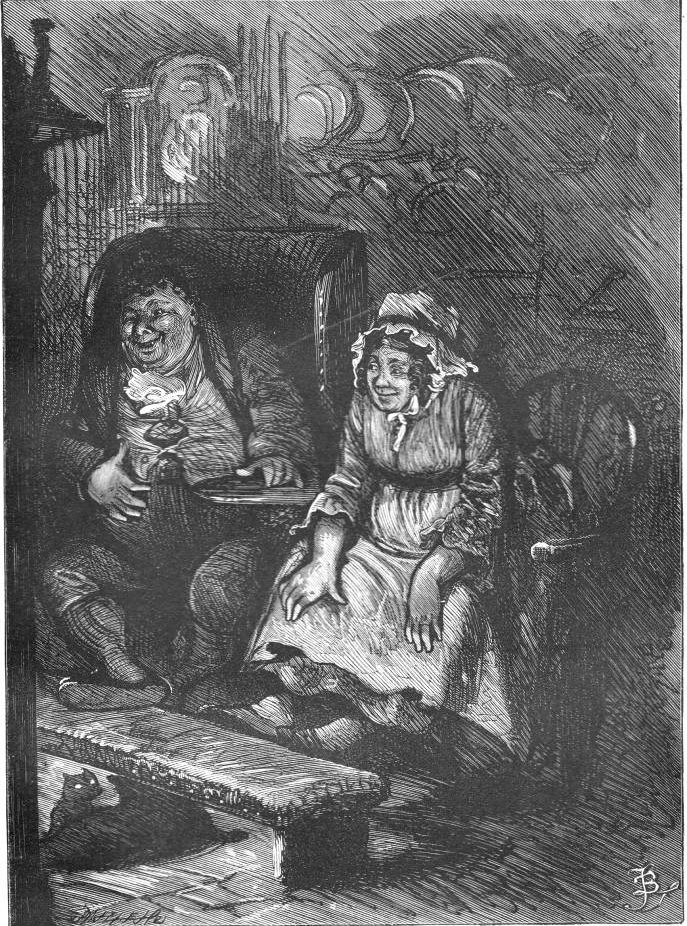

Mrs. Tugby's Visitor by Charles Green (p. 121). 1912. 11 x 13.6 cm, exclusive of frame. Dickens's The Chimes, Pears Centenary Edition, in which the plates often have captions that are different from the titles in the "List of Illustrations" (p. 15-16). Specifically, Mrs. Tugby's Visitor has a lengthy caption that is quite different from its title in the "List of Illustrations"; the textual quotation that serves as the caption for this illustration of the supercilious young parish physician conferring with Mrs. Tugby about the failing health of her back-attic tenant (in fact, Richard) is "Now then!" said that lady, passing out into the little shop. "What's wanted? Oh! I beg your pardon, sir, I'm sure. I didn't think it was you" ("Fourth Quarter," 120 — the passage realised is at the bottom of the previous page, immediately opposite the illustration, which occupies two-thirds of page 121). There is no equivalent illustration in the 1844 first edition of the novella.

Passage Illustrated

Attentive to the rattling door, Mrs. Tugby had already risen.

"Now then!" said that lady, passing out into the little shop. "What's wanted? Oh! I beg your pardon, sir, I'm sure. I didn't think it was you."

She made this apology to a gentleman in black, who, with his wristbands tucked up, and his hat cocked loungingly on one side, and his hands in his pockets, sat down astride on the table-beer barrel, and nodded in return.

"This is a bad business up-stairs, Mrs. Tugby," said the gentleman. "The man can't live."

"Not the back-attic can't!" cried Tugby, coming out into the shop to join the conference.

"The back-attic, Mr. Tugby," said the gentleman, "is coming downstairs fast, and will be below the basement very soon."

Looking by turns at Tugby and his wife, he sounded the barrel with his knuckles for the depth of beer, and having found it, played a tune upon the empty part.

"The back-attic, Mr. Tugby," said the gentleman: Tugby having stood in silent consternation for some time: "is Going."

"Then," said Tugby, turning to his wife, "he must Go, you know, before he's Gone."

"I don't think you can move him," said the gentleman, shaking his head. "I wouldn't take the responsibility of saying it could be done, myself. You had better leave him where he is. He can't live long." ["Fourth Quarter," 120-22, 1912 edition]

Commentary

The physician with the casual attitude of Dick Swiveller from The Old Curiosity Shop (1841) is hardly sympathetic to the sufferings lodger in the back-attic, Richard, although he is certainly curious about Richard's relationship with Meg; on the other hand, Mrs. Tugby, remembering what a fine, manly youth Richard used to be before Trotty's death, is distressed to hear about his decline. Although the substantial groceress does not seem to be distressed, Green has captured the essence of her business, well stocked and orderly. Above this scene of mercantile affluence, Richard, brought low by alcoholism, is dieing. Had he known the consolation of home and family, had he as young man married Meg rather than, following the advice of the Malthusian statistician, Alderman Cute's associate, Filer, he would have had reason to work industriously and live optimistically, knowing Meg would be waiting for him at the end of each day's labour. Thus, Dickens uses an emotional appeal rather than a rationale argument to refute the contention of Malthus and the Benthamites that the only hope for humanity against the cataclysmic rise in population that was inevitable was delayed procreation amongst the masses — otherwise, humanity would increase exponentially, its sources of sustenance only arithmetically (the thesis of the Reverend Thomas Malthus's Essay on the Principle of Population, 1798), the second edition of which (1803) posited the solution of "moral restraint": "Perhaps the masses of people, who bore the brunt of the hunger that was built into Creation, could be educated or coerced to limit their own numbers and thus dispense the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse from the necessity of the doing the job for them" (Altick, 121]).

