Originally written for the Journal of the Royal Society of Painter-Etchers and Engravers, where it appeared in No 11 (January 1990), this article is reproduced here by kind permission of the author, who was a long-time editor of the journal. Also with permission, it has been slightly edited and arranged for our website, and illustrated with examples of the work shown in Pennell's Adventures of an Illustrator. — Jacqueline Banerjee.

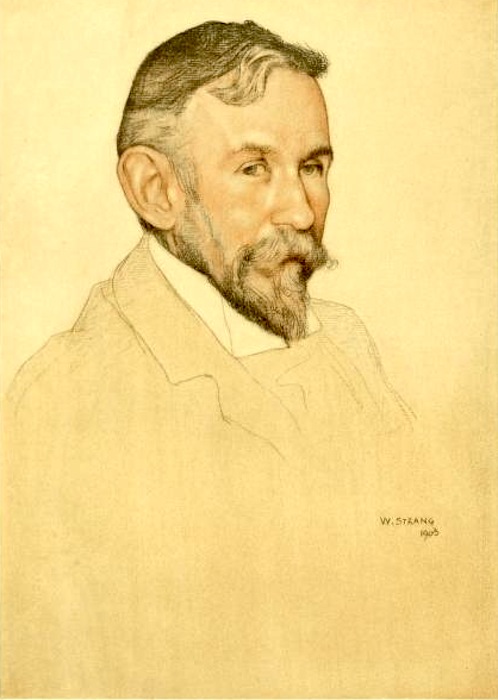

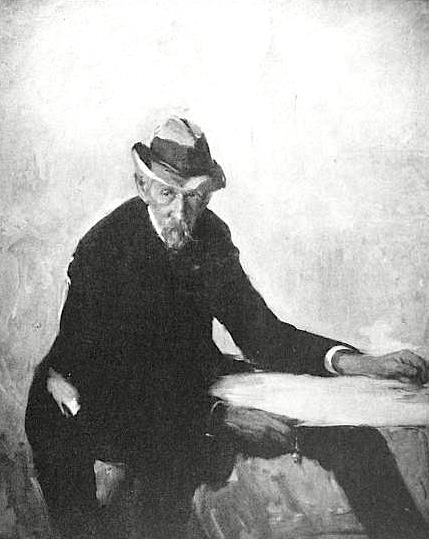

Two portraits of Joseph Pennell from his Adventures of an Illustrator. Left: Frontispiece portrait in coloured chalk by William Strang (1903), described on p. xi. Right: From the painting by Wayman Adams (1917), shortly after Pennell's return to America (p. 355).

Joseph Pennell, celebrated member of the Royal Society of Painter-Etchers and Engravers, and biographer of Whistler, was well known for his acrid remarks of a bitter and critical nature — remarks that the Royal Society's journal, with its disinclination to offend or hurt the feelings of any living member, finds it difficult to emulate. In his book Etchers and Etching (1920), he observed: "The person who does not print his own plates or cannot is not an etcher, but a shop-keeper and a manufacturer, a lazy, incompetent loafer."

The fierceness of this quotation may surprise many, especially when emphasised by the linear surround added on its original appearance, by the printer who evidently felt as strongly as Pennell on this point. As shown in his books, Pennell was a peppery individual; and yet his indignation and often outright fury with those who conduct our world so often into the chaos of destruction was perhaps not without some provocation. He was an idealistic man who could not bear not to comment upon the inept, the incompetent and the would-be expert who hides his failings beneath a glaze of seeming superiority. He cannot have been too popular, as he so often put his thoughts into print. Nonetheless, we can admire his courage, and the words do tend to lift from the page, and what greater value can they have when so many others of the same date form pages immobilised by time, and paralysed into their period.

We have tried to select passages from his Etchers and Etchings (1920) and his Adventures of an Illustrator (1925) that show not only something of himself but his often discerning (and disconcerting) views of his contemporaries and the etchers of past history. Pennell's views are often governed by prejudice of a fierce kind, sometimes his own, sometimes that of his era; but at least they are opinions, and we do not have to accept them after all. There is much to be learnt from Pennell, as he was a working etcher and draughtsman of immense experience, working every day, and knowing his art and craft totally.

