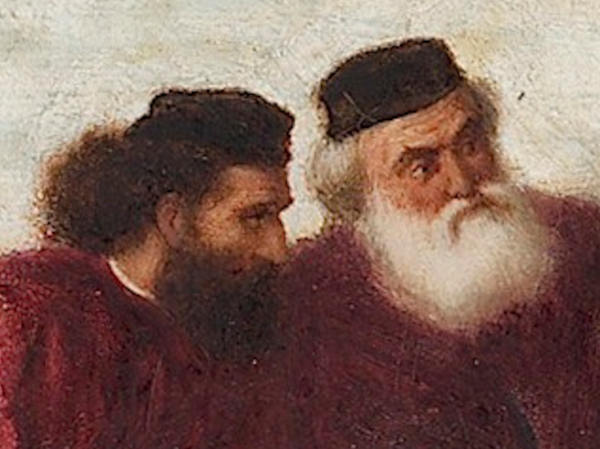

Found at Naxos, 1874. Oil on canvas, 12 x 19 inches (31.0 x 47.0 cm). Private collection. Click on image to enlarge it,

This painting was shown at the Royal Academy in 1874, no. 572. In his review of the exhibition Wallis's friend, the critic W. Cosmo Monkhouse, described the work as follows: “Two rich old Venetians, gorgeous in crimson robes, are seated on a marble bench, scanning, with critical eyes, an antique bronze which has come from Naxos, and is being held up for their inspection, by a dark-haired, black-skinned youth, who is expatiating on its exquisite qualities. If that youth were a true critic, and had this picture to sell, his face might properly wear some expression not much less ecstatic, as he pointed out its many claims on our admiration as a pure work of art” (29).

F. G. Stephens also praised this work in The Athenaeum for its subject and execution:

One of the by no means numerous designs which are marked by spontaneity of conception, and by their fine execution justify their existence, is Mr. Wallis’s From Naxos (572), showing the marble wall of St. Mark’s, at Venice, with the bench at its foot, and the two elderly merchants, in red robes and black caps, whom we saw last year seated in the same place, and in the receipt of ‘News from Trebizond’; but in the interval between the two pictures more than a year has passed over the head of the worthies. Their hair has whitened, and, although still hale, their forms are less erect than before. They still wear red robes, but of a crimson tint, which does not become them quite so well as the red proper. Nevertheless, they remain fine old fellows, and a new phase of life has come on them. A man does not stand cap in hand, but kneels before them this time; for there is no need to return with a message to the old merchants’ correspondents at Trebizond; all that is now over: the great carrack has, it may be, gone to pieces, or made their fortunes by its happy return. It seems more likely that the latter is the case, for what this kneeling man offers is a rarity of considerable price, and, apparently, not before known to the signors, being nothing les than Cupid, an antique relic, dug up, as it seems, in the Isle of Naxos, where our friends had dealings of yore, but for raisins and such like goods. They look at the relic with great interest and some hesitation. Here is Cupid at last, fresh as ever, though made in lustrous, dark, gold-hued bronze, and just rescued from the basket of that jovial Levantine sailor, himself a model of his kind, and one of the best designed figures Mr. Wallis has produced. We enjoy heartily the brilliant lighting, the rich colour, the rare spirit of this picture; but it suffers from tints, both of the gowns and the marble wall being a little forced, as if the artist had used gas-light too freely while he painted them, or, in an obedience to an afterthought, changed the gowns from red proper to crimson.” Stephens was later forced to retract part of his comments on this work in another review in The Athenaeum: “We come next to Mr. Wallis’s picture. We have already described it but we owe him an apology for our error in our account of it. The figure in the hands of the Levantine is not a Cupid, now presented to the merchants, but a nymph, whirling with a thyrsus” [740].

Click on images to enlarge them.

In 1878 a steel engraving of this subject was made by Peter Lightfoot for The Art Journal, whose commentary on the print stated:

“This picture was exhibited at the London Royal Academy in 1874. Why Mr. Wallis intimated that the little bronze figure which gives the work its title was "found at Naxos" we do not quite see. There were three places of this name known to the ancients, but neither of them appears to have been celebrated for artistic productions. The most famous of the three was an island, one of the large Cyclades in the Ægean Sea, about half-way between the coast of Greece and Asia Minor. It was taken by the Athenians in the time of Pisistratus, about five hundred years before the Christian era, and subsequently fell under the dominion of the Venetians, who built the castle of Naxia, the chief town of the island, and made it the residence of their dukes. The principal deity of Naxos was Bacchus, in whose honour a temple was erected there, it being, as stated by some ancient writers, the place where he was educated, and held in much honour. The artist has associated his picture with Venetian history. A sailor of that country presents a small bronze, which is assumed to have been "found at Naxos"— the title Mr. Wallis gave to the composition—to the Venetian noblemen, who are examining the "antique" with wonder and admiration. Whomever the figure may represent, it is clearly not Bacchus, nor can we definitely identify it with any one of the numerous personages in the long catalogue of classic deities. As was said of the picture when it hung on the walls of the Academy, ‘Mr. Wallis has not striven to present a picture of deeply significant meaning: he has only embodied certain types of national character in a graceful composition. There is just enough in the idea to create a certain fascination, imitative in some sort of that exercised over the two men attracted by the beauty of the small bronze. The composition is true and unforced. In the attitudes of the two figures there is no exaggeration, and the scheme of colour is a delicate harmony of warm tints carefully distributed over the space of the picture.’ It is a picture of simple yet inviting composition. [282]

A recent rediscovery was made of an oil sketch for A Despatch from Trebizond, the companion piece to Found at Naxos, which was almost exactly the same size as the known version of this subject. Both paintings were originally owned by the publishers Virtue & Co., who used them as the basis for the prints that appeared in The Art Journal. This strongly suggests that a large version of Found at Naxos also exists which has yet to be redicovered. The major version of A Despatch from Trebizond once belonged to Robert Kirkman Hodgson and was included in his estate sale at Christie’s in London on November 21, 1924 where it was listed as Announcement of War. A companion piece to this also sold at Hodgson’s sale, listed as Announcement of Peace. Despite the confusing title this may well have been the principal version of Found at Naxos.

Links to Related Material

Bibliography

“Our Steel Engravings: Found at Naxos.” The Art Journal, New Series XVIII, (1878): 282.

Lessens, Ronald and Dennis T. Lanigan. Henry Wallis. From Pre-Raphaelite Painter to Collector/Connoisseur. Woodbridge: ACC Art Books, 2019, cat. 97, 131.

Monkhouse, William Cosmo. At the Royal Academy. A companion to the oil pictures in the exhibition of 1874, London: Virtue, Spalding and Deldy, 1874.

Stephens, Frederic George. “The Royal Academy.” The Athenaeum, No. 2428, (May 9, 1874): 637-38

Stephens, Frederic George, “The Royal Academy.” The Athenaeum, No. 2431, May 30, 1874, 738-40.

Last modified 15 October 2022