[This biography pf Prout comes from the Internet Archive version of a copy of Sketches by Samuel Prout, in France, Belgium, Germany, Italy and Switzerland (1915) in Cornell University Library (NC 242.P96A15). A monochrome version of the decorated initial “T” opens the originbal text. Click on images to enlarge them.]

HE true student and lover of architecture may admire a noble building of past centuries, he may note its agreeable proportions and the beauty of its details; but it is the glory of its age, its associations, its message from the past, and its quiet atmosphere of dignity and repose which will appeal to his imagination by giving to it an indefinable human attribute which responds to and satisfies his higher senses. The artist who sets himself to portray picturesque architecture, whether it be the simple beauty of a rustic cottage, a group of old houses in some medieval town, or the noble grandeur of a venerable cathedral, must possess something more than mere technical skill as a draughtsman or a fine sense of colour. He must bring to his task sympathy and reverence, a keen appreciation of the symbolic value of the ancient relics of the past, and a feeling for the sublime romance which hovers around old buildings. Be the outward forms rendered ever so faith- fully, the result will not satisfy unless the artist can give expression to those inherent qualities which are inseparable from his subject. The lack of ability to comprehend and to suggest these higher and more subtle elements is the reason why so many pictures of ancient archi- tecture are wanting in interest.

Amongst the few artists who have achieved fame as painters and delineators of picturesque architecture Samuel Prout holds a unique position, and his success was in no small measure due to the fact tnat his deep sympathy with, and delight in, his subject are manifest in his works, whether it be a delicate lead pencil drawing, a water-colour, or one of his better-known lithographs. In them are revealed those higher attributes to which we have just referred; and it is impossible to contemplate one of his characteristic works without feeling that here we have an artist who has successfully found for himself an ideal means of expression. The old towns of the Continent, with their picturesque houses, time-worn churches, and busy market-places, were a constant source of joy to him, and in the rendering of them he was uniivalled. His friend Ruskin, than whom Prout never had a greater admirer, in his Modern Painters, says: "His renderings of the character of old buildings, such as that spire of Calais, are as perfect and as heartfelt as I can conceive possible; nor do I suppose that anyone else will ever hereafter equal them." But before considering the various aspects of Prout's achievements in that particular phase of pictorial art in which he ultimately "found" himself, it is desirable that a brief account should be given of his earlier life, and an attempt made to trace the development of his art up to the time of his first visit to the Continent, in 1819, an event which was to have a far-reaching effect on his career. Born at Plymouth on the 17th September 1783, he was barely five years old when, wandering forth alone one hot day, armed with a hooked stick to gather nuts, he was found by a farmer towards evening lying under a hedge prostrated by sunstroke, and was brought home insensible. This unfortunate occurrence so impaired his health that he was for many years subject to violent pains in the head, and, as he told a biographer, until thirty years after his marriage not a week passed without one or two days of absolute confinement to his room or to his bed. "Up to this hour," he wrote towards the end of his life, " I have to endure a great fight of afflictions; can I therefore be sufficiently thankful for the merciful gift of a buoyant spirit?" Prout's father, a man of much individuality and power of mind, was a mercer in Plymouth, and he intended that his son should follow the same calling. But quite early in life a love of drawing manifested itself, and, probably on account of the boy's delicate health, his parents were not disposed to discourage it. He was fortunate in being placed under a schoolmaster who urged him to persevere with his drawing. Later on, when he was sent to the Plymouth Grammar School, he again found his headmaster, the Rev. Dr. John Bidlake, himself an amateur painter, entirely in sympathy with his artistic proclivities. Together they made many excursions in the neighbouring country.

At the Plymouth Grammar School he made the acquaintance ot Benjamin Robert Haydon (who afterwards attained notoriety by his historical paintings and by his bitter feuds with the Royal Academy), and though very different in temperament, the two lads used to wander forth together on half-holidays sketching round Mount Edgcumbe and along the shores of the Sound. It was during one of these excursions that they witnessed the wreck of the Dutton, a large "East Indiaman" which ran ashore on the 26th January 1796. The incident made a deep and lasting impression on the two boys, and it afterwards formed the subject of some of Prout's works, e.g., "The Wreck" (1815); "Dismantled Indiaman" (1819 and 1820); "Wreckers under Plymouth Citadel" (1820); "Dismasted Indiaman on Shore" (1820); "A Man-of-War Ashore" (1821) "An India- man Ashore" (1822); and "Indiaman Dismasted" (1824). In an article by Ruskin which appeared in The Art Journal in 1849 the scene is graphically described thus: "The wreck held together for many hours under the difF, rolling to and fro as the surges struck her. Haydon and Prout sat on the crags together and watched her vanish fragment by fragment into the gnashing foam. Both were equally awestruck at the time; both, on the morrow, resolved to paint their first pictures; both failed; but Haydon, always incapable of acknowledging and remaining loyal to the majesty of what he had seen, lost himself in vulgar thunder and lightning. Prout struggled to some resemblance of the actual scene, and the effect upon his mind was never effaced."

