enjoyed the warm atmosphere of affection [40/41] which always awaited him when his father, grandfather, and valiant and devoted "little mother" gathered at night around the family table! He made his home in Paris, because residence there was indispensable, both for business and artistic reasons; but the moment that he could escape from the capital and its constraints, he would go to rest and gather new energy in the midst of the family circle. He had a spacious studio installed in the second story of the ancestral home; and there he worked, absolutely happy so long as he could see the old grandfather at his side, pipe in mouth, examining the work with a knowing air, and the father and mother in a sort of ecstasy, as they watched him fill in his canvas.

Plate V: Portrait of Adolphe Franck (following p.38). [Note: this portrait is misidentfied in the text, as that of M. Hayem. — JB]

Nevertheless, Bastien-Lepage was no studio painter; it was not from the height of a window that he chose to contemplate nature, but in the open fields, in the very heart of the furrows; and it was there also, in the midst of the wheat and the rye, that he set up his easel and painted his [41/42] peasants in action, in the daily fulfilment of their thankless task. And by picturing them thus, without artifice, in all their simplicity of gesture and coarseness of feature, he imbued his canvases with a profound spirit of poetry, through which the often brutal realism of his subjects was redeemed and ennobled. In the presence of these peasants he experienced a joy more genuine than he had ever felt before the rarest canvases in any museum. Not that he denied or disdained the genius of the great ancestors of painting; he had too much reverence for his art ever to dream of doing so. But when it came to a question of training, he could learn more from nature than from them. Listen to his own exposition of his ideas:

"What a pity," he wrote, "that we are initiated, whether we will or not, into traditions and routines, under the pretext that this is the way to train us to be artists! It would be so simple to teach the use of brush and palette, without ever once mentioning the name of Michelangelo [42/43] or Raphael or Murillo or Domenichino! We could then go home, back to Brittany or Gascony, Lorraine or Normandy, and peacefully paint the portrait of our own province; and if some morning the book we had chanced to read aroused the wish to paint a Prodigal Son, or Priam at the feet of Achilles, we could reconstruct the scene to suit ourselves, without needing to resort to the museums, taking the setting from our own surroundings and making use of the models close at hand, as though the old drama dated only from yesterday. That is the way for an artist to succeed in breathing the breath of life into his art and in making it beautiful and appealing to the eyes of the whole world. And that is the goal towards which I am striving with all my strength."

As painter of the open air, he became in a certain sense the founder of a school, without meaning to be; for his conception of the painter's art won over a whole group of young artists who united in hailing him as their master. Each year [43/44] his offerings to the Salon were impatiently awaited, and his followers gathered in full force before them, discussing, comparing, acclaiming; each Salon became the occasion for a new success, the critics were unanimous in praising him, the public adopted his pictures for their own, because they could understand his clear and rigorous manner. Whatever hostility he met with was among his own colleagues, at least among such of them as were discouraged and humiliated by his vigorous originality. Nevertheless, the Exposition of 1878, at which he had gathered together all his works, was an especially triumphant occasion for him; yet when the awards were distributed, he discovered that he had received nothing but a medal of the third class.

At the Salon of 1879, Bastien-Lepage exhibited his Women gathering Potatoes, which formed a companion piece to his Hay-making. Here again we have the landscape of Lorraine and the eternal and infinitely varied theme of rural labour. In a sun-parched field two women are toiling to reap [44/ 45] the harvest of potatoes. While the one in the middle distance is stooping to turn up the ripe bulbs from the soil, the other, placed in the foreground, is striving to empty the contents of her basket into a sack which she holds open by a wonderfully natural movement of her knee. Nothing could be simpler or more humble than this subject, and yet one feels drawn towards it, conquered by the truth of these two figures, both in their attitude and their expression. Involuntarily memory conjures up another canvas, The Gleaners, and we realize that it is impossible to resist that higher appeal which the great artists succeed in giving to the most commonplace episode of farming life. But, unlike Millet, Bastien-Lepage does not awaken in us any compassion for these beings who toil, stooping above the earth; no touch of bitterness saddens his pictures, and the types which he shows to us have the healthy vigour of peasants who live their lives in the open air and love the soil which nourishes them.[45/46]

