On Wednesday, 26 September 1883, the following letter was published in The Times announcing an Osborne Gordon Memorial:

Sir, – The committee appointed to promote a memorial to the late Osborne Gordon have to request that you, with your usual courtesy, will allow them to make known, through The Times to any of Mr. Gordon's friends who have received no direct intimation of the proposed memorial, that if they should wish to take part in it they should communicate with one of the secretaries on the subject before October 10.

Subscriptions (not to exceed £2.2s) can be paid to either of the secretaries, or to the Osborne Gordon Memorial Fund, Messrs. Parsons and Co., Old Bank, Oxford.

A general meeting of subscribers (at present about 120 in number) will be held in the course of the October term, at Christ Church, to determine the form of the memorial.

On behalf of the committee, we have the honour to be, Sir, your obedient servants,

Geo. Marshall

R.Godfrey Faussett Hon. Secs.

Christ Church, Oxford, Sept. 19.

The public responded generously and support, in addition to that of Marshall and Faussett, was given by John Ruskin and many other public figures – the Lord Bishop of Oxford, the Lord Bishop of Manchester (Fraser, Gordon's old school friend), the very Rev. the Dean of Winchester (Gladstone had appointed George William Kitchin to the deanery of Winchester in April 1883), the Archdeacons of Berkshire and Maidstone, the Rt. Hon. Sir John Robert Mowbray (1815-1899) MP for Oxford University, the Rt. Hon. Sir Michael Hicks-Beach, Sir R. Harington, Col. H. B. N. Lane, John Gilbert Talbot MP for Oxford University, H. W. Fisher, the Rev. Canon Hill, Thomas Vere Bayne (1829-1908), H. L.Thompson, the Rev. E. F. Sampson (Tutor at Christ Church), the Rev. Richard St John Tyrwhitt (1827-1895) (writer on art, illustrator of the mountain murals in the Oxford Museum and friend of Ruskin). The Dean and Chapter of Christ Church wholeheartedly endorsed the proposal and ensured its successful completion.

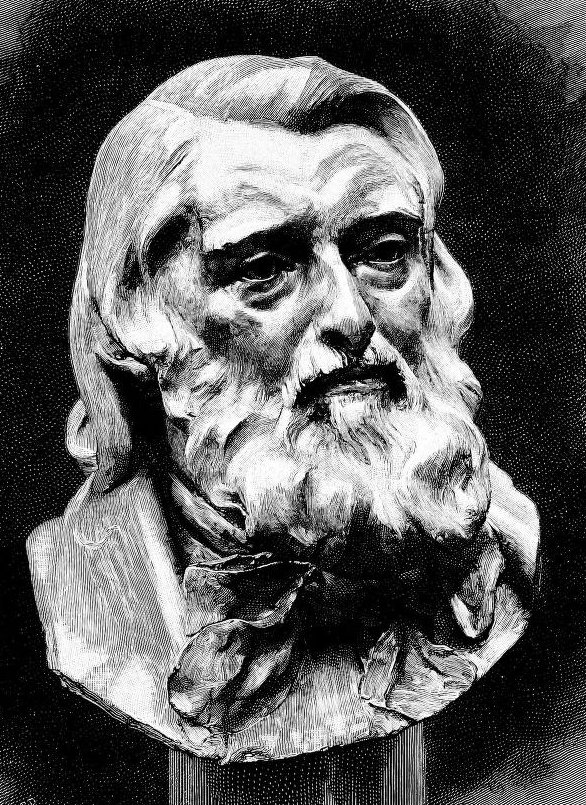

John Ruskin by Conrad Dressler. 1889. Source: Spielmann 171.