Haydon's father was a bookseller in Pike Street, Plymouth, and attached to his premises was a reading-room where local people of literary and artistic tastes used to forgather. In December 1801 John Britton, the architectural antiquary, passing through Plymouth on his way to Cornwall in search of material for his Beauties of England and Wales, visited Haydon's reading-room and there made the acquaintance of Prout, who was then a youth of seventeen. Being shown some of his sketches of rock scenery and cottages, Britton invited the young artist to accompany him to Cornwall, offering to pay all his expenses, in return for which Prout was to make sketches for the Beauties of England. Having obtained the ready consent of his parents, young Prout accepted the invitation with delight and the two set out on their journey. Britton's intention, so he tells us in an article which appeared in The Builder at the time of Prout's death, was to enter the county at Saltash and continue the journey on foot until they reached Land's End, visiting and examining the towns, seats, ancient buildings, and remarkable objects on or near the line of the main public road. "Our first day's walk," Britton wrote, "was from Plymouth to St. Germains through a heavy fall of snow. On reaching the latter borough town, our reception at the inn was not calculated to afford much comfort or a pleasant presage for the peripatetics through Cornwall in winter The object of visiting this place was to draw and describe the old parish church, which is within the grounds of the seat of Port Eliot, belonging to Lord Eliot. Prout's first task was to make a sketch of the west end of this building. .... My young artist was, however, sadly embarrassed, not knowing where to begin, how to settle the perspective, or determine the relative proportions of the heights and widths of parts. He continued before the building for four or five hours, and at last his sketch was so inaccurate in proportion and detail, that it was unfit for engraving. This was a mortifying beginning both to the author and the artist. He began another sketch the next morning, and persevered at it nearly the whole day; but still failed to obtain such a drawing as I could have engraved."

After this discouraging start the travellers moved on to Probus where Prout endeavoured to make a sketch of the church tower, a rather elaborate specimen of Cornish architecture. " A sketch of this was a long day's work," continues Britton, "and, though afterwards engraved, reflected no credit on the author or the artist. The poor fellow cried, and was really distressed, and I felt as acutely as he possibly could, for I had calculated upon having a pleasing companion in such a dreary journey, and also to obtain some correct and satisfactory sketches. On proceeding farther, we had occasion to visit certain Druidical monuments, vast rocks, monastic wells, and stone crosses, on the moors north of Liskeard. Some of these objects my young friend delineated with smartness and tolerable accuracy." They then proceeded to St. Austell and thence to Ruan Lanihorne, where they spent a very happy and comfortable sojourn of six days in the house of the Rev. John Whitaker, Prout making five or six sketches, which he presented to the "agreeable and kind Miss Whitakers" as tokens of remembrance. Britton described these sketches as "pleasing and truly picturesque." One appears to have impressed him specially. It depicted "the church, the parsonage, some cottages mixing with trees, the waters of the River Fall (sic), the moors in the distance, and a fisherman's ragged cot in the foreground, raised against, and mixing with the mass of rocks — also, a broken boat, with nets, sails, etc. in the foreground."

The next halting-place was Truro, where Prout made a sketch of the church. This, however, failed to satisfy Britton and convinced him that it was useless to proceed any further with the arrangement. The two therefore parted company, Prout returning to Plymouth by coach, and Britton continuing on foot to Land's End. "This parting was on perfectly good terms," wrote Britton, "though exceedingly mortifying to both parties; for his skill as an artist had been impeached, and I had to pay a few pounds for a speculation which completely failed. It will be found in the sequel that this connection and these adventures led to events which ultimately crowned the artist with fame and fortune." After his return to Plymouth Prout wrote a grateful letter to Britton, in which he said: "On Friday morning, after an unpleasant journey, I arrived at Plymouth. . . . I hope the latter part of your journey has proved better than the former. The remembrance of Ruan will never be eradicated from my memory. I am at present very busy learning perspective. When better qualified to draw buildings, I will visit Launceston, Tavistock, etc., and try to make some correct sketches which may be proper for the Beauties. My father is much obliged for your attentions to me, as I am, though conscious of my own unworthiness."

If it failed in the object Britton had in view, the tour was of the greatest benefit to Prout, for it proved that he was deficient in drawing and knowledge of perspective, and on his return he worked diligently to remedy these shortcomings. He studied and sketched at every opportunity, with the result that in the following May he was able to send Britton several sketches of Launceston, Tavistock, Oakhampton Castle, and other places, which, the latter tells us, " manifested very considerable improvement in perspective lines, proportions, and architectural details, and created a sensation with lovers of art." A few of these sketches were later engraved for the Beauties of England, and others for another of Britton's publications. The Antiquarian and Topographical Cabinet.

So much encouragement did Prout receive that he decided to accept an invitation from Britton to come to London and try his fortune there. " The immediate effect of this change of position," wrote Ruskin, " was what might easily have been foretold, upon a mind naturally sensitive, diffident, and enthusiastic. It was a heavy dis- couragement. The youth felt that he had much to eradicate and more to learn, and hardly knew at first how to avail himself of the advantages presented by the study of the works of Turner, Girtin, Cousins, and others. But he had resolution and ambition as well as modesty He had every inducement to begin the race, in the clearer guidance and nobler ends which the very works that had disheartened him afforded and pointed out; and the first firm and certain step was made." For two years Prout lived with Britton in Wilderness Row, Clerkenwell, during which period he spent much time studying and copying the sketches and drawings by Turner, Hearne, Alexander, Mackenzie, Cotman and others in the possession of his patron. Sometimes the young artist was taken to the studios of Benjamin West and Northcote, both of whom gave him valuable advice. On one occasion the former greatly delighted Prout by giving him some instruction in the principles of light and shadow, making several drawings to illustrate his points. This lesson made an indelible impression on the mind of the pupil and Prout often referred to it in later years with gratitude.

