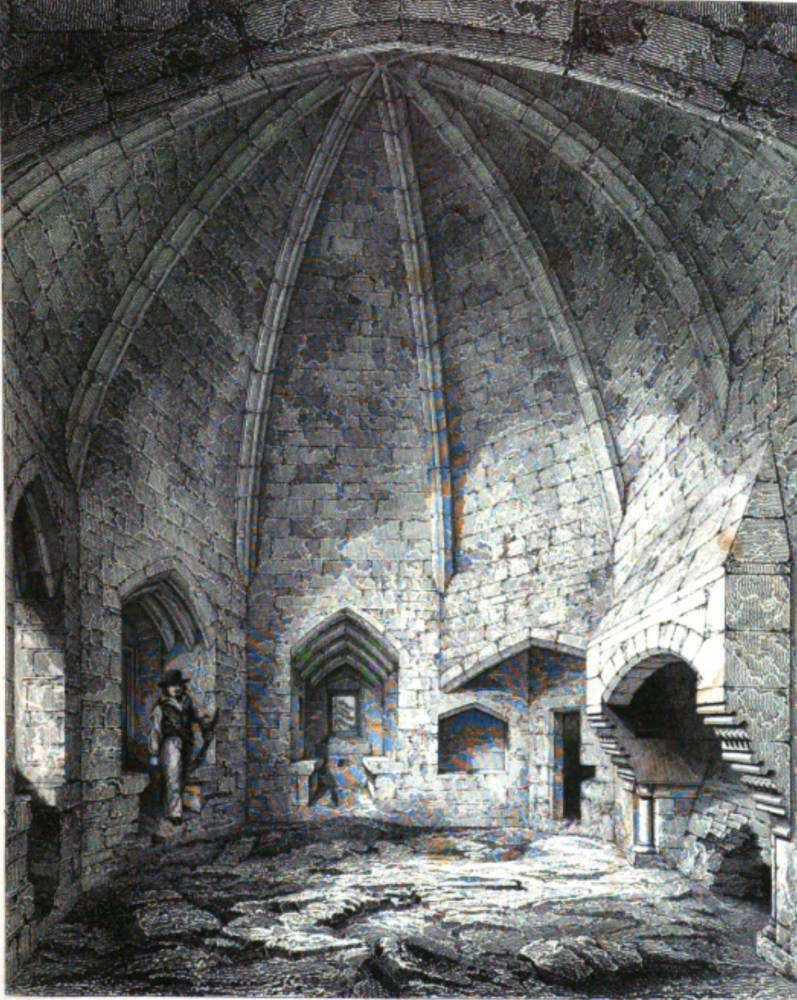

Dirleton Castle drawn by Robert William Billings (1814-1874) and engraved by J. Jeffrey. Source: Edinburgh (1852). [Click on image to enlarge it.]

Commentary by the Artist

THE vast ruins of this castle rise from what at a distance seems a gentle elevation, but, on a near approach, is seen to be a sharp perpendicular rock, though of no great height. It is surrounded by а considerable stretch of garden and pleasure ground, kept in punctilious order. Mixed with some ancient trees, the taste of the proprietor has attended to the preservation of a few of the more peculiar and uncommon vestiges of ancient gardening-thick, hard hedges of prevet and yew, impervious as green walls, with here and there bushes clipped into artificial forms. Exhibited in a succession of formal terraces, or on a continuous flat plain, this species of gardening often becomes intolerable. But round the gloomy ruins of Dirleton, and in immediate connexion with a forestlike assemblage of venerable trees, all feeling of hard, flat uniformity is lost, and the very stiffness and angularity of the outlines afford a not unpleasant contrast with the rest ofthe scene.

The original plan ofthe edifice appears to have been nearly a square. The side towards the south-east, which, rising from the less abrupt side of the rock, had little protection from nature, is a continuous wall of great height, with scarce a shot-hole to break its massive uniformity. At its southern extremity stands a round tower, and, a narrow curtain intervening, another stands farther towards the north. They spring from a broad base, their circumference narrowing in a parabolic curve as they rise, according to the idea which Smeaton is said to have taken from the stem of the oak. In the curtain there is a lofty external pointed arch ; within it, as in a recess, between two square towers, there is a gateway, which appears to have been the principal entrance of the castle. On the top, between the outer and the inner arch, there is a circular hole, made apparently to enable the garrison to assault any enemy that might have penetrated so far towards the interior. Opposite to this gateway there are the vestiges of a ditch; and four square solid pieces of building, little wider than pillars, appear to be the remains of the edifices connected with a drawbridge.

