[This article originally appeared in The Art Bulletin, 65 (1983), 471-84.]

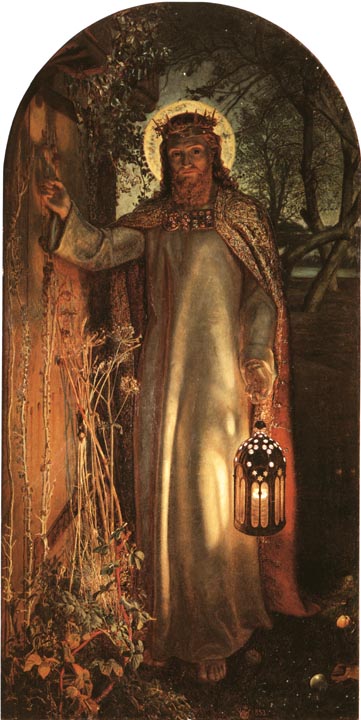

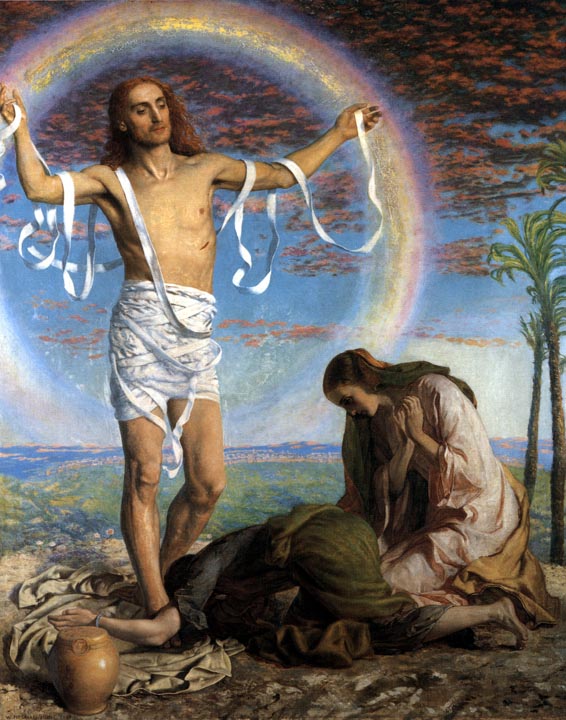

Left: The Light of the World. William Holman Hunt. 1851-53.>Oil on canvas over panel. arched top, 49 ⅜ x 23 ½ inches. Keble College, Oxford. Right: Christ and the Two Marys. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

lthough The Light of the World is unique because it records the experience of the artist's own religious conversion, it is but one of a large number of works he devoted to the general theme of sudden illumination. Like Tennyson, who developed a poetic form capable of conveying the experience of illumination long before the experience recorded in In Memoriam, Hunt was drawn to paint such subjects long before this vision of Christ came to him in the early 1850's. These earlier choices of this subject should not surprise us, since, as he told his friend, the painterpoet William Bell Scott, he always yearned for the wonderful and strange. Indeed, Hunt claimed that it was this yearning, which he took to be divinely implanted, that in the last analysis led him back to God. An early picture such as Love at First Sight (1846, Tate Gallery) thus reveals his habitual fascination with moments that are turning points in human life, though here, of course, the subject is secular rather than religious. In 1847 the young artist had in fact begun a subject of religious illumination with Christ and the Two Marys, but as he later explained in his autobiography, he abandoned the subject when he realized, "I could not justify [it] as according with my sincerest convictions," for painting something in which he did not believe would do nothing, he felt, "to make art a handmaid in the cause of justice and truth" (1, 72).

Rienzi vowing to obtain justice for the death of his young brother, slain in a skirmish between the Colonna and the Orsini factions. William Holman Hunt. 848-49. Oil on canvas, 34 x 38 in. Collection Mrs. E. M. Clarke.

