he firm has a complicated history. John Blackie, the founder, born in Glasgow in 1781, was sent out to work in the tobacco trade at the age of six, but as that business, which had been booming in Glasgow in previous decades, had slumped as a result of the American war, the young Blackie shifted, at age eleven, to the seemingly more promising handloom weaver’s trade. Perhaps because the weavers’ trade in turn came under threat, in this case from mechanisation, John Blackie left it in 1805, after his marriage and the birth of his first son John, and found employment with a company of booksellers, A. and W. D. Brownlie. Bookselling in the Scottish countryside at that time often took the form of soliciting subscriptions for books and delivering them in parts. “Except in the larger towns, bookshops were rare – almost unknown – in 1800,” Agnes A.C. Blackie explains in her book on the company, published in 1959. “In the country and the smaller towns people were largely dependent on the issue of books in paper bound sections called Numbers, sold by subscription, and delivered to subscribers section by section. As the sections were moderately priced, and could be paid for one by one, the Numbers trade also served to put books within the financial reach of relatively poor people” (Blackie, p. 3. See also W.G. Blackie, pp. 8, 13-14). John Blackie’s job with the Brownlies was to travel far and wide across Scotland and Northern England, seeking new subscribers and delivering the sections or numbers to existing ones. The lesson was not lost on him as he himself moved into bookselling and then publishing – the two trades being still closely connected, with booksellers themselves, in Scotland especially, and in Glasgow as well as Edinburgh, having reprints made of classic and popular works. According to The Edinburgh History of the Book in Scotland, the generally underestimated Glasgow publishing trade produced about one third of all books published in mid-eighteenth-century Scotland and around 25% or slightly higher through 1797 (II, 16-18). The advantage of Edinburgh’s publishing firms “essentially derived from its monopoly on legal and official printing” (II, 15).

John Blackie — a calotype print by David Octavius Hill and Robert Adamson. Courtesy of the Scottish National Portrait Gallery. Click on image to enlarge it.

Around 1808, the Brownlies arranged for John Blackie to take over their business, which had run into financial difficulty, and the following year Blackie took in as partners two friends, both of whom had also worked for the Brownlies. Besides selling books, the new firm, known as W. Sommerville, A. Fullarton, and J. Blackie & Co., began to publish its own books – notably religion-inspired texts such as Fleetwood’s Life of Christ and Thomson’s Travels in the Holy Land. Over the next two decades, the firm split up into a publishing-and-bookselling branch and a bookselling-only branch until in 1831, five years after John Blackie Jr., Blackie’s oldest son, had become a partner in the publishing company, the latter was re-established as Blackie & Son, and was totally in the hands of the Blackie family. The Blackie firm sought to reach out to a wide readership and was a pioneer in the production of inexpensive series. Another five years later, Blackie’s second son, William Graham Blackie -- who, besides having been trained as a printer, had attended the University of Glasgow and obtained a doctorate at the University of Jena in Germany, and who had taken over the running of the Valleyfield Printing Works in Glasgow, purchased by his father some time before and renamed W.G. Blackie & Co. -- was made a partner in his father’s firm, to be joined shortly after, in what was now very much a family affair, by John Blackie’s youngest son, Robert, who had a keen interest in book illustration and art and who had studied under Ingres in Paris (Blackie, p. 21). At a somewhat later date Robert’s son also joined the firm. By 1842, John Senior had withdrawn into the background, leaving his three sons — John Jr., William Graham, and Robert — virtually in charge of the company. The two still independent firms of Blackie & Son (the publishing house) and W.G. Blackie & Co. (the printer) amalgamated in 1890 as Blackie & Sons, Ltd.

