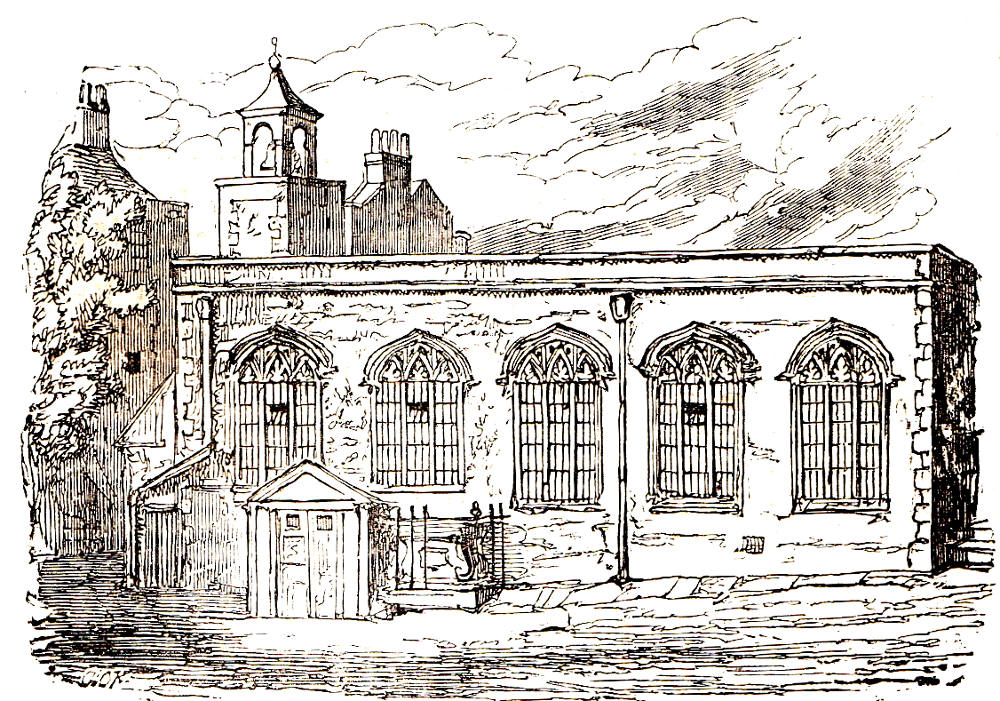

South view of St. Peter's Chapel on the Green. — George Cruikshank. Eighth instalment, August 1840 number. Fifty-ninth illustration and thirty-fourth wood-engraving in William Harrison Ainsworth's The Tower of London. A Historical Romance. Illustration for Book the Second, Chapter XIX. 6.7 cm high x 9.3 wide, vignetted, p. 256: running head, "The Stake." [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Passage Complemented

On the night before this terrible sentence was carried into effect, he was robed in a loose dress of flame-coloured taffeta, and conveyed through the secret passages to Saint John’s Chapel in the White Tower, which was brilliantly illuminated, and filled with a large assemblage. As he entered the sacred structure, a priest advanced with holy water, but he turned aside with a scornful look. Another, more officious, placed a consecrated wafer to his lips, but he spat it out; while a third forced a couple of tapers into his hands, which he was compelled to carry, in this way, he was led along the aisle by his guard, through the crowd of spectators who divided as he moved towards the altar, before which, as on the occasion of the Duke of Northumberland’s reconciliation, Gardiner was seated upon the faldstool, with the mitre on his head. Priests and choristers were arranged on either side in their full habits. The aspect of the chancellor-bishop was stern and menacing, but the miserable enthusiast did not quail before it. On the contrary, he seemed inspired with new strength; and though he had with difficulty dragged his crippled limbs along the dark passages, he now stood firm and erect. His limbs were wasted, his cheeks hollow, his eyes deep sunken in their sockets, but flashing with vivid lustre. At a gesture from Gardiner, Nightgall and Wolfytt, who attended him, forced him upon his knees.[Chapter XX. — "How Edward Underhill was burnt on Tower Green," p.252-53]

The place appointed as the scene of his last earthly suffering was a square patch of ground, marked by a border of white flint stones, then, and even now, totally destitute of herbage, in front of Saint Peter’s Chapel on the Green, where the scaffold for those executed within the Tower was ordinarily erected, and where Anne Boleyn and Catherine Howard were beheaded. [Chapter XX. — "How Edward Underhill was burnt on Tower Green," p.253]

Commentary

The place at which Edward Underhill meets his death was the site of a number of other executions, to which a plaque now bears testimony. In addition to the two wives of Henry VIII to whom Ainsworth alludes, executed on 19 May 1836 and 13 February 1542, at a scaffold on that spot the following members of the nobility met their deaths: William, Lord Hastings (June 1483); Margaret, Countess of Salisbury (27 May 1541); Jane, Viscountess Rochford (13 February 1842); Lady Jane Grey (12 February 1554); and Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex (15 February 1601).

