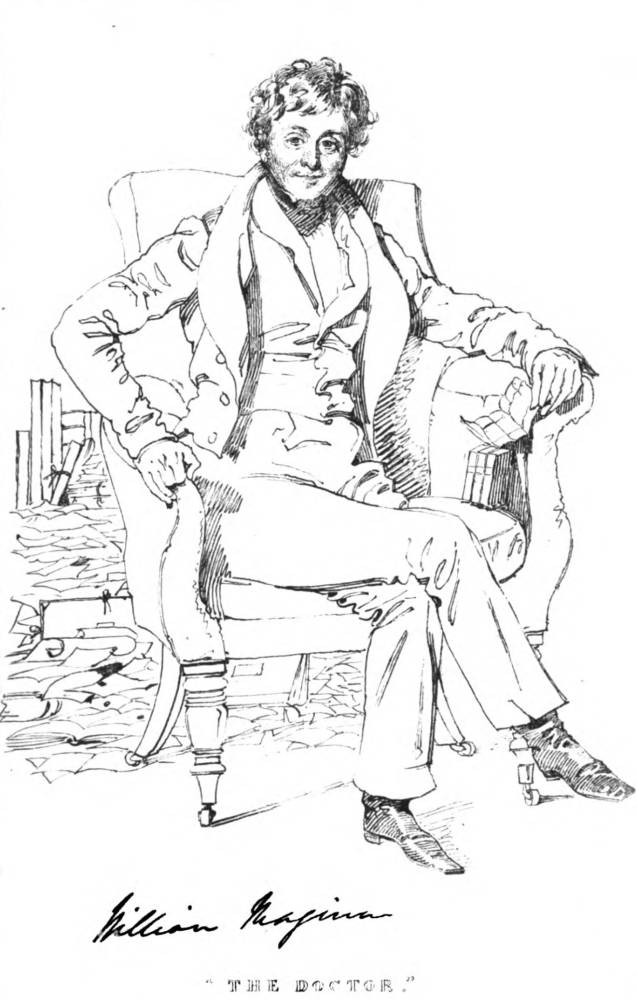

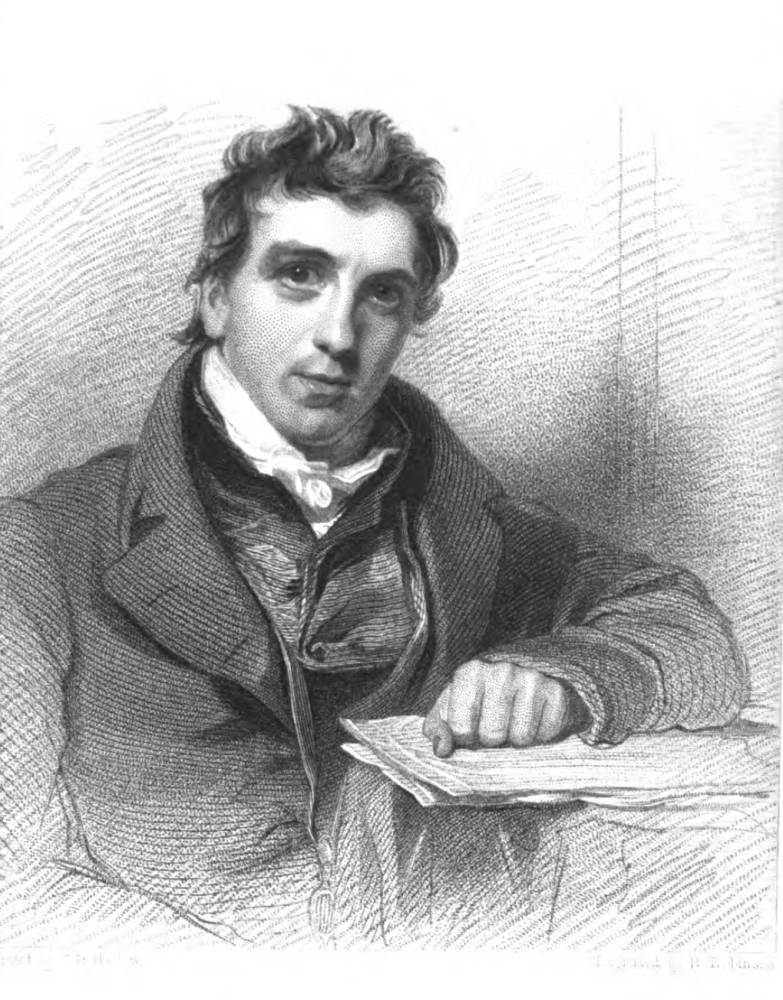

Left: Letitia E. Landon. Middle left: John Forster. Middle right: William Maginn. Right: William Jerdan . [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Landon almost married John Forster, editor of The Examiner, later biographer of Charles Dickens and Walter Savage Landor. He was ten years younger than Landon and somewhat of a social climber. L.E.L. was the perfect wife to complement his ambitions, and they eventually became engaged. Jerdan liked Forster and it is impossible to know what his feelings were upon hearing this news. The engagement triggered a revival of the old scandals. Landon’s name was linked with Jerdan and also, as before, with William Maginn, Daniel Maclise and Edward Bulwer-Lytton. There was further scandal concerning letters from Landon. Maginn’s biographer explained what had happened:

Finally, it is said, Mr Forster received in a blank envelope, several letters written by L.E.L. addressed to Dr Maginn, familiarly commencing with the words ‘My dearest William’ and written in a tone of affectionate friendship which the quick jealousy of a lover interpreted as confirming the worst report which anonymous slander had breathed into his mind…in a paroxysm of rage and suspicion Mr Forster enclosed the letter to L.E.L., with one line saying that they were ‘parted for ever’, that the love-epistles which he had sent back explained why. [Mackenzie 5.lxxxv]

Forster had been sent these letters by Maginn’s wife in a fit of pique when she discovered them in her husband’s desk. She confessed her action to Forster and believed that she had wronged Landon, but by then it was too late to remedy the situation.

Michael Sadleir, Bulwer-Lytton’s biographer, suggests another explanation: Maginn wrote several anonymous letters to Landon’s friends, accusing her of being the mistress of a married man (423). She was, of course, but Jerdan was not the married man rumour lit upon, but Maginn himself who, in the 1830s, was living contentedly with his wife. Maginn had a history of baiting Bulwer in Fraser's, and in the Age, quite probably with the connivance of Westmacott. His hatred of Bulwer may have arisen from his perception that Landon had rejected his own advances, whilst being intimate with Bulwer and his wife, and the anonymous letters were his revenge upon her.