The two bournes of Gordon's life were Christ Church and Easthampstead. It is appropriate that these places were chosen for his memorials. It was decided to commission a bust of Gordon and an inscription in Latin next to it to be placed in the Cathedral cloister of Christ Church. The work was executed by Conrad Dressler (1856-1940), an English sculptor of German descent who had studied at the Royal College of Art with Joseph Edgar Boehm (1834-1890). Boehm's bust of Ruskin had been placed in the Drawing School in Oxford in 1881. Dressler had acquired a reputation for large, portrait-medallions in bronze – of Sir John Mowbray and Henry Morton Stanley (1841-1904), the explorer. He was also a friend of Ruskin who may have suggested him as a suitable sculptor for Gordon's bust. In the spring of 1884, Dressler was a frequent visitor to Brantwood for a series of sittings that took place in an out-house where Ruskin, seated upon a platform, posed. A bust of the bearded Professor was completed later that year (Spielman 180-85).

Dressler explains in a long letter of 18 June 1890, to the art critic and biographer of Ruskin, M. H. Spielmann, how he first made the acquaintance of John Ruskin and when Ruskin first saw the memorial bust of Gordon:

It was in the summer of 1883 that I first made the acquaintance of Professor Ruskin. He came to Chelsea to see the memorial of Mr Osborne Gordon which I was then modelling for Christ Church, Oxford. He remained looking at things and chatting for an hour or two, and as he left, he invited me to his country house. I was only able to go in the following spring. [Quoted Dearden, Ruskin: A Life in Portraits, from a letter in the Pierpont Morgan Library PML 54632]

In Memoriam: Easthampstead

Left: The Church of St Michael and St Mary Magdalene, Easthampstead. Right: Tomb of the Rev. Osborne Gordon in the churchyard of St Michael and St Mary Magdalene. Both photographs 2007 by the author.

In his old parish church at Easthampstead, Gordon’s memory was perpetuated and honoured by the skills of some of the greatest figures in Victorian England. Of these, three were also Oxonians, who had actively engaged with Gordon in so many different ways during his lifetime: Edward Burne-Jones, William Morris and John Ruskin. A window, a pavement and a tablet were erected. These memorials inside the church would have been initiated and approved by Gordon’s immediate successor, the Rev. Herbert Salwey, and no doubt by the Christ Church authorities. Herbert Salwey (1842/3-1929) was the sixth son of the Rev. Thomas Salwey (1791-1877), vicar of St Oswald’s Church, Oswestry, in north Shropshire, near the Welsh border, from 1823 to 1871. Thomas Salwey, from a very old Shropshire family, the Salweys of Orleton near Ludlow, was an outstanding field naturalist, famous in particular as a Mycologist and a Lichenologist. Herbert Salwey had a keen sense of the importance of history and physical memorials, for, along with his siblings, he had dedicated a fine stained-glass window to the memory of their father in Oswestry parish church. So it is perhaps not surprising that he devoted considerable energy and time to ensuring the memory of Osborne Gordon by some of the finest craftsmen of the age.

Memorial Window

Left: The Magi. Middle: The Nativity. Right: The position of the memorial windows in the church. Photos by the kind permission of the Rev. Guy Cole.

A two-light stained glass memorial window, the collaborative work of Burne-Jones and Morris & Co, was placed at the east end of the north side of the chancel in 1885, depicting The Adoration of the Magi. In the left panel of this memorial to Gordon, three Magi, one clad in white, another in yellow and the third in deep blue, with gifts in their hands, look in the direction of the right-hand panel which depicts the nativity scene – Joseph, dressed in dark red, Mary, in luminous blue, and four red-winged figures in white robes paying homage to the Christ child.

Mosaic

Craftsmen from the firm of Farmer and Brindley, sculptors of 67 Westminster Bridge Road, London [William Farmer (1823-1885) and William Brindley (1832/3-1919)], who had worked on the University Museum in Oxford, were charged with "executing and laying [a mosaic] floor" just inside the high altar rails and forming the footpace (raised portion of the floor) and floor to the sanctuary. Farmer and Brindley charged £151.

The mosaic pavement was designed and supervised by Thomas Graham Jackson (1835-1924), at a cost of £15.15s, and completed by May 1885. Jackson was a prolific architect and writer on art and architecture who had, in the words of Pevsner in his Penguin Oxfordshire "set his elephantine feet on many places in Oxford". Jackson shot to fame after winning the competition for the design of the New Examination Rooms, and thereafter changed the face of Oxford as he gained more and more contracts for University work (Hertford College, Brasenose).

