We hold him for another Herakles,

Battling with custom, prejudice, disease

As once the son of Zeus with Death and Hell

[W. E. Henley, "The Chief," In Hospital]

Joseph Lister is unique in having memorial plaques at each of the University of London's founding colleges: he was a student at University College from 1843 to 1853, and a Professor of Surgery at King's from 1877-1892. He continued at King's College Hospital for another year after that, mainly in a consultant capacity.

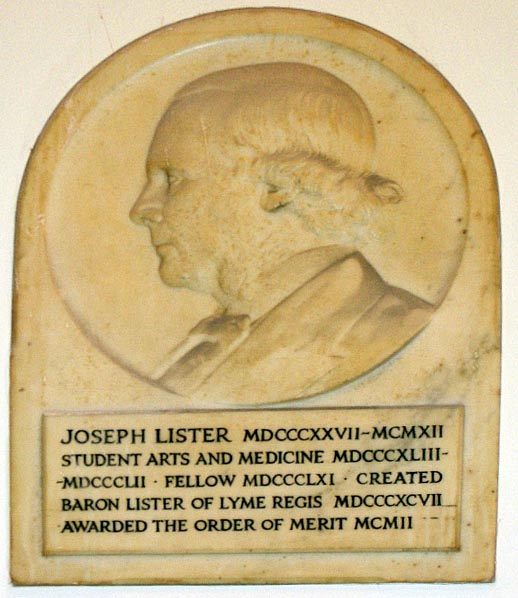

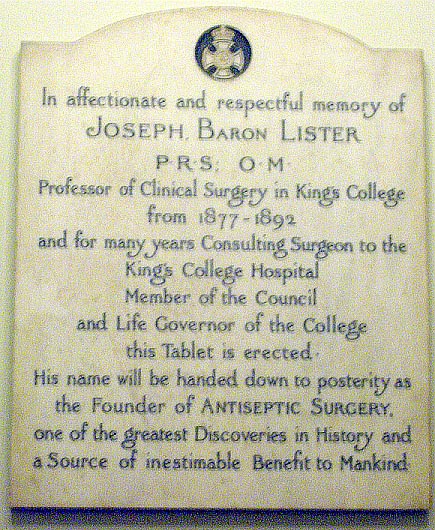

Memorial plaques for Lister at University College, London (left), and King's College, London (right). Click on thumbnails for larger images.

Born at Upton House in West Ham (then in Essex, but now very much a part of London), Lister was the fourth of seven children of a "scientifically minded Quaker" (Ellis 347). He was exactly the kind of student to benefit from the more practical education on offer at the non-sectarian University College. From boyhood, his main interest had been in natural history, and he first entered the college in 1843 to study a junior class in botany. He went on to read classics, mathematics and natural philosophy for his degree; but he already had his eye on his future, for he was present in 1846 when the first major operation in Europe took place under anaesthetic just across the road, in University College Hospital. On this celebrated occasion, the Scottish surgeon Robert Liston, known for his strength and speed in surgery, used "the Yankee dodge" of administering ether when amputating a patient's leg. The biographer Rhoda Truax reports that the young Lister "felt a tremendous relief surge over him as he realized that patients need no longer suffer the tortures of an operation" (29). Truax's biography is full of suspect "reconstructions"; still, it is clear that Lister was indeed a sensitive young man. After he received his BA in 1847, he went through a period of illness and nervous debility, provoked perhaps by his elder brother's harrowing death from a brain tumour. He seems to have suffered some kind of religious crisis as well. Only in 1849 did he settle down again at University College to pursue his medical studies.