Haydon came to London soon after Prout and speedily attracted the notice of the younger artists by his personal eccentricities and precocity of genius. Prout was on friendly terms with him, but never very familiar. "There were but few traits of similitude of disposition in the two," says Britton. " One was modest, diffident, and mild: the other did not evince in his personal or professional character either of these amiable qualities." In 1803 and 1804 Prout was sent by Britton to Cambridge, Essex, and Wiltshire to make sketches of buildings, monuments and scenery, some of them being engraved for the Beauties of England and others for Architectural Antiquities, from which fact we may imply that Prout now enjoyed his patron's full confidence. In 1803 Prout exhibited for the first time at the Royal Academy, his "Bennet's Cottage on the Tamar, near Plymouth," being hung amongst the water-colours, while the following year he was represented by "St. Keynes' Well, Cornwall." In 1805, however, his health broke down and he was compelled to return to his home in Devonshire. This year three of his drawings were hung at the Royal Academy Exhibition — "Oakhampton Castle, Devonshire," "Farleigh Castle, Somersetshire," and "The Grand Porch to Malmesbury Abbey Church, Wiltshire." Up to the time of his first visit to London Prout had not shown any decided leaning towards the class of subject which ultimately gained him fame. Many of his earlier efforts were inspired by the beautiful scenery in the neighbourhood of his home. Whole days, we are told, from dawn to night, were devoted to the study of the objects of his early interest, the ivy-mantled bridges, mossy water-mills, and rock-built cottages, which characterise the valley scenery of Devonshire. This direct sketching from nature, and his strong love of truth, saved him from developing a cramped and mannered style. He was, too, considerably interested in the shipping which formed so great a part of the life of his native town; indeed, his marine drawings figured at exhibitions up till as late as 1839. During his visit to London, however, we find some indication of the direction in which his art was gradually tending. His three pictures exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1805, already mentioned, were of architectural subjects, and though for some years landscapes and marine subjects continued to occupy most of his attention, his love of ancient and picturesque buildings manifested itself in many of his drawings, especially those which were made for the various publications to which he contributed. A letter to Britton, dated October 16th, 1805, is published in Roget's History of the "Old Water-Colour" Society, to which admirable and ex- haustive work we are indebted for some of the details of Prout's career which are given here. This letter shows that on his return to Devonshire, after the breakdown of his health in London, Prout soon occupied himself in sketching the scenery of his native country. "I am just returned after a months visit to the Dartmoors," he wrote. "I feel much strength from the influence of its pure air, and little Prout stands as firm as a Lion. My object has not been so much to make sketches as to find health. She lives on the highest towers. I have her blessing. The subjects in my portfolio are generally rock-scenery, most of them colored and highly finished from nature. ... I have made sketches of the vale at Lidford, Oakhampton and castle, the cross and chapel at South-Zeal, Crediton, the Logan-stone, etc. ... A little London news will be very acceptable. I still am tormented with a great partiality to the great city, the hope of ever seeing it again is on a slight foundation." Several of the sketches referred to in this letter appeared later in the Devon volume of the Beauties of England and Wales, some being executed by other artists from Prout's drawings.

During the next year Prout remained in Devonshire, where he was chiefly occupied in making sketches, most of which he sold to Palser, of Westminster Bridge Road, for five shillings a-piece. This dealer was evidently a keen judge of artistic merit, for besides his early appreciation of Prout's work he was also one of the first to recognize the budding genius of David Cox. In 1808 Prout again exhibited at the Royal Academy, where he was represented by two works, "View on Dartmoor" and "Arthur's Castle at Tintagel, Cornwall." His address is given in the Catalogue as 55, Poland Street, so that the hope expressed in his letter to Britton quoted above was soon to be realized. He appears to have finally left Plymouth in 1807 and settled in London. The following year he sent another Devonshire drawing to the Royal Academy, and for the first time he exhibited at the British Institution, "The Water-mill and Manor House near Plymouth" being the title of his work. In 1810 he showed two drawings at the Institution (one a sketch of the fire at Billingsgate), and one at Somerset House. In this year he was elected a member of the Associated Artists (or Painters) in Water-Colours, with which Society he was a fertile exhibitor until it ceased to exist. During his three seasons at its Bond Street Gallery he showed no less than thirty drawings, including views in Devonshire and Kent and a num- ber of studies in shipping. In 1810 Prout married Elizabeth, only surviving daughter of Captain Gillespie, a Cornishman and large shipowner, and settled at No. 4, Brixton Place, Stockwell, where he resided for many years.

