The following account is based largely on the introduction to the exhibition held at the Hartlepool Art Gallery on the 150th Anniversary of James Clark's birth. The exhibition ran from 19 April-1 June, 2008. Many thanks to Charlotte Taylor, who curated the exhibition and sent in material about Clark. Thanks also to Richard McGrath, who corrected one of the dates here. — Jacqueline Banerjee

Introduction

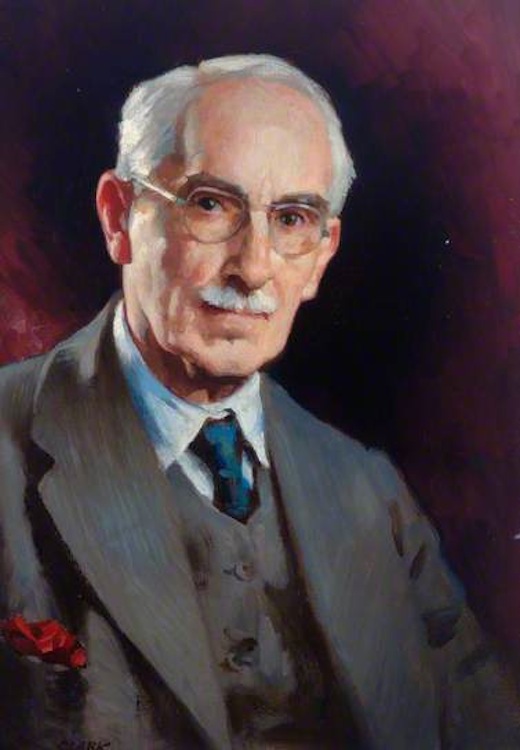

The artist James Clark (1858–1943) was born in West Hartlepool, not far from Middlesborough and Stockton-on-Tees in north-east England. His paternal grandfather was from Lanarkshire, but his father William had come to work in the shipbuilding trade in Hartlepool, and later, after a spell in South Africa, had set up as a pawnbroker in Hartlepool again. James, his eldest son, first trained as an architect, entering the office of the prominent local architect James Garry when he was just twelve years old. Indeed, it was James Clark himself who designed the family home, Sunnyside, in Stockton Road. But his father had paid for him to have watercolour painting lessons as well, and in 1875 the young man gave up his architectural career for life as an artist, moving to London in 1877.

In London, having diligently practised drawing in the British Museum, Clark won a scholarship for full-time study at the National Art Training School, finishing his training in Paris, eventually in the Ecole des Beaux Arts. There he studied under Léon Bonnat, and, as his Times obituary would later report, was one of a group of avant-garde artists at that time. After his return, by then married to his childhood sweetheart Elizabeth, he spent most of the rest of his life in London. He exhibited regularly at the Royal Academy, and became an art examiner for the Board of Education and Cambridge University — again, these details appear in his Times obituary (p.6). In 1886 he painted one of his best-known works, Magnificat, which is in the collection of Sunderland Museum. This is appropriate: he never lost touch with his northern roots. For example, he visited Hartlepool after its terrible Bombardment by the German navy in December 1914, in order to memorialise the devastation in his painting. After that, feeling the "lure of the Orient" like so many of his earlier contemporaries, he traveled to Palestine to research the landscape and people there for his paintings of religious subjects.

Clark's work in different media included wall paintings at Holy Trinity, Casterton, Cumbria, between 1905 and 1912. But it was in 1914 that he really rose to fame, with a painting entitled The Great Sacrifice. This was reproduced in a special issue of the Graphic as part of its Christmas number, and its idealised representation of a dead soldier at the foot of the cross became a popular print and was used as a war memorial in many public buildings, and as the source of stained-glass memorial windows in a number of churches. It seems indeed to have been "the most popular painting of the war," with its religious imagery providing "consolation to the families of dead soldiers" (Robb 163). The original went to the royal family: in January 1915, King George bought it, under its later title Duty, at the War Relief Exhibition at the Royal Academy (see "The King at the Academy"). But Clark produced other copies, and other paintings on the theme of war. He designed other war memorials, too. When his health deteriorated, he and Elizabeth moved to moved to Reigate in Surrey, and that is where he died in 1943.

Clark was still a well-known name then. Although the Times described him simply as a "painter of subject-pictures and water-colours" in a brief obituary on 16 January that year (p. 4), it ran a rather longer obituary just two pages later, giving some details of his biographical background, reminding readers of his famous war painting, pointing out his versatility in also painting murals and designing stained glass, and adding that "he invariably displayed painter-like qualities of a high order." Clark would mainly be remembered, suggested the obituary, "for the essentially English water-colours which he painted with much skill and a delightful sense of colour and movement." The obituary also noted that he was survived by his wife, and that of their three sons and three daughters, one had become a very distinguished Brigadier in the Royal Engineers.

Works

Additional Sources

Fox, James. British Art and the First World War, 1914-1924. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015.

"The King at the Academy: Purchases at War Relief Exhibition." The Times 6 January 1915: 10. Times Digital Archive. Online ed. Web. 8 July 2015.

"Mr James Clark." The Times 16 January 1943: 6. Times Digital Archive. Online ed. Web. 8 July 2015.

"Obituary." The Times 16 January 1943: 4. Times Digital Archive. Online ed. Web. 8 July 2015.

Robb, George. British Culture and the First World War. Basingstoke: Macmillan, 2015.

Westcott, Karen. "Work of North-East Artist on Show." The Northern Echo. 19 April 2008. Web. 8 July 2015.

Last modified 6 January 2023