Left three: Title-page and two pages from The Steam Engine: A Treatise on Steam Engines and Boilers (1891) . Right: Title-page and a page on a city in Hindustan from The Imperial Gazetteer (1856). These five images come from Internet Archive versions of books in the University of California Library. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

For many years Blackie published technical and practical works appropriate to the burgeoning industrial economy of Glasgow (The Engineer and Machinist’s Assistant [1843], Machinery and Mill Work [1848], Railway Machinery [1851], The Engineer and Machinist’s Drawing Book [1860], Steam Engines: A Treatise on Steam Engines and Boilers [1891]), reference works (The Imperial Dictionary [1847-50], The Imperial Gazeteer [1855], The Imperial Atlas [1859], The Popular Encyclopaedia [1841], a seven-volume reprint of the late 1820s American version of the Brockhaus Konversationslexikon; religious books (Thomas Haweis’ Evangelical Expositor [1818] in three volumes, of which several editions for family use were published in 65 to 168 “numbers” ranging in price from sixpence to a shilling each, and of which over 14,000 copies were sold, The Imperial Family Bible [1841], The Imperial Bible Dictionary [1863]); and the occasional fictional classic with a religious resonance (Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress [1820-1823], Richardson’s Pamela, or Virtue Rewarded [1820-1823]). Scottish writers were represented (James Hogg’s Poetical Works [1838-40], Robert Burns Poetical Works [1838-40]), as were some classics of historiography (Charles Rollin’s Ancient History [1826], Leopold von Ranke’s Popes of Rome [1846-47]). All, save the Encyclopaedia, were issued in “numbers,” at relatively modest prices. (Sketch, pp. 13-24).

From early on, however, the firm also engaged in publishing selections from the works of ancient, modern, and even contemporary literary writers – though, as might be expected, not all in the latter category are still read today. These were clearly designed to meet the needs of a modestly educated but expanding reading public. Books, Blackie held, were “instruments of enlightenment” (Blackie, p. 8). At the suggestion of John Blackie Jr., who had had a more formal education than the senior partners in the firm and who had strong literary interests, Blackie, Fullarton and Co. of Glasgow and A. Fullarton and Co, booksellers of Edinburgh, came together as early as 1828 to publish a two-volume duodecimo Casquet of Literary Gems of about 400 double-column pages each, described in the Preface reassuringly as “a collection of pieces of unequivocal merit and unobjectionable tendency, selected in some cases from rare old writers, but principally from the distinguished authors of the present day.” While some of the authors remained unidentified or have since been largely forgotten, the contributors included many celebrated names: among them, in the first volume alone, the Scottish poetess Joanna Baillie, Lord Byron, Thomas Campbell, John Clare, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, William Cowper, the sixteenth and seventeenth-century Scottish poets William Drummond of Hawthornden and William Dunbar, John Dryden, John Galt, William Hazlitt, Robert Herrick, Thomas Heywood, Thomas Hood, David Hume, Leigh Hunt, Washington Irving, Joseph D’Israeli, John Keats, Charles Lamb, Andrew Marvel, Charles Maturin, and John Milton. The collection was edited by one Alex Whitelaw, whom Blackie later employed again to prepare a 4-volume “continuation of the Casquet of Literary Gems,” entitled The Republic of Letters (1832) and, a few years later, A Book of Scottish Song (1843) and The Book of Scottish Ballads (1845). Enhanced by illustrations based on the work of David Scott, a notable Scottish painter of the time, the relatively inexpensive Casquet of Literary Gems went through several new and expanded editions and continued to be published into the 1870s and 1880s. The later editions were available, still in two volumes, in duodecimo format for seventeen shillings, or in five, in still smaller 48mo format for twelve shillings and sixpence. The range of writers was further extended in these later selections to include still more standard writers (James Boswell, Geoffrey Chaucer, William Congreve, Daniel Defoe, Edmund Spenser, Laurence Sterne, Jonathan Swift), a fair number of writers still living or only recently deceased (George Borrow, Samuel Butler, Charles Dickens, Charles Kingsley, Sir Edward Bulwer Lytton, Coventry Patmore, Algernon Charles Swinburne, Alfred Tennyson, Anthony Trollope) and several contemporary Americans (Louisa May Alcott, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow) along with a sprinkling of writers in translation, ancient, modern, and still living (Plato, Dante, Miguel de Cervantes, Victor Hugo, Ivan Turgenev).