Prout's position as an artist was now fairly established. Not only were his pictures to be seen in most of the leading exhibitions, but his topo- graphic sketches which appeared in some of the popular publications also served to keep his name before the public. Reference to his con- tributions to Britton's Beauties of England and Wales and Antiquarian and Topographical Cabinet has already been made. In addition to these, thirty prints after his sketches were published by W. Clarke, of New Bond Street, during 1810-11, in a series entitled Relics of Antiquity. The work of several other artists was also represented in this publica- tion. Two years later appeared Prout's Village Scenery, published by T. Falser. This is a set of eleven coloured plates "drawn and etched by Samuel Prout." Much of his time was now given up to teaching, and in 1813 R. Ackermann published the first of Prout's educational works. It was called Rudiments of Landscape, in Progressive Studies, and was issued in three parts, each containing twenty-four plates. Part I. shows picturesque studies, in soft-ground etching. In Part II. the shadows are indicated in aquatint. Part III. contains coloured aqua- tints. The accompanying letterpress is sound and practical. This work was the forerunner of many others which Prout prepared for the use of students, and we shall have occasion to refer later to the more important of them.

Four works by Prout were hung in the Royal Academy exhibition of 1812, including a view of "Freshwater, Isle of Wight," and in 1813 and 1814 he was represented by seven and four pictures respectively. But in spite of this generous treatment his connection with the Academy appears to have gradually come to an end. It was 1817 before he again showed there, and then he was represented by a single work. An interval of nine years elapsed before another picture, "The Ducal Palace, Venice," was hung. The following year, 1827, two more Continental subjects found their way to the Academy, but after that his name does not again appear in the catalogue. This severance of his connection with the Royal Academy may be accounted for by the fact that in 1815 Prout exhibited for the first time at the Oil and Water-Colour Society (now known as the "Old" Water-Colour Society) and thus commenced a long and honourable association with that body. Between that date and the time of his death he sent to its exhibitions no less than 547 drawings, the majority of which represented the zenith of his work as a water-colourist. The seven in the 1815 exhibition included drawings of Durham Bridge, Jedburgh Abbey and Kelso Abbey, from which we may imply that he had previously been visiting the North; while his drawings of Old Shoreham Church, Worthing, Beachy Head and Hastings, shown in the 1816 and 1817 exhibitions, are evidences of a tour on the South coast. To the 1818 exhibition he again contributed seven works, four of them marine subjects, and the following year the eight drawings he sent included a "Dismasted Indiaman," to the inspiration of which we have referred on pages 2 and 3. Up till now his name had appeared in the catalogues among the ordinary exhibitors, but in 18 19 he was elected a member of the Society. This year was an eventful one for Prout for two other reasons. First, it marked the end of what may be called the earlier period of his art; second, it was the occasion of his first visit to the Continent. (Ruskin gives the date of this first visit as "about 1818," and Redgrave says definitely that it took place in that year. But Roget states, on the authority of a son of the artist, that this notable event did not happen until 1819, and the later date is to some extent confirmed by the fact that the first group of Front's Continental subjects was exhibited in 1820, at the "Old" Water-Colour Society's exhibition.) It is true that in the following years a fewviews of English scenery and some marine subjects figure amongst the drawings he exhibited, but henceforth Prout's interest was centred almost entirely in his Continental drawings.

In the foregoing pages the steady progress of Prout's career has been briefly traced, from the time when John Britton first encouraged the young artist by taking him on a sketching tour in Cornwall, to the eve of Prout's first visit to the Continent. We will now consider the result of this visit in the light of the important bearing it had upon the subsequent development of his art. It is generally admitted that had Prout never visited the Continent, had he been content to continue to the end as a painter of English scenery and marine pieces, he would never have attained to anything approaching the position he ultimately reached. By carefully studying the works of the masters of water-colour, and by sedulously sketching at every opportunity, he had gained for himself an honourable position amongst his fellow artists; while the numerous plates after his drawings which appeared in various publications had brought him considerable popularity. But this earlier work gives no indication of the development of that genius which was now to manifest itself

Ruskin has admirably described Prout's first visit to France, in an article which appeared in The Art Journal in 1849, as follows: "His health showed signs of increasing weakness, and a short trial of Continental air was recommended. The route by Havre to Rouen was chosen, and Prout found himself for the first time in the grotesque labyrinths of the Norman streets. There are few minds so apathetic as to receive no impulse of new delight trom their first acquaintance with Continental scenery and architecture; and Rouen was of all the cities of France, the richest in those objects with which the painter's mind had the profoundest sympathy. It was other then than it is now; revolutionary fury had indeed spent itself upon many of its noblest monuments, but the interference of modern restoration or improve- ment was unknown. . . , All was at unity with itself, and the city lay under its guarding hills, one labyrinth of delight, its grey and fretted towers, misty in their magnificence of height, letting the sky like blue enamel through the foiled spaces of their crowns of open work; the walls and gates of its countless churches wardered by saintly groups of solemn statuary; clasped about by wandering stems of sculptured leafage; and crowned by fretted niche and fairy pediment — meshed like gossamer with inextricable tracery. . . The painter's vocation was fixed from that hour. The first effect upon his mind was irrepressible enthusiasm, with a strong feeling of a new-born attachment to Art, in a new world of exceeding interest. Previous impressions were presently obliterated, and the old embankments of fancy gave way to the force of overwhelming anticipations, forming another and a wider channel for its future course."