Rienzi (1849), a subject of political conversion, provided Hunt with the opportunity to paint something in which he did sincerely believe. As the painter explained, his picture was inspired by the revolutions of 1848: ''Like most young men, I was stirred by the spirit of freedom of the passing revolutionary time. The appeal to Heaven against the tyranny exercised over the poor and helpless seemed well fitted for pictorial treatment. 'How long, O Lord!' many bleeding souls were crying at that time" (I, 114). Despite its relevance to contemporary events, Hunt's painting does not illustrate recent happenings but instead draws upon Edward Bulwer-Lytton's popular historical novel, Rienzi, the Last of the Tribunes, which first saw publication in 1835. As the novelist himself pointed out in a preface written for a reprinting in 1848, his tale of fourteenth-century Italy is "illustrative of the exertions of a Roman, in advance of his time, for the political freedom of his country" [ALS April 21, 1887 to William Bell Scott (Princeton University MS; Troxell Collection].Hunt chose to paint the moment at which Rienzi, the young scholar, became converted to political action. The painting's full title is Rienzi vowing to obtain justice for the death of his young brother, slain in a skirmish between the Colonna and the Orsini factions, and when he exhibited it at the Royal Academy he included the following passage from Bulwer-Lytton's novel to enforce his point:

But for that event, the future liberator of Rome might have been but a dreamer, a scholar, a poet — the peaceful rival of Petrarch — a man of thoughts, not deeds. But from that time, all his faculties, energies, fancies, genius became concentrated in a single point; and patriotism, before a vision, leaped into the life and vigour of a passion. (Book I, chap. 1, 23)

Even though this political messiah of the people ultimately met with defeat, such failure, the novelist insisted, was not his fault: the student of history will discover that "the vulgar moral of ambition, blasted by its own excesses, is not the true moral of the Roman's life: he will find that, both in his abdication as Tribune, and his death as Senator, Rienzi fell from the vices of the People" (Appendix I; p. 431). Cola di Rienzi was thus a savior of the nation who sacrificed his life for an unworthy people — a secular imitatio cristi. The novelist also points out that Rienzi can be considered a proto-Protestant political savior, for in him "a strong religious feeling was blended with the political enthusiasm of the people, the religious feeling of a premature and crude reformation" (Book II, chap. 6, 130n). For anyone considering the painter's choice of subject in one of his first Pre-Raphaelite works, it is particularly interesting to observe that he settled upon one that serves as an elaborate secular analogue to those he painted after his own conversion to Christianity.

Left: Valentine and Sylvia. 1851. Birmingham Art Gallery/Birmingham Museums Trust. Oil on canvas, 98.5 x 133.3 cm. 1887P953. Purchased from Christie's, 1887.. Right: Claudio and Isabella. 1850-53. Oil on panel, 29 ¾ x 16 ⅞ inches. ©Tate Britain, London. [

Hunt's two early Shakespearean pictures depict moments of dramatic encounter that also have elements of illumination. Whereas Valentine Rescuing Sylvia from Proteus (1851, Birmingham) portrays the climactic recognition scene from The Two Gentlemen of Verona, Claudio and Isabella (1853, Tate Gallery), which Hunt began in 1850, illustrates the prison scene in the third act of Measure for Measure when brother and sister reveal their true natures to each other. Claudio, who has been pleading with his sister to sacrifice honor and virtue to save his life, suddenly recognizes the horror of death while his sister perceives how corrupted and corrupting he has become.