However, all of these members of the nobility fell under the blade of the headsman's axe, except for Anne Boleyn, whose head was severed by a French executioner's sword. Such an execution as Underhill's would hardly have been conducted within the precincts of the Tower of London. Moreover, as a traitor or one guilty of sedition (for he had made an attempt on the Queen's life), he would probably have been hanged, drawn, and quartered. No heretic was ever burned at the stake on Tower Green, although Mary certainly ordered the immolation of a number of leading Protestants. The sheer scale of the slaughter of Protestants of all degrees is remarkable: between the beginning of 1555 and the close of 1558 some 284 people of various social backgrounds met their deaths at the stake under Bloody Mary's edicts. Another nine Protestants were exhumed and burned, so virulent was Mary's persecution. Perhaps as many as 300 Protestants met their deaths at the stake during the five years of Mary I's reign in what historians have termed "The Marian Persecution" — but among these none bore the name Edward Underhill, who is therefore a purely fictional character in Ainsworth's historical romance.

Other Scenes at St. Peter's Chapel on the Green

Above: Cruikshank's grisly steel-engraving of the execution of Edward Underhill near St. Peter's Chapel The Burning of Edward Underhill on the Tower Green. (August 1840) [Click on image to enlarge it.]

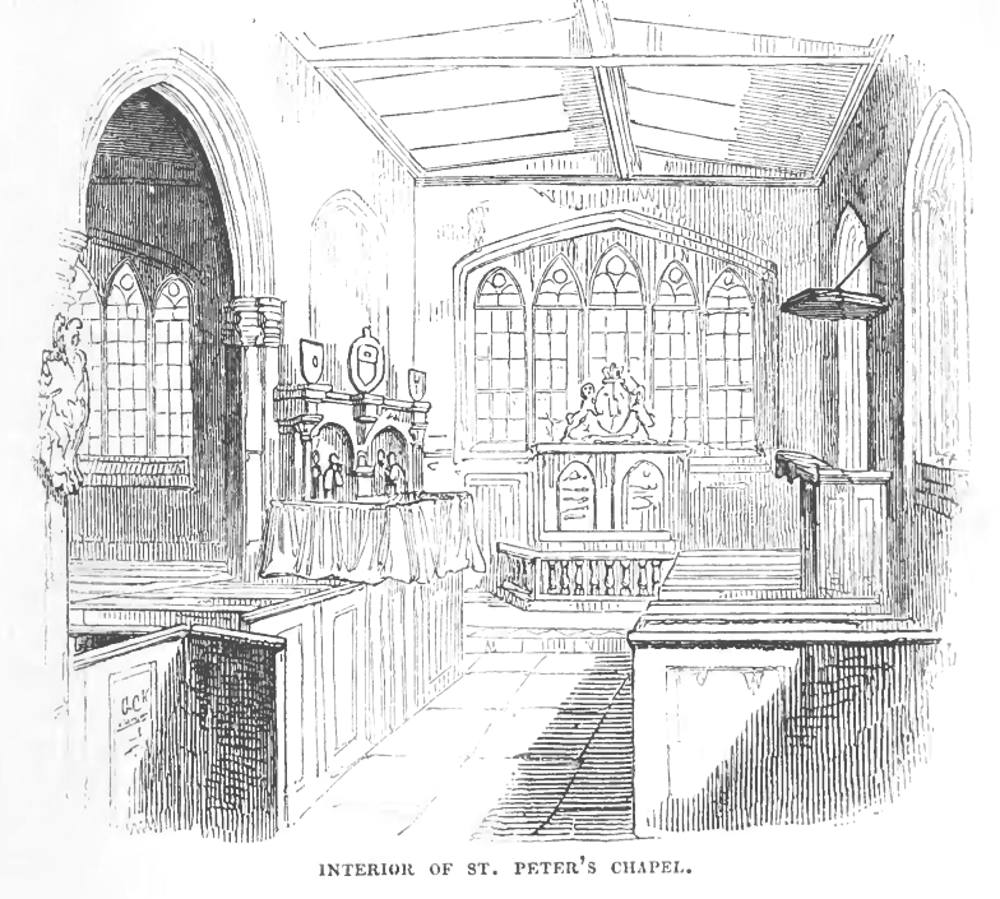

Above: Cruikshank's earlier wood-engraving of the quiet interior of the Chapel as it appeared in 1840, Interior of St. Peter's Chapel. (February 1840) [Click on image to enlarge it.]