This eloquent and picturesque description of Prout's first impressions of the beauties of Rouen is doubtless in the main correct, but, judging by the titles of the drawings exhibited the following year, which were obviously the outcome of this first visit to France, the scenery of Nor- mandy appears to have inspired him quite as much as the architectural beauties of the town. "On the Seine at Duclair"; "At Fecamp, Normandy"; "Near Yvetot, Normandy"; "Scene on the Seine, near Rouen"; "Harfleur, Normandy"; and "Etretat, on the Coast of Normandy," suggest that he had not altogether thrown off his love for the themes of his earlier period, and only in the "St. Maclou, Rouen," and " Croix de Pierre, Rouen," do we find any indication of the new spirit which had taken possession of his artistic soul. With these Normandy drawings he exhibited eight English subjects, mostly marine, including three of the wrecked East Indiaman. More drawings of Normandy appeared in the 1821 exhibition, and in that year he visited Belgium and the Rhine provinces, with the result that in 1822 he exhibited drawings of "Lahnstein on the Rhine"; "Metz"; "Strasbourg"; "Liege"; "Mayence"; "Andernach on the Rhine"; "Rheinfels, from St. Goarshausen on the Rhine"; and "Cat, from St. Goar on the Rhine." These were accompanied by two more versions of the wreck of the Dutton — "Boats returning from a Wreck" and "An Indiaman Ashore," — drawings of "Scarborough" and "On the Lid, Devon," and two sea-pieces. But, with the exception of one or two marine sketches, these were the last English subjects Prout exhibited. From this time on to 1851 he showed year after year nothing but Continental pictures. To the exhibitions of the "Old" Water-Colour Society he sent between four and five hundred in all, and in addition to these he executed, for various art dealers and private patrons, many other drawings of foreign towns which were never publicly exhibited. About fifty views of France, Belgium, and Germany were shown in 1823 and 1824, one of Rouen Cathedral being of particular interest, as this grand old mediaeval pile was partly destroyed by fire shortly after Prout made his sketch. That the pubhc was not slow to appreciate this remarkable development in Prout's art may be gathered from the fact that all his Continental drawings at the 1822 exhibition were sold on the opening day. His brother artists, too, were generous in their praise. Especially interesting is a notice of the 1824 exhibition which appeared in the Somerset House Gazette, whose editor and critic, W. H. Pyne, the painter, possessed a keen artistic insight and a subtle sense of humour. "Much of the additional interest of the two or three last exhibitions of the Society," he wrote, "has been derived from the introduction of many fine topographical works, from the pictorial scenery of the Continent. We had begun to tire of the endless repetitions of Tintern Abbey from within, and Tintern Abbey from without, and the same by moonlight, and twilight, and every other light in which taste and talent could compose variations to the wornout theme. So with our castles — old Harlech, sturdy Conway, and lofty Carnarvon, have every year, of late, lost a century at least ot their antiquity, by being so constantly brought before us, and if not let alone, will soon cease to be venerable. On the screen farthest from the entrance to this exhibition, are three topographical repre- sentations, which, for boldness of style, and picturesque feeling, we think superior to any works of the kind, of any school, ancient or modern. Had some hireling, itinerant, graphic ferret unearthed these treasures from the site of some Dutch burgomaster's villa, with the initials of old Rembrandt — had they been a little worm-eaten, stained, and torn, the edges corroded, and had they smelt of Vry (or even damp) antiquity,' what a fortune had it been for the finder. These admirable traits of modern talent, however, do attract, and we were gratified in listening to the encomiums of many able judges upon their extraordinary merit. The subjects are 'At Frankfort,' ' South Porch of Rouen Cathedral,' 'Porch of Ratisbonne Cathedral.' Such original examples of the picturesque give a new impulse to art There are some views of towns, and some river scenes, of large dimensions, by Mr. Prout, which, for pictorial character, originality of effect, depth of tone, and general energy of style, excel all his former works, and may be regarded as wonders in watercolours,"