These paintings, like Rienzi, reveal Hunt's fascination with such dramatic moments of illumination, but the painter did not turn to specifically religious versions of this theme until after his own conversion. The Light of the World, of course, depicts not so much a conversion taking place as the content of that vision Hunt claimed to have been his conversion experience. Moral and religious conversion, in contrast, is the explicit theme of The Awakening Conscience (1854), which he explained in Pre-Raphaelitism and the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood was "a material representation of the idea in 'The Light of the World.'" His intention, he further explained, "was to show how the still small voice speaks to a human soul in the turmoil of life" (I, 347). In other words, these two pictures, whose relation the painter seems to have conceived as analogous to that of the panels in those triptychs he had seen during his 1849 trip to the Continent with Rossetti, together furnish an image of the ways Christ and his grace affect human life. As Hunt also pointed out in a letter written many years after he completed the picture, "One intention . .. was to treat a literal fact of a kind that would illustrate the working of God's appeal to Sinners which in a spiritual manner I was illustrating in 'The Light of the World.'" Whereas his painting of Christ coming to the closed human heart provides a visionary image of God's part in salvation, The Awakening Conscience offers a specific example of this continually recurring event. Hunt therefore has created two images of the same "happening," each of which allows the spectator to perceive that event from a different perspective — the first from the vantage point of eternity and the second from a specific historical moment. This use of a visual realism to create an art that represents the way the eternal, the divine, enters human history recalls the work of the Early Netherlandish painters, and one assumes that Hunt drew upon their works for his notion of a multipaneled work. As a radical Protestant, Hunt did not depict a sacrament, such as the eternally recurring mass that some art historians find depicted in the works of Van Eyck or Van der Goes, but chose instead to portray a peculiarly Protestant theme — the Savior's visit to the individual sinner which produces conversion and a higher vision. (See, for example, Lotte Brand Philip, The Ghent altarpiece, 1971).

The Finding of the Saviour in the Temple. William Holman Hunt. 1854-60. Oil on canvas, 33 ¾ x 55 ½ inches .

From this point of view, The Finding of the Saviour in the Temple (1854-60) appears as one of the most significant paintings of Hunt's career. As his friend F. T. Palgrave indicated in a review for which the artist thanked him, this picture depicts the moment of Christ's own illumination or "conversion." ["The 'Finding of Christ in the Temple,' by Mr. Holman Hunt,'' Fraser's Magazine, LXI, 1860, 643-45. The quotations in paragraphs following appear on p. 644 of the original text. The artist thanked Palgrave for his review in a letter of April 20, 1860 (Huntington Library MS).] According to Palgrave, Christ's discourse in the Temple is "the single moment between the birth and the baptism noticed in sacred narrative ... [and] stands, we might truly say, as the turning-point from prophecy to fulfillment; the child's first consciousness of who he is, the earliest call to his mission, the revelation of himself to himself." Like Rienzi, a work painted before Hunt's own conversion, this picture illustrates the moment at which a savior becomes converted to his own mission. Palgrave insists both that the subject itself and the painter's treatment of it are Evangelical. Just as the great artists of an earlier day derived their theme and methods from Catholicism, so Hunt, a man of his age and faith, has derived his from the religion of his England — from Evangelical Protestantism:

It is the age in which he lives that has placed the artist at the point of view for a genuine evangelical treatment of scripture. Rendering all the other circumstances of the scene with an accuracy rarely reached in art and rarely aimed at, what he has mainly brought before us is the crisis in Our Saviour's earthly career, the first sense of superhuman nature and illumination, the ecstasy (to take a noble phrase from Sir Thomas Browne) of "ingression into the Divine Shadow."

In other words, the Evangelical tone of the painting appears not only because this faith that so emphasizes the centrality of individual conversion here leads the artist to portray the illumination of Jesus — the central one in all human history — but also because Hunt's manner, like that of the Evangelical preacher, helps the audience experience this event for themselves. According to Palgrave as according to Hunt, the realistic detail that so many critics took to be the incarnation of a purely scientific attitude functions to aid the spectator in experiencing the scene emotionally. The Finding of the Saviour in the Temple thus stands as William Holman Hunt's sermon on the illumination of Christ. The Shadow of Death, his next major religious work and the source of The Beloved, presents the illumination of Mary. The mother of Jesus has just gone once more to look at the gifts presented by the Magi, some of which suggested that her son would have earthly power and glory. She looks up to observe her son's shadow upon the wall and from it gains a prevision of his fate. Similarly, The Triumph of the Innocents also returns to the subject of spiritual illumination, for here both the infant Jesus and his mother receive consoling visions of the eternal. Hunt's conflation of the Flight into Egypt and the Massacre of the Innocents presents an image of the first martyrs to Christ. Mary and her son, both of whom can apparently perceive the other world of the spirit, find themselves surrounded by an entourage of guiding spirits who are awakening to their new, higher existence.

