Apart from the first, all the photographs here are from our own website. Click on the images for larger pictures and more information; click on the links too for more information.

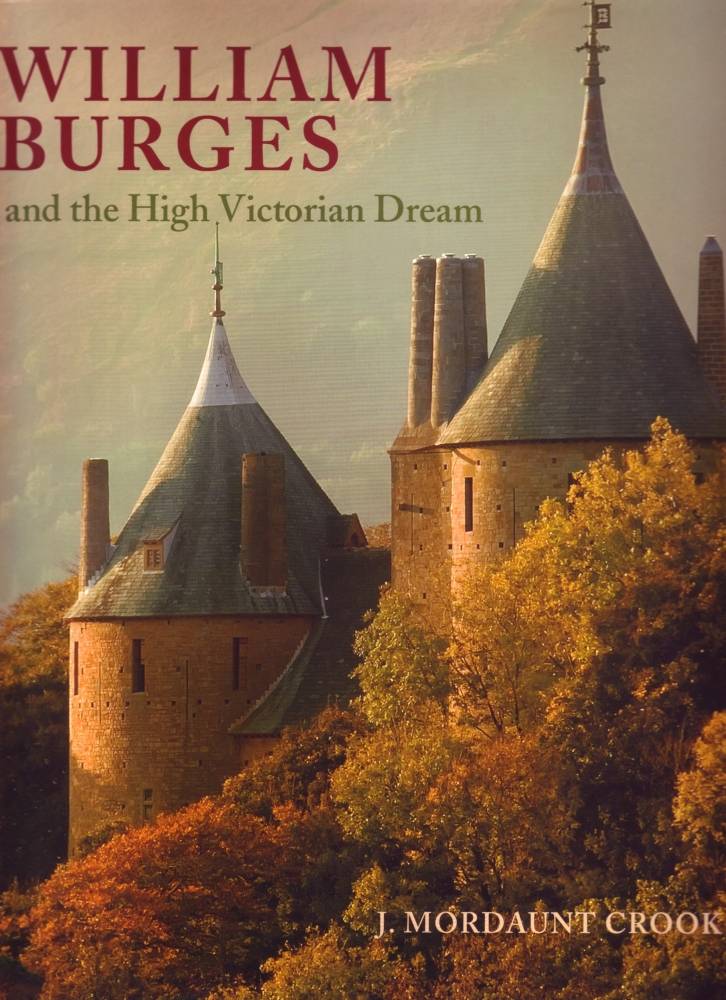

Cover of the book under review, showing "the marriage of cylinder and cone" (266) in the towers of Castel Coch, near Cardiff, which Burges rebuilt for the Marquess of Bute.

The original edition of William Burges and the High Victorian Dream was an event in itself. Published in 1981 by John Murray, it was the first full account of this brilliantly individualistic architect and designer, whose vision embraced both the medieval and the exotic; and it has remained the definitive one. There has never been another book quite like it — until now. Even this new edition, published by Francis Lincoln, is not quite like it. But this is for several good reasons. The bulk of the text is as it was in the earlier edition, and could hardly be bettered. But it has been revised and enlarged. The old "Explanation" at the beginning has been expanded into a useful preface, and the summaries of different aspects of Burges's work at the end have been pulled together nicely from the old black-and-white "Illustrations" section. The book is now fully illustrated throughout, instead of just at either end of the main text. Better still, many of the new illustrations are in colour, and the whole is on top-quality paper and in large format, with good clear print.

In the new preface, Crook introduces Burges succinctly, in all his facets, as "an art-architect: a designer with Pre-Raphaelite priorities; a three-dimensional artist in thrall to the decorative process; a builder bewitched by the Middle Ages." With his Ruskinian ideals, says Crook, Burges believed "that architecture and the applied arts are aesthetically indivisible," and saw "architecture as a vehicle for subsidiary art." In modern terms, he adds, Burges's buildings might be described "as semiotic constructs," featuring "structure as symbol; design as communication" (11). No doubt. But Burges worked on instinct and impulse, and on the full tank of a seething imagination, and labels like that seem quite alien to his work. Luckily Crook himself seems reluctant to write in this vein, and continues in the more readable way that the earlier description promises, sometimes rather arch, it is true ("Peace then, sceptical reader, as we prepare to enter the Palace of Art" 285), but always entertaining.