Here, Dickens reveals that the Malthusian solution of delaying marriage among the working poor is hardly calculated to produce happy, fulfilling lives among the masses, whom the radical novelists represents in the particular with decent, morally upright young proletarians as Meg and Richard, to whose characters the compassionate Mrs. Tugby attests in this scene. Green sees her as far more than a caricature: a thoughtful, caring member of the middle class who believes in the right of the working class to lead happy, productive lives.

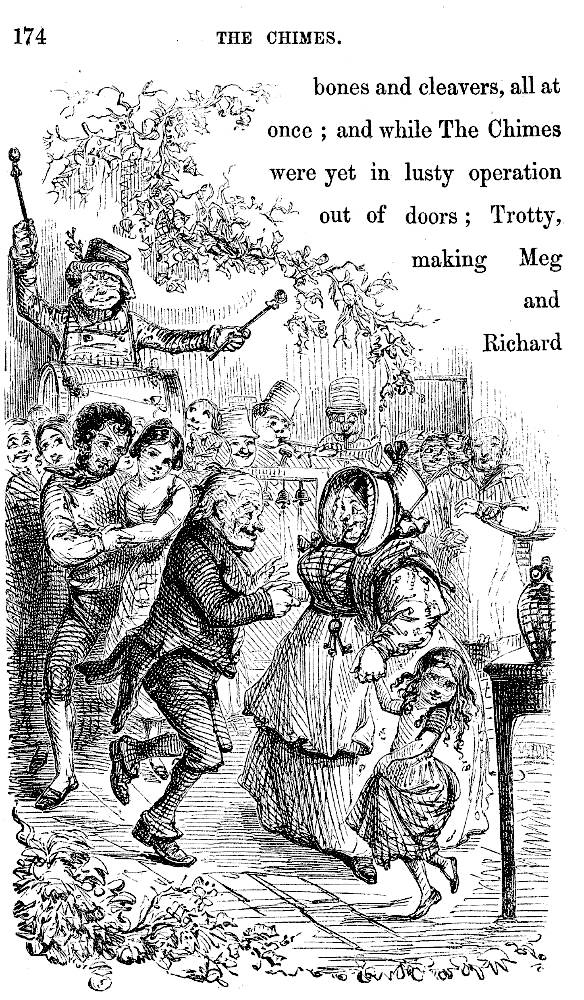

Illustrations from the first edition (1844) and the British Household Edition (1878)

Left: Leech's's study of Mrs. Chickenstalker, dancing with Trotty at Meg's wedding, The New Year's Dance. Right: Barnard's less flattering characterization of Mrs. Tugby, "You're in spirits, Tugby, my dear."

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Altick, Richard D. "IV. The Utilitarian Spirit." Victorian People and Ideas: A Companion for the Modern Reader of Victorian Literature. London and New York: W. W. Norton, 1973.

Dickens, Charles. The Chimes. Introduction by Clement Shorter. Illustrated by Charles Green. The Pears' Centenary Edition. London: A & F Pears, [?1912].

_____. The Chimes: A Goblin Story of Some Bells That Rang An Old Year Out and a New Year In. Illustrated by John Leech, Richard Doyle, Clarkson Stanfield, and Daniel Maclise. London: Bradbury and Evans, 1844.

_____. The Chimes: A Goblin Story of Some Bells That Rang An Old Year Out and a New Year In. Illustrated by John Leech, Richard Doyle, Clarkson Stanfield, and Daniel Maclise. (1844). Rpt. in Charles Dickens's Christmas Books, ed. Michael Slater. Hardmondsworth: Penguin, 1971, rpt. 1978. 137-252.

_____. Christmas Books. Illustrated by E. A. Abbey. The Household Edition. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1876.

_____. Christmas Books. Illustrated by Fred Barnard. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1878.

_____. Christmas Books. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. London: Educational Book, 1910.

Solberg, Sarah A. "'Text Dropped into the Woodcuts': Dickens' Christmas Books." Dickens Studies Annual 8 (1980): 103-18.

Thomas, Deborah A. Dickens and The Short Story. Philadelphia: U. Pennsylvania Press, 1982.

Welsh, Alexander. "Time and the City in The Chimes." Dickensian 73, 1 (January 1977): 8-17.

Created 14 April 2015

Last modified 25 February 2020