The inspiration for an exhibition of contemporary British art that would tour America was that of an American, Augustus Ruxton. In his reminiscences William Michael Rossetti writes:

In 1856 a gentleman not as yet in any wise known to me, Captain Augustus A. Ruxton, an officer who had retired from the army still youthful, conceived a project of getting up an exhibition of British paintings in America – New York, and if convenient some other cities ... Captain Ruxton had no sort of connexion with fine art or its professors; but he felt a liking for pictures, and, having all his time to himself, and a wish to come forward in any way which might ultimately promote his fortunes, he partially matured this American project in his own mind, and then looked out for some one to act as secretary, and to serve as medium of communication with artists. He wishes more particularly to secure those of the Preraphaelite quality. Owing to my recent connexion with the American art-journal The Crayon, he fixed upon me; I had various interviews with him, and I assented to his proposal, with a modicum of salary annexed ... When Captain Ruxton’s American project had obtained some degree of publicity, it turned out that Mr. Ernest Gambart, then the most prominent and resourceful picture-dealer in London, had also been entertaining a plan of like kind. Some uncertainties ensued; and finally it was arranged that Gambart should combine his scheme with ours – he being far the stronger in watercolours, while the great majority of the oil-pictures came through our agency ... Ruxton obtained through me an introduction to Madox Brown; and at one time it was proposed that Brown should accompany the works across the Atlantic, but this came to nothing. [264-265]

Originally Ruxton was considering George Scharf, the man who was to organize the Art Treasures Exhibition in Manchester in 1857, for the post of secretary but Thomas Woolner convinced him that W. M. Rossetti was the right man to consult (Peattie, Letters, 83).

Examples from the variety of works selected. Left to right: (a) The Light of the World by Ford Madox Brown, 1853-55. (b) Glacier at Rosenlaui by John Brett, 1856 (c) "For Only One Short Hour" often referred to as The Seamstress and A Song of the Shirt by Anna Elizabeth Blunden, 1854.

Ruxton left for America at the beginning of May to select a suitable exhibition venue and to communicate with leading men there who might be prepared to support the venture. Prior to June Rossetti wrote a circular that was distributed to artists and to art periodicals in order to explain the scheme and to ask for their cooperation. Various periodicals responded, with most endorsing the basic premise, but expressing concerns about the feasibility of such an exhibition. On June 20, 1857 The Athenaeum announced plans for such a proposed American exhibition. This unexpected announcement caused art dealer Ernest Gambart to be extremely vexed because he had already been contemplating mounting an exhibition of British pictures in New York for some time. In a letter of July 5 to W. M. Rossetti, Gambart initially agreed to give up his own project but this decision did not last long. It appears there was indignation in the artistic community that British art was going to be largely represented abroad by a minority group of Pre-Raphaelite artists. After Gambart returned from a trip to Paris he wrote a subsequent letter to Rossetti on July 21:

I am so upbraided for giving up my Scheme of a New York English Exhibition by artists who seem to place their confidence in me & denounce your ability of gathering a genuine English collection and representing the British school, that I must, in justice to my friends, whom I seem to have deserted too easily, ask you what prospects you have of Succes [sic] & the names of the artists who have either given you or promised you Pictures, for if, as I am told on every side, you represent only a very small body of men & have no support of the academical body & the generality of artists, I would be guilty of gross neglect towards my friends, if by my withdrawal, I lent myself to the furtherance of the interests of a cottery [sic] to the exclusion of the generality.... Now, as I told you above my friends complain & deny you any authority to call yourselves the representatives; they denounce your utter inability in gathering an exhibition of the British school in works of art contributed by artists; they pretend your efforts will remain unsuccessful, & between your pretensions & my desertion that there will be either a very unsatisfactory exhibition or no exhibition at all. [Maas, Gambart, 91]

As can be seen Rossetti’s expression “some uncertainties ensued” was certainly an understatement of the facts! Fortunately a compromise was arrived at that allowed plans for the exhibition to continue. Gambart selected the watercolours for the show while Ford Madox Brown, assisted by the critic Tom Taylor and the noted Liverpool collector John Miller, selected the oils. Even here Gambart proved difficult, however. Madox Brown’s diary for January 17, 1858 records the following: "All this while the American exhibition had been going on. I was to have gone over to hang the pictures, however, the scoundrel Gambart put a stop to that, and all I had was the trouble to select the daubs" (Surtees, Diary, 199).