Maginn was widely considered brilliant but fatally flawed in his love of drink and women. Certainly, Samuel Carter Hall clearly despised him, saying that “A man less likely to have gained the affections of any woman could not easily have been found. To say nothing of his being a married man – dirty in his dress and habits, revolting in manners, and rarely sober, he might have been pointed out as one from whom a woman of refinement would have turned with loathing rather than have approached with love” (278). In further vindication of Landon’s behaviour, Hall published her letter to his wife, vehemently attacking Mrs Maginn as spiteful for accusing Landon of having written twenty-four love letters to Maclise, and of “sheer envy, operating upon a weak, vulgar, but cunning nature” (277). Landon utterly denied any wrongdoing with Maginn, claiming to have been so afraid of him that she had to force herself to be civil.

When the rumours reached the ears of Forster, he asked Landon to refute the stories. She told him to ask her friends for their opinion. He did so, and was satisfied as to her innocence, at which point Landon broke off their engagement. Her friend Laman Blanchard later printed her letter to Forster in which she said she could not allow him to marry a woman whose honour had been called into question – it would not be fair to him. Blanchard approved of this sentiment, calling it “the self-sacrifice she deemed herself called on by duty to make” (129). This was the reason that was allowed to circulate as to why the engagement was at an end. However, privately Landon wrote to her good friend Bulwer Lytton in a very different tone: “If his future protection is to harass and humiliate me as much as his present – God keep me from it – I cannot get over the entire want of delicacy to me which could repeat such slander to myself. The whole of his late conduct to me personally has left behind almost dislike – certainly fear of his imperious and overbearing temper. I am sure we could never be happy together” (Sadleir 426).

This tone of self-righteous indignation would be amusing, given the known facts of her affair, were it not yet another of Landon’s masks, hiding the truth, maybe even from herself. From a perspective of time it seems rather odd that she broke her engagement to a highly respectable, suitable man whom she must at least have liked initially, thus necessitating continuing the hard-working, fairly Spartan life she was leading. However, taking the measure of the man and her times, she could never have divulged to him the existence of her children, having once convinced him of her innocence and purity. If the truth became known and she was one day exposed as their mother, it would have created a situation untenable both for her and for Forster.