Pennell's Views on Etching in 1881

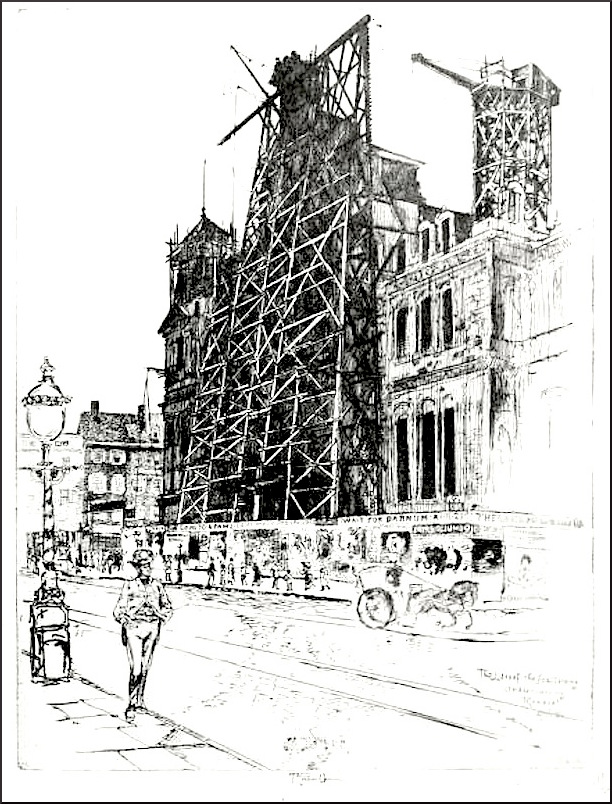

Two early works: Left: Dating from 17 July 1873, this is a drawing of a house on Fisher's Lane, opposite the Pennells' home: it won a prize at Germantown school. Pennell captioned it proudly, "Drawn in Pencil from Nature" (p. 27). Right: "Erection of the City Hall, Philadelphia. Etching made 1881. The Plate won me election to the Royal Society of Painter Etchers London" (p. 75).

Pennell's views on illustration are trenchant: "My work was finished on the spot, all done from nature. This is the right way to illustrate. I have always worked this way when possible and not copied sketches. To copy photographs is death to an artist, though the chain anchor of incompetents and commercials," he wrote (66). Writing about America in 1881,he mentioned the then popular Etching Clubs: "Every town then, as now, had an Etching Club, but ours [Philadelphia] and the New York one were real clubs. We met once a month at someone's studio, but in the meantime we each etched a plate and pulled enough proofs to exchange with the other members over beer and pretzels, or champagne and chicken salad, at the members' houses" (77).

Pennell on Etching in Florence in 1883

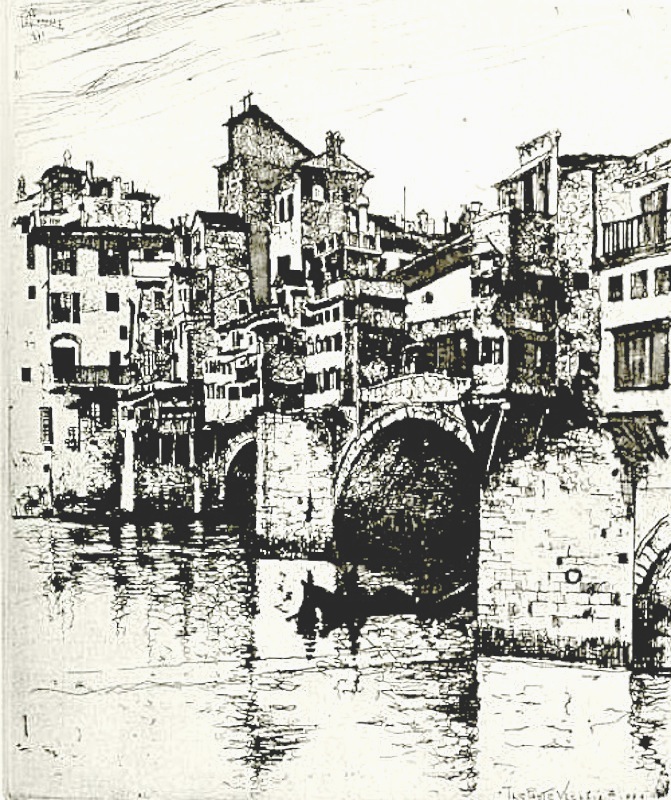

"The Ponte Vecchio, Florence. The fist etching made in Europe" (p. 103).