Two views of Thomas Jackson’s work at Brasenose College, Oxford. Left: The New Quad. Right: Looking past the chapel from the Deer Garden into the New Quad.

In one of his lectures on art, "The Fireside: John Leech and John Tenniel", delivered during his second tenure as Slade Professor at Oxford on 7 November – and repeated on 10 November – 1883, Ruskin inveighed against Jackson's overuse of Renaissance features, with particular reference to the New Examination Rooms in the High Street, built 1876-1882 (ironically later housing The Ruskin School of Art!). Ruskin angrily declaimed to his packed audience:

It is a somewhat characteristic fact, expressive of the tendencies of this age, that Oxford thinks nothing of spending £150,000 for the elevation and ornature, in a style as inherently corrupt as it is un-English, of the rooms for the torture and shame of her scholars […]; but that the only place where her art-workmen can be taught to draw, is the cellar of her old Taylor buildings, and the only place where her art professor can store the cast of a statue, is his own private office in the gallery above. [30.363]

Such was Ruskin's disdain that he refused to enter the building when Jackson's assistant, William Marshall, invited him! (Jackson 120)

The plaque containing Ruskin’s words dedicating the mosaic floor to Gordon’s memory and the floor itself. Photos by the author.

It is ironic that the work of a man whose aesthetic principles Ruskin abhorred, at least in architecture, should find a place next to Ruskin's own homage to Gordon at Easthampstead. However, although Ruskin did not, to our knowledge, see Jackson's mosaic, the results would surely have pleased him. The mosaic is a stunning creation using the best quality materials and best quality workmanship (that was the ethos that Gordon had always fostered in his embellishment and maintenance of his church). The lower floor is overlaid with slabs of green Serpentine marble, veined with white, and interspersed with three red Porphyry roundels. The dais has a border of mottled amber Verona Rosso marble which frames wavy, flowing, tessellated shapes. There is much interweaving, intertwining and fillet braiding in a natural manner. One sees stylised ivy leaves and geometric inlays inspired by Italian Cosmati mosaic work, named after the family of that name, famous as skilled architects and for their decorative geometric mosaics, especially for church floors.

Ruskin wrote extensively about mosaics, especially those he had seen in Venice, and about different kinds of marble and its use in architecture. In his first published major work on architecture, The Seven Lamps of Architecture (complete text), Ruskin was attracted by the patterns and the highly abstract use of mosaics often introducing brilliant colours, with examples from Torcello, Parma, Lucca, Verona and Venice. The design of the cover of the first edition of The Seven Lamps of Architecture, with its graceful adaptation of connecting arabesques, was inspired by the mosaic of the floor of the nave of the church of San Miniato al Monte in Florence (8.185). Ruskin’s seven Lamps of Sacrifice, Truth, Power, Beauty, Life, Memory and Obedience are rendered into Latin, on the cover of the first edition, as Religio, Fides, Auctoritas, Observantia, Spiritus, Memoria and Obedientia. Each is boldly placed within a roundel interlinking with the tracery and designs of the whole. The "lamps" on the cover are placed among patterns of animals (a ram, two lions rampant and a mythological griffin) and birds (an eagle, three pairs of facing birds) and interlinking branch and leaf designs, as well as several small roundels. Several of these motifs can be found in the Zodiac pavement and in others parts of the floor mosaic at San Miniato al Monte. In The Stones of Venice a few years later, Ruskin devoted many pages to mosaics. He was interested in the range of colours such as the "harmony of purple with various green" and materials used. The "circular disks of green serpentine and porphyry" (these are the very stones used in the Easthampstead mosaic) were, he believed, "derived probably in the first instance from the suspension of shields upon the wall, as in the majesty of ancient Tyre" (10.170). James S. Dearden argues that George Hobbs, Ruskin’s assistant who worked in San Miniato for a considerable time in June 1846, copied the mosaics for Ruskin, making drawings or even tracings that were made available to Harry Rogers when he was designing the cover of The Seven Lamps of Architecture (Dearden, Facets of Ruskin 85-86).

