'Whole picture-galleries of dreams' — Works 17.208

hen John Brett discovered that his hard work and technical accuracy simply meant another kind of failure, he might well have asked the question anticipated by Ruskin in Modern Painters 3: ‘Well, but then, what becomes of all these long dogmatic chapters of yours about giving nothing but the truth, and as much truth as possible?' Ruskin’s answer was: ‘The chapters are all quite right. “Nothing but the Truth,” I say still. “As much Truth as possible,” I say still. But truth so presented that it will need the help of the imagination to make it real’ (5.185)

The accurate study of fact is only the first stage of the creative process; what really mattered for Ruskin was the artist’s use of fact. He had always held that it was a narrow achievement merely to create a mimetic version of reality. From the outset he said that there were higher levels of truth, ‘of impression as well as of form, — of thought as well as of matter,’ and these truths might be conveyed completely independently of natural fact, ‘by any signs or symbols which have a definite signification in the minds of those to whom they are addressed, although such signs be themselves no image nor likeness of anything’ (3.104). The result is a system of three orders of truth: the truth of fact, the truth of thought, and the highest truth, the truth of symbol. The ideas in Modern Painters follow this same progression; in this chapter we are concerned with the second and third orders of truth.

Although Ruskin’s three orders are marked out in Modern Painters 1, the attention to the truth of fact in that volume obscures the other two. The need to defend Turner against specific attacks — that his paintings had imaginative power, but no resemblance to nature whatsoever — demanded this concentration on Turner’s meteorological and geological accuracy. In Modern Painters 2 the position was different:

It is the habit of most observers to regard art as representative of matter, and to look only for the entireness of representation; and it was to this view of art that I limited the arguments of the former sections of the present work, wherein, [65/66] having to oppose the conclusions of a criticism entirely based upon the realist system, I was compelled to meet that criticism on its own grounds. But the greater parts of works of art, more especially those devoted to the expression of ideas of beauty, are the results of the agency of the imagination. [4.165]

How to define the means by which the higher truths were achieved turned out to be a long and intriguing problem.

There is a further reason why the imagination is neglected in the first volume of Modern Painters. When he began, Ruskin was not sure what it was. Nearly eighteen months after Modern Painters 1 had made its appearance, we find him writing to one of his former tutors at Christ Church, H. G. Liddell, ‘can you tell me of any works which it is necessary I should read on a subject which has given me great trouble — the essence and operation of the imagination as it is concerned with art? Who is the best metaphysician who has treated the subject generally, and do you recollect any passages in Plato or other of the Greeks particularly bearing upon it?’ (3.670). Liddell suggested Aristotle, which may have given him the idea of using theoria for the perception of beauty, but Ruskin needed something more than a few quotes from Greek philosophers.1

We can see the problem being worked out in his drawings. He was perfectly well aware that somehow Turner penetrated the facts of outward experience and so transformed them, but he was not sure how. In 1841, while in Southern Italy, Ruskin had made a stylish but straightforward drawing of Amalfi.

Amalfi, 1841. John Ruskin. An efficient souvenir sketch of the Italian tour of 1840-41. Compare this on-the-spot drawing (D1.164) with the attempt to transform it into a Turnerian water-colour, ill. 3.

The topographical approach hardly conveys the glory of the scene which he noted in his diary at the time, ‘the light behind the mountains, the evening mist doubling their height’ (D1.164). On his return to England he was asked to do a more elaborate water-colour based on the sketch. The result, which was not finished until 1844, is a full-scale pastiche of Turner’s style (ill. 3). The sunset, moonrise and evening mist in blue, yellow and pink are straining for the poetic effect that these elements could achieve in Turner’s hands, but the result is very near caricature. This and other Turnerian fantasies of the period show Ruskin as it were trying to understand Turner from the outside, manipulating the devices, but unable to bring them to life. When in 1848 Clarkson Stanfield (one of the artists dropped in the revised Modern Painters 1) showed his picture of Amalfi at the Royal Academy, Ruskin wrote: ‘the chief landscape of the year, full of exalted material, and mighty crags, and massy seas, grottoes, precipices and convents, fortress-towers and cloud-capped mountains, and all in vain, merely because that same simple secret has [66/67] been despised; because nothing there is painted as it is!’ (4.337) It was exactly the same dilemma he had been in himself.

Illustration 3. John Ruskin, Amalfi, 1844. A full-scale attempt to imitate Turner's later manner, based on a drawing of 1841 (illustration 23).

The apparent conflict between fact and expression could be resolved, not by metaphysical speculation, but only by a concrete experience, something that depended as much on the evidence of his own eyes as on any intellectual reasoning. Once again, the key event is the tour of Italy in 1845. We have seen how important the tour was in hardening his attitude against the picturesque; it was also the moment of breakthrough for his positive theories of art. As I said earlier, Ruskin did not know a great deal about art history when he began Modern Painters, and the purpose of the tour was to fill in the wide gaps in his knowledge. In particular his ignorance of pre-Renaissance painting had been shown up by his reading of the French critic Alexis Rio’s The Poetry of Christian Art.2

Rio took the view that the Italian Renaissance, far from being a great cultural awakening, had destroyed the pure religious art of the medieval Italian Primitives, and had opened the way for decadence and decay. This attitude coincided with Ruskin’s own, for he wished to restore the religious basis of art. The conflict between his Protestant views and the Roman Catholic celebrations of Saints and Madonnas was resolved by the fact that these were pre-Reformation as well as pre-Renaissance, when the stream of pure religion was still clear and undivided. At the same time, Rio’s condemnation of the Renaissance fitted his own view of art history, for had not the Renaissance led to the despised painters of the seventeenth century, Poussin, Claude and Salvator Rosa? What he thought would be the completion of Modern Painters was therefore postponed until he had studied the early Italian schools, and he left for the Continent intending to show that religion ‘must be, and always has been, the ground and moving spirit of all great art' (3.670).

The tour opened up more lines of enquiry than he could follow, and ensured that the completion of Modern Painters was postponed even further. At Lucca he began his first serious study of architecture and sculpture, and he continued it at Pisa, where he also studied the medieval frescoes in the Campo Santo. The neglect and even active destruction of buildings and works of art made him frantic; he wanted to preserve everything he saw, by drawing it, or making daguerreotypes, and he even carried pieces of church away in his pockets. The picturesque pleasures of decay were far from his mind. At the same time he was becoming more politically aware, and reading Sismondi’s Histoire des républiques italiennes du Moyen-Age confirmed his view of the Renais-[67/68]sance as an end, rather than a beginning.3 Above all, the new artists that he seemed to discover every day showed how narrow his previous knowledge had been.