Partly based on his Oxford Slade lectures (1979-80), Part One of the book gives virtuoso displays of Crook's power of synthesis. The first chapter, entitled "The Dream," weaves together the various ideological strands that went into the whole idea of "medievalism as an instrument of salvation" (34). Here are the "Romantic Tories" on the one hand and the "Romantic Socialists" on the other, with Carlyle seen as a bridge between the two. These are followed by the "Romantic Artists," who took their cue from Ruskin and Morris — Rossetti and the Pre-Raphaelites, and Tennyson. Pugin figures largely in the opening section, as he should, considering his huge influence on Burges. His stock like Burges's has risen tremendously in the last thirty or so years. In fact Puginites, now more accustomed to seeing him in the context of "Romantic Catholics," might take issue with assertions that (for all his evident frustrations) he felt "trapped" in his "chosen religious community" (27), and that he only conceived the High Victorian Dream, leaving Burges to build it (34). On-going restoration work at Alton Towers and elsewhere is bringing more of Pugin's actual achievement home to us, and recent scholarship has shown us how thoroughly he created and inhabited his own dream-world at the Grange in Ramsgate.

Left two: Humorous touches at Cardiff Castle. (a) Monkeys grappling with the Book of Life, a topical joke about Darwinism. (b) A gilded crocodile lurks at the top of the Octagon staircase. Right: Parrots swoop amongst other birds painted on Lady Bute's ceiling at Castel Coch.

Burges was every bit as as idiosyncratic as his hero. Chapter Two, entitled "The Dreamer," starts prosaically enough with his family background, and moving on to his early training at King's College, London, of which he was later to be an Honorary Fellow. Then came his stints in the offices of Edward Blore, still at that time Surveyor of Westminster Abbey, and of Matthew Digby Wyatt, who usefully pointed him in the direction of the applied arts. These both had obvious bearings on his future career, as did his travels on the Continent and in Turkey and Greece. It was the impact of the Orient that made his version of the Victorian Dream more extravagant than Pugin's — for, of course, there was a development here. Here too he was introduced to Turkish baths and (probably) opium, to which from now on he would have regular recourse. His interests ranged from the more or less predictable (collecting armour, antiquities, and illuminated manuscripts), to the less so (Freemasonry and probably Rosicrucianism), and to the positively bizarre (ratting). With all that came an endearing playfulness, emphasized by Crook in a section headed "Laughing," in which he explains that visitors might be greeted at the door by this stocky near-sighted personage with a parrot on each shoulder. All this helps to explain the extraordinary mix of the precise and the fantastic in Burges's designs, as well as the diversity of his talents, and the eclectic nature of his vision.

If Chapter Two tells us all we might ever know about Burges, Chapter Three, "In Search of Style," tells us all we need to know about the architectural climate of the time — that is, the debate about how to evolve a distinctive style for the age. Enter, first, the opinionated James Fergusson, with his mantra "archaeology is not architecture" (83). His own take on "true principles" was for every age to express itself in its own way, not through tired old revivals. Gothic was anathema to him. Predictably, he liked the Crystal Palace, but the reunion of architecture and engineering that he envisaged could in fact be integrated seamlessly enough with the Gothic — think of St Pancras Station and the Grand Midland Hotel. In the other corner stood the committed Gothicists, their cudgels taken up by Alexander Beresford Hope. For a time, this pundit was nearer the mark with his pronouncement, "The only style of common-sense architecture for the future of England, must [therefore] be Gothic architecture, cultivated in the spirit of progression founded upon eclecticism" (qtd. 85). He of course hated the Crystal Palace. Battles continued to rage between architecture and engineering, archaeology and invention, and the various types of Gothic, until along came the new-old challenge of the Queen Anne style. Crook brings it all together with his usual panache.

But where did Burges stand in all this? Creating his own highly eclectic fantasies, Crook's main protagonist was hardly a protagonist here at all: "By limiting his recommendations to the practice of figure-drawing, the cult of colour, and the encouragement of the decorative arts, he shrugs off the intellectual burden, and leaves the creation of a new style to future generations." Still, says Crook, he has his place. "The creative process becomes its own justification; architecture, eating into his own world of fantasy, architecture, like any other art, sloughs off the straitjacket of utility and finds its own validity in the wider realm of aestheticism. Hence Burges's status as a link between Pre-Raphaelites and the Symbolists" (105). This is useful ammunition against those who see Burges, despite his personal gift for friendship, as rather an isolated figure, though the connection between the Gothic Revival and the Pre-Raphaelites, especially, has always been well understood: Crook himself describes the Ecclesiological Society's debate on the subject in 1860. Later, with reference to his metalwork, Crook sees Burges as "the link between the early and late Victorian periods, between the nascent medievalism of Pugin and the febrile experiments of art nouveau" (343). (Pugin's "nascent" medievalism? In the original edition, Crook had "precise," which seems much more accurate.)