In The Seven Lamps of Architecture, Ruskin analysed and categorised the characteristics of good Gothic, believing that architectural principles should mirror moral qualities. These guiding principles he called "lamps": for example, in the chapter entitled "The Lamp of Sacrifice", he formulated his belief that architecture should be an offering to God, the giving of the best work and the most expensive materials (a principle that can be seen in the church of St Michael and St Mary Magdalene at Easthampstead). The book is in praise of the Gothic stonemason who, Ruskin believed, worked with his heart and soul in the creation of beautiful living sculptures, demonstrating in particular the ethos of "The Lamp of Life".

Mosaics are beautiful but fragile. The warning that Ruskin gave in the mid-nineteenth century in a chapter in The Stones of Venice is relevant today, and especially in the context of the successful appeal to raise funds to restore the damaged Easthampstead mosaic: "Mosaic, while the most secure of all decorations if carefully watched and refastened when it loosens, may, if neglected and exposed to weather, in process of time disappear so as to leave no vestige of its existence" (10.170).

Jackson was steeped in Ruskin, and knew The Seven Lamps of Architecture and The Stones of Venice particularly well. As early as 1859, at the age of twenty-four, he noted in his diary:

I took to reading in the Art Library. Ruskin’s Seven Lamps of Architecture appealed to me so strongly that I made an analysis of it, and illustrated it with drawings of buildings it refers to, which I hunted up elsewhere. Ruskin does not teach one practical architecture, for which I might more usefully have looked elsewhere, but he puts a student into a properly reverential and receptive frame of mind and I am not sure that my choice, at this stage of my education, could have been better directed. The Stones of Venice, which I read next with avidity, fed the passion for Italy, and Italian Medieval art which had been fostered by a study of the Pre-Raphaelites. [Jackson 63-64]

Ruskin was hostile to Jackson's approach to architecture: the one and only encounter between the two strong men was nothing short of frosty. Although Ruskin was living a great deal in Oxford at the time (early 1880s), Jackson wrote in his diary:

I never made Ruskin's acquaintance, and indeed, saw him but once, when Miss Shaw-Lefevre [first Principal of Somerville, appointed on 3 May 1879] introduced me to him at Somerville Hall. He was standing on the hearthrug surrounded by a group of admiring girl-worshippers such as he liked, and with a shake of the hand our intercourse began and ended. He disliked my work, and called it debased, being a purist in styles, or rather in one style, Gothic. [Jackson 162]

Nevertheless, Jackson recommended Ruskin's major architectural studies as essential reading to his students, even in his later years:

I always advise my pupils to read, as I did, The Seven Lamps of Architecture and The Stones of Venice, though I am obliged to warn them that they will not learn architecture from Ruskin, as he considered architecture from a fallacious and unpractical stand-point; but it puts them into a receptive and reverential mental attitude and that, as I found in my own case, is the proper one in which to approach your art. [Jackson 162-63]

Epitaph

It was fitting that Professor Ruskin, one of Gordon's most prestigious, devoted surviving friends, should be asked to compose an epitaph. Here is a diplomatic transcription of Ruskin’s original manuscript:

The adjacent window and mosaic floor

This window

[are] Is dedicate to God’s praise

In loving memory of His servant

Beneath this tablet

is buried

Osborne Gordon

*Censor Student and *Tutor of Ch. Ch. Oxford

Rector of this Parish

From 1860 to 1883

An Englishman of the Olden Time

Humane, without weakness. Learned without ostentation

Witty without malice. Wise without pride

Honest of heart, Lofty of Thought

Dear to his fellowmen, and dutiful to his God

[He spent his pastoral life

In Kindly ministries, Errorless lessons

And Blameless example

Few lives so little conspicuous

Have been so largely useful as his

Few minds, as high in power

Like his, serene in activity, – undimmed in rest]

When his friends shall be also departed

And can no more cherish his memory

Be it yet revered by this stranger [Collins 64]