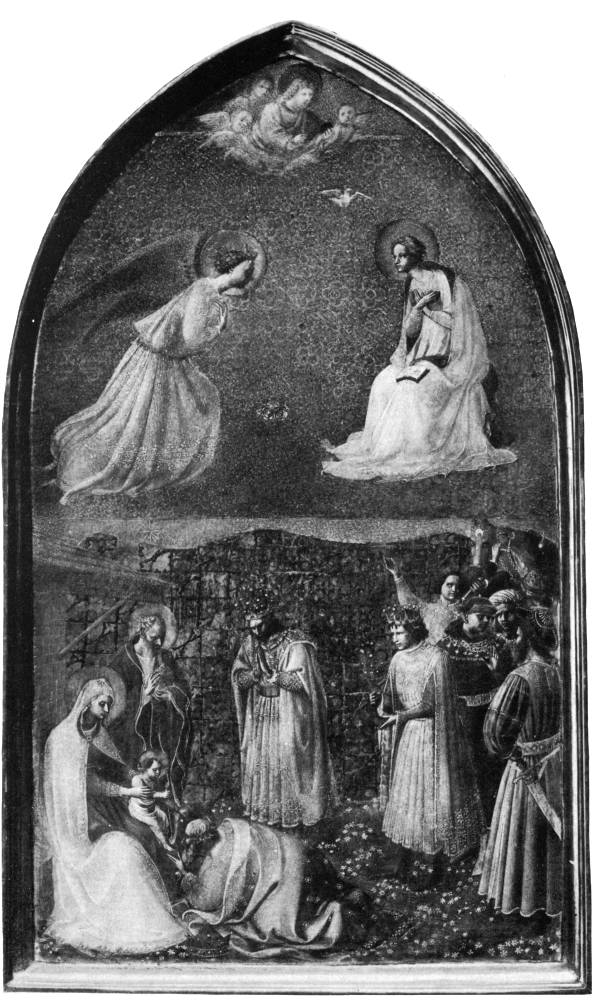

Enthusiasm for the new world of Italian Primitive art reached a climax in Florence, before Fra Angelico. He set himself to copy Angelico’s Annunciation and Adoration of the Magi, though he knew he would never be able to capture the jewel-like quality of the surface: ‘The whole background is solid with gold, so wrought up with actual sculpture that he gets real light, not fictitious, but actual light, to play wherever he wants’ (L45.102). If Turner was the master of light in the natural world, here was the symbolic expression of the light within men’s souls.

The work in Florence left him exhausted, and he retired to the mountains, aware of the new problem of how to reconcile the expressive truth of Turner with the iconographic truth he saw in the Italian Primitives. From his retreat at Macugnaga he wrote to his father: ‘I had got my head perfectly puzzled in Italy with the multitude of new masters and manners and I was getting a little adrift from my own proper beat, and forgetting nature in art — now I am up in the clouds again’ (L45.164). Had he stayed in the mountains, he wrote in his autobiography forty years later, he might have written The Stones of Chamonix instead of The Stones of Venice. However, his geological studies, so important for the defence of Turner, were broken off in order to go to Venice with his former drawing-master, J. D. Harding. He seems to have been unprepared for what was in store: he told his father, ‘John and Gentile Bellini are the only people I care about studying here, my opinions about Titian and Veronese are formed, and I have only to glance at their pictures. . . .’ (L45.207).

Suddenly, he was writing home that he had been ‘overwhelmed today by a man whom I never dreamed of' (L45.210). Apparently in an idle moment he and Harding had gone to look at the enormous series of religious pictures painted by Tintoretto to decorate the great halls of the Scuola di San Rocco. He was astonished by the breadth, energy and majesty of Tintoretto's work.

As for painting, I think I didn’t know what it meant until today — the fellow outlines you your figure with ten strokes, and colours it with as many more. I don’t believe it took him ten minutes to invent and paint a whole length. Away he goes, heaping hosChapter Four: Ruskin and the Imaginationt on host, multitudes that no man can number — never pausing, never repeating himself — clouds, and whirlwinds and fire and infinity of earth and sea, all alike to him —. [L45.212] [68/69]

His own study of Tintoretto’s Crucifixion conveys this sense of energy and movement with a dynamism completely lacking in his earlier picturesque sketches. It was a disturbing experience, the culmination of a long and exciting tour; and, after postponing his return to England in order to make this copy, he was ill nearly all the way home. In later life he never underestimated the value of what had happened, but there is sometimes a note of regret, as though the experience had been too profound, making demands on him which were not his ‘own proper work' (35.372). But it was the necessary personal experience enabling him to understand the inner workings of the creative imagination: ‘I had seen that day the Art of Man in its full majesty for the first time; and that there was also a strange and precious gift in myself enabling me to recognize it, and therein enobling, not crushing me’ (4.354).

John Ruskin, Copy of the Central Portion of Tintoretto's 'Crucifixion' in the Scuola di San Rocco, Venice, 1845. Ruskin told his father to put Tintoretto 'at the top, top, of everything' (L45.212) and his energetic copy shows the emotional effect of Tintoretto's demonstration of the penetrative imagination at work.

Ruskin’s positive theory of the imagination is by no means as simple as his negative theory of the picturesque. The ground plan, as laid out in the second half of Modern Painters 2, seems clear enough, but his theory raised as many problems as the experience in the Scuola di San Rocco seemed to resolve. It is a little alarming to find him announcing at the beginning of Modern Painters 3 that he is abandoning any attempt at a systematic approach, on the grounds that he can do better ‘by pursuing the different questions . . . just as they occur to us, without too great scrupulousness in marking connections, or insisting on sequences' (5.18). The result is much more expressive of Ruskin’s own enquiring imagination, but it does not make the exposition of his constantly developing ideas any easier.