This picture, when it appeared, produced a sensation. Coming directly after the Hay-making, it definitely established Bastien-Lepage's talent and placed him in the foremost rank of painters of rural life. The critics hailed this powerful canvas with enthusiasm. Théodore de Banville, writing of the Salon of 1879, said: "M. Bastien-Lepage is the king of this Exposition. Young as he is, he has started in to produce masterpieces: he is very wise! For in later years an artist continues to copy himself, with more or less cleverness and success; but the creative genius has taken wing, like a bird on whose tail we have failed to drop the indispensable grain of salt. The October Season pictures the harvesting of potatoes. The earth, the encompassing air as far as we can see, the sky, the solitude laden with silence, are all evoked for us in this picture by the sincerity of its powerful painter; the peasant women are done in a masterly manner, and precisely for the reason that he has seen them apart from all convention[Pg 47] and has not tried to idealize them by any hackneyed device."

Albert Wolff was no less enthusiastic: "The colouring in Women harvesting Potatoes is ingratiating and discreet; not a discordant touch disturbs the beautiful harmony of this canvas, over which the silence of the open country has descended, enveloping the obscure toil. It is only artists of superior powers who can embody so much charm in a single conception."

Another feature of the same Salon was his magnificent portrait of Madame Sarah Bernhardt, a marvel of expression and of delicate art, embodied in a pale symphony of tenderest whites, blending harmoniously with the warmest tones of gold. The great tragic actress is portrayed draped, almost swathed, in a gown of white china silk, verging on the faintest yellowish caste; she is posed in profile, that cameo-like profile that has so often been portrayed. She is seated, with a sort of intentional rigidity, on a white fur robe, and is[Pg 48] examining a statuette of Orpheus, in old ivory, which she holds in her hands. Her expressive and intellectual features are treated with a vigour which does full justice to the classic beauty and virile energy of the sitter.

"The work as a whole," wrote the critic of the Revue des Beaux-Arts, "possesses supreme distinction and an admirable delicacy of colouring. The silvery tones of the whites, the warm grays of the draped gown lead up to the freshness of the delicate, rose-like flesh tints, beneath the crown of close curled locks that seem at once massive and weightless. The artist's hand was sure of itself; it neither groped nor hesitated. The execution is such that the drawing of the gown and the lines of the face seem to have been traced by an engraver's tool. In this case, however, definiteness has not resulted in stiffness. The sharp design has not imprisoned unwilling forms; it leaves them free to move as they please within the limits of their contours which are its domain. It is worth[50/51]while to examine with a lens the marvellous process which, by the aid of imperceptible half-tones, has softened the modelling of the face and hands."

Bastien-Lepage possessed the rare quality of being able to bestow the same superior skill upon every part of a portrait. Being sincere before all else, he never tried to shirk any difficulty; this is seen in the care he took in painting the hands of all his various sitters, showing something akin to vanity in the marvellous talent he displayed in rendering them. In this portrait — just as in all the others—the hands are quite as truly a miracle of execution as the face itself.

These two pictures earned Bastien-Lepage the Cross of the Legion of Honour and a definite recognition of his talent. The artist could not keep his delight to himself and, good son that he was, wished to share it with his beloved family; so he sent for them, to pay him a visit in Paris. The grandfather and the "good little mother" arrived, full of pride in this famous son, of whom the whole world was talking. He showed them the sights of the city and was only too happy to have a chance to introduce them to his friends; he took his mother to the big shops and insisted on choosing silk cloaks and silk dresses for her. The poor woman protested, saying that they were far too fine, that she would never dare to wear anything like that. "Show us some more," ordered the devoted artist, "I want mamma to have her choice of the best there is!" [52/52]

After the old people had returned home to Lorraine, Bastien-Lepage set out for England, where he was to paint the portrait of the Prince of Wales, who afterwards became King Edward VII.