A Selection of title-pages of books from the firm’s inexpensive popular editions. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

The Blackies continued the policy of publishing inexpensive popular editions of works of recognized literary merit right into the twentieth century: “Blackie’s English Classics” (early 1890s to 1910) with individual volumes devoted to Francis Bacon, Robert Browning, Oliver Goldsmith, Thomas Gray, Longfellow, Milton, Alexander Pope, Spenser, and Tennyson among others; the expanded Casquet of Literature: A Selection in Poetry and Prose from the Works of the Most Admired Authors, 6 vols. 1874; The Casquet Library of English Pastorals, 1895; The Casquet Library of Lyric Poetry (1500-1700), 1897; The Casquet Library of English Satire, 1906. Many texts from these collections were later re-edited and reissued in the so-called Warwick Library of English Literature; Blackie’s English Texts; Blackie’s Latin Texts; Blackie’s Longer French Texts; The Wallet Library (featuring a wide range of works by – among others -- Bacon, William Blake, Byron, Thomas Carlyle, Coleridge, Thomas De Quincey, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Hazlitt, Herrick, Lamb, Walter Savage Landor, Michel de Montaigne, Milton, John Ruskin, and Henry David Thoreau, along with Thomas More’s Utopia, and St. Augustine’s Confessions), etc. In addition, responding to the Education Acts of 1870 and 1872, which made education compulsory from age 5 to age 13, the company put out many series, both entertaining and instructive, designed especially with the education of the young in mind and as “rewards” for “punctual attendance” or “good work and conduct.” Blackie’s School and Home Library, renamed The Library of Famous Books, featured works not only by well-known authors of children’s books – Louisa May Alcott, R. M. Ballantyne, Lewis Carroll, Susan Coolidge, Anna Sewell – but by standard authors, such as Bunyan, Dickens, Goldsmith, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Sir Walter Scott, Swift, and Robert Louis Stevenson. The company issued catalogues devoted to “Books for younger children and primary school libraries” or “Educational Works specially adapted for elementary and higher schools” (1885).

Blackie, which established an office in London in 1837, and branches in India, Australia, Canada, and for a time New York, thus did a great deal to make the classics of English literature and some foreign language classics, as well as a fair number of contemporary works, easily accessible to a broad general public. In this respect the company was certainly following the traditional Scottish objective of education for all -- spreading the word -- as another Glasgow publisher, Collins, and the Edinburgh publisher Thomas Nelson also did, while at the same time pursuing the no less characteristic Scottish goal of legitimate financial profit (Finkelstein, pp. 116-19). The company motto, “Lucem libris disseminamus,” was entirely appropriate. None of the Blackies seems, however, to have sought out or entertained close social relations with writers, as Constable, Murray, Macmillan, Strahan, and George Murray Smith of Smith, Elder and Co. did, or to have been sought out by them, though the company did use the services of living writers to introduce the works of standard authors (e.g. the novelist George Gissing for the 1901-2 fifteen-volume “Imperial Edition” of the Works of Charles Dickens, or the poet Alice Meynell for many of the Blackie Red Letter poets).

Hillhouse. Designer: Charles Rennie Mackintosh. 1903. Click on image to enlarge it.

In one respect in particular, however, the firm was a remarkable and admirable innovator. In 1893 Talwin Morris was hired as Art Director and chief book designer – making Blackie perhaps the first publisher to employ a truly gifted and already fairly well known artist in such a capacity. Talwin Morris quickly established contact with the artists of the lively, avant-garde Glasgow School and, in particular, with Charles Rennie Mackintosh, whom he introduced to Walter Blackie in 1902, thus preparing the way for Blackie’s commissioning Mackintosh to design a house for him – the stunningly beautiful Hill House (now the property of the National Trust for Scotland), just outside Helensburgh, a resort town about twenty miles down the Clyde from Glasgow.