In 1824 was issued Prout's first series of lithographic drawings ot Continental subjects. It consisted of twenty-four or twenty-five plates (increased in a later edition to thirty) and was published by Ackermann under the title Illustrations of the Rhine, drawn from Nature and on Stone by S. Prout. These were followed by other and more important series of lithographs, to which we shall return later. During the next twenty years Prout made frequent journeys to the Continent in search of subjects to satisfy the enthusiasm which had been aroused by his earlier visits to France and the Rhine. In spite of his delicate health and the discomforts of travelling, his quest took him far afield, to Utrecht and Brunswick in the North, to Rome in the South, and as far Eest as Prague, in Bohemia. Each year the results of these tours were to be seen at the annual exhibitions of the Water-Colour Society, and were received with delight by the artists and connoisseurs. And here it may be mentioned that, in spite of the popularity which his works enjoyed, he was always modest as regards his prices. He supplied certain country dealers, with whom he had been associated for many years, with drawings of an agreed size, about 14 or 15 inches, at a fixed price of six guineas each; while the drawings he made for exhibition he priced slightly higher. According to Ruskin, to the last he never raised his prices to his old customers, they could always have as many drawings as they wanted at six guineas each. This statement is scarcely borne out in a somewhat painful letter Prout wrote two years before his death to Hewett, the Leamington dealer, in which he said: "For a long time I have been at the seaside, in miserable health, scarcely able to leave the sofa and incapable of the least exertion even to writing a letter. . . . I know, my dear friend, that your kindness and liberality will not raise the question about prices; but I am a great fidget and always fearful lest they should be beyond a saleable amount, as I wish my kind patrons to benefit themselves as well as myself. On looking at the drawing this morning, it did not appear up to the mark, and I felt half inclined to say something less than ten guineas; but it took me a fortnight, and had my best attention. ... In consequence of old age and continued indisposition the quantity of the work will be lessened, but as family requirements will be the same I must ask kind friends to allow a small advance of prices, and what has been charged three guineas and half must be four guineas, though I hope ten guineas will answer for size sent." This letter not only proves that Prout did receive more than six guineas for his drawings, but it also shows how conscientiously he endeavoured to carry out his contracts. In the light of the modest sums mentioned here, it is interesting to note that in 1868, sixteen years after his death, one of Prout's drawings of Nuremberg was sold at public auction for just over one thousand pounds.

In 1824 Prout made his first journey to Italy and was deeply impressed by the architectural beauties of Venice, which later inspired some of his best-known drawings. "Since Gentile Bellini," wrote Ruskin, "no one had regarded the palaces of Venice with so affectionate an understanding of the purpose and expression of their wealth of detail. In this respect the City of the Sea has been, and remains peculiarly his own; there is, probably, no single piazza nor sea-paved street from St. Georgio in Aliga to the Arsenal, of which Prout has not in order drawn every fragment of pictorial material. Probably not a pillar in Venice but occurs in some one of his innumer- able studies; while the peculiarly beautiful and varied arrangements underwhich he has treated the angle formed by St. Mark's Church with the Doge's palace, have not only made every successful drawing of those buildings by any other hand look like plagiarism, but have added (and what is this but indeed to paint the lily!) another charm to the spot itself." Five Italian subjects were included amongst the dozen drawings Prout sent to the Water-Colour exhibition of 1 825 — "Pontedi Rialto, Venice" (two views); "Ponte della Canonica, Venice"; "Portico di Ottavia, Rome"; and "Place St. Antoine, Padua," and henceforth his drawings of Italy, and especially his Venetian subjects, figured pro- minently amongst his exhibited works until 1851, the last year he was represented.

It is unnecessary to follow in detail Prout's artistic progress from 1825 onwards. Each year he continued to send regularly to the Water-Colour exhibition a dozen or more drawings, and with the exception of three marine pictures — the inevitable "Indiaman Ashore" (183 1); "A Ship- wreck "(1834); and "After the Storm" (1839) — all were of architec- tural subjects from sketches made in Belgium, France, Germany, Italy and Switzerland.

In 1829 Prout was appointed "Painter in Water-Colours in Ordinary to His Majesty," a similar honour being bestowed upon him by Queen Victoria and Prince Albert. He retained this distinction until his death. In 1830 he was elected a Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries. In spite of the amount of time he spent travelling about the Continent in search of subjects, and the large number of drawings he produced each year either for exhibition or publication, Prout still found opportunities for personal teaching, and in addition he prepared some admirable educational works containing sound and practical hints for students and illustrated by his own sketches. Of the publications of this character issued before the Continental period reference has already been made (p. 8) to the Rudiments of Landscape, published in 1813. Six years later appeared Samuel Prout's New Drawing-Book in the manner of Chalk, containing Twelve Views in the West of England, and this was followed in 1821 by a companion series, Samuel Proufs Views in the North of England. These were both issued from Ackermann's Repository in the Strand. In the interval which elapsed between the publication ot the two works just mentioned appeared A Series of Easy Lessons in Landscape Drawing, which was really a supplementary volume to the Rudiments. But more important than any of these earlier educational works were those which were issued nearly twenty years later, when Prout's art had reached its maturity. In Hints on Light and Shadow, Composition, etc., as applicable to Landscape Painting, first published in 1838, the notes which accompany the plates are especially interesting because they are offered, the artist tells us, "as the basis of his practice, and the result of his experience." Equally engaging is Prout's Microcosm, which was published three years later. It contains numerous lithographic reproductions from the artist's sketch-book of groups of figures, shipping, and other picturesque objects; but of even more value to the student are the remarks on The Importance of Figures, when we consider with what unerring judgment and skill Prout introduced figures into his compositions. "It would be difficult to over-rate," he says, "the importance of correctly introducing figures into a picture. There are scenes where they would destroy the impressive and peculiar effect which characterises the spot; while in others they are so essential that, if omitted, the representation would appear deficient and imperfect. Figures always give cheerfulness, and in a degree according to their number. In the streets and marketplaces of foreign towns they are indispensable, being crowded 'like flies in a summer day,' and the quantity giving character. Figures are of much importance in every respect, but none should be introduced at random; each must have its proper place, and always tend to the completeness of the picture. It should be constantly borne in mind that the effect will entirely depend on the skill and forethought with which such combinations arc made. The want of arrangement is easily discovered: it makes all the distinction between the commonplace, and what is built on principle and right feeling. Figures should always be characteristic and appropriate, as they identify scenes. They are also invaluable as an honest means of introducing lights, darks, and colours. They arc as essential as a scale, leading the eye from one part of a picture to another, and giving to each part its true proportions. When many figures are introduced into a picture, there should always be one principal group and smaller groups, with here and there detached figures, to express distances, and render the composi- tion and effect more picturesque. It cannot be too often repeated, that without some scheme of arrangement an assemblage of objects will only be confused, and the very number and diversity of parts will but perplex and bewilder the eye." The Microcosm was followed by An Elementary Drawing-Book of Landscape and Buildings; and finally appeared Sketches at Home and Abroad, containing hints on the acquirement of freedom of execution and breadth of effect in land- scape painting. In addition to these educational works Prout made many drawings for reproduction in various topographical books. Most of these were engraved, or drawn on the stone by other hands. It is impossible to deal with these illustrations in detail here, and reference will only be made to the two most important and successful series of drawings made direct on the stone by Prout himself, and published under the titles Facsimiles of Sketches made in Flanders and Germany (1833) and Sketches in France, Switzerland and Italy (circa 1839). The plates in monotone after Prout which accompany this article were all reproduced from these two works and we shall have occasion to deal with them more fully later.