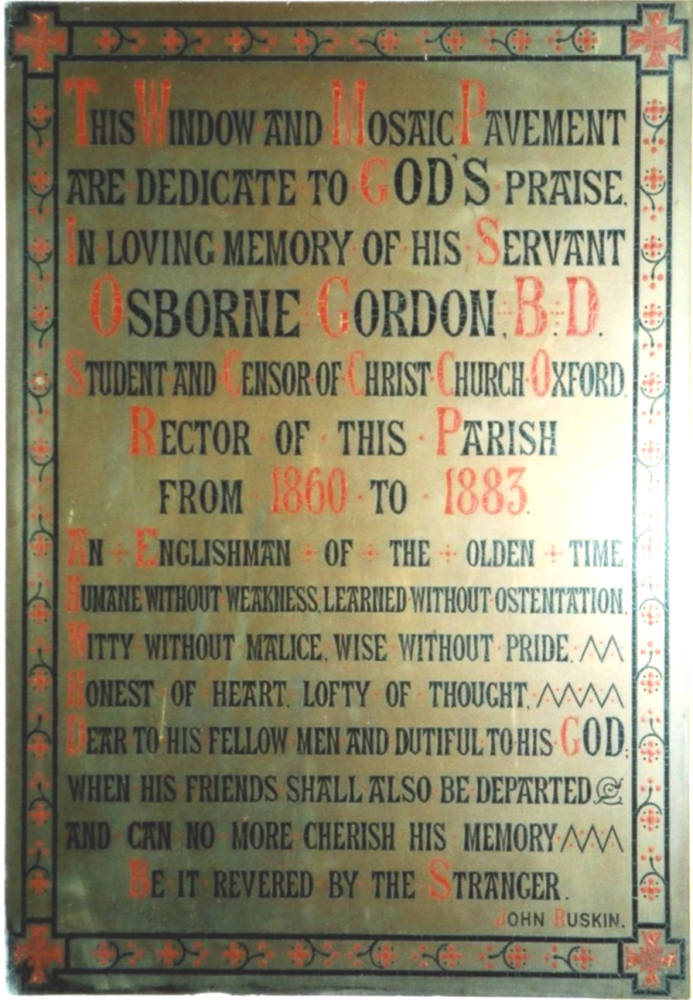

Ruskin’s draft was edited by the Rev. Herbert Salwey who considered it "verbose", and the following shortened version, signed John Ruskin, although not authorised by him, was inscribed on a brass plaque on the north wall of the chancel, to the left of the Magi and Nativity windows:

This Window and Mosaic Pavement

are dedicate to God's praise.

In loving memory of his Servant

Osborne Gordon, B.D.

Student and Censor of Christ Church Oxford,

Rector of this Parish

from 1860 to 1883.

An Englishman of the olden time,

Humane without weakness, learned without ostentation,

Witty without malice, wise without pride,

Honest of heart, lofty of thought,

Dear to his fellow men and dutiful to his God;

when his friends shall also be departed

and can no more cherish his memory

Be it revered by the Stranger.

John Ruskin.

The circumstances relating to this changed epitaph only became clear in October 1932 when they were explained in the following document prepared by Henry Julian White (1859-1934), Dean of Christ Church from 1920 until his death:

The Rev. T. W. W. T. Stubbs, Rector of Easthampstead, has lately received from Ruskin's former Secretary the original form of his famous Epitaph, and kindly sends me a copy.

The Rev. H. Salwey, who succeeded Osborne Gordon, cut out part of it as verbose, and sent the shortened form back to Ruskin for his sanction. Ruskin took no notice whatever of the letter, and Mr. Salwey had the shortened form placed in Easthampstead Church.

H. J. White.

Christ Church, Oxford,

October, 1932. [Ruskin, : Epitaph for Osborne Gordon, ref. 1996B0549, Lancaster].

The initials of Mr Stubbs have been amended by hand to W. T. in the typed document, representing accurately his names of Wilfrid Thomas. W. T. Stubbs was the son of William Stubbs, Bishop of Oxford from 1889 until his death in 1901.