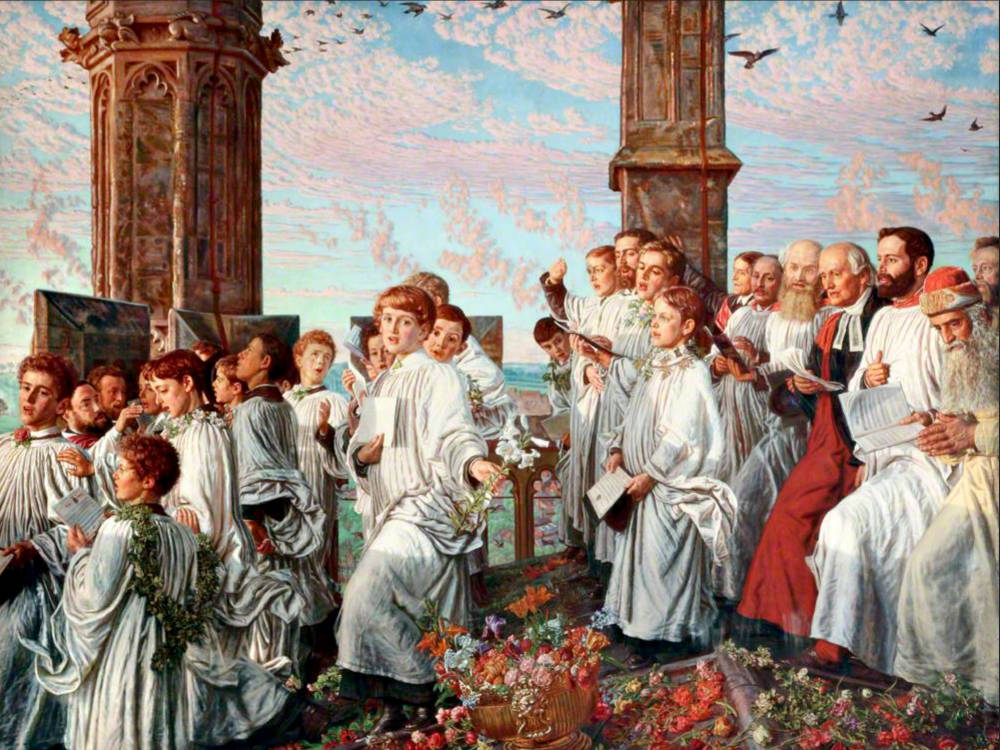

May Morning on Magdalen Tower. 1888-91. Oil on canvas 62 x 80 ½ inches. Lady Lever Art Gallery, Port Sunlight.

May Morning on Magdalen Tower (1890, Lady Lever Art Gallery) takes a different approach to combining the real and the visionary, for in depicting the traditional ceremony in which Oxford choristers greet the rising sun on the first of May — a literal illumination — this picture includes a Parsee, a Persian sun-worshipper, among the clergy and choir boys whose portraits Hunt so conscientiously recorded. The Miracle of the Holy Fire, which again presents an image of a ceremony in which men seek a divine gift of light and illumination, is essentially a failed encounter, a satiric image of what occurs when men attempt to rely upon conventions, dead forms, to capture life and spirit.