The general terminology, at least, has been established in Modern Painters 2 2. Briefly, the theoretic faculty and the imaginative faculty are both concerned with the same problem, the apprehension and creation of beauty and truth; but they perform their functions differently. The theoretic faculty passively perceives, the imagination actively recreates. Imagination itself operates in three ways, each interacting with the other. First the penetrative imagination sees the object or idea in its entirety, both its external form and its inner essence. Then the action of the associative imagination enables the artist to convey this vision through some medium such as painting. The third faculty, the contemplative imagination, deals with remembered or abstract ideas, and so acts as a kind of metaphor-making faculty. As Ruskin’s theory develops, the three kinds of imagination find their correspondence in the three orders of truth. The penetrative imagination deals with external fact and the [69/70] inner truth it reveals, the associative imagination expresses the artist’s thought, and the contemplative imagination gradually evolves into a theory of symbolism.

All three functions of the imagination, together with the theoretic faculty, combine in the act of seeing — the visual dimension is vital throughout his argument.

All the great men see what they paint before they paint it, — see it in a perfectly passive manner, — cannot help seeing it if they would; whether in their mind’s eye, or in bodily fact, does not matter; very often the mental vision is, I believe, in men of imagination, clearer than the bodily one; but vision it is, of one kind or another, — the whole scene, character, or incident passing before them as in second sight, whether they will or no.

He quotes the words of Revelation; ‘Write the things which thou hast seen, and the things which are’ (5.114).

The concept of the imagination as a predominantly visual faculty came down to Ruskin through the psychology of Hobbes and Locke, whose works he had read at Oxford, and through the popularization of their views by Addison and Johnson. The eye was regarded as the chief source of information to the brain, and so ideas tended to be treated as visual images. Towards the end of the eighteenth century Romantic theory began to move towards an image of the mind as a container for various emotional states, rather than a picture-book or mirror. The image of the mirror, derived from Plato, was supplanted by one of organic growth, so that the mind, instead of reflecting the outside world (albeit in a rather special way), imposed itself upon it. The link between mind and the outside world was made by the emotions, the vehicle of that ‘something far more deeply interfused’ described by Wordsworth; the result was an identification between the perceiving subject and its object. Coleridge coined the word ‘esemplastic’ to describe this unifying process. Ruskin preferred the older visual theory but still had somehow to come to terms with the role of the emotions. This was the problem in his theory of beauty: he insisted that beauty was objective, and yet he had to acknowledge that there was a sympathetic identification between the perceiver and what he saw, particularly as far as vital beauty was concerned. He now found himself in danger of reducing the objectivity of imaginative perception in the same way, by giving too much room for emotional response.

The answer was to try to have things both ways:

There is reciprocal action between the intensity of moral feeling and the power of imagination; for, on the one hand, those who have keenest sympathy [70/71] are those who look closest and pierce deepest, and hold securest; and on the other, those who have so pierced and seen the melancholy deeps of things are filled with the most intense passion and gentleness of sympathy. [4.257]

Seeing and feeling combine. It was natural that Ruskin should stress the older visual theory. After all, in his own case the eye was the chief source of information, both by inclination and training — and any abstract theory would be subordinate to his ‘sensual faculty of pleasure in sight, as far as I know unparalleled’ (35.619).

Clear seeing, of course, was one of the requirements for the correct apprehension of the facts of nature; indeed, ‘the sight is a more important thing than the drawing’ (15.13); but there must be no confusion between the expression of a mimetic reality and of a true perception. This was what Tintoretto had taught him in the Scuola di San Rocco; for ‘the effect aimed at is not that of a natural scene, but of a perfect picture’ (11.404). The true artist neither falsifies his perception nor tries to reproduce reality. His sight is insight. Tintoretto demonstrates

the distinction of the Imaginative Verity from falsehood on the one hand, and from realism on the other. The power of every picture depends on the penetration of the imagination into the TRUE nature of the thing represented, and the utter scorn of the imagination for all shackles and fetters of mere external fact that stand in the way of its suggestiveness. [4.278]

Without the close study of external fact our imaginative process would be false or useless, since we would not know what we are dealing with; but the inner truth is paramount.

This, the penetrative imagination, can be seen at work when a great artist manages to suggest more than he has actually put on his canvas. Appropriately, he turns to Tintoretto's Crucifixion, where he finds two masterly examples. To begin with, most Crucifixion scenes (he is thinking of the Renaissance and after) are blasphemous, distorted by their anatomical concentration on the suffering body of Christ. By contrast Tintoretto has made the figure of Christ quite still, depicted at the moment of resignation to this pain. But to express this stillness the rest of the picture is filled with violent action — we can see how Ruskin has tried to convey in his copy the central vertical figure with radiating lines of energetic movement surrounding it. Thus physical agony is expressed by its opposite, repose, one of Ruskin’s forms of typical beauty. The penetrative imagination is even better exemplified by the figure on an ass behind and to the left of the Cross. Tintoretto wished to convey not just the brutality of the event itself, but the [71/72] rejection of Christ by his people. Therefore, Ruskin points out, the ass is eating withered palm leaves, the palm leaves that had greeted Christ on his triumphal entry to Jerusalem five days before.

To bring the leaves of Palm Sunday to Calvary does not conflict with Ruskin’s argument for fact. He insists that the imagination is not creative, merely the arranger of the facts received, operating as a kind of second sight, ‘exalting any visible object, by gathering round it, in farther vision, all the facts properly connected with it' (5.355). But although Modern Painters 1 had established the case for fact against the conventionalized vision of the picturesque, he began to see that the argument for fact was threatened from another quarter. The problem was that the penetrative imagination might be too imaginative, — for instance, poets were the worst judges of painting, because their sensitivity was so great that it took only a slight suggestion to set their imaginations racing, with the result that the object itself was lost in the flow of indiscriminate feeling. We have to distinguish between the true appearance of things and their false appearance ‘entirely unconnected with any real power or character in the object, and only imputed to it by us’(5.204). If he was to uphold the objectivity of imaginative perception, subjective emotion had to be put in its place.

As I said earlier, Ruskin could not deny that there was an emotional identification between perceiver and perceived: indeed, ‘the Imagination is in no small degree dependent on acuteness of moral emotion; in fact, all moral truth can only thus be apprehended — and it is observable, generally, that all true and deep emotion is imaginative, both in conception and expression’ (4.287). But there is a difference between sensitivity, which helps us to experience accurately and truthfully the emotions of others, and the egoistical feelings of one’s own mind, which seek to impose themselves on everything around them.