"Ruskin's former Secretary" was Sara Anderson. Known as "Diddie", she had assisted Ruskin in the mid-1870s with the work of his Guild of St George. She became a very close friend of Joan Severn and gradually became part of the Ruskin family circle, helping Ruskin more and more with his correspondence and being party to intimate family affairs. Later, Sara also worked as the private secretary to Rudyard Kipling, and resided, along with a maid and a governess, in Park Mill Cottage, a house in the grounds of Batemans, Kipling’s Sussex home (Dawson 20-21).

Sara Anderson died in 1942, and Sydney Cockerell, Director of the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge from 1908 and with whom Sara had a close relationship, wrote of her qualities, particularly her discretion and loyalty to her employers, in his obituary notice of his friend in The Times of 30 November 1932:

Being on terms of intimacy with her employers, she [...] was possessed of many secrets which, however valuable as "copy", were very safe in her hands. Her lively understanding was happily lit up by a sense of humour, and she had an appreciation of their foibles, as well as of their genius, their strivings and their achievements. But after the great ones had departed, Sara Anderson never came into the open, never wrote down what she knew; never lectures or broadcast.

Ten years before her death, Sara Anderson made contact, unexpectedly, with the Rev. Wilfrid Thomas Stubbs, rector of the church of St Michael and St Mary Magdalene, Easthampstead from 1926 until 1938. Her first letter, written from 1 Earls Terrace, London W8, to the rector, dates from 23 August 1932, informing him that she possessed Ruskin's manuscript of the epitaph to Gordon and would like it to be hung "near the carved one". Mr Stubbs agreed to her request and to her offer "to have the Ms draft epitaph put in a suitable frame". Sara arranged for it to be put in "a simple gilt frame" and offered to bring it to the rector. Mr Stubbs invited her to lunch on the agreed day, Monday 12 September. However, she declined, explaining that "the afternoon trains are the most convenient & I shall aim at the 1.57 on Monday, which will take me to Bracknell at 3, & I daresay someone will tell me how to reach your Rectory" (letter of 8 September). As regards the final destination of the manuscript, she continued: "The Vestry will be a much better home for the MS than the Church, as it looks very un-clerical in a narrow gilt frame & no Chancellor of any Diocese could be expected to admit it to a church! I can but hope you will let it into your Vestry."

Sara Anderson’s Letters

I reproduce in full, and for the first time, by kind permission of Easthampstead PCC., three extant letters from Sara Anderson to the Rev. W. T. Stubbs about Ruskin's epitaph to Gordon.

Letter of 23 August 1932

23 August 1932

The Rector

Easthampstead

Dear Sir,

In my early life I was much connected with John Ruskin & I have several pieces of MS by him, among them the draft of the epitaph on the Rev. Osborne Gordon, once Rector of your Parish.

Ruskin is now little more than a name, but I have thought that it might be of some interest to have the MS draft epitaph put in a suitable frame (which I would have done for you) & hung near the carved one. The draft is written on a sheet of foolscap which, however, is not entirely covered, indeed the space occupied by the MS is only 9 x 8 ½ inches. […]

Letter of 4 September 1932

Dear Mr Stubbs,

I am so glad that you will give the MS epitaph a home.

I have taken it to a frame-maker, who is putting it in a simple gilt frame. It will be ready this week, & may I bring it down to you on Saturday the 10th, or preferably Monday the 12th?

Letter of 8 September 1932

Dear Mr Stubbs,

Thank you very much for offering me lunch, but I find, as you say, that the afternoon trains are the most convenient & I shall aim at the 1.57 on Monday, which will take me to Bracknell at 3, & I daresay someone will tell me how to reach your Rectory.

The Vestry will be a much better home for the MS than the church, as it looks very un-clerical in a narrow gilt frame & no Chancellor of any Diocese could be expected to admit it to a church! I can but hope you will let it into your vestry.