The Lady of Shalott. c. 1886-1905. Oil on canvas, 74 x 57 ½ inches. Ella Gallup Sumner and Mary Catlin Sumner Collection/ Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford, Connecticut

Turning to Hunt's last painting, The Lady of Shalott (ca. 1886-1905; 4), one may observe that although the picture does not concern itself primarily with religion but with the fate of the artist, it too presents a conversion, turning point, and illumination The Lady, apparently Hunt's image of the artistic and poetic imagination, finds her magical world in ruins after she has physically turned away from the truths of God and art, momentarily yearning for earthly love. As Hunt himself explained in the pamphlet he wrote for the painting's exhibition in 1905,

The parable, as interpreted in this painting, illustrates the failure of the human Soul towards its accepted responsibility. The Lady typifying the Soul is bound to represent faithfully the workings of the high purpose of King Arthur's rule. She is to weave her record, not as one who mixing with the world, is tempted by egotistic weakness, but as being "sitting alone"; in her isolation she is charged to see life with a mind supreme and elevated in judgment. In executing her design on the tapestry she records not the external incidents of common lives, but the present condition of King Arthur's court, with its opposing tendencies of good and evil. [Quoted in Mary Bennett's William Holman Hunt, , London, 57.]

Hunt's elaborate description, which leaves little doubt that he is setting forth his credo as an artist, concludes by explaining that the Lady, who has become weary of her isolation, wavers in her high purpose, becomes envious of the lives of common men, and "casts aside duty to her spiritual self.... Having forfeited the blessing due to unswerving loyalty, destruction and confusion overtake her ... her artistic life has come to an end" (Bennett, Hunt, 58). Hunt, who completed the small version of The Lady of Shalott before setting out in the autumn of 1892 for Jerusalem where he began The Miracle of the Holy Fire, alternated between work on the large version and his picture of the Easter Eve rite and seems to have seen them in some ways as contrasted pictures. Both pictures, it is true, represent failed or false illuminations — the one a realistic image of what occurs when men smother the divine light within them with superstitious ritual and unchristian violence, the other a mystical image, a parable, of how the artistic imagination is destroyed and loses its true "illumination," which must come from devotion to morality and religion.

Hunt's painting, which derived from his 1857 illustration of "The Lady of Shalott" in the Moxon Tennyson, obviously goes far beyond the original poem — though not necessarily beyond the poet's own ideas elsewhere in his work. In fact, Hunt's elaborate description of how the Lady of Shalott came to abandon her high powers owes a great deal to Tennyson's "Merlin and Vivien," one of the Idylls of the King which examines the rot and lack of confidence of late Victorianism under mythic guise. As literary critics have increasingly begun to perceive, Tennyson's Idylls of the King presents his contemporaries with a complex poetic analysis of what happens to a society that is having grave difficulties in having faith and keeping faith. In his last completed painting, Hunt, who had originally annoyed the poet by embroidering upon the poem in his earlier illustration, makes a very Tennysonian statement about the nature, dilemma, and fate of the late Victorian artist completely in keeping with the poet's own ideas.

Perhaps more important, the artist had also summed up his own artistic credo and the themes of his own late religious paintings, all of which in some way concern conversion, illumination, and the encounter of man and God. Hunt, who began his career wanting to ground all symbolic art in visual realism, increasingly became more willing to accept purely visionary painting. This new emphasis appears in his interest in painting parables, biblical and Tennysonian alike, and in his concern with illustrating conceits of popular hymnody. Nonetheless, this painter whose career contains an almost bizarre mixture of unity amid diversity did comment in his last religious paintings upon the way man tries, and often fails, to encounter his God.

Shadows Cast by the Light of the World: William Holman Hunt's Religious Paintings, 1893-1905

- Introduction

- Christ the Pilot

- The Importunate Neighbour

- The Miracle of the Holy Fire in the Church of the Sepulchre at Jerusalem

- The Beloved

Last modified 22 June 2007