To distinguish between true and false appearances induced by the selfish emotions Ruskin invented the term ‘the pathetic fallacy.’ We are in danger of making a pathetic fallacy whenever we allow our emotions to project themselves on to our surroundings. When in a moment of pain and grief we write of the sea as ‘the cruel, crawling foam’ (5.205), we are wrong, for foam is not cruel, nor does it crawl, it is simply foam. It is perfectly legitimate to express one thing in terms of another, but it is wrong to confuse them. When Dante describes the spirits of dead men falling ‘as dead leaves fall from a bough,’ this is in Ruskin’s view ‘the most perfect image possible of their utter lightness, feebleness, passiveness, and scattering agony of despair' (5.206),' but with Dante the emotion does not distort; he never loses sight of the [72/73] fact that ‘these are souls, and those are leaves, he makes no confusion of one with the other’ (5.206).

It is here that Ruskin parts company with the Romantic poets. For all that they were concerned with accurate perception free of idealizing emotions, their main interest was in how these perceptions affected their feelings. Their concern is with the natural world, but the world as a set of symbols that will reveal the truth of the poet’s inner nature. Coleridge believed that the perceiver and the object of his perception were moulded by the esemplastic imagination into one unity — for Ruskin this seemed an exaltation, not an annihilation of self. He too believed that the natural world contained a set of symbols, but the absolute and universal significance of these symbols was threatened if they were treated as the creation of a subjective mind. That was the problem of his chapter in Modern Painters 3, ‘The Moral of Landscape.’ How can the appreciation of landscape have any moral value at all, if it is merely looked on as a means of gratifying personal feelings ?

Ruskin was temperamentally as well as intellectually hostile to what Keats called ‘the egoistical sublime.’ His religious upbringing instilled self-denial, so that his mind was always directed out towards the greater glories of the universe. ‘A poet is great, first in proportion to the strength of his passion, and then, that strength being granted, in proportion to his government of it' (5.215). What was demanded of an artist was a dynamic balance between the opposing stresses of fact and emotional expression, one which would raise his work to the new level of truth.

It must be asked, however, whether or not Ruskin himself was guilty of a pathetic fallacy of another kind, whether or not the grand system of symbols he discovered in the universe was no more than what Henry Ladd calls the ‘emotional inreading of moral metaphor’ (189). It was all very well to say that the poet’s subjective emotions interfered with his perception of the order of God, but the moral order Ruskin perceived in the external world was a projection of his own religious views. Since he believed in the absolute existence of this order, even when he had abandoned the formal religion on which it was founded, he could not conceive of it as a projection; but, for all that he was intellectually convinced, it was as much a question of faith as of reason.

Assuming, then, that the penetrative imagination has provided the artist with a correct, instantaneous vision of truth, it is the work of the associative imagination to convey it to other people. The word ‘associative’ [73/74] is an unfortunate choice, for at first glance it suggests a connection with the theory of the association of ideas. By ‘associative’ Ruskin meant no more than bringing the separate parts of a picture or poem together. The associative imagination does the arranging — but not, as in the case of Claude’s Isaac and Rebecca, by simply selecting individually pleasing details regardless of their inter-relationship. Unlike the sterile art of classical composition, the shaping imagination creates a living and perfect unity out of imperfect parts. It is a restatement of the theory of the unity of membership in Modern Painters 2. This unity can only be seen when the disjointed parts are brought together, and it can only exist in that one form. In achieving it, man comes closest to the creative power of God.

It proved very difficult to explain just how it was that the imagination could create this perfect harmony of imperfect parts. The process worked precisely because there were no rules that it could follow. Ruskin gives a comic description of a picturesque artist trying to draw a tree according to the rules of composition, and failing, because he is afraid of spontaneity. But there is nothing that the imaginative artist dare not do, or that he is obliged to do. A practical demonstration of the interdependence of the separate elements of a picture is given with the aid of a plate from Turner’s Liber Studiorum, Cephalus and Procris. The reader is asked to cover up each part in turn, and see how in every case the change detracts from the unity of the whole.5

Cephalus and Procris. J. W. M. Turner. In Modern Painters 2 Ruskin demonstrates the operation of the associative imagination by instructing the reader to cover up each part of the plate in turn and observe the dependency of each section on the other. His instructions are quoted in full in note 5. [Click on image to enlarge it.]

The function of the associative imagination extends to the question of the purely formal arrangement of lines, shapes and colours on the canvas. This subject is never tackled seriously in Modern Painters, on the grounds that it is too difficult, though he adds: ‘Expression, sentiment, truth to nature, are essential: but all these are not enough. I never care to look at a picture again, if it be ill-composed’ (7.204). However, his teaching manual The Elements of Drawing (1857) does contain an excellent analysis of the general principles on which pictures may be constructed. His point is again that there are no rules. There is just the one principle of bringing all things towards unity, and this applies just as much on the technical, as on the expressive level. He demonstrates his acute visual sensitivity when he writes of the formal qualities of paint.

It is not enough that [lines and colours] truly represent natural objects; but they must fit into certain places, and gather into certain harmonious groups: so that, for instance, the red chimney of a cottage is not merely set in its place as a chimney, but that it may affect, in a certain way pleasurable to the eye, the pieces of green or blue in other parts of the picture. [15.163] [74/75]

Because Ruskin placed such emphasis on the moral significance of paintings, his awareness of their abstract qualities tends to be underestimated. What is important is his desire to unify the two: the ‘types’ of beauty symbolizing God are also formal qualities of art; conversely, the principles of composition which he discusses in The Elements of Drawing carry moral significance. ‘There is no moral vice, no moral virtue, which has not its precise prototype in the art of painting’ (15.118). When he planned a revision of Modern Painters in the 1870s he intended to include the section on composition from The Elements of Drawing.