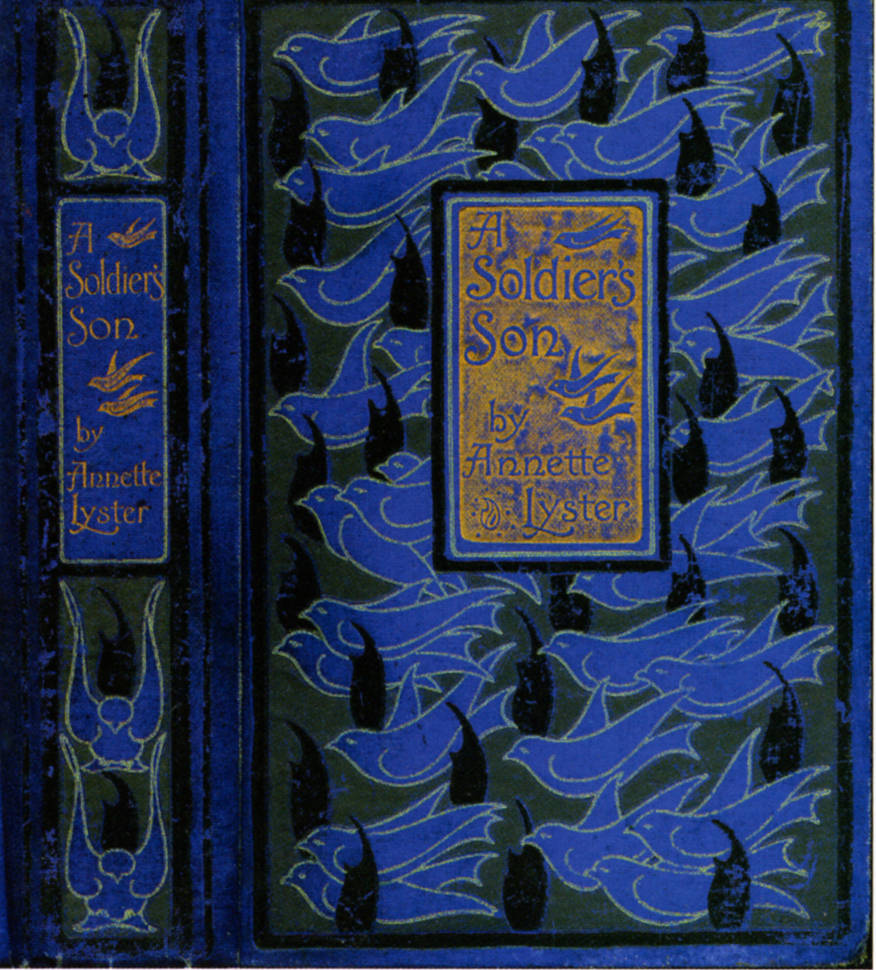

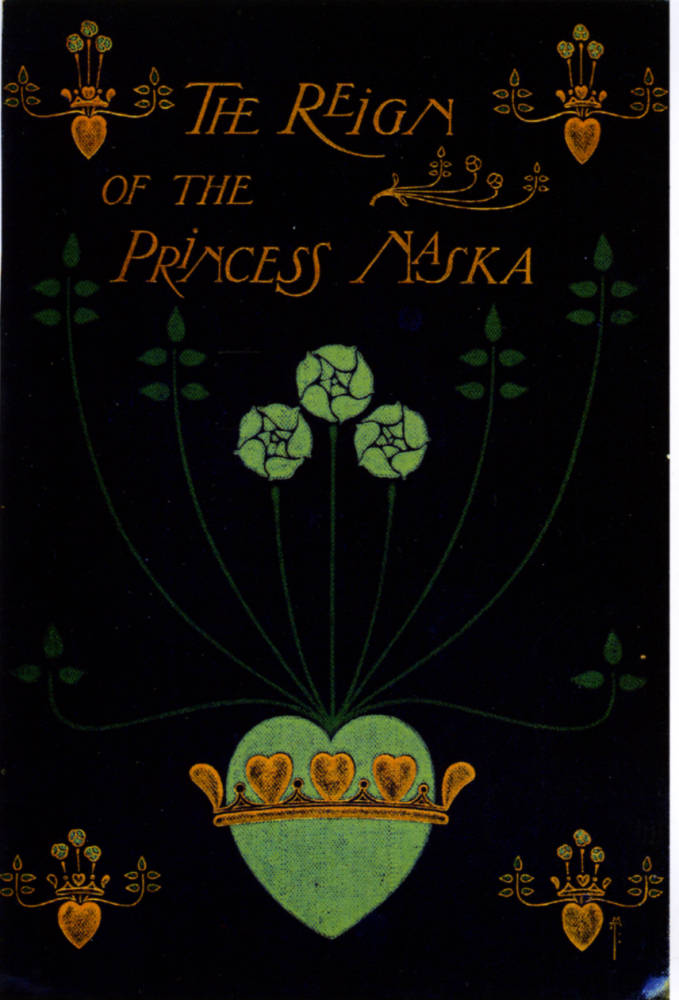

Four of Talwin Morris’s bookcover designs for Blackie & Co. and Gresham Publishing: Left: Mary C. Debenham's The Whispering Winds (1895). Middle left: Shakspeare’s Henry the Fifth (1898) . Middle right: R. P. Scott and Keith T. Wallas’s The Call of the Homeland (n.d.). Right: Amelia Hutchinson’s The Reign of the Princess Naska. (1899). [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Great distinction was brought to Blackie’s publications at this time by Talwin Morris’s striking art nouveau designs for the bindings, title pages, and endpapers of many of the firm’s products, including such practical or technical works as Modern House Construction (1898), The Modern Carpenter and Joiner (1902), The Horse: Its Treatment in Health and Disease (1906), The Modern Baker, Confectioner and Caterer (1907), or Modern Power Generators (1908). The firm also published to children’s books (The Crown Series of works by Harriet Beecher Stowe and Fennimore Cooper, among others; Stories Old and New, a series intended for children between the ages of 6 and 8 and 7 and 9 and including works by the brothers Grimm, Hawthorne, Defoe, and Swift; Little French Classics with short works by Alexandre Dumas, Alphonse de Lamartine, Prosper Mérimée, and Alfred de Vigny, as well as a volume of poems); books for older schoolchildren (Longer French Texts, with volumes devoted to François-René de Chateaubriand, Charles Baudelaire and Charles Nodier; a French Plays Series, with works by Molière, Eugène Labiche, and others; Little German Classics, with Heinrich Heine’s Harzreise and Friedrich Schiller’s Der Neffe als Onkel; The Plain-Text Poets with “Shorter Poems” by Milton and Longfellow’s The Song of Hiawatha. The Sixpenny Classics and the popular and modestly priced Red Letter series, directed toward a larger reading public and including the Red Letter Shakespeare, and the Red Letter Poets. Each volume of the latter was devoted to the work of a major poet, such as Matthew Arnold, Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Robert Browning, Longfellow, Christina Rossetti, Shelley, or Tennyson.