In 1835 Prout moved from Brixton Place to No. 2, Bedford Terrace, Clapham Rise; but the following year a severe pulmonary attack compelled him to leave London and reside at Hastings, where he remained for some years. This banishment appears to have depressed him considerably, and in a letter to Hewett he wrote, "If you ask how I am — most wretched. Plenty of sea in which I cannot swim — this is not my element and therefore I die daily — both body and mind." By 1840, however, his health had so far improved that he was able to spend a part of the year in London, at 39, Torrington Square, returning to Hastings for the winter months; and in 1845 he left Hastings altogether, establishing himself at No. 5, De Crespigny Terrace, Camberwell, which remained his home until his death seven years later.

In 1846 Prout had so far recovered his health that he was able to make a journey to Normandy. This, however, proved to be his last visit to the Continent, and he returned home "a sad wreck," as he described his condition. From now until the end he grew steadily weaker; but he was still able to work, "During the last six or seven years of his life," wrote S. C. Hall, in his delightful volume of reminiscences, Retrospect of a Long Life, "I sometimes (not often, for I knew that conversation was frequently burdensome to him) found my way into his quiet studio at Camberwell, where, like a delicate exotic, requiring the most careful treatment to retain life in it, he would, to use his own expression, keep himself 'warm and snug.' There he might be seen at his easel throwing his rich and beautiful colouring over a sketch of some old palace of Venice or time-worn cathedral of Flanders; and, though suffering much from pain and weakness, ever cheerful, ever thankful that he had strength sufficient to carry on his work. It was rarely that he could begin his labours before the middle of the day, when, if tolerably free from pain, he would continue to paint until the night was advanced." Notwithstanding the lingering nature of his illness Prout's end was sudden, for he passed away at his home in a fit of apoplexy on February 10th, 1852, at the age of sixty-eight, leaving a widow, one son, Samuel Gillespie (also an artist), and three daughters, Rebecca, Elizabeth and Isabella. His nephew and pupil, John Skinner Prout, achieved considerable success as a painter, and while referring to Samuel Prout's descendants I wish to acknowledge my indebtedness to his great grand-daughter, Miss Edith M. Prout, herself an artist, who has kindly furnished me with some particulars of his life. "No member of his profession," wrote S. C. Hall, " ever lived to be more thoroughly respected — beloved indeed — by his brother artists; no man ever gave more unquestionable evidence of a gentle and generous spirit, or more truly deserved the esteem in which he was universally held. His always delicate health, instead of souring his temper, made him more considerate and thoughtful of the troubles and trials of others; ever ready to assist the young with the counsels of experience. He was a fine example of upright perseverance and indefatigable industry combined with suavity of manners, and those endearing attributes of character which invariably blend with admir- ation of the artist affection for the man. ... A finer example of meekness, gentleness, and patience I never knew, nor one to whom the epithet of ' a sincere Christian ' in its manifold acceptations, might with greater truth be applied."

It would not be possible to bring to a close more appropriately this brief biographical survey than by quoting the above sympathetic tribute to the personal qualities of Samuel Prout.