Before going on to consider the highest of Ruskin’s three orders of truth, the universal system of symbols discoverable in all things, we are now in a position to see how he resolved the conflict between fact and expression. This was the question raised by his two drawings of Amalfi, or his criticism of John Brett’s landscape. He tackled the problem in the most practical way possible, by going to the Alps to find the actual spots where Turner had sketched, and comparing this phenomenological reality with Turner’s results. In 1843 Turner had produced a second batch of ‘delight-drawings’ in order to get commissions. Ruskin was especially struck by a sketch of the pass of Faido, on the Italian side of the St. Gotthard, where the coach road and the Ticino river run along the bottom of a gorge. He commissioned a finished water-colour and later bought the original sketch. In 1845, in spite of discouraging noises from Turner, he went in search of the actual spot, and made his own drawings. The results of this research are the basis of his brilliant chapter in Modern Painters 4, ‘Of Turnerian Topography,’ which forms a pendant to ‘Of the Turnerian Picturesque.’

The Pass of Faido (1st Simple Topography).. John Ruskin. Ruskin engraved this plate and its companion, The Pass of Faido (2nd Turnerian Topography), in Modern Painters 4 to demonstrate the difference between a topographical and an imaginative vision. [Click on image to enlarge it.]

Here the principles of the imagination are put into practice. ‘Painting what we see’ now has a much more subtle meaning. If we go to a place and see nothing more than what is there, then we must paint nothing more, and content ourselves to be topographers. But ‘if going to the place, we see something quite different from what is there, then we are to paint that — nay we must paint that, whether we will or not; it being, for us, the only reality we can get at’ (6.28). As topographers we must aim at mimetic reality, but the impression produced by an object seen with the penetrative imagination can never be included within the limits of a picture. The artist must add or subtract in accordance with his insight. In this case the trees in the pass detract from the height of the valley walls, so Turner omits them, to dramatize the dangers of avalanche. The bridge which stands too solidly in the foreground is moved back, in order to concentrate the spectator’s eye [75/76] on the smashing force of the river. River and road are shown in conflict of the valley floor. The road has bumped and twisted its way all over the St. Gotthard pass, so here, on the right, it is made to bump and twist, recalling past and future conditions of the route. To show the perseverance of the road in its struggle with the river, the transport shown is not a powerful diligence but a light coach drawn by a pair of ponies. Ruskin gives particular attention to the buttressing of the road on the right, arguing that this is a detail from a sketch made higher up the pass. It had been made thirty years before, yet such is the power of Turner’s imaginative vision that this key detail is unconsciously selected from the mass of material retained in his memory.

The Pass of Faido (2nd Turnerian Topography).. John Ruskin. Ruskin engraved this plate and its companion (above) in Modern Painters 4 to demonstrate the difference between a topographical and an imaginative vision. [Click on image to enlarge it.]

The sum total of Turner’s version of the scene amounts to a kind of ‘dream vision.’ Obedience to the primary perception of the penetrative imagination meant that no selfish notions of his own powers interfered with communicating the truth of the scene. The associative imagination allowed no modifications according to artificial ideas of composition; only the one unified experience has been conveyed, not as an indulgence of the artist’s emotions, but as an expression of the far greater significance of the pass itself. More and more, Ruskin felt that the true force of the imagination

lies in its marvellous insight and foresight, — that it is, instead of a false and deceptive faculty, exactly the most accurate and truth-telling faculty which the human mind possesses; and all the more truth-telling, because in its work, the vanity and individualism of the man himself are crushed, and he becomes a mere instrument or mirror, used by a higher power for the reflection to others of a truth which no effort of his could ever have ascertained. [6.44]

The Pass of Faido.. John Ruskin. 1845. Ruskin's on-the-spot drawing shows that his own immediate response to the scene was nearer Turner's than a topographer (6.34-41). [Click on image to enlarge it.]

If Modern Painters 1 constitutes Ruskin’s argument for fact, then the sections I have cited from Modern Painters 2, 3 and 4 constitute his argument for truth in the material world. We now have to consider the final, transcendental truth of the symbolic imagination.

In the last resort, Ruskin would have said that the process of the imagination was incapable of complete explanation. The process was not rational, and all he could do was to try to describe the operation of some of its functions. He asserted repeatedly against those who would impose rules on art that creativity was unteachable; it was a divine gift which could only be damaged or wasted, never improved, while it was often used quite unconsciously by those who had the facility. Towards the end of Modern Painters 5, after making an analysis of a Turner drawing in similar terms to the one we have just discussed, he concluded: [76/77] ‘I repeat — the power of mind which accomplishes this, is yet wholly inexplicable to me, as it was when first I defined it in the chapter on imagination associative, in the second volume’ (7.244).

The issue we are concerned with is the evolution of Ruskin’s symbolism; the difficulty is that this is a two-way process. In one direction, as critic, Ruskin becomes more and more aware of the importance of symbolic expression in art; in the other direction, as it were, as an artist in his own right, he is evolving his own private symbolism, in parallel with the universal system he discovers. His Evangelical training had of course ensured that symbolism was an inherent part of his theories — hence his theory of typical beauty — but it was insufficient to point simply to the existence of God-given types. In his search for a unified theory of art he had to explain how man too could convey the eternal truths of the Creation: he had to say more than just ‘there is in every word set down by the imaginative mind an awful under-current of meaning, and evidence and shadow upon it of the deep places out of which it has come’ (4.251). This description, suggestive of a journey into the unconscious mind, shows him fumbling for words to convey that special quality of perception which only the truly creative imagination could have.

Of the three chapters on the imagination in Modern Painters 2 the third, ‘Of Imagination Contemplative,’ is by far the weakest. The contemplative imagination is concerned with objects that could not be tested by visual perception, either because they were abstract ideas or because they were memories of objects once seen. Such ideas can be conveyed visually in two ways: either by presenting just one aspect of the idea, as an abstract indication of the rest, or symbolically, by substituting a different object altogether to represent the idea. At its simplest level the contemplative imagination acts as a metaphor-making faculty; but its function as originally defined by Ruskin can be applied to the most complex processes of symbolization.

Depriving the subject of material and bodily shape, and regarding such of its qualities only as it chooses for particular purpose, [the imagination] forges these qualities together in such groups and forms as it desires, and gives to their abstract being consistency and reality, by striking them as it were with the die of an image belonging to other matter, which stroke having once received, they pass current at once in the peculiar conjunction and for the peculiar value desired. [4.291]

The idea that the imagination can be totally free of the limitations imposed on the representation of natural fact opens the way to a completely [77/78] abstract or symbolic art; but Ruskin does not for the moment develop the idea in that direction. Instead he is concerned with problems of formal abstraction: how, for instance, a monochrome drawing suggests colour, or how colour dissolves outline. He does not even treat the contemplative imagination as a faculty in its own right, but as a subordinate function of the other two. The full implications of his theory have not been developed.