All works had to be sent in before the end of August 1857. The works were to be insured and exhibitors were relieved from all expenses of transportation. A moderate percentage would be charged upon the sale price of any works disposed. Contributing artists could determine whether any of their works which might remain unsold at the close of the exhibition in New York would be returned to them transport free, or whether they would be left to be shown in subsequent exhibitions. In June 1857 the Art Journal was still expressing doubts about the proposed show:

It is known that a plan has been for some time in progress for sending to the United States such a collection of British pictures as shall uphold and extend the reputation of our artists, and be otherwise advantageous to them, while it may have the effect of benefitting our brethren on the other side of the Atlantic by acting as a teacher. This project is admirable in theory, and we shall very cordially rejoice if we find it so carried out as to be really what it ought to be, and must be, to become practically useful. Our doubts arise from our belief that it is next to impossible to collect a sufficient number of high-class pictures to form an exhibition.... It will be a serious and fatal mistake to imagine that the Americans will be satisfied with mediocrity – they can distinguish excellence quite as well as we can; they have many liberal and judicious collectors, and several extensive collections, and especially their artists generally are entitled to take prominent rank. We shall not find it in England so very easy to over-match the more eminent of their painters. The experiment will, therefore, be a failure unless a large number of paintings of the highest merit be submitted to them.... We confess that our fears are stronger than our hopes. [294]

Two exhibits by female artists. Left: Clerk Saunders, a watercolour by Elizabeth Siddal. Right: Under Cliff (Ventnor, Isle of Wight), a watercolour by Barbara Bodichon.

The Art Journal, in a follow-up article in July, reported:

We alluded last month to the projected exhibition, in America, of the works of British artists; we have since then received a catalogue of the pictures which have been collected for the purpose: it contains a list of about 170 oil-paintings and nearly 180 watercolour drawings; but the committee have evidently found it, as we hinted they would, no easy matter to get together any number of works of the best order and by our best painters. Among the oil-pictures are examples of Anthony, Archer, Armitage, F. M. Brown, Burton, T. S. Cooper, Cross, F. Danby, Dillon, Gale, Gosling, F. Goodall, J. D. Harding, G. Harvey, G. E. Hering, J. C. Horsley, Hulme, Holman Hunt, Lance, Leighton, James Linnell, Lucy, Maclise, Oakes, H. W. Pickersgill, P. F. Poole, Redgrave, Sant. G. C. Stanfield, F. Stone, F. Taylor, E. M. Ward, Wingfield, &c., &c.; but with a few exceptions it seems very doubtful whether these pictures will offer to the American public an adequate idea of the powers of the respective painters. The water-colour artists are, we presume, better represented: the list includes very many of the leading men in both societies; and, inasmuch as drawings are more easily collected than large and important works in oil, the exhibition in this department bids fair to do credit to our school. [326]

By September Buxton and a Mr. Frodsham, a representative of Gambart, had arrived in the United States. Four sites had initially been selected for the exhibition – New York, Philadelphia, Boston and Washington D.C. No evidence exists, however, in terms of records and exhibition reviews to suggest the Washington exhibition actually occurred, although W. M. Rossetti mentions it in his Reminiscences as the venue where a violent rainstorm damaged several watercolours (266). This storm actually occurred in Boston, however, in August 1858 when pictures were enroute to the ship that was to bring them back to England. Ruxton was forced to pay out at least £1200 in compensation and losses to artists because of the damage.

A particularly popular exhibit: King Lear (Lear and Cordelia) by Ford Madox Brown, 1849-54.