Both drawn by Robert William Billings. The left engraved by G. B. Smith and that on the right by R. Bransten. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

The greater proportion of the interior of the building yet remaining consists of vaults. Of the portions above the level of the rock, a few turnpike stairs and small chambers, in the intricacies of the masonry between the larger apartments, only remain. The hall, which seems to have been of great size, is rooñess, and covered with thick grass. At its extremity is to be found the only piece of ornament, unless, perhaps, a slender moulding, which the edifice supplies,-the canopied seat represented in thc subjoined cut, which yet would hardly be deemed worthy of admiration, if it were found in an ecclesiastical instead of a baronial building.

This fair lordship was one of the possessions of the horde of Norman barons who occupied so large a portion of the fruitful Lothians before the war of independence; and the name of its earlier owners, De Vallibus, or De Vaux, at once bespeaks a race who, after the conflict, ceased to be connected with Scotland, and gave way to such families as its subsequent owners, the Ruthvens and Nisbets. In 1298, when Wallace was falling back before the advancing arms of Edward, this castle was strong enough to maintain a Scottish garrison in the very centre of that southern district, which in other respects had yielded to the conqueror's arms. The garrison made frequent sallies and attacks on the English troops; and Edward, who was encampcd afew miles west of Edinburgh, sent his warlike bishop, Anthony Beck, to lay regular siege to the fortress. It offered a protracted resistance, and surrendered on terms [Tytler's Hist., i. 160]. When the English were driven from Scotland, it became one of the possessions of the house of Haliburton, which, according to Sir Walter Scott, who was himself descended from it, “made a great figure in Border history, and founded several families of high conscquence” (Ргоsе Works. 406.). In later times, Dirleton belonged to the unruly and unfortunate family of Ruthven. It would appear that Logan of Restalrig had some claim ou its possession, and that the admission of this claim was the bribe by which that conspirator, owner of the neighbouring wild sea-tower of Fastcastle, agreed to assist in the Gowrie conspiracy; for he says in one of his letters to his Confederate, Laird Bower,

I hev recevit ane new letter fra my lord of Gowrie, concerning the purpose that Mr Аl[exander], his lo[rdship’s] brothir, spak to me befoir; and I perseif I may hev advantage of Dirleton, in case his other matter tak effect, as we hope it sall. . . . I cair nocht for all the land I hev in this kingdome, in case I get a grip of Dirleton, for I esteem it the pleasantest dwelling in Scotland" [Pitcairn’s Criminal Trials, ii. 283]

— an opinion by no means discreditable to the conspirator’s taste for rural scenery.

In the middle of the seventeenth century, a revolting scene, unfortunately too characteristic of the age, appears to have occurred within these Walls. A man named Watson, and his wife, long suspected, as the record tells us, of witchcraft, hearing that John Kincaid “wes in the toune of Dirletoue, and had some skill and dexteritic in trying the divellis marke in the personis of such as wer suspect to be witches,” voluntarily offered their persons for trial of his skill, and were examined in the “broad hall ” of the castle of Dirleton. If the poor people, trusting in their innocence, believed that no indication of the unhallowed compact would be found on their persons, they were lamentably deceived ; for Mr Kincaid, being а skilful man, succeeded in finding a spot in each, which he could pierce without producing sensation, or any issue of blood. One of those events, so incomprehensible in the early witch-trials, followed-a confession of strange and ludicrous intercourse with the enemy of mankind. Mrs Watson confessed that he appeared to her first in the Shape of а physician, who prescribed for her daughter, and received a fee of two English shillings. He seems to have behaved much like an ordinary individual, for “She gave him milk and bread; and, Patrick Watson coming in, she sont for а pynt of ale.” These statements were authenticated on 1st July 1647, but the fate of the confessing witch is not recorded.[Ibid., 599.]

The castle and the surrounding territory are at present the property of Mrs Hamilton Nisbet Ferguson.

R. W. B.

[These images may be used without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose without prior permission as long as you credit the Hathitrust Digital Archive and the University of California library and link to the the Victorian Web in a web document or cite it in a print one — George P. Landow ]

Bibliography

The Baronial and Ecclesiastical Antiquities of Scotland illustrated by Robert William Billings, architect, in four volumes.. Edinburgh and London: William Blackwood and Son, 1852. Hathitrust Digital Archive version of a copy in the University of California Library. Web. 10 October 2018.

Last modified 11 October 2018