The Chapel of St. Peter ad Vincula

The interior of St. Peter's was the scene of Queen Jane's asserting her authority over the fractious Duke of Northumberland and the Machiavellian Spanish ambassador, in Queen Jane interposing between Northumberland and Simon Renard (steel-engraving, March 1840) in Book the First, Chapter X. Ainsworth has already provided an antiquarian discussion of this significant setting in Book One, Chapter 10:

Erected in the reign of Edward the First, the little chapel of St. Peter ad Vincula (the parochial church — for the Tower, it is almost needless to say, is a parish in itself), is the second structure occupying the same site and dedicated to the same saint. The earlier fabric was much more spacious, and contained two chancels, with stalls for the king and queen, as appears from the following order for its repair issued in the reign of Henry the Third, and recorded by Stow: — The king to the keepers of the Tower work, sendeth greeting: We command you to brush or plaster with lime well and decently the chancel of St. Mary in the church of St. Peter within the bailiwick of our Tower of London, and the chancel of St. Peter in the same church; and from the entrance of the chancel of St. Peter to the space of four feet beyond the stalls made for our own and our queen’s use in the same church; and the same stalls to be painted. And the little Mary with her shrine and the images of St. Peter, St. Nicholas, and Katherine, and the beam beyond the altar of St. Peter, and the little cross with its images to be coloured anew, and to be refreshed with good colours. And that ye cause to be made a certain image of St. Christopher holding and carrying Jesus where it may best and most conveniently be done, and painted in the foresaid church. And that ye cause two fair tables to be made and painted of the best colours concerning the stories of the blessed Nicholas and Katherine, before the altars of the said saints in the same church. And that ye cause to be made two fair cherubims with a cheerful and joyful countenance standing on the right and left of the great cross in the said church. And moreover, one marble font with marble pillars well and handsomely wrought."

Thus much respecting the ancient edifice. The more recent chapel is a small, unpretending stone structure, and consists of a nave and an aisle at the north, separated by pointed arches, supported by clustered stone pillars of great beauty. Its chief interest is derived from the many illustrious and ill-fated dead crowded within its narrow walls. [Book One, Chapter X. — "How the Duke of Northumberland Menaced Simon Renard in Saint Peter's Chapel on the Tower-Green; and How Queen Jane Interposed Between Them," pp. 72-73]

Bibliography

"Ainsworth, William Harrison." http://biography.com

Ainsworth, William Harrison. The Tower of London. Illustrated by George Cruikshank. London: Richard Bentley, 1840.

Burton, Anthony. "Cruikshank as an Illustrator of Fiction." George Cruikshank: A Revaluation. Ed. Robert L. Patten. Princeton: Princeton U. P., 1974, rev., 1992. Pp. 92-128.

Carver, Stephen. Ainsworth and Friends: Essays on 19th Century Literature & The Gothic. 11 September 2017.

Department of Environment, Great Britain. The Tower of London. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office, 1967, rpt. 1971.

Chesson, Wilfred Hugh. George Cruikshank. The Popular Library of Art. London: Duckworth, 1908.

Golden, Catherine J. "Ainsworth, William Harrison (1805-1882." Victorian Britain: An Encyclopedia, ed. Sally Mitchell. New York and London: Garland, 1988. Page 14.

Kelly, Patrick. "William Harrison Ainsworth." Dictionary of Literary Biography, Vol. 21, "Victorian Novelists Before 1885," ed. Ira Bruce Nadel and William E. Fredeman. Detroit: Gale Research, 1983. Pp. 3-9.

McLean, Ruari. George Cruikshank: His Life and Work as a Book Illustrator. English Masters of Black-and-White. London: Art and Technics, 1948.

Pitkin Pictorials. Prisoners in the Tower. Caterham & Crawley: Garrod and Lofthouse International, 1972.

Sutherland, John. "The Tower of London" in The Stanford Companion to Victorian Fiction. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 19893. P. 633.

Steig, Michael. "George Cruikshank and the Grotesque: A Psychodynamic Approach." George Cruikshank: A Revaluation. Ed. Robert L. Patten. Princeton: Princeton U. P., 1974, rev., 1992. Pp. 189-212.

Vogler, Richard A. Graphic Works of George Cruikshank. Dover Pictorial Archive Series. New York: Dover, 1979.

Worth, George J. William Harrison Ainsworth. New York: Twayne, 1972.

Vann, J. Don. "The Tower of London, thirteen parts in twelve monthly instalments, January-December 1840." Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: MLA, 1985. Pp. 19-20.

Last modified 20 October 2017