In this portrait of tiny dimensions the Prince is represented in fancy costume, after the manner of Holbein. His garments recall in a measure those worn by King Henry VIII, in the celebrated portrait done by the great painter from Basle. The Collar of the Golden Fleece is displayed upon his breast. In the background of the picture may be seen dimly, through a veil of mist, the panorama of London and the gray ribbon of the Thames. The portrait is a little gem, which Bastien-Lepage wrought with the minuteness and affectedly hieratic mannerism of Holbein and the French primitive school. Although at present in possession of M. Émile Bastien-Lepage, it will eventually find its place, together with a goodly number of other canvases, in the museum of the Louvre, to which the brother of the great artist intends to bequeath them.[52/53]

It should be mentioned here, in connection with this work, that Bastien-Lepage continued to make more and more of a specialty of portraits of reduced dimensions, and that he acquired in this respect a reputation of the first order. He loved these little canvases, scarcely larger than miniatures, and he expended on their scanty surfaces an inimitable skill; he embellished them with a wealth of accessory detail which brings to mind, as we look at them to-day, the formidable labours of the illuminators of the middle ages. But this goldsmith's work, far from impairing the effect of the whole, adds a certain fascination to it. And he expended upon the study of the face the same degree of devotion that he gave to the rendering of a garment. His models relive with an intensity of life such as could be expressed only by an artist who has made a life-long study of nature in her minutest manifestations.

To name over his portraits would be to mention an equal number of masterpieces. The catalogue [53/54] would be too long, for Bastien-Lepage was an indefatigable workman. We may content ourselves with citing those that are most widely known: that of M. Andrieux, one-time Prefect of Police, whose refined features are rendered with striking truth; that of J. Bastien-Lepage, the artist's uncle, which is here reproduced and which shows him violin in hand, a clear and vigorous piece of brush-work, transcribing life in telling strokes, with an astonishing simplicity of means. This fine example is to be seen to-day in the museum at Verdun. And in the same museum there is still another that deserves mention; namely, the excellent Portrait of M. X. And we must not forget the Portrait of André Theuriet, born, like Bastien-Lepage, on the banks of the Meuse and attached to the painter by ties of almost fraternal affection. One feels that, in this picture, the heart must have guided the hand, for it would be difficult to find another work more magisterial in execution and more delicate in finish. And lastly, there is [54/55] Mme. Bastien-Lepage, the "good little mother," as the great artist and loving son used to call her. He posed her in the garden of the home at Damvillers. She is seated on a stone bench; on her knees rests a large garden hat; her two hands are crossed, one over the other, and in the left she holds a little bunch of field flowers. She is clad in a loose dress of sombre colour, cut with a pelerine; and nothing but the one bright spot formed by the white collar reveals the severity of the costume. The whole attitude of the body in repose is perfect in its truth and naturalness; but our admiration changes and quickens to emotion when we raise our eyes to the level of the face of this "good little mother," a bony, irregular face, almost ugly, but so gentle, so kind, so touchingly illumined by the tender caress in the eyes as they rest upon the adored son in the course of painting her. Those emaciated features, which not even the crown of blonde hair is able to rejuvenate, are unmistakably those of a mother; if we had not [55/56] known, we should inevitably have divined it; no one but a son, and a great artist as well, could have crowned the brow of a woman with such an aureole of gentleness and love.

Bastien-Lepage, whom those who envied him affected to regard as dedicated wholly to the reproduction of rustic uncouthness, had no equal in catching the radiance of feminine charms, even in their subtlest manifestations. No one was more skilled than he in seizing and recording the one particular trait, often elusive and intangible, which characterizes a woman and makes her beautiful. What delicious portraits of women we owe to him! Where could we meet with a more smiling image than that of Mme. Godillot, radiant and seductive, a rosy vision in the black velvet of her gown, relieved by the brilliant sheen of her white satin corsage! And what studied and elaborate art was expended on the Portrait of Mme. Klotz, whose magnificent brunette beauty emerges like a gorgeous lily from the surrounding whiteness of [56/57] her scarf, that is all the more dazzlingly white by contrast with her sombre robe! And still again, there is the Portrait of Mme. Juliette Drouet, another beautiful and noble specimen of portraiture. And how marvellously Bastien-Lepage could detect the hidden soul lurking in the inmost recesses of his models and reveal it behind the transparent screen of their eyes! If Bastien-Lepage had not achieved eternal glory as an interpreter of rural life, he would still have remained celebrated as a portrait painter.

But to Bastien-Lepage portrait painting was only a side issue, a form of relaxation between two landscapes; his predilection, his one object in life, so to speak, was to return constantly to his peasants, his scenes of toil, his fields of Lorraine.

