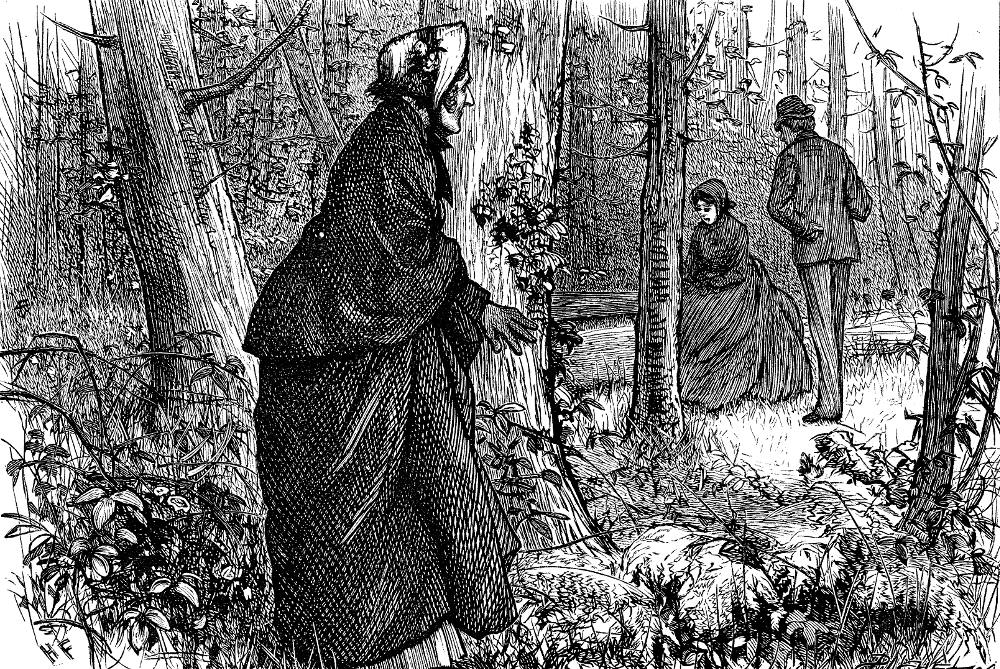

Mrs. Sparsit Saw with Delight That His Arm Embraced Her by Charles S. Reinhart. 13.2 cm wide by 10.2 cm high. This plate illustrates Book Two, "Reaping," Chapter Eleven, "Lower and Lower," in Charles Dickens's Hard Times in Charles Dickens's Hard Times (American Household Edition, 1876), 196; running head: "Mrs. Sparsit's Triumph," 197.

Passage Illustrated

Bending low among the dewy grass, Mrs. Sparsit advanced closer to them. She drew herself up, and stood behind a tree, like Robinson Crusoe in his ambuscade against the savages; so near to them that at a spring, and that no great one, she could have touched them both. He was there secretly, and had not shown himself at the house. He had come on horseback, and must have passed through the neighbouring fields; for his horse was tied to the meadow side of the fence, within a few paces.

"My dearest love," said he, "what could I do? Knowing you were alone, was it possible that I could stay away?"

"You may hang your head, to make yourself the more attractive; I don’t know what they see in you when you hold it up," thought Mrs. Sparsit; "but you little think, my dearest love, whose eyes are on you!"

That she hung her head, was certain. She urged him to go away, she commanded him to go away; but she neither turned her face to him, nor raised it. Yet it was remarkable that she sat as still as ever the amiable woman in ambuscade had seen her sit, at any period in her life. Her hands rested in one another, like the hands of a statue; and even her manner of speaking was not hurried.

"My dear child," said Harthouse; Mrs. Sparsit saw with delight that his arm embraced her; ‘will you not bear with my society for a little while?"

"Not here." [Book Two, "Reaping," Chapter Eleven, "Lower and Lower," 196-97]

Commentary

With her claw-like hand gripping the tree-trunk as she peers around it to spy on James Hartohouse's assignation with Louisa Bounderby, Mrs. Sparsit seems to repeat the actions of the witches in fairytales such as "Hansel and Gretel." Here, Dickens narrates the accompanying text not with fairy-tale omniscient narrator, but from Mrs. Sparsit's perspective, so that we experience her elation and self-congratulation. Dickens ironically terms Mrs. Sparsit "the amiable woman in ambuscade" (197). But in her moment of apparent triumph (as proclaimed by the running head "Mrs. Sparsit's Triumph," 197), rain begins to fall, preparing us for a thoroughly rain-soaked witch, who will shortly be stripped of her powers over Bounderby. She will proclaim Louisa an adulteress, only to learn that Mrs. Bounderby has returned to her father rather than run off with Harthouse.

Since the moment illustrated occurs just under — and therefore after — the illustration, the reader encounters the wood-engraving, then waits with anticipation (much like the malignant observer) to encounter the moment of Mrs. Sparsit's "delight" when she revels at having caught the pair as lovers. As in the text, she has crept forward through the gloom of the woods on Bounderby's estate. She feels thrilled to be the agent of propriety, of morality, of civilisation; she sees her function as being like that of Robinson Crusoe when he watches the cannibals land on the island in Defoe's best-selling eighteenth-century novel.

In the Reinhart illustration, Mrs. Sparsit has drawn herself up behind a tree. Whereas in the accompanying text the couple are sitting "by the felled tree" with Harthouse's mount "tied to the meadow side of the fence, within a few paces" (196), Reinhart only suggests the horse only by Harthouse's riding habit and the open meadow by the light behind the couple, who are seated on a convenient bench of the illustrator's own invention. The "savage" here, ironically, would seem to be the witch-like Mrs. Sparsit rather the fashionably acoutered lovers. Dickens's so designating Harthouse and Louisa may be a comment upon how Mrs. Sparsit regards their discarding social convention (Louisa's being married, and meeting in private with an admirer) and giving in to their sexual instincts. Reinhart's arranging the composition as he has done compels us to regard the lovers from Mrs. Sparsit's perspective, as in the text, and to reflect upon what use she intends to make of her knowledge of the affair, as yet in its incipient stages — and never to be consummated.

Harry French's Version of This Same Scene (1877)

Right: The British Household Edition's version of the same scene,

foregrounding the patient observer:

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Dickens, Charles. Hard Times for These Times. Illustrated by C. S. Reinhart. The Household Edition. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1876.

_______. Hard Times for These Times. Illustrated by Harry French. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1877.

Houfe, Simon. The Dictionary of Nineteenth-Century British Book Illustrators and Caricaturists. Woodbridge, Suffolk: Antique Collectors' Club, 1978.

Pennell, Joseph. The Adventures of An Illustrator Mostly in Following His Authors in America and Europe. Boston: Little, Brown & Co., 1925.

Created 22 October 2002

Last modified 7 August 2020