which claims to be the oldest college in England, was founded by Walter de Merton, Lord High Chancellor, in 1264. Many poor scholars were already living at the expense of various benefactors in the inns or halls of which old Oxford was largely composed, but Walter de Merton was the first to found a college, and it served as a model both in the plan of its buildings and the 171 statutes by which it was governed for all other English colleges. He began by setting apart his estates in Surrey for the maintenance of some of his young kinsmen at the university, and, gradually extending his original project, he purchased some of the land upon which the college now stands and proceeded to erect buildings. His idea was that the effect of life in common upon a group of students, bound together by the same interests, yet differing in character, ability, and knowledge must be to arouse their sympathy, widen their outlook, and encourage “the reasoned conviction and independence of thought "which has ever since been the chief aim of our university education.

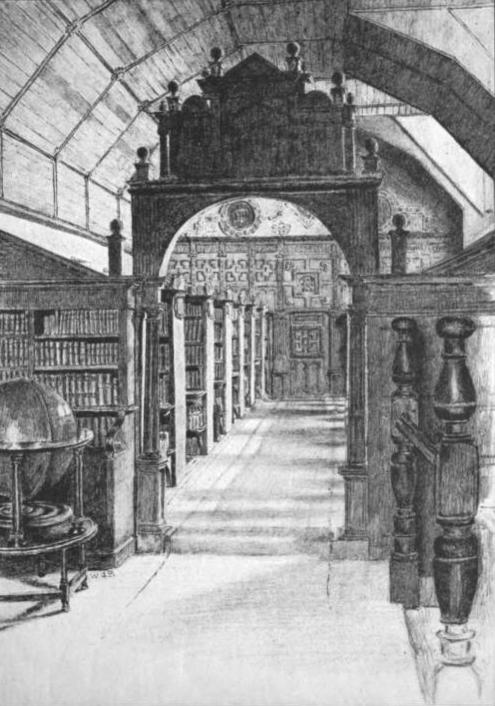

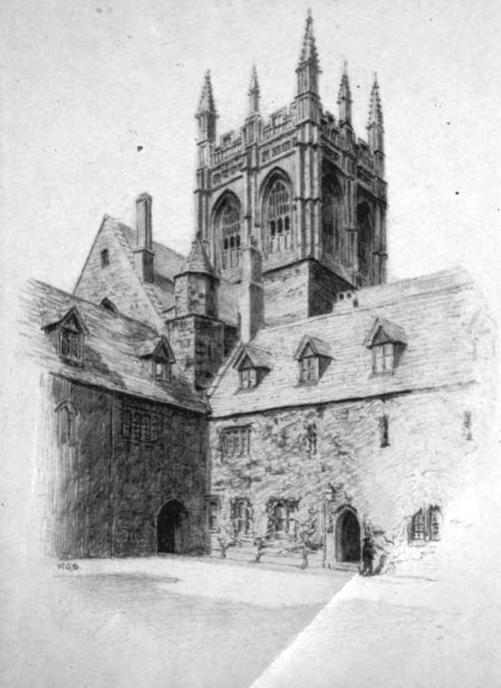

The society consisted in the first place of a warden and twenty scholars who were to be maintained for life unless they took monastic vows or committed a grave breach of discipline. They lived quietly and frugally, following a prescribed course of study; the King took an interest in their welfare, and many generous gifts increased their resources. The college buildings have of course been considerably altered and extended since those early days, but their arrangement is the same as that planned by the founder, and portions of his work still remain the chapel, a very beautiful example of thirteenth-century Decorated architecture, which was built on the site of the ancient Church of St John the Baptist, and the munimentroom with its curious highpitched stone roof under which we pass from the first quadrangle to the Mob quadrangle. In 1377, the year in which the chapel was dedicated, the founder died, but the building still went forward. The sacristy was completed in 1311, the hall in 1320, and the library, the most ancient in the kingdom, in 1349. For over a century Merton was always known as The College, not only because of its wealth and beautiful buildings but also the repute of its scholars. During that period it produced no less than six Archbishops of Canterbury, three Archbishops of Ire174 land, nine bishops, and seventeen Chancellors of the University. It was particularly renowned for such studies as mathematics, botany, and astromony; the zodiacal signs on the archway, east of the hall, leading to the fellows' quad, the dial outside the east wall of the chapel and the astrolabes in the library testify to its interest in the latter science.

Riotous Fourteenth-Century Merton Students

In the fourteenth century Oxford scholars were a turbulent and quarrelsome set, and Merton men were to be found in the thick of every fray, whether between northerners and southerners or Town and Gown. The most notable of all their battles was one in the early days of 1354 which began by a quarrel in a tavern 175 between the landlord and some students. The citizens flocked out with bows and arrows, the bells rang to arms, two thousand peasants poured in to the aid of the town, furious fighting took place, and, what with sack and fire, at the end of the third day the only refuge that remained to the students was the strong walls of Merton. The survivors of the other colleges abandoned the town for more than a year, laying it under ban and interdict, while the scholars of Merton passed their days in prayer and lamentations, “composing tragical relations in verse and prose of the conflict.”