The first exhibition opened in the new gallery of the National Academy of Design in New York on October 20 and ran until early December. A total of 356 works were included, 168 oil paintings and 188 watercolours. In the absence of Madox Brown, Ruxton was aided in the hanging by William James Stillman and John Brown Durand, editors of the prominent art journal The Crayon. Stillman complimented Ruxton on his hang: "His arrangements of the pictures with regard to hanging etc. has been the admiration of Artists and connoisseurs and is indeed most just and impartial. There is no artist whose works are hung who has any reason to find fault" (Peattie, Letters, letter 54n.5, 90). The exhibition in New York had the largest number and highest calibre of works of any of the venues. Some of the works by Arthur Hughes, for example, did not appear in any other city as did the five watercolours by Turner. As it turned out apprehension about the potential success of the exhibition proved all too true. The timing was poor since the opening coincided with one of the most desperate financial crisis in the stock market of the 19th century. The public, distracted by this catastrophe, had little interest in exhibitions, much less buying art. Initially the exhibition seemed to go well, however. Ruxton in his initial report to Rossetti wrote: "I have to announce a most successful opening of the Exhibition at the private view last night. All the leading people of the city were present – indeed the rooms were crammed, and the most cordial and kindly feeling was manifest.... The Light of the World creates a great sensation; but Madox Brown’s King Lear seems to be the most popular picture of the Exhibition" (Dickason, Daring Young Men, 67-68). To get some idea of attendance at the exhibition opening 68 dollars was raised from the sale of catalogues at 15 cents each. Not everyone shared Ruxton’s optimistic view of the exhibition, however, even some expected to be highly supportive. In a letter to W. M. Rossetti of November 17, 1857 W. J. Stillman writes:

The committee seem to have thought that things which were second-rate at home were fit to represent English art here, while in the main our amateurs are as well acquainted with English art as the English public itself. The feeling here was that the Exhibition was intended as an exposition of the attainment of English art; yet there are many pictures which the public feel were sent here in presumption of ignorance or bad taste on our part, and we are a sensitive people on such points.... The preraphaelite pictures have saved the Exhibition as far as oil pictures are concerned, but even they should have been culled more carefully. You should have thought that the eccentricities of the school were new to us, and left out such things as Hughes’s Fair Rosamund and April Love, The Invasion of the Saxons [by William Gale], with Miss Siddal’s Clerk Saunders, and The London Magdalene; all which may have their value to the initiated, but to us generally are childish and trifling. Then you have much neglected landscape, which to us is far more interesting than your history painting…There must be something vital and earnest in a picture to make it interesting to our public, - and any picture which has not that had better stay in England. The P.R.B. pictures have, I venture to say, attracted more admirers than all the others for this reason, and at the same time been more fully appreciated than they are at this day in England. [Rossetti, Ruskin: Rossetti, 188-8].

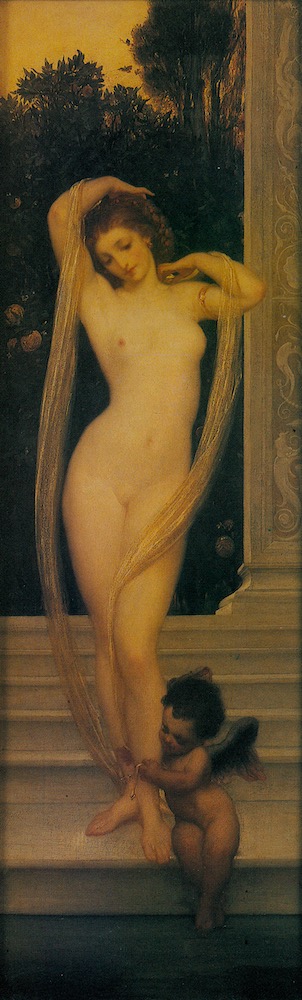

American critics were disappointed there were no oils on display by British artists like J. W. W. Turner, John Everett Millais, and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, whose work they had expected to be included and were especially looking out for. Turner at least was represented by watercolours. Millais wanted to participate but he had no finished appropriate work to send at that time. He had hoped to consign The Blind Girl but John Miller had already promised it to an exhibition in Liverpool. In addition to questions by Americans as to the quality of the art exhibited, concerns were also raised in New York about the nudity of two of Frederic Leighton’s works A Venus and Cupid and Pan. The paintings were “huddled out of sight by request, lest the modesty of New Yorkers should be alarmed” (Rossetti, Reminiscences, 266). When Leighton found out about this censorship he requested the paintings be returned to London. Although they are listed in the catalogue for the subsequent Philadelphia exhibition it is unlikely they were shown. The majority of the works exhibited were by conventional artists, and not by the Pre-Raphaelites, just as Gambart had wanted. Despite the limitations of the works displayed critics and visitors in general looked upon the exhibition favourably. On October 20, 1857 a critic for The New York Herald particularly commended the watercolours and remarked on the quality of the art in general that “not one of all this number is bad, few are indifferent, nearly all are very good, and many superb.” None of the critics for the various periodicals failed to notice the work of the Pre-Raphaelite artists, with some giving derogatory comments while other were complimentary. The exhibition unfortunately proved not to be a commercial success although there were some sales and a total of three thousand dollars was taken in.