In those days, the medical school at University College was still small, but it had the great advantage, especially for someone like Lister, of close links with experimental science in the college itself. The practical chemistry course for which he registered was particularly useful, since it "dealt extensively with the fermentation process and the role that yeast played in it" (Fisher 48). Also important for his future development was his work under William Sharpey (1802-1880), the first Professor of Anatomy and Physiology at University College, generally considered the father of modern physiology. Lister's father, himself an expert microscopist, had encouraged him to use a microscope from boyhood, and he responded wholeheartedly to this professor's insistence on close observation. As a result, while he did brilliantly in all his courses, he did especially well in Sharpey's, winning gold medals in comparative and pathological anatomy. Having qualified in three years instead of the usual four, Lister then took up his first appointment as a "clinical clerk" at the hospital, while continuing to do original research of his own. His work on the microscopic structure of muscle produced his first two publications in 1853. In May of that year, he was officially awarded the Bachelor of Medicine degree (Fisher 56). By then he had been at University College for the unusually long period of ten years, and it had had a profound influence on his career.

The next part of Lister's life, the time when he built up his reputation, was spent in Scotland. He first went there to finish his studies in Edinburgh under Sharpey's friend, the distinguished Scottish surgeon James Syme. In 1854 he became Syme's house surgeon at the Edinburgh Royal Infirmary; in the following year he was elected Fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh; and on 23 April 1856 he married Syme's daughter Agnes. The choice of St George's Day was appropriate, since the Symes were Episcopalians, and it was at this time that Lister left the Society of Friends for the Church of England. It was an important move in view of his later appointment at the still highly orthodox King's. Already in 1859, Lister is on record as examining pus corpuscles from a rabbit's eye (Fisher 121), and after his first professorial appointment, as Regius Professor of Surgery at Glasgow University, the experiments he did in his spare time were focused on how best to prevent or manage the various infections that occur in hospitals. From 1861 he was surgeon to the Glasgow Infirmary, and had the opportunity of carrying his ideas through into his own surgical practice, though it was not until his attention had been drawn to Louis Pasteur's work that he really established his controversial antiseptic regime. This regime was, in effect, announced in his 1867 "Notice of a New Method of treating Compound Fractures":

we now know, thanks to the beautiful researches of Pasteur, that the active agents are not the gaseous elements of the air, but minute living organisms suspended in it, which, by developing in a decomposable substance, determine a change in its chemical arrangement analogous to the fermentation of sugar under the influence of the yeast-plant. Hence it occurred to me that if . . . a material were applied to the wound which, though it might allow the gases of the atmosphere to penetrate it, would destroy its living germs, all evil consequences might be averted. For this purpose I selected carbolic acid. [qtd. in Fisher 140]/p>

To Lister's evident delight, not only were individual surgical patients helped by germ-free healing, but the hospital environment as a whole improved, so much so that he reported that the dreaded so-called "hospital diseases" had vanished from his wards. On the crest of his success, in 1869 Lister was appointed Professor of Clinical Surgery at Edinburgh, despite having failed by one vote to get a similar appointment two years previously at his alma mater, University College London. There are some wonderful pictures of him during this period. One is of him at Balmoral, lancing a large abscess in Queen Victoria's armpit. This was during the period when he insisted on using a carbolic spray during surgery, and some had got in the Queen's eyes. When the patient complained, Sir William Jenner (1815-1898), the leading clinical consultant of the day, "replied half-jokingly that he was 'only the man who worked the bellows'" (qtd. in Truax 159) — an extraordinary tribute to the young surgeon who not so long ago had attended his lectures at University College. Another patient of that time seems more focused on the surgeon himself than on his own discomfort. This was the long-suffering William Ernest Henley, who spent about eighteen months under Lister's care in Edinburgh. In the poem "Clinical" for instance, Henley shows the professor doing the rounds with a nurse and students, "With the bright look we all know, / From the broad, white brows the kind eyes / Soothing yet nerving you...." The details here are telling: the nurse in her white uniform carries a towel, and Lister wipes his hands before moving on to the next bed, followed by his attentive audience. Acquiring a large following among both students and patients, Lister remained in Edinburgh until 1877.

Barraud's photograph of Lister. [Click on thumbnail for larger image.]