The problem however remained, and in the third volume of The Stones of Venice (1853) he came much nearer to a resolution. The way his ideas evolve is typically Ruskinian, and it is necessary to follow it in some detail. The discussion develops from the grotesque> carvings which decorate Venetian and other churches. Concerned with the social as well as the artistic decline he detects in the Venetian Renaissance, he takes one grotesque head on the church of Santa Maria Formosa — ‘huge, inhuman, monstrous, — leering in bestial degradation’ (11.145) — as symptomatic of the city’s moral collapse. Since he must distinguish between the grotesques of the Renaissance and the grotesque carvings of the Gothic period, which he considered noble, a general discussion of the grotesque genre ensues. It is an approach, from a different angle, to the same problem of abstraction and symbolism, for grotesques could not be taken as direct representations of anything, but they were not purely decorative objects either.

Ruskin suggests two basic motives for producing any kind of such work: a sense of humour, or a sense of fear, two irrational elements which have legitimate functions in art. Play is a necessary and healthy activity, a relaxation, free from the strict demands of accurate delineation, and a positive virtue in the grotesque: ‘its delightfulness ought mainly to consist in those very imperfections which mark it for work done in times of rest’ (11.158). (Provided, that is, that these imperfections are distinguished from those of the picturesque.) In its playfulness, the grotesque involves a necessary amount of abstraction. When it comes to the grotesque as an expression of fear, then there is a necessary element of symbolism.

Ruskin shows his religious training when he says that the fear that inspires the grotesque is the fear of sin, and the fear of death. As an irrational emotion, fear can distort the normal and relatively ordered functioning of the imaginative faculties, but he also suggests that an irrational element may appear when the mind is overcome by the sheer power of what it is asked to conceive, what he calls ‘the failure of the human faculties in the endeavour to grasp the highest truths’ (11.178). The result will be a grotesque — a symbol. Almost by accident, Ruskin [78/79] has reached the central problem in his analysis: how these higher, unspeakable, overpowering truths are perceived and conveyed. He sees a connection between the ‘ungovernableness’ of the imagination under the influence of fear, and the whole question of the non-rational and inexplicable working of the creative mind. Not only the grotesque, but ‘the noblest forms of imaginative power are also in some sort ungovernable, and have in them something of the character of dreams; so that the vision, of whatever kind, comes uncalled, and will not submit itself to the seer, but conquers him, and forces him to speak as a prophet, having no power over his words or thoughts’ (11.178). Ruskin was saying, in very similar words, the same thing in the conclusion to his analysis of The Pass of Faido: the imagination is greater than the man.

To account for the difficulty the mind has in grasping the highest truths, Ruskin is led to set up an experimental model of the mind. True to his visual theory of the imagination, he uses the Platonic image of the mirror. Unlike Romantic ideas of the mind, this traditional image carried none of the overtones of emotional projection which he was so anxious to avoid. The mind must be a mirror, for its purpose was to reflect the greater glory of God, God in this sense as external to man and the universe. But his evangelical training taught him that the image the mind of man received was both dim and distorted, dimmed by selfishness and pride, distorted by the sheer size of what it was called upon to convey. ‘The fallen human soul, at its best, must be as a diminishing glass, and that a broken one, to the mighty truths of the universe round it’; therefore, in so far as the artist can see clearly (the visual imagery is consistent throughout his argument), he may perceive these truths clearly; but in so far as his vision ‘is narrowed and broken by the inconsistencies of the human capacity, it becomes grotesque’ (11.181). This is the rationale not only for symbolism in art, but also for the symbolic interpretation of the natural world, for ‘the whole visible creation’ (11.183) becomes ‘a mere perishable symbol of things eternal and true.’

In the light of what has been said about the influence of typology on Ruskin’s theories it is significant that he proceeds to build upon his argument by examining the treatment of dreams in the Bible. The ladder in Jacob’s dream signified the ministry of angels, but such a conception was too vast for him, so it was presented as a ladder, that is, ‘a grotesque’ (11.181). We are a long way from the carving on the church of Santa Maria Formosa in Venice, and Ruskin has to admit it himself, for he concedes, ‘such forms, however, ought perhaps to have been arranged under a separate head, as Symbolical Grotesque’ (11.182). [79/80]

In comparison with the dense and curiously evolved argument in The Stones of Venice, Ruskin handles symbolism with much more confidence in Modern Painters 3. There is a much clearer definition of what he now means by a grotesque: ‘the expression, in a moment, by a series of symbols thrown together in bold and fearless connection, of truths which it would have taken a long time to express in any verbal way’ (5.132). Symbolism now has much greater importance in his general scheme of art. Previously his principal divisions had been two: the Purist School, chiefly the early Italian painters, who were morally sound but limited in scope because they worked by abstraction; and the Naturalist School, whose stars were Turner and Tintoretto, which combined realistic depiction with imaginative perception. The Grotesque was added as a third category in its own right, which, since it included painters who worked by personification or allegory as well as those trying to present symbolically the ‘highest truths,’ could include most painters. Allegory and personification had always been treated as legitimate tools for the painter (provided their purpose was sound and their use imaginative rather than conventional); now they fitted into the overall moral system.