Left: The Eve of St Agnes by William Holman Hunt, 1856-57. Right: Fair Rosamund by Arthur Hughes, 1854.

Following the completion of its New York run the exhibition moved on to Philadelphia at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts for the period February 3 – March 20, 1858. Gambart had opposed moving the exhibition on to Philadelphia and Boston and wanted it to close after New York. The venues in both Philadelphia and Boston generously offered to pay the expenses of the Exhibition to their cities and to set aside one thousand dollars to meet the costs of freight and insurance to send any unsold works back to England. With various omissions and replacements the number of pictures on display in Philadelphia was substantially reduced to 232 works, 105 oil paintings and 127 watercolours. Again the exhibition was not a financial success but in general it found favour with the critics. The Pennsylvania Inquirer, for instance, stated, “the surprising excellence of many of the specimens…so far exceeded our anticipation that they excited surprise as well as intense admiration” (2). The Pre-Raphaelite works again received their fair share of both praise and ridicule from various reviewers. The Sunday Dispatch reviled the Pre-Raphaelite paintings which were felt to be too rigid, false, and even too medieval and “Catholic” (Casteras, 1857-58 Exhibition, 115). This venue was much more favourable than New York for the sale of works of art with about 56 pictures selling. Leighton’s The Reconciliation of the Montagues and the Capulets sold for £400 to a Mr Harrison. A prominent New York collector John Wolfe bought Holman Hunt’s The Light of the World for £315 while Ford Madox Brown’s watercolour Looking Towards Hampstead sold to Ellis Yarnell for £30.10s. John Brett’s A Bank wheron the Wild Thyme Grows sold for £40 and R. B. Martineau’s The Spelling Lesson sold for £80.

The exhibition next moved to Boston to the Boston Athenaeum where it ran from April 5 – June 19, 1858. At this venue the total number of pictures rose to 321, including 104 oil paintings and 214 watercolours, because of additional forty pictures sent over by Rossetti. This venue also included three bronze medallions by Thomas Woolner that had not been shown elsewhere. There was again a mixed response to the Pre-Raphaelite works on display. A reviewer for The Crayon in its May 1858 issue commented, "although the exhibition is a decided success, I do not think the Bostonians take very kindly as yet to the works of the Pre-Raphaelite school" (148-149). After W. J. Stillman gave a public lecture in early May praising the Pre-Raphaelite works on display a letter to the editor of The Boston Daily Evening Transcript complained that the talk had bestowed "the laurel to the pretentious egotists of the so-called Pre-Raphaelites for turning from the puerile pursuit of beauty to the search for truth, be it ever so hideous or disgusting" (4).

Left: The controversial Venus and Cupid by Frederic Leighton, 1856. Right: Study of a Block of Gneiss (Fragment of the Alps) by John Ruskin, c.1854-56.

Despite the fact that Pre-Raphaelite pictures were in the minority at all the venues the exhibition travelled to, in all the cities critics focused primarily on Pre-Raphaelitism "as the most significant revelation of the exhibition, and they attributed its development almost totally to Ruskin’s influence" (Casteras, 1857-58 Exhibition, 119). Even though they were in the minority there was still a large presence of artists affiliated with the Pre-Raphaelites, many of whom had exhibited at The First Pre-Raphaelite Group Exhibition that was held at Russell Place in 1857, had been asked to join the Pre-Raphaelite sketching club The Folio, or would later become members of the Hogarth Club when it was founded in 1858. The best synopsis of the criticism of individual Pre-Raphaelite pictures is found in Casteras’s comprehensive article (116-130). The most significant Pre-Raphaelite contributors to the exhibitions in terms of numbers of works lent were Ford Madox Brown and Arthur Hughes. Brown lent six works in total, including two oil paintings, two watercolours, and two drawings. Only the small watercolour of Looking Towards Hampstead: from the Artist’s Window was sold during the tour and, to add insult to injury, his crayon drawing of Oure Ladye of Good Children and his painting of King Lear were damaged in transit from Boston in August 1858. Although King Lear proved popular with exhibition visitors and critics, its high price of $1000 deterred potential buyers. Although William Holman Hunt only lent two works, smaller versions of The Eve of St. Agnes and The Light of the World, the latter was the single Pre-Raphaelite painting that garnered the most attention from critics. The New York Times, for example, while it detested all the other Pre-Raphaelite pictures in the show greatly admired The Light of the World. The Philadelphia Sunday Dispatch, however, despised the picture and wrote scathingly of its faulty drawing, hard and unnatural colour, and its general tone of "moral blasphemy." Despite Stillman’s initial concerns Pre-Raphaelite landscape painting was actually well represented, including four works by John Brett, four by G. P. Boyce, two works by J. W. Inchbold, and two by William J. Webbe. Liverpool Pre-Raphaelite artists like William Davis, John William Oakes, Henry Mark Anthony, and James Campbell also exhibited landscapes. John Ruskin showed his watercolour Study of a Block of Gneiss, Valley of Chamouni, Switzerland, one of his most detailed geological studies. Female Pre-Raphaelite artists were included as well. Barbara Leigh Smith Bodichon exhibited eleven watercolour landscapes that were admired by William Michael Rossetti who called her "an amateur of great power" (Thirwell, William and Lucy, 133). Anna Blunden garnered praise from the critics for her social realist painting The Song of the Shirt, while Elizabeth Siddal’s Clerk Saunders was one of the works most ridiculed by hostile critics. Siddal withdrew the watercolour after the New York showing.