After his return from England he passed some months at Damvillers, when an impulse seized him to visit Italy, to which the verdict of a prejudiced committee had once upon a time barred his way. He proceeded straight to Venice, and it[Pg 58] may as well be acknowledged at once, Venetian art left him cold, if not indifferent. He had never in the least understood any of the big "set pieces," and in spite of all the art of Veronese and Titian, in spite of their dazzling flare of colour, he never succeeded in understanding their sumptuous allegories or in accepting the fantastic interpretation of nature which the Venetians allowed themselves. He returned to Damvillers, profoundly disillusioned and more than ever convinced that nature alone, such as he saw it, was deserving of the attention of the true artist. There would be no object in discussing here how rightly or how ill founded such an opinion was; we note it only to indicate once more the absolute independence of the painter, his fixed determination never to imitate anyone.

And, beyond question, there is no resemblance to any other painter in that curious and remarkable picture known as Jeanne d'Arc listening to the Voices. Lorraine in heart and soul, Bastien-Lepage desired to pay his tribute, as so many had done [60/61] before him, to the glorious heroine who, like him, had come from the banks of the Meuse. And he wished also to restore her to her natural setting, with the greatest degree of historic accuracy. Consequently it is in a Lorraine garden surrounding a Lorraine cottage that he shows us Jeanne, the shepherdess; around her are the familiar garden utensils such as peasants use to-day just as they did in the fifteenth century. She is standing in an inspired and attentive attitude, which gives to her whole countenance that forceful character which Bastien-Lepage imprints upon all his compatriots. For he wished to make her, in a certain sense, a composite type of the women of the Lorraine race, such as Theuriet has described: "The forehead low but intelligent, the eyes with drooping lids that half conceal the somewhat sullen glance; the bones prominent in cheek and jaw, the chin square, indicative of an opinionated race; the mouth large, with half parted lips, through which one perceives the passage of the deep-drawn [61/62] breath." This head is always the same; under all the variations in physiognomy we always meet with the same local type: it is the head of the woman in Hay-making and of the Women gathering Potatoes, and it is also that of the "good little mother," so fundamentally and emphatically representative of Lorraine.

Plate VII: The Little Chimney-Sweep (following p.58).

Nevertheless Jeanne d'Arc listening to the Voices was rather badly received by the critics. Without disputing the originality and vigour of the inspired shepherdess, they reproached the artist for the presence of the traditional saints. Bastien-Lepage had indicated these under the form of luminous vapour, radiating through the branches overhanging the garden: St. Michael in the golden armour of a knight of the fifteenth century, St. Margaret and St. Catherine as phantoms so diaphanous as to be hardly perceptible. The idealists complained that the picture was lacking in idealism; the realists were somewhat disconcerted to find the apparitions there at all. It must be[Pg 63] acknowledged that Bastien-Lepage ceases to be himself the moment that he ventures to attempt the supernatural or even allegory pure and simple. He feels that he is no longer on familiar ground, he hesitates, he fumbles, and the harmony of the work suffers in consequence. Nevertheless, in spite of this undeniable defect, the face of Jeanne d'Arc will be remembered as a piece of powerful painting and genuine inspiration.

At all events, Bastien-Lepage was keenly aware of the half-way nature of his success, and from that day renounced forever the element of the marvellous and confined himself to that concrete and tangible poetry which emanates from the earth.

Some little time after his

In 1882 he won a further success with his superb Father Jacques, a masterly study of the Lorraine peasant, and with his charming Portrait of Mme. W.

In 1883 came Love in a Village, one of his most popular canvases, in which he depicted with charming naturalness the uncomplicated and naïve courtship of rustic lovers. Here are a pair who are untroubled by curious glances; the nearer houses of the village are quite close by. Bending slightly towards his sweetheart, the man is murmuring his avowals in her ear, in a voice that, we suspect, is by no means steady. Strapping fellow that he is, he evidently lacks the habit of making pretty speeches; we can see that from the embarrassed air with which he twists his fingers. His words, however, are plainly not lacking in eloquence, for the girl, type of buxom young womanhood that we have already learned to know, has bent her head and, although her back is turned, we are sure that she is blushing as she listens to his declaration. A special atmosphere emanates from this picture, as well as that profound spirit of poetry which is inseparable from the eternal song of love.

Related Material

Bibliography

Crastre, François. Jules Bastien-Lepage (1848-1884). Frederick A. Stokes, 1914. Internet Archive. Contributed by University of California Libraries. Web. 12 March 2020.

Created 12 March 2020