Spreading the Word: Scottish Publishers and English Literature 1750-1900

- Scotland and the Modern World: Literacy and Libraries

- Scottish Publishers, London Booksellers, and Copyright Law

- Andrew Millar (London) 1728

- William Strahan (London) 1738

- Robert and Andrew Foulis, The Foulis Press (Glasgow) 1741

- John Murray (London) 1768

- Bell & Bradfute (Edinburgh) 1778

- Archibald Constable (Edinburgh) 1798

- Thomas Nelson and Sons (Edinburgh) 1798

- John Ballantyne (Edinburgh) 1808

- William Blackwood (Edinburgh) 1810

- Smith, Elder & Co. (London) 1816

- William Collins (Glasgow) 1819

- Blackie and Son (Glasgow) 1831

- W.& R. Chambers (Edinburgh) 1832

- Macmillan (Cambridge and London) 1843

- Lesser Publishers

- Eighteenth- and Nineteenth-century British Copyright Law: A Bibliography

Bibliography

Blackie, Agnes A. C. Blackie & Son 1809-1959. London and Glasgow: Blackie & Son Limited, n.d. [1959]. [Cited in the text above as “Blackie.”

Blackie, W.G. Ph.D, LL.D. Sketch of the Origin and Progress of the Firm of Blackie & Son, Publishers, Glasgow, from its Foundation in 1809 to the demise of its founder in 1874 Printed for private circulation, 1897. This book has a beautiful cover design by Talwin Morris.

Cinamon, Gerald. “Talwin Morris, Blackie and the Glasgow Style.” The Private Library. 3rd series. 10.1 (Spring, 1987): pp. 3-47.

Buchanan, W. “Talwin Morris, Blackie and the Glasgow Style.” The Charles Rennie Mackintosh Society Journal 87 (2004): 10.

Cinamon, G. Talwin Morris and the Glasgow Style: Part II. The Charles Rennie Mackintosh Society Newsletter 29 (1981): 8–10.

Last modified 26 September 2018