Katherine Thomson remembered that following the break-up of the engagement Landon became “morbid, desperate, hopeless…Happily, her friend, her first friend Mr Jerdan and his daughters, did not forsake her on account of the coarse and cruel manner in which the name of L.E.L. had been traduced on his account. They were devoted to her to the last” (298). Was Thomson really as hoodwinked as she appeared to be, or was the passing reference to Jerdan’s daughters a way of hiding what she knew of the illicit relationship behind a cloak of respectability?

In this year Landon wrote a short story called “The Head”, which highlighted the unwritten rules of fashionable society where it was tacitly accepted that a married woman may have lovers without the slightest intention of giving up her wealth and position to run away with them. The frustrated lover in Landon’s story groans “Curse on these social laws! Which are made for the convenience of the few and the degradation of the many” (Lawford 325). That was the crucial difference which bedevilled Landon: she was not a married woman, but a single, independent, professional woman, for whom it was unthinkable to take even one lover, let alone more.

Bibliography

Blanchard, Laman. The Life and Literary Remains of L.E.L. London: Henry Colburn, 1841.

Cross, Nigel. The Royal Literary Fund 1790-1918. London: World Microfilms, 1984.

Disraeli, R. Ed. Lord Beaconsfield’s Letters 1830-1852. London: John Murray, 1887.

Griffin, D. Life of Gerald Griffin. London: 1843.

Hall, S. C.Retrospect of a Long Life. 2 vols. London: Richard Bentley & Son, 1883.

Hall, S. C. The Book of Memories of Great Men and Women of the Age, from personal acquaintance. 2nd ed. London: Virtue & Co. 1877.

Jerdan, William. Autobiography. 4 vols. London: Arthur Hall, Virtue & Co., 1852-53.

The Letters of Letitia Elizabeth Landon. Ed. F. J. Sypher, Delmar, New York: Scholars’ Facsimiles & Reprints, 2001.

Landon, L. E. Romance and Reality. London: Richard Bentley, 1848.

Landon, L. E. Letitia Elizabeth Landon: Selected Writings. Ed. Jerome J. McGann and D. Reiss. Broadview Literary Texts, 1997.

Lawford, Cynthia. “Diary.” London Review of Books. 22 (21 September 2000).

Lawford, Cynthia. “Turbans, Tea and Talk of Books: The Literary Parties of Elizabeth Spence and Elizabeth Benger.” CW3 Journal. Corvey Women Writers Issue No. 1, 2004.

Lawford, Cynthia. “The early life and London worlds of Letitia Elizabeth Landon., a poet performing in an age of sentiment and display.” Ph.D. dissertation, New York: City University, 2001.

Macready, William Charles. The Diaries of 1833-1851 Ed. W. Toynbee. 2 vols. London: Chapman & Hall, 1912.

Marchand, L. The Athenaeum – A Mirror of Victorian Culture. University of North Carolina Press, 1941.

Mackenzie, R. S. Miscellaneous Writings of the late Dr. Maginn. Reprinted Redfield N. Y. 1855-57.

McGann, J. and D. Reiss. Letitia Elizabeth Landon: Selected Writings. Broadview Literary Texts, 1997.

Pyle, Gerald. “The Literary Gazette under William Jerdan.” Ph. D. dissertation, Duke University, 1976.

Sadleir, Michael. Blessington D’Orsay: a Masquerade. London: Constable, 1933.

Sadleir, Michael. Bulwer and his Wife: A Panorama 1803-1836. London: Constable & Co. 1931.

Sypher, F. J. Letitia Elizabeth Landon, A Biography. Ann Arbor, Michigan: Scholars’ Facsimiles & Reprints, 2004, 2nd ed. 2009.

Thomson, Katharine. Recollections of Literary Characters and Celebrated Places. 2 vols. New York: Scribner, 1874. Reprinted Kessinger Publishing.

Thrall, Miriam. Rebellious Fraser’s: Nol Yorke’s Magazine in the days of Maginn, Carlyle and Thackeray. New York: Columbia University Press, 1934.

Vizetelly, Henry. Glances back through seventy years. Kegan Paul, 1893.

Last modified 16 July 2020