The opinion of the Dean of Christ Church, Henry Julian White, is interesting:

12 October 1932.

Dear Mr Stubbs,

Thank you for your most interesting letter. I had always regarded the Epitaph to Osborne Gordon as one of Ruskin’s finest compositions; and it is almost amusing to find that my old Censor Salwey had censored it to such good effect […]

In Memoriam: Gordon and Pritchard in Shropshire

In Shropshire, homages to the Pritchard-Gordon families can be found in Broseley, Jackfield, Much Wenlock and Bridgnorth. In Broseley Parish Church, there are tablets on the north transept wall in memory of John Pritchard Sr and son, and their families. One short inscription focuses on the son's status as a Member of Parliament:

To the Glory of God and in the memory of John Pritchard of Stanmore Hall, Bridgnorth for fifteen years one of the members of parliament Borough of Bridgnorth who died August 19th 1891 aged 94. Also of Jane his wife who died February 25th 1892, aged 75. Also of Mary Anne Pritchard, sister of above John Pritchard, who died March 5, 1882.

A substantial testimony to John Pritchard Sr's personal qualities and philanthropy is recorded on a nearby tablet:

In memory of John Pritchard solicitor and banker for nearly 50 years A resident in this parish He died the 15th June 1837 in the 78th year of his age. A kind and indulgent husband and father, A ready and faithful friend and adviser, A liberal benefactor of the poor, This good man so held his course as to gain the respect and affection of all around him, shewing by his example that the duties of an active profession, may be zealously discharge, without neglecting those essential to the character of a true Christian.

The surplus of a subscription for engraving the portrait of the deceased, enables his friends and neighbours, by this tablet, to perpetuate his memory.

The esteem in which George Pritchard, brother of John, was held is recorded in the inscription on his memorial, a marble tablet on the interior north wall in Broseley Church:

He trod in the steps of his honoured father and as a good neighbour, as a protector of the fatherless, and widow, as an able and upright magistrate, and as a considerate guardian and benefactor of the poor, he so entirely gained the affection and respect of all around him, that the church at Jackfield, and the monument in the public street of this place, were erected by public subscription to perpetuate his memory.

His domestic virtues and humble piety are best known to his widow and near relatives, who are left to mourn his loss, and who desire by this tablet to record their fond remembrance of one so justly loved.

A major problem in Broseley was the difficulty of not having access to supplies of water, even though the river Severn was close by. Records of 1811 state that water had to be carried, in winter, from a well, called the Down Well, about one and a half miles outside the town, and in summer, from distant brooks and from a pool called the Delph. The need for fresh and accessible water was urgent and was the subject of much debate, correspondence, and acrimony. It appears that George Pritchard agreed to finance a water supply from the property of Frederick Hartshorne, of Alison House, Church Street. A reservoir was constructed to store water fractured owing to mining subsistence. After George Pritchard's death, an ornate memorial fountain, designed by Robert Griffiths of Quatford, near Bridgnorth, was erected in the Square in Broseley in 1862. Built of Grinshill stone from quarries near Shrewsbury, it was octagonal in shape, with moulded, Gothic arches and ornamental gables, above which were appropriate inscriptions. The memorial looked like a little house; it was high and covered with a sloping roof surmounted by a tower and weather vane. The fountain, intended to provide water for the poor – but the high level of iron rendered it unusable – was demolished in 1947. Only the plinth remains.

In his will, George Pritchard left money to support the Jackfield curacy on condition that Jackfield, about three miles from Broseley, became a separate parish. A Memorandum dated 19 January 1859, found with George Pritchard's will, states his intentions and places the responsibility for executing them on his brother, John:

I wish my Brother out of my Property to apply such sum as he shall think fit in the better endowment of the Church of Jackfield, on condition that Jackfield be formed into a distinct District. The income should not be less that £150 per annum. And I wish this appropriation to be considered as in memory of our late revered Father, who felt gratefully attached to Broseley Parish and that it should be so expressed in some Parish Record as to show that it arose from his property, and was a provision for the spiritual wants of a portion of our parish, which we know he would very much approve. [Broseley Parish Register, by kind permission of the Rev. Michael Kinna.]

His wishes were respected and a new church, known as St Mary's, was erected by public subscription to perpetuate his memory. It was built at Calcutts in 1863 on land given by Francis Harries of Cruckton, owner of Broseley Hall. The architect was (Sir) Arthur William Blomfield (1829-1899). It was a small church, intended to look rich as Pevsner observed, "by the use of pale red, strong red, yellow and blue bricks, and stone dressings" (Shropshire 158). In his History of Broseley John Randall described it as a "handsome little structure" [...] in which "the service is usually [...] bright and cheery, and such as draws good congregations" (217-28).