The consequence of the development of a rationale for symbolism was that there was now a second argument for the defence of Turner. The artist, because of the greater powers of his imagination — or, if you like, because of his clearer and less distorted mind-mirror — was the man best able to perceive the highest truths symbolized in the natural world. The artist becomes a mediator between God and ordinary man. Frequently the artist is associated with the preacher — and the prophet. In the first edition of Modern Painters 1 Ruskin’s enthusiasm had led him to say that Turner was ‘sent as a prophet of God to reveal to men the mysteries of His universe, standing, like the great angel of the Apocalypse, clothed with a cloud, and with a rainbow upon his head, and the sun and stars given into his hand’ (3.254). (Blackwood’s Magazine suggested this might be blasphemous and the reference disappeared in later editions.) By linking painting with prophecy Ruskin was building on the theological tradition in which he had been brought up, but in doing so his intention was not to restrict art to some narrow Evangelical doctrine; this was no longer possible, as we shall see. Rather, he wished to justify art as the highest activity possible for man, and enable it to range freely over the multiplicity of truths open to the artist’s vision. Art had to become revelation. [80/81]

In my introduction I quoted Ruskin’s description of his work as a tree. With the end of this chapter we come to a natural division in the progress of that work, the conclusion of Modern Painters in 1860. This division is not a complete break, but a branching-off point, as themes already inherent become established in their own right, without losing any continuity with the central core of ideas. I have followed the development of his attitude to Turner as one of the linking themes of the first period, and there can be no better example of the organic evolution in Ruskin’s writing than the way his analysis of Turner, which began in Modern Painters 1 firmly rooted in natural fact, ends in Modern Painters 3 with a discussion of symbolism. The very last works of Turner that he considers are not the landscapes which first fired his enthusiasm, but two allegorical works, The Goddess of Discord Choosing the Apple of Contention in the Garden of the Hesperides (ill. 27) and Apollo and Python (ill. 5).

Illustration 27. J. M. W. Turner, The Goddess of Discord Choosing the Apple of Contention in the Garden of the Hesperides, 1806. In the foreground the Goddess receives the apple from one of the Hesperides, in the background is the dragon Ladon. Ruskin was chiefly interested in the dragon, which he interpreted in mythological, geological and sociological terms.

The analysis of these paintings reveals both a different Ruskin and a different Turner from those of seventeen years before. A technical reason for Ruskin’s developed interpretation was that before writing his concluding volume he had for the first time seen the whole of Turner’s work.

Illustration 25. J. M. W. Turner, Apollo and Python, 1811. For Ruskin the victory of good over evil, of light over darkness: ‘Colour . . . is the type of love’ (7.419).

Turner died in 1851. In his will he left his works to the nation, intending that they should be gathered together in a special Turner Gallery, but the will was confused and his wish has never been carried out. Ruskin resigned as an executor of the will, but in 1857 he secured the job of cataloguing the nineteen thousand-odd Turner drawings lying in the cellars of the National Gallery. This he did in the winter of 1857-58, writing a report and a catalogue for fifty sketches which he selected for display. This opportunity to survey all of Turner’s work led him to give a much gloomier picture of Turner’s mind than he had done up to now. In Modern Painters 1 he had spoken of Turner’s last works as dark prophecies which admitted the impossibility of achieving his aims; and now, in Ruskin’s final pages, pessimism, encapsulated in the title for Turner’s poems, ‘The Fallacies of Hope,’ becomes the dominant note. This view of Turner is in accordance with modern opinion; he was a pessimist, but the changed and darker world picture that now emerges at the end of Modern Painters 3 is as much Ruskin’s as Turner’s.

The choice of these two particular paintings with which to conclude Modern Painters shows how significant imaginative symbolism had become for Ruskin, but it is important to see how the underlying themes of natural fact and creative expression still function as orders of truth within the overall structure. The Garden of the Hesperides (1806) is an opportunity for Ruskin to exercise his increasing interest in the [81/82] Greek myths; and the reader is treated to an elaborate, and at first confusing, account of the mythological sources for the subject of the painting. Ruskin’s mythography is both a critical tool and an imaginative creation in its own right. Not only does he compound all the classical mythographers from Homer to Pausanias without distinguishing their value as sources; he also treats Biblical reference, Dante, Spenser, Milton, Shakespeare and sometimes later sources as one continuous body of poetic meaning, as ‘a Sacred classic literature’ (33.119). His interpretation of myth, though, is consistent with the orders of truth on which all his criticism is founded.

Myth is treated as existing on three levels, ‘the root and the two branches’ (19.300). On the first level it is an expression of natural phenomena; on the second it is the personification of an idea; and lastly it holds ‘the moral significance of the image, which is in all the great myths eternally and beneficently true’ (19.300). Ruskin is not particularly concerned whether or not Turner consciously assembled his classical references in The Garden of the Hesperides in the precise pattern he detects. As a great prophetic artist, Turner unconsciously partakes of the great tradition of physical and moral imagery. Take for example the smoke-breathing dragon which lies along the crest of the background hills. According to the ancient sources, the garden of the Hesperides was set on the Mediterranean coast of Africa, sheltered by mountains from the hot winds of the Sahara. The dragon, therefore, is the desert wind, the Simoon, marking the limit of vegetation represented by the garden. At the same time the dragon is related, according to Ruskin’s mythography, to Medusa, whose face could freeze men to stone. The dragon clutches the mountainside, as stone, and as ice, for if Ruskin ‘were merely to draw this dragon as white, instead of dark, and take his claws away, his body would become a representation of a great glacier, so nearly perfect, that I know no published engraving of glacier breaking over a rocky brow so like the truth as this dragon’s shoulders would be’ (7.402). The dragon is therefore wind and ice, and yet simultaneously Ruskin suggests that its jaws are modelled on those of a Ganges crocodile. This is the truth of natural fact with which Ruskin had begun his defence of Turner.6

Although Ruskin is confident that Turner had intended the dragon to represent the hot winds of Africa, Ruskin’s point is that ‘the moral significance of it lay far deeper’ (7.393). The dragon that guards the tree in Hesiod’s account of the Garden of the Hesperides is linked with the serpent in the Garden of Eden. As Ruskin traces the mythological connections through Virgil and Dante, the dragon becomes the symbol [82/83] of fraud, rage, and gloom (7.401), with final significance as ‘the evil spirit of wealth’ (7.403). Thus the natural fact of the herpetological accuracy of the dragon’s jaws conveys a higher expressive truth. But the coherence between natural fact and symbolic expression is not limited to the internal symbolism of this one picture. A structure whose meaning is ‘eternally and beneficently true’ must also have external, universal reference. To stress this eternal significance Ruskin calls The Garden of the Hesperides a religious picture, and draws from it a particular meaning for his own time: ‘Such then is our English painter’s first great religious picture; and exponent of our English faith. A sad-coloured work, not executed in Angelico’s white and gold; nor in Perugino’s crimson and azure; but in a sulphurous hue, as relating to a paradise of smoke. That power, it appears, on the hill-top, is our British Madonna’ (7.407-08). The greedy jaws of the dragon are Victorian society’s passion for material wealth, his smoke is from the furnaces of Industrial England.