As far as London was concerned, University College's loss was to be King's College's gain. When the Professor of Surgery died at King's early that same year, Lister, now soundly Church of England, was immediately approached. After all, "his immense success in reducing mortality had caused a sensation throughout the scientific world" (Hernshaw 297), and King's College Hospital needed someone to raise its profile at that time. But neither the invitation nor its acceptance went at all smoothly. Lister's methods were pooh-poohed in the capital, where conservative surgeons still wore the same blood-splattered clothes, and used the same dirty instruments, from one operation to the next. They were confident that antiseptic precautions were only needed in more primitive places (one wonders how many people died because of this snobbish assumption). So when seven hundred of Lister's Scottish students urgently petitioned him to stay in Edinburgh, he was tempted to do so. In fact, he responded to the Scottish students' show of affection by hitting out undiplomatically against the teaching of clinical surgery in London. The attack found its way into the press, and the King's committee retaliated by recommending that the vacant Professorship should after all go to the next in line at the college. Still, negotiations continued. Fired by the desire to spread his lifesaving techniques, and looking forward to being near his remaining siblings again, Lister eventually agreed to take up an additional chair of clinical surgery at King's — but only on condition that he could bring his own surgical team with him.

Lister's struggles were far from over. On their arrival in London in 1877, the new professor and his entourage found just what they had feared. King's College Hospital had been rebuilt by Thomas Bellamy at the beginning of the 1860s, on the site of the earlier one converted from the St Clement Dane's workhouse, and was supposed to be a model hospital of its time.* Yet it was far below the standards they were used to in Scotland. Attitudes to surgical practice were entrenched, as well. At his first lecture, "On the Nature of Fermentation," Lister used milk as a medium for his demonstrations, provoking puzzlement from the surgeons in the audience, and lowing sounds from the students. In December he was still complaining that few were attending his classes, and fewer still were accompanying him on his hospital rounds. Moreover, the University of London examination system was binding, making individual research difficult. In short, "Never did his patience, his hopefulness, his interest in the cause have to submit to greater trials" (Blore 297).

Now into his fifties, Lister had never entirely thrown off a childhood stammer, had perhaps never completely recovered from the breakdown in his early twenties, and disliked being in the limelight. But he rose to the occasion. Thanks to the "faultless patience" and "unyielding will" that the poet/patient Henley had spotted in him in Edinburgh ("The Chief"), he was able to change both attitudes and practices, and the reputation of King's College Hospital soared. He too had to adapt, especially to new findings about germs — something which he did with good grace. The man who in 1858 had given a paper to the Edinburgh Surgical Society on "Spontaneous Gangrene" was now only too keen for the bacteriologist Robert Koch to make a presentation at the hospital during the landmark International Medical Congress of 1881, which met in London. He also arranged for his friend Louis Pasteur to attend. By the time Lister retired, the new germ-theory was such an important specialism that King's now had a pioneering department of bacteriology with its own professor. The college council reported in 1893 that this department attracted "a large number of zealous workers, not only from London and the provinces, but also from our colonies and from other countries" (qtd. in Hearnshaw 385). It became an important part of the faculty of medicine.

Lister Operating. [Click on thumbnail for larger image.]

The pioneer not only of antiseptics but also of various important and life-saving surgical techniques (including the use of dissolving ligatures and drainage tubes), Lister was a major force in the transformation of surgical practice and success rates during his times. "Between 1859 and 1870 hospital mortality after major operations was 45.13%: between 1886 and 1890 it was 7.1%" (Ellis 348). Of course, this was not all his doing. There were other well-trained surgeons doing innovatory, complex operations under anaesthetic, and striving to reduce the post-operative death-rate. Nursing care had improved as well, now that Florence Nightingale had raised the status of such work and turned it into a profession. More thought was going into hospital planning, especially with regard to ventilation. And as technology improved, it became possible to replace antiseptic procedures with aseptic ones (sterilisation rather than the aggressive use of potential irritants). But behind all this, Lister was still seen to be the prime mover, and rightly so. He was influential too in the intellectual life of the country as a whole, providing a figurehead for the scientific naturalism that dominated late nineteenth-century thinking. Christopher Lawrence, for example, suggests that the whole post-Darwinian drive to give science more prominence in education and society owes much to the revolution that Lister wrought in the operating theatre.