At the end of the exhibitions run Rossetti commented, "Ruxton was a loser by his spirited speculation – Gambart, I dare say, not a gainer" (Rossetti, Reminiscences, 266). Despite the fact that the American exhibitions of 1857-1858 did not prove to be a financial success, they did succeed in showing visitors, artists, and critics examples of modern English art, particularly by the Pre-Raphaelites. Although Pre-Raphaelite art proved controversial, with their works causing the most heated discussions in the American press, it was to exert on influence on contemporary American painters, particularly the landscapes the so-called “American Pre-Raphaelites” would later produce. As a critic for The Atlantic Monthly summarized: "Pre-Raphaelitism must take its position in the world as the beginning of a new Art, – new in motive, new in methods, and new in the forms it puts on…the only mistake men can make about it is to consider it as a mature expression of the spirit which animates it" (505). This speculation was to prove prophetic as the first phase of “hard-edged Ruskinian” Pre-Raphaelitism evolved into the second phase of Pre-Raphaelitism just at this time period.

Links to Related Material

- The Exhibition of Modern British Art in America, 1857-1858 (partial list of works shown)

- Pre-Raphaelite Sketching Clubs

- A List of Works Created at the Sketching Clubs Associated with Artists of the Pre-Raphaelite Circle

- The First Pre-Raphaelite Group Exhibition

- The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood

- The Hogarth Club

Bibliography

Casteras, Susan P. “The 1857-58 Exhibition of English Art in America and Critical Responses to Pre-Raphaelitism” in The New Path Ruskin and the American Pre-Raphaelites. Eds. Linda S. Ferber and William H. Gerdts. New York: Schocken Books Inc., 1985, 109-133.

Dickason, David Howard. “British Pre-Raphaelite Art in America: 1857 Exhibition.” Chapter 6 in The Daring Young Men The Story of the American Pre-Raphaelites. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1953, 65-70.

Maas, Jeremy. Gambart Prince of the Victorian Art World. London: Barrie & Jenkins Ltd., 1975, 94-97.

Rossetti, William Michael. Some Reminiscences of William Michael Rossetti. Volume 1. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1906, 264-268.

Rossetti, William Michael. Selected letters of William Michael Rossetti . Ed. Roger W. Peattie. University Park and London: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 1990, 86-91, 95-96, 98.

Rossetti, William Michael. Ruskin: Rossetti: Preraphaelitism Papers 1854 to 1862. London: George Allen, 1899, 178-182.

Surtees, Virginia. The Diary of Ford Madox Brown. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1981.

The Art Journal. “Art: England and America” and “Exhibition of English Art in America.” 1857, 294, 326.

The Atlantic Monthly. “The British Gallery in New York.” 1 (February 1858): 501-07.

The Boston Daily Evening Transcript. “Letter from T.T.S. to the Editor.” (May 11, 1858): 4.

The Crayon. “Sketchings.” 5 (May 1858): 148-149.

The New York Herald. “The Fine Arts in New York.” (October 20, 1857): 2.

The Pennsylvania Inquirer. “Amusements.” (February 3, 1858): 2.

Thirwell, Angela. William and Lucy The Other Rossettis. New Haven & London: Yale University Press, 2003, 131-35.

Last modified 14 December 2021