In 1380 a second class of students was added to the college, the portionistæ or postmasters — “boys who have a stinted portion.”

Great Fifteenth- and Seventeenth-Century Leaders

The name of John à Kempis is the greatest in Merton annals in the fourteenth century. He became successively Bishop of Rochester, of Chichester, of London, Archbishop of York, Lord High Chancellor, Cardinal, and finally Archbishop of Canterbury. The west window in the south transept was his gift. The transepts of the chapel were completed in 1414, the great gateway in 1418 and the tower, the crown and glory of the college, in 1451.

Left: The Library Interior. Right: The Tower. Both W. G. Blackall. c. 1920 Source: The Charm of Oxford/ [Click on images to enlarge them.]

One of the most peaceful and prosperous periods in the history of Merton was the thirty-five years (1622) of Henry Savile's wardenship. He was the most prominent Oxonian of his time, in high favour at Court, an “extraordinary handsome and beautiful man” of whose complexion it was said “that no lady had a finer.” Courtly in manner, generous and hospitable, he attracted to Merton all the great people of the day, but his social popularity did not prevent him from devoting himself to the advancement of his college. He encouraged learning, preserved discipline and exercised special care in the elections to the fellowships with the result that the Mertonians in his time were noted for their brilliant scholarship. One of the chief of them was Sir Thomas Bodley, the founder of the Bodleian Library, to which the college contributed many books; he died in 1613 and his body was brought from London to Oxford and interred in Merton Chapel in the north-east corner of the choir. The whole university turned out to pay him the last respects, and every member of Merton joined in the great funeral procession through the streets of Oxford.

Savile was a distinguished Greek scholar and one of the translators of the Authorised Version of the Bible ; he founded the Savilian Professorships of Geometry and Astronomy, which greatly stimulated the study of those sciences in the university. He was also the head of Eton College and on the monument erected to his memory in Merton Chapel are sculptured pictures of his two colleges. In his time the front of the college, from the porter's lodge to the warden's house, was entirely rebuilt, the dormer windows were added to the library, and the fellows' quadrangle, the most beautiful in Oxford, was built.

In 1638 Archbishop Laud, who on his election as chancellor had commenced “to reforme the university which was extremely sunk from all discipline and fallen into all licentiousness,” turned his attention to Merton ; when his visitors arrived each member of the college was called before them and required to render an account not only of his religious beliefs and intellectual proficiency but also of the 180 smallest details of his everyday life. When the visitation was concluded, Laud issued thirty-six injunctions, some of which have effect even in the present day, and bear witness to his honest wisdom, but his interference in the government of the college aroused a hostile feeling which told against him at his trial.

Merton in the Eighteenth-Century

At the beginning of the eighteenth century the chief pleasure resort in the university was Merton College Garden, then open all day to the public, the undergraduates lavishly entertaining their friends. A chronicler of the day writes : “I am not the only one that has taken notice of the almost universal corruption of our youth which is to be imputed to nothing so much as to that multitude of Female Residentiaries who have of late infested our learned retirements and drawn off numbers of unwary young persons from their studies.” At last the matter became such a public scandal that the garden was 183 closed altogether to the public. The Earl of Malmesbury wrote of Merton in the eighteenth century: “ The two years of my life I look back to as most unprofitably spent were those I passed at Merton. The discipline of the university happened also at this particular moment to be so lax that a gentleman commoner was under no restraint and never called upon to attend either lecture or chapel or Hall. My tutor, an excellent and worthy man, according to the practice of all tutors at that moment, gave himself no concern about his pupils, I never saw him but once during a fortnight. ... The set of men with whom I lived were very pleasant but very idle fellows. Our life was an imitation of high life in London.”

Nineteenth-Century Reforms

In the middle of the nineteenth century reforms were set on foot in Merton and the code of statutes drawn up under which it is now governed. In 1850 the roof of the chapel received its present decoration, in 1864 the new building, reached through an archway at the north-west angle of the quadrangle, was built for the accommodation of additional students, in 1872 the hall was reconstructed by Sir Gilbert Scott, and in 1882 St Alban Hall, dating back to 1220, became part of the college, a subway was made connecting the two and it now forms the fourth quad. The garden at Merton is rendered 185 particularly attractive by the terrace walk on a portion of the old city wall, from which a beautiful view may be obtained across the meadows.[179-86]

On leaving Merton we cross the street to the right and proceeding up Logic Lane to the High find Queen's College facing us on the opposite side of the road. [171-87]

Bibliography

Wells, J. The Charm of Oxford. Illustrated by W. G. Blackall. 2nd ed. London: Simpkin, Marshall, Hamilton Kent & Co., [c.1920]. Internet Archive version of a copy in St. Michael's College Toronto. 3 October 2012.

Lang, Elsie M. The Oxford Colleges. London: T. Werner. HathiTrust online version of a copy in the University of Michigan Library. Web. 8 November 2022.

Last modified 30 November 2022