The arrangements for continuing financial support – the endowment – were recorded in the Parish Book. The income in 1865 totalled £188.19s. 4d., of which £20 was charged on the Estate of Francis Harries Esquire in Broseley; £20 from the rent of a farm in Melverly purchased with money from Queen Ann's Bounty; £24. 10s. from tithes of Jackfield District given up by the rector of Broseley. In addition the annual interest (£104. 9s.4d.) on the following investments:

£1500 sterling appropriated by John Pritchard Esquire M.P., according to the wish of his Brother, from money which belonged to their late revered Father, and from regard to his memory. £1500 given by the Ecclesiastical Commissioners of England to meet the first named £1500, and the two sums, making together £3000, being invested by the commissioners, now pay to the Cure annually the sum of £104.9s.4d. [Broseley Parish Register]

George Pritchard was Mayor of Much Wenlock in 1853; his name is engraved in the oak panelling in the Guildhall. His name is also recorded as a donor and contributor to the Library of the Wenlock Agricultural Society housed in a room above the Corn Exchange in the High Street.

Font in St Leonard’s Church, Bridgnorth carved by Thomas Earp. Photograph 2007 by the author.

The memory of both Pritchard brothers is commemorated in St Leonard’s Church, Bridgnorth. On entering the red sandstone church, through the south door, the visitor is drawn towards an elaborately carved, octagonal, two-tiered, alabaster Italianate font, on a stepped pedestal, elaborately carved by the great Victorian craftsman Thomas Earp of Lambeth. Earp was one of the finest craftsmen of the day and the favourite sculptor of the neo-Gothic architect George Edmund Street (1824-1881). In 1862, a magnificent marble pulpit designed by Street and carved by Earp was exhibited at the Great International Exhibition at South Kensington. It was highly praised in the Building News: "No finer work ever came from Mr Street's hands, no better carving ever left Mr Earp's" (Quoted Blachford 13). This fine pulpit and a font by Earp are in St Peter's Church, Bournemouth. His font in St Leonard's has eight figures, each standing on a serpent, around the upper tier – a bishop, king, mechanic, maiden, soldier, sage, an old woman and a merchant – symbolising Government, Wealth, Progress and Life. At the front of the font is a figure holding a bible in one hand, and a chalice in the other, a symbol of the Church as teacher and priest. This is an impressive memorial to John Pritchard and his wife, with the following inscription on the brass plaque at the base: "To the Glory of God in memory of John and Jane Pritchard, this font, the gift of William Pritchard Gordon, June 24th 1894". The tall, pinnacled font cover, the work of J. Phillips, was added later in 1911.

John Pritchard's obituary was published in the Shrewsbury Chronicle of 21 August 1891, page 8:

BRIDGNORTH. Death of Mr. John Pritchard. We regret having to announce the death of Mr. John Pritchard, D. L., J. P., of Stanmore, near this town, which occurred at his residence on Wednesday afternoon last. The deceased gentleman was senior partner in the late banking firm of Pritchard, Gordon, Potts & Shorting, of Broseley and this town; who in 1889 amalgamated with Lloyds Bank. The deceased was within a month of attaining the patriarchal age of 95, and has until a few months ago led a wonderfully active life. Mr. Pritchard was ever ready to further any philanthropic object with his purse and personal attention, and took a fatherly interest in the welfare of the inmates of the Quatt Industrial Schools whom Mr. and Mrs. Pritchard were often in the habit of entertaining at Stanmore. Up to the time of his decease Mr. Pritchard was a valued member of the Board of Management of the South East Shropshire School District. Mr. Pritchard was also on the Commission of the Peace for the county, and a magistrate for the borough of Wenlock (although not acting as such of recent years), and forty years ago represented Bridgnorth in Parliament jointly with Mr. Henry Whitmore from 1853 to 1866 [recte 1868]. The deceased leaves a widow, but no family.

Last modified 12 March 2020