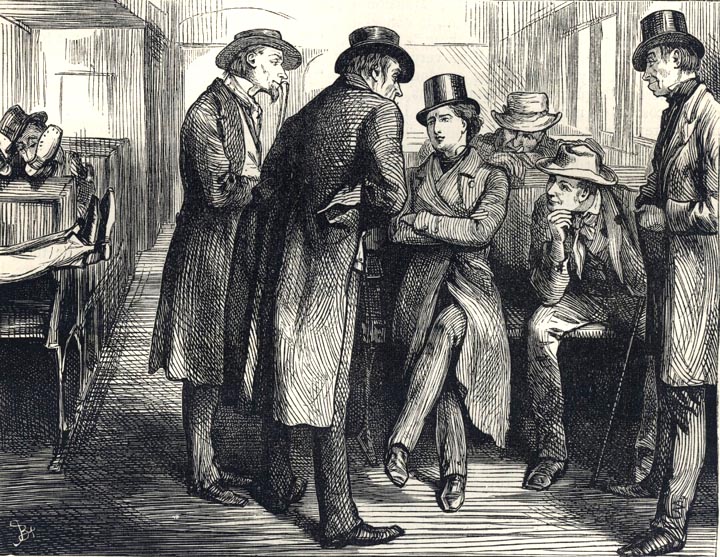

"I was merely remarking, gentlemen — though it's a point of very little import — that the Queen of England does not happen to live in the Tower of London." (1872). — Fred Barnard's twenty-seventh illustration for Dickens's Martin Chuzzlewit, (Chapter XXI), page 177. [In Dickens's satire of the generally ill-informed nature of Americans with respect to Europe, Martin corrects his acquaintances' peculiar notions about the British monarchy and such iconic sites as the Tower of London.] 10.8 cm x 13.7 cm. Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Passage Illustrated

Mr. Kettle bowed.

"In the name of this company, sir, and in the name of our common country, and in the name of that righteous cause of holy sympathy in which we are engaged, I thank you. I thank you, sir, in the name of the Watertoast Sympathisers; and I thank you, sir, in the name of the Watertoast Gazette; and I thank you, sir, in the name of the starspangled banner of the Great United States, for your eloquent and categorical exposition. And if, sir," said the speaker, poking Martin with the handle of his umbrella to bespeak his attention, for he was listening to a whisper from Mark; "if, sir, in such a place, and at such a time, I might venture to con-clude with a sentiment, glancing — however slantin'dicularly — at the subject in hand, I would say, sir may the British Lion have his talons eradicated by the noble bill of the American Eagle, and be taught to play upon the Irish Harp and the Scotch Fiddle that music which is breathed in every empty shell that lies upon the shores of green Co-lumbia!"

Here the lank gentleman sat down again, amidst a great sensation; and every one looked very grave.

"General Choke," said Mr. La Fayette Kettle, "you warm my heart; sir, you warm my heart. But the British Lion is not unrepresented here, sir; and I should be glad to hear his answer to those remarks."

"Upon my word," cried Martin, laughing, "since you do me the honour to consider me his representative, I have only to say that I never heard of Queen Victoria reading the What's-his-name Gazette and that I should scarcely think it probable."

General Choke smiled upon the rest, and said, in patient and benignant explanation:

"It is sent to her, sir. It is sent to her. Per mail."

But if it is addressed to the Tower of London, it would hardly come to hand, I fear," returned Martin, "for she don't live there."

"The Queen of England, gentlemen," observed Mr. Tapley, affecting the greatest politeness, and regarding them with an immovable face, "usually lives in the Mint to take care of the money. She has lodgings, in virtue of her office, with the Lord Mayor at the Mansion House; but don't often occupy them, in consequence of the parlour chimney smoking." — Chapter 21, "More American experiences, Martin takes a partner, and makes a purchase. Some account of Eden, as it appeared on paper. Also of the British Lion. Also of the kind of sympathy professed and entertained by the Watertoast Association of United Sympathisers," p. 177-178.

Commentary

The scene on the railway car as Martin and Mark make their way to the absurdly-named Eden on the banks of the Mississippi (which becomes in Mark Twain's Adventures of Huckleberry Finn in 1886 the town of Cairo, a possible destination for the runaways that constitutes freedom from slavery) sets up the satire on American "learned" and patriotic societies of amateurs such as the Watertoast Association of United Sympathisers, Anglophobic and pro-Irish (as the reference to the Irish Harp would suggest).

While several travellers sleep on the hard, wooden seats with their feet indecorously displayed (left), Barnard's American gentlemen crowd around Martin (top-hat) and Mark (soft hat) to query the young Englishmen about Queen Victoria's residences. Barnard makes Martin look perfectly serious in stylish topcoat, while Mark has a bemused smile that communicates the artist's attitude towards his material. Refreshingly, Americans in these episodes feel no reticence in engaging perfect strangers in conversation if they are seeking information about foreign places and persons. Here, however, Dickens makes them thoroughly gullible as he has Mark pass off spurious observations about the Mint and Mansion House, much to the delight of contemporary English readers.

