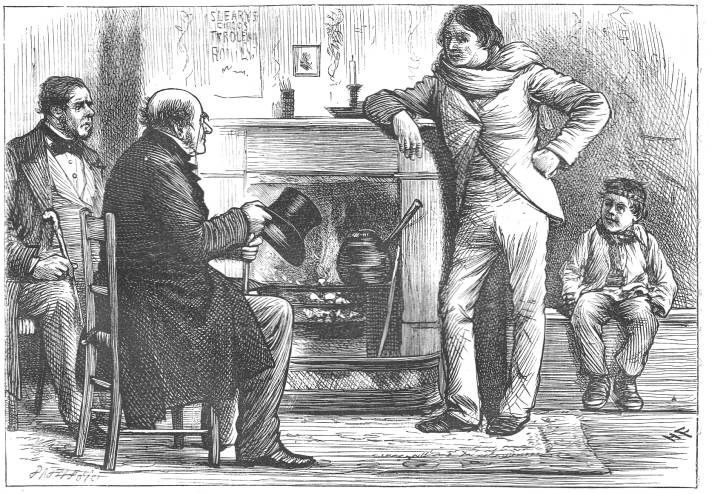

"'This Is a Very Obtrusive Lad!' Said Mr. Gradgrind" by Harry French. Wood engraving. 1870s. 13.9 cm wide x 9.6 cm high. This llustration for Dickens's Hard Times for These Times appears in the British Household Edition, p.16. 4. It depicts Thomas Gradgrind, Josiah Bounderby, E. W. B. Childers, and Master Kidderminster (otherwise, "Cupid") in Sissy's room at the Pegasus's Arms (Book I, Ch. 6).

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

The Circus Folk and the Capitalists — Artifice vs. Sham:

"There is even an inverted similarity in their most extreme pretenses: Kidderminster pretends to be Childer's [sic] son; Bounderby pretends not to be his mother's child." [Catherine Gallagher, 162]

Plate No. 4, depicting the meeting of Gradgrind, Bounderby, Childers, and Kidderminster at the Pegasus's Arms, visually integrates these disparate plot-lines, following up on Gradgrind's dragging his children away from the circus in Plate 3. Thematically, the plate connects the made-up, theatrical world of the circus performers with the false front of The Bully of Humility, the supposedly "self-made man" Bounderby. (The circus lingo in which Childers and Kidderminster express their mutual contempt for Bounderby Dickens borrowed from his friend Mark Lemon, editor of Punch.)

The scene also hints at the unnaturalness of the sort of asexual reproduction that Bounderby indulges in at the conclusion of the novel. We might expect Dickens, something of a Capitalist himself by 1854 as a major stakeholder in the weekly magazine Household Words, to side with Bounderby and Gradgrind. However, since the theatre was always in his blood, it should come as no surprise that he sides instead with Childers, who sees through Bounderby's imposture. The dwarf Kidderminster's artifice as Cupid (for he is no child at all) is harmless entertainment for the masses; in contrast, Bounderby's puffery about his ditch-water origins is part of his technique for enslaving his workers, keeping their demands in line with his spartan childhood. Both antagonists in the argument are motivated by pecuniary considerations, of course.

References

Gallagher, Catherine. The Industrial Reformation of English Fiction 1832-1867. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1985.

Created 17 April 2002

Last modified 25 December 2019