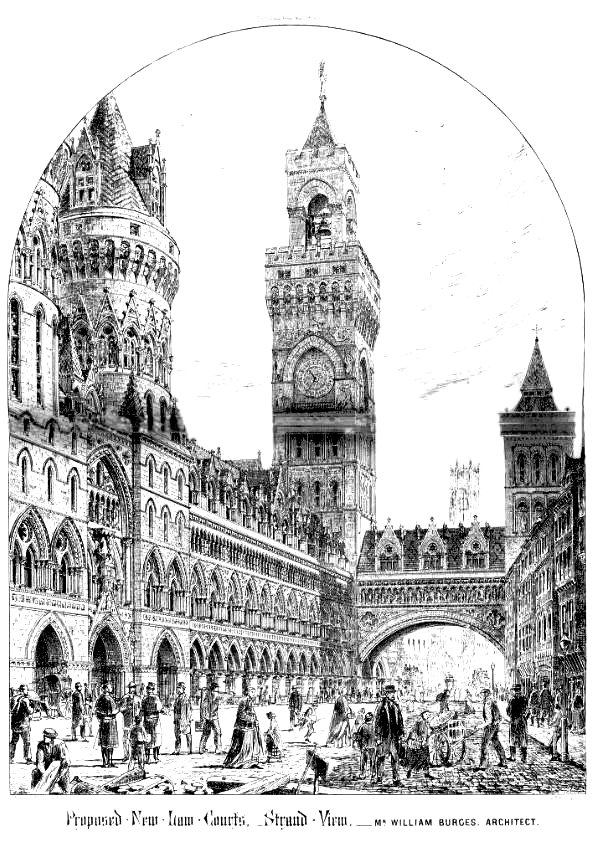

Left to right: (a) St Fin Barre's Cathedral, Cork. (b) Unrealised design for the Law Courts. (c) Tower House, Burges's own home, which he designed for himself in Kensington

But now, at last, for the oeuvre itself. Part Two consists of four chapters dealing with Burges's achievements in different areas. The first (Chapter Four) covers works such as Worcester College Hall, Oxford., in which he "wrestled with the Renaissance" (107). The second (Chapter Five, the longest) covers Burgesian Gothic. This is the "big one": The ecclesiastical works include such celebrated marvels as St Finn Barre's Cathedral, Cork, and the glorious churches at Skelton and Studley Royal, as well as "Lesser English Churches," "Smaller Irish Churches," the Ricketts Monument in Kensal Green Cemetery, and so forth. Among the secular works are the new Speech Room at Harrow, which turned out to be something of a disappointment, and, even sadder, his powerful and exotic but unrealised scheme for the Law Courts. Of the last two chapters, the Sixth, entitled "Feudal," is the one many readers will have been waiting for, on his work for the 3rd Marquess of Bute at Cardiff Castle, Castel Coch and Mount Stuart. And the last, Chapter Seven ("Fantastic"), looks at his designs for everything from bookcases to (famously) chimney-pieces, focusing on his own Tower House in Kensington. Anything not considered here — his designs for stained glass, tiles, metalwork (including jewellery), mosaics, sculptures, painted decoration and so on — has already been dealt with along the way. The appropriate sections are indicated in the preface, and some general comments about them appear in a summary at the end. What a feast!

The ceilings of what were once the dining- and drawing-rooms at Milton Court, Dorking, in Surrey. Patterns were found during refurbishment, and a Heritage Day leaflet of September 2006 explains that both were restored to Burges's original designs.

In his preface, Crook gives some telling examples of collectable items by Burges (furniture, stained glass, a silver-mounted scent-bottle) that have soared in value over the years, sometimes from practically unsaleable to practically priceless. How much this is due to his own earlier efforts to illuminate Burges's career, work and vision we can only guess. But Crook is obviously a marvellous champion to have, with a gift for summary as well as detail, and always refreshingly unpedantic. Such a reissue is more than welcome then, especially now that the earlier edition is so hard to come by. It could perhaps have done with a little more updating. For example, since 1993, the year mentioned in the appropriate endnote, further restoration work has been carried out at Milton Court, Dorking, so that more of Burges's original features there can be admired. Nevertheless, this lovely book should now find exactly what it deserves, a whole new readership primed to enjoy Crook's insights into his subject's "strange genius" (14), and indeed into its wider Victorian context .

References

(Book under review) Crook, J. Mordaunt . William Burges and the High Victorian Dream. Revised and Enlarged Edition. London: Francis Lincoln, 2013. 432pp. in large (310 x 255mm) format. £45/$75. ISBN 978-0-7112-3349-2.

Last modified 16 April 2013