A system of symbols with both particular and universal reference must necessarily also have continuity from one work of art to another. In this case the serpent-dragon of Apollo and Python (1811) is the connecting link. Here Ruskin spends less time on the mythological significance of the story and goes straight to the central meaning of the work: the archetype of the conflict of light and dark. None the less the process of revealing this central meaning passes through the same progression of natural fact, individual expression and universal symbol.

Ruskin’s analysis of the two paintings is linked by the problem of light. The change between the ‘sad-coloured’ Hesperides and the flashes of light in the background and sky of the Apollo ‘is at once the type, and the first expression of a great change which was passing in Turner’s mind. A change, which was not clearly manifested in all its results until much later in his life; but in the colouring of this picture are the first signs of it; and in the subject of this picture, its symbol’ (7.409). The context of this first hint of Turner’s later colour style is taken as an image for the critics’ rejection of his later colouristic works. The scarlet in these clouds is defended in the same way as those later works were defended in Modern Painters 1, by an appeal to observation: ‘One fair dawn or sunset, obediently beheld, would have set them [the critics] right; and shown that Turner was indeed the only true speaker concerning such things that ever yet had appeared in the world’ (7.412). The phrasing echoes the geological defence of Turner seventeen years before. [83/84]

It is significant that colour should play such an important part in Ruskin’s final discussion of Turner in Modern Painters. Although he had been sensitive to the question of colour throughout the work, he had had difficulty in integrating the problem with the main thread of his argument. Ruskin acknowledges the fact by introducing a footnote of several pages at this point, to try to pull his scattered references together. It seems that the structure of symbolism he was evolving gave him the confidence to deal with the problem. Thus we have a colour as an accurately observed natural fact, as symbolic of the change in Turner, and then as a reverberating image with a multiplicity of meanings. Scarlet is the colour of light passed through the earth’s atmosphere; it is the colour of human blood; it is the Hebrew symbol of purification. All light has symbolic value:

as the sunlight, undivided, is the type of the wisdom and righteousness of God, so divided, and softened into colour by means of the firmamental ministry, fitted to every need of man, as to every delight, and becoming one chief source of human beauty, by being made part of the flesh of man; — thus divided, the sunlight is the type of the wisdom of God, becoming sanctification and redemption. Various in work — various in beauty — various in power. Colour is, therefore, in brief terms, the type of love. [7.418-19]

Apollo and Python becomes for Ruskin the expression of the theme which more and more comes to dominate his writing. Everywhere he sees evidence of an archetypal conflict, of light against dark, of life against death, of love against sin. Looking at the picture, we can see what led him to that conclusion. The dragon-serpent writhes into the dark diagonal filling one-third of the frame, its wound and one claw along the edge of the dynamic axis that leads straight to the young Apollo, half kneeling in a pool of light, with a penumbra that is nearly a halo around his head. Behind him, on a secondary axis, the gentler curves that sweep upwards from the foliage on the left lead towards a quieter landscape. But the line of the distant ridge of mountains is carried diagonally back into the centre of the picture by the branch that the serpent has smashed. That is my own description. Ruskin concentrates on the moral meaning. ‘This is the treasure-destroyer, — where moth and rust doth corrupt — the worm of eternal decay. Apollo’s contest with him is the strife of purity with pollution; of life with forgetfulness; of love, with the grave’ (7.420). [84/117]

I have tried to show that Ruskin’s symbolic interpretations consistently carry both particular and universal significance; but these symbols do not just operate externally in works of art. They also have continuity on the psychological level. Ruskin could not have made his meaning more plain when he concluded of Turner, ‘his work was the true image of his own mind.’ But what is true of the artist Turner is also true of the critic Ruskin. On the very same page as his application of the symbolism of the Apollo to Turner’s life, he writes of himself: ‘Once I could speak joyfully about beautiful things, thinking to be understood; — now I cannot any more; for it seems to me that no one regards them’ (7.422). Again we must ask the question raised by the pathetic fallacy — are all these symbols no more than a projection of Ruskin’s increasingly unhappy mind?

It is clear that these and other symbols that emerge do have a psychological reference for Ruskin. They are not arbitrarily chosen, but come from the deepest recesses of his mind. However, having said that, I think this should be treated only as adding a further level of understanding. If we do this, we are presented with not only psychological insights, but a superbly coherent structure of imaginative imagery, a structure of imagery that is not limited to a single creative medium, like painting or poetry, but can be applied to any issue confronting the human mind; to history, to philosophy and, as we shall see, to economics. Anything, indeed, in indivisible reality. In an obscure footnote to an obscure article, Ruskin wrote: ‘It is a strange habit of wise humanity to speak in enigmas only, so that the highest truths and usefullest laws must be hunted for through whole picture-galleries of dreams which to the vulgar seem dreams only’ (17.208). We may read Ruskin’s enigmas as psychological evidence only, but if we do so, we will lose sight of the truths and laws which they conceal.

Ruskin's treatment of myth represents his final theory of the imagination, a theory which comprehends the three orders of truth of Modern Painters: the truth of natural fact, the truth of thought, both as impression and expression, and the transcendental truth of symbol. If we wish to add a further level of psychological truth, it can be done without distortion to the scheme. The imagination both perceived truth, and recreated it, so that as Ruskin evolved a theory of symbolism to help him interpret art, he began to apply it in his own writing, to the extent that his later work only becomes comprehensible when we see that he is operating a system of symbols expressed by natural fact.

Ruskin first applied the orders of truth to Turner in Modern Painters 1: [117/118]

in different stages of [Turner’s] struggle, sometimes one order of truth, sometimes another, has been aimed at or omitted. But from the beginning of his career, he never sacrificed a greater truth to a less. As he advanced, the previous knowledge or attainment was absorbed in what succeeded, or abandoned only if incompatible, and never abandoned without a gain; and his last works presented the sum and perfection of his accumulated knowledge, delivered with the impatience and passion of one who feels too much, and knows too much, and has too little time to say it in, to pause for expression, or ponder over his syllables. There was in them the obscurity, but the truth, of prophecy; the instinctive and burning language which would express less if it uttered more, which is indistinct only by its fulness, and dark with abundant meaning. [3.611]

This is a prophetic description of Ruskin’s own future development.

Last modified 2 September 2014