Pennell's views on illustration are trenchant. From The Adventures of an Illustrator, here is a somewhat terrifying account of Pennell etching on the spot. It would seem he had not got his technique as organised as has Norman Ackroyd (b. 1938) today:

I went to Italy to make my etchings and they were what I cared for. All day and every day I worked at them, drawing them straight on the plates, and that is why they and other proofs by etchers who draw from nature on the copper are reversed in printing. I even tried to bite them out of doors as I drew them — Hamerton had recommended that — but only once, for I could not see and I swallowed the fumes of acid as I bent over the flat easel which held the bath, and then I upset that. One experiment was enough, but the crowd enjoyed it, especially when the fumes ate the skin off my throat and I spat blood all about, and they wanted to send for the Misericordia brothers and take me to a hospital, but by that time so great a crowd had gathered that the police came out and drove us all away. The poor artist always draws a crowd he dont [sic] want, the poor pedlar rarely gets the crowd he longs for, and the police move us both on. But sometimes the artist turns. Whistler would threaten to stab the nearest with a needle. I could spatter them with ink as I pretended to clean my dirty clogged up pen. [108]

Later, he wrote: "I shall never forget the fury of Stillman, the critic and correspondent, mad on photography, when he found me perched on the parapet of the Lung Arno, and offered to photograph the subject for me so that I could do it more exactly, and I spurned his offer." He went on to say that he himself "was so pleased with some of my prints pulled on an old wooden press in an old shop behind the Uffizzi that I sent them to Ruskin, who kept or destroyed them, and never answered my gushing letter; besides, he was too much interested in Miss Alexander, and her stories and drawings of Florence, to bother about me" (117-18). Nevertheless, on the strength of the dozen or so etchings done in and around Florence, wood-engravings of which appeared in The Century," he explains, "I was made a Fellow of the Royal Society of Printer-Etchers, and taken like Whistler in his early days, quite seriously in England" (118-19).

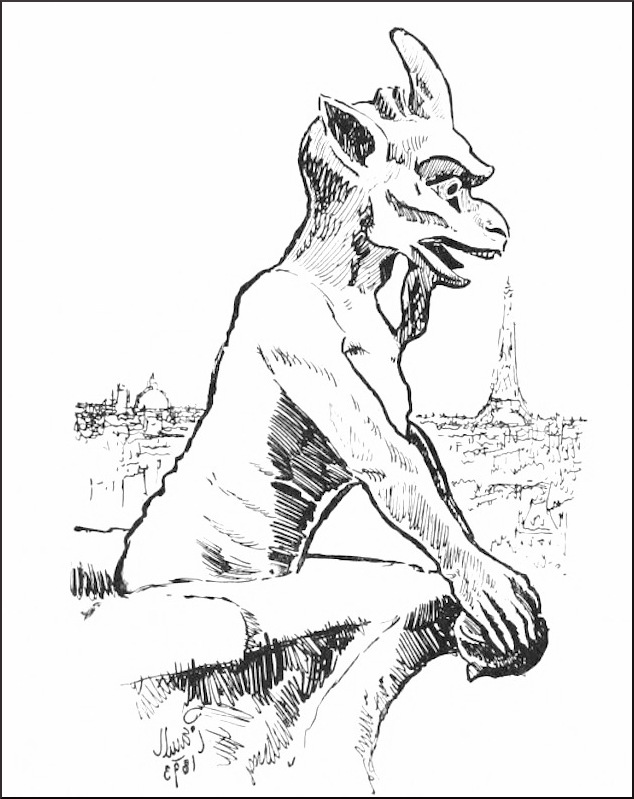

Pennell at Notre Dame in Paris in 1889

The "devils" of Notre Dame. Left: Pennell's "Pen Drawing Printed in the Pall Mall Gazette..." (p.212). Right: A similar chimera in a modern photograph by Siren-Com (Wikimedia Commons).

Now here is Pennell listening to the caretaker on the top of Notre Dame, who probably talked to the artist all the time he was drawing, as people do:

The Minister of Fine Arts gave me permission to use one of the towers as a studio and day after day I toiled up and drew a devil and heard his story from the Old Guardian, a relic of 1870. The devil was only a copy; Viollet-le-Duc saw to that. The Guardian told me ... stories of the suicides till the wire nets were put up below the balcony around the towers; of the man who threw himself over and repented as he fell and grabbed a gargoyle, slowly slipping till his last finger gave way; and of the woman who rushed up and jumped over and was caught by her skirts, which tore as she struggled; and of those who jumped clear and bounded up in the air when they hit the pavement; and how they would all rush out of the door of the stairs and hurl themselves over when he was not looking. I wonder if he told these stories to Victor Hugo? [203-04]