Relevant Images of the Young Englishmen among the Americans, 1843-1910

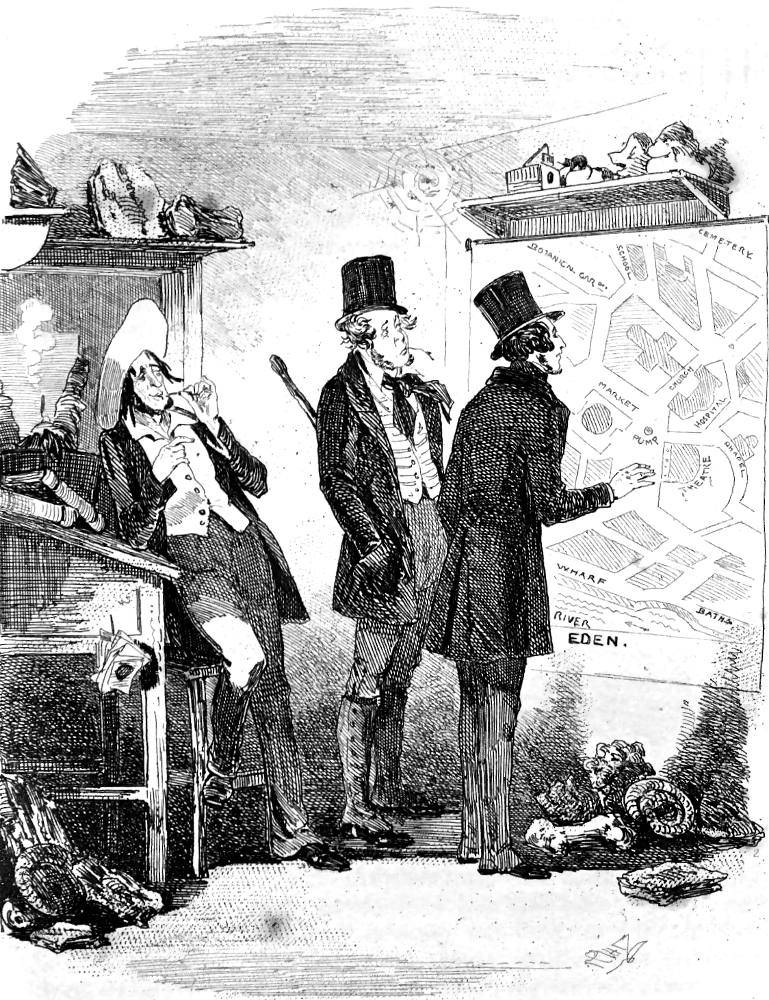

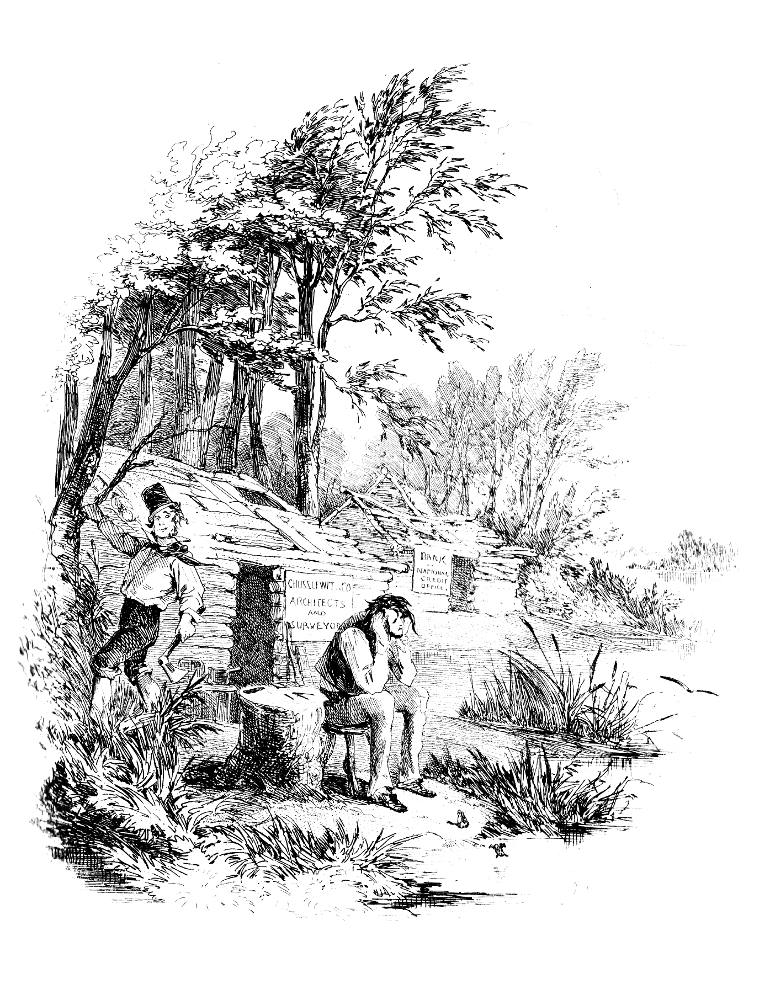

Left: Hablot Knight Browne's initial view of Eden — on the wall of the land agent's office, The Thriving City of Eden as it Appeared on Paper (Chapter 21, September 1843). Right: Phiz's support of Dickens's satire of the actual appearance of the mosquito-infested wilderness, The Thriving City of Eden as it Appeared in Fact (September 1843). [Click on images to enlarge them.]

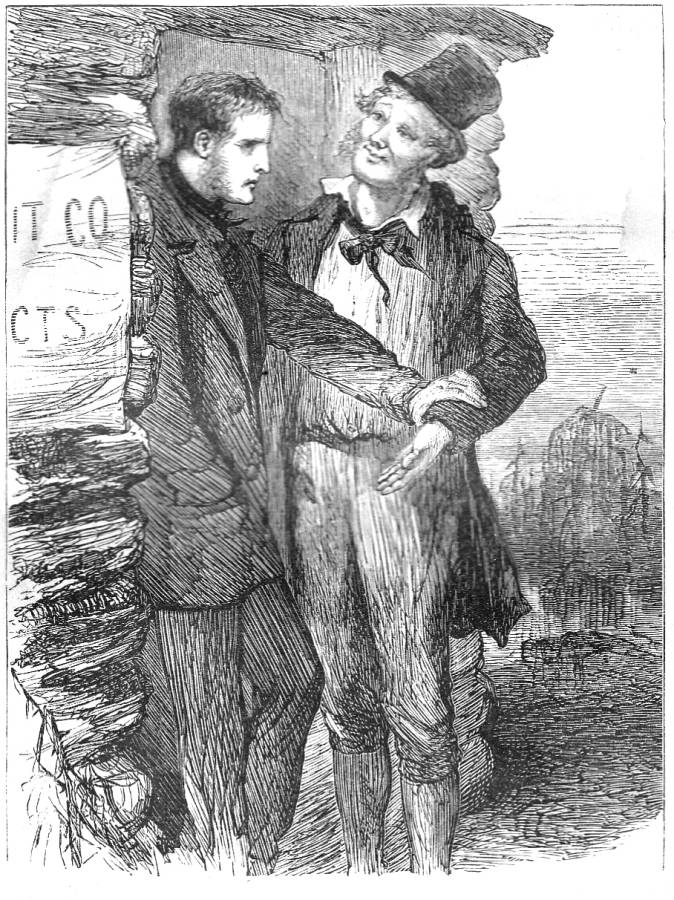

Left: Sol Eytinge, Jr.'s study of the effect of the place on Martin, Martin Chuzzlewit and Mark Tapley outside their plague-infested cabin in the mournful wilderness of the Mississippi valley (1867). Right: Harry Furniss's contrasting visions of the ebullient Mark Tapley and the dilapidated cabins that constitute the ironically-named Eden, "Eden!" (1910).[Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Above: Fred Barnard's realisation of the scene in which Martin is invited to deliver a lecture to the Watertoast Society, "Well, sir!" said the Captain, putting his hat a little more on one side, for it was rather tight in the crown: "You're quite a public man I calc'late."(1872). [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

References

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. New York and Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1990.

Dickens, Charles. The Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit. Illustrated by Hablot Knight Browne. London: Chapman and Hall, 1844.

_____. Martin Chuzzlewit. Works of Charles Dickens. Household Edition. 55 vols. Il. F. O. C. Darley and John Gilbert. New York: Sheldon and Co., 1863. Vol. 2 of 4.

_____. The Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Junior. The Diamond Edition. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

_____. The Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit, with 59 illustrations by Fred Barnard. Household Edition, volume 2. London: Chapman and Hall, 1871-1880. The copy of the Household Edition from which this picture was scanned was the gift of George Gorniak, proprietor of The Dickens Magazine, whose subject for the fifth series, beginning in January 2008, was this novel.

_____. Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book, 1910. Vol. 7.

Kyd [Clayton J. Clarke]. Characters from Dickens. Nottingham: John Player & Sons, 1910.

Steig, Michael. "Martin Chuzzlewit's Progress by Dickens and Phiz. Dickens Studies Annual 2 (1972): 119-149.

Last modified 24 July 2016