The move to London had been an astute one. For all the controversy which had surrounded him at first, Lister became very much an establishment figure. As well as being a professor at King's and a Consulting Surgeon to King's College Hospital, from 1878 he was "Surgeon in Ordinary" to Queen Victoria. In 1879 he received a rousing ovation at the International Medical Congress in Amsterdam, a sign of the growing recognition of his work abroad. He was raised to a baronetcy and became President of the Royal Society in 1883, and a peer in 1897. For the last two years of her life, he was "Serjeant-Surgeon" to the Queen, at her own insistence (an office he continued to hold for Edward VII), and he was one of the original recipients of the Order of Merit in 1902, along with such others as Lord Kitchener, the physicist Lord Rayleigh and the artist G. F. Watt. In 1903, the name of the British Institute of Preventative Medicine, which he had been instrumental in founding, was changed from the Jenner Institute to the Lister Institute. Most poignantly perhaps, the area of London which by then had swallowed up his birthplace made him an honorary "Freeman" of the city in 1907. London gloried in him at last.

Even so, Lister became rather withdrawn in later years. Despite the comfort and confidence he imparted to his patients, he had never been one of those colourful Victorian figures whose flame of life burned brilliantly. Always to some extent a Quaker at heart, he had been single-minded in the scientific pursuit of better surgical outcomes. When his wife and amanuensis Agnes succumbed to pneumonia in 1893, after accompanying him to Italy with a bad cold, it was a bitter blow. She was only fifty-seven, and the childless couple had been very close. His younger brother Arthur's death in 1907, and his own declining health, contributed to his melancholy. He finally passed away, not too soon it seems, in February 1912 at Walmer on the Kent coast, where he had spent the last few years of his life. Although there was a grand funeral service for him in Westminster Abbey, he was buried beside his wife in West Hampstead Cemetery, as he had instructed.

* The St Clement Dane's site was just a short walk from King's, but King's College Hospital later moved out to Denmark Hill in south-east London. The whole atmosphere of the Strand campus must have changed with its departure. However, the medical school gained an identity of its own, and expanded greatly. It now embraces the medical and dental schools of Guy's and St Thomas's Hospitals — making it the biggest medical school in the country. This also associates King's with another important pioneer in the medical profession, whom it had tried to attract to its own hospital in 1854: Florence Nightingale. The Nightingale Institute at St Thomas's, a part of this huge new coalition, was originally set up with funds collected for the Crimean War, and with Florence Nightingale's involvement — though at this point, according to Hugh Small, she was reluctant for such an institute to be based at King's (148-49).

Related Material

- The Listers: A Quaker family in Ipswich, England, 1840

- Pasteur and Lister: A Chronicle of Scientific Influence

- Thomas Brock's marble bust of Joseph Lord Lister

- Margaret May Giles's medallion of Joseph Lord Lister

Sources

Blore, George Henry. Victorian Worthies: Sixteen Biographies. London: Oxford UO, 1920. Available online at Project Gutenberg

Ellis, Roger. "Joseph, Lord Lister (1827-1912)." Who's Who in Victorian Britain. London: Shepheard-Walwyn, 1997. 347-48.

Fisher, Richard B. Joseph Lister 1827-1912. London: Macdonald and Jane's, 1977.

Hearnshaw, F. W. C. The Centenary History of King's College London, 1828-1928. London: Harrap, 1929.

Lawrence, Christopher. "Lister, Joseph, Baron Lister (1827-1912)." Oxford Dictionary of Literary Biography. Online ed. Viewed 1 April 2007.

Small, Hugh. Florence Nightingale: Avenging Angel. London: Constable, 1988. (Despite its title, this is very much a revisionist rather than romanticised account of its subject.)

Truax, Rhoda. Joseph Lister: Father of Modern Surgery. London: Harrap, 1947.

Last modified 11 April 2007