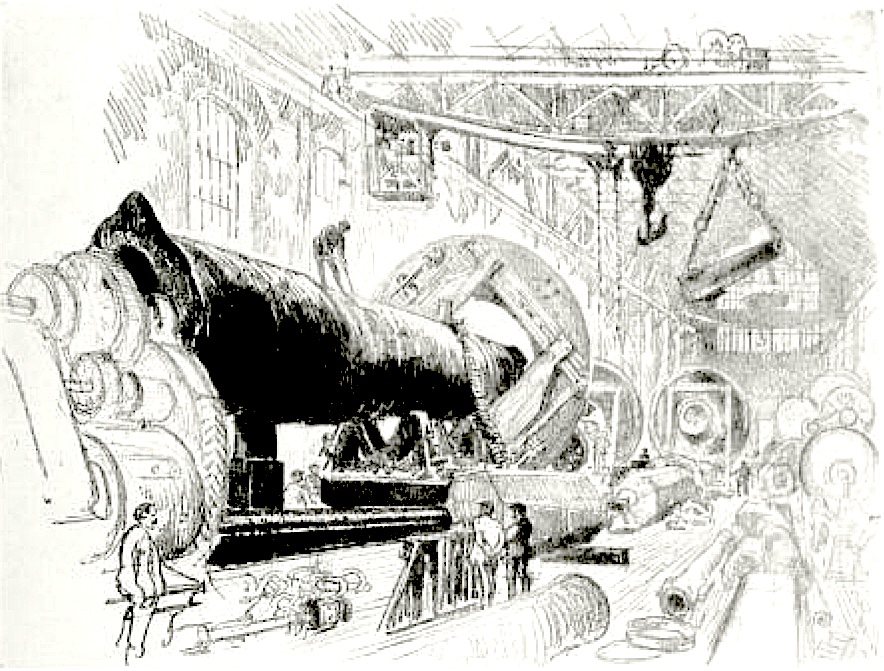

Pennell in 1916, in War-Time Britain

An example of Pennell's war-work: "Turning the Big Gun, Vickers-Maxim, Sheffield. Lithograph, 1916" (p.335).

Finally, here is Pennell working as a war artist in World War One and drawing a munitions factory in Leeds:

One day as I worked, a crowd gathered in the distance and I knew there would be trouble. Then a policeman appeared, and I showed him my pass.... he said I must go along with him to his Inspector.... Off we went. The crowd grew, for work was over and the pubs were full. He suggested that we get on a car, though he said the police station was only a few hundred yards away. I replied we would walk. The crowd grew, mostly behind us, and so I asked him to get behind me, for we were in that part of England where the natives "'eave 'arf a brick at the furiner," and the foreigner is anyone they do not know. No bricks came, but the crowd grew, mostly women. They drew closer, they shouted louder, and then someone yelled, "German spy!" and the rest took it up, and if the station had not been near, I do not think I should have reached it, for the street was solid with women, everyone shrieking, and the Bobby quite unarmed. I certainly did not like it. We went into the police office and the door was locked; but the crowd blocked the iron-barred windows to see the spy. When I showed my papers, they were found in order. But the crowd was not. There were three policemen inside and at least three hundred people in front of the station. The Inspector offered to get a cab and send me to the hotel – a horse cab. I thanked him and said I had no intention of forming the head of a procession which might drag me where they wanted or hang me by the traces to a lamp-post. But the Inspector was a man of brains. A trolley line passed the station and he stopped a car and held it up for five minutes till the track was clear. Then he and the three officers found truncheons and sallied out with me in their midst. What a yell went up. What a rush was made. But we jumped on the car, and, when the crowd tried to get aboard, they had their fingers rapped and fell off. The car started full speed, leaving the crowd in a minute, and it kept on for a mile, despite the protests of the passengers who were shot past their stopping places. Then we slowed down and stopped, the passengers got off, the police got off, and I returned quietly to the hotel by which the car passed. In that half hour I learned how it must feel to be a condemned murderer or a captured spy. The mere fact that a spy would never carry a big sketch block, a big bag of chalks and tools, and a sketching stool only convinced the people that I was a spy. [332-34]

Pennell concludes with a question to which he gives an interesting answer: "Why does war make people so idiotic, why do people fear an artist more than an enemy. Art is powerful and the people hate it. They feel it is above them and they hate it all the worse" (334).

Bibliography]

Pennell, Joseph. The Adventures of an Illustrator, Mostly in Following His Authors in America & Europe. Boston, Mass.: Little, Brown and Company, 1925. Internet Archive. Contributed by the University of Pittsburgh Library System. Web. 6 January 2015.

Last modified 15 November 2015