Let us now consider some aspects of Prout's art as exemplified in the drawings of his second and greater period, a period in which the old and picturesque architecture of the Continent inspired him to give full expression to his artistic individuality. It is not necessary to possess great architectural knowledge to appreciate the charm of one of Prout's characteristic drawings. But to enjoy its more subtle beauties one must to some extent share with the artist that sympathy with the subject which is manifest in his work. "An artist must possess two qualities," said Josef Israels, "sentiment and the power to paint, and one is no use without the other, though the greater of these is sentiment; for an artist cannot successfully paint a subject which does not arouse his emotion." Prout's sentiment was the picturesque, and to really understand his work one must have a feeling for archi- tecture of this character. Love of the picturesque may be easily traced in the works of Prout's earlier period; and it was this same feature in the architecture of Rouen which stimulated his artistic perception and opened out to him a new field of pictorial interest. In interpreting the charm of the time-worn buildings of the Continent he revealed his natural genius and adopted a technique which, if not entirely original, came to him as a logical means of expression. As a draughtsman with the lead pencil Prout had few equals, and as his health did not permit him to work long in the open air his original sketch was usually made in this medium. "His drawings, prepared for the Water-colour room," wrote Ruskin,"were usually no more than mechanical abstracts, made absolutely for support of his household, from the really vivid sketches which, with the whole instinct and joy of his nature, he made all through the cities of ancient Christendom, without an instant of flagging energy, and without a thought of money payment. They became to him afterwards a precious library, of which he never parted with a single volume as long as he lived." After the death of the artist many of these lead pencil drawings were sold and consequently dispersed; but several were shown in the Galleries of the Fine Art Society, London, in 1879—80, at a loan exhibition of drawings by Prout and William Hunt. In their spontaneity and expressive vitality Prout's pencil sketches have seldom been equalled. Every touch had its intent and meaning, not a superfluous line was added, and he never failed to preserve the feeling of freedom and freshness. He attached the utmost importance to the necessity for sound draughtsmanship. "Correct drawing," he wrote, " is essential to every great work of art; nothing can atone for the want of it, as without it all other excellences will be valueless," and his lead pencil sketches bear eloquent testimony to the faultless- ness of his own draughtsmanship.

Nor was he less happy in the manipulation of the reed pen which he employed in his finished drawings to outline the compositions. "The reed pen outline and peculiar touch of Prout are the only means of expressing the crumbling character of stone," said Ruskin, and it is generally agreed that no other artist has so successfully suggested the texture and aspect of old arid decaying buildings. Redgrave charges Prout with hiding his lack of perception of beauty and refinement of detail under the broad markings of the reed pen. Was it not his comprehensive vision and freedom of style which impelled him to aim at generalisation, to suggest only the essentials and to avoid all distracting details? I venture to think that had Prout introduced into his drawings laboured delineations of archi- tectural details his work would have lost one of its principal charms and most of its artistic significance. Prout himself has admirably expressed his views on this particular point in his Hints on Light and Shadow, thus: "Minute and elaborately finished pictures never strongly impress the mind, and are but mere curiosities to gratify persons insensible to higher excellences. Poetry does not consist in words alone; there must be sentiment and fancy, combination and arrangement. An analogous principle may be traced in music, and equally so in painting: the minor details are forgotten in the charm produced by the whole." These views, though sound enough in principle, would probably have been somewhat modified had they been written a few years later; the masterpieces of the pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, which aroused such a stormy controversy amongst art critics a year or two before Prout's death, could hardly have been dismissed as "mere curiosities to gratify persons insensible to higher excellences," nor as pictures which "never strongly impress the mind." It would be interesting, too, to know Prout's estimate of the carefully-wrought works of his contemporary, William Hunt. Prout's broken line and peculiar touch were particularly well adapted to the rendering of ancient Gothic architecture, for they enabled him to express as no other method could the character of time-worn masonry, chipped, mutilated and weather-beaten. And it is for this reason that we find his drawings and lithographs of the Gothic buildings of France and Germany more interesting, more convincing and more expressive of his individuality than his views of Venice and other Italian places, where the character of the buildings was less amenable to the same technique. In spite of the popularity of the drawings of Venice, Milan, etc., it is the Northern Gothic rather than the Italian Gothic and Renaissance subjects which seem to me to embody the vital and finest qualities of Prout's art.

Apart from his gifts as a draughtsman, Prout possessed a happy sense of composition, and was well versed in all that pertains to the build- ing-up of a picture. We have only to examine the reproductions given in this volume to realize this. "The chief business of the artist," he said, "should be to generalize ideas: he must possess feeling to avail himself of those occasional combinations which embellish, ennoble, and give grace to his subject." With his keen and compre- hensive vision he first conceived the scene and grasped at once the essentials of his picture, grouping and arranging his material to express the unity of the whole. Each individual feature was so disposed as to keep it subservient to the entire scheme and to preserve the balance of the composition. Each object had its proper place, and nothing was allowed to obtrude unduly, while no detail was introduced without intention.

Left: View in Ghent. Right: The interior of St. Mark's, Venice.

Mention has already been made of Prout's skill in introducing figures into his compositions. It is one of the most striking characteristics of his art. He peopled his scenes with picturesquely clad figures, either in groups or singly, which seem to have guided naturally into the picture; yet with such thought have they been placed that to remove them would seriously impair the beauty and balance of the whole design. They give life and movement to the scene, and often in his water-colours afford him a means of introducing a happy note of colour, as in the "View in Ghent," reproduced here in facsimile (Plate I.). He used them skilfully, too, to indicate the height of buildings, to suggest distance, and to lead the eye from one part of the picture to another. Like Turner's figures, in many instances they are not individually well drawn, but they are never stiff or wooden; they move quietly along some quaint old street, or we find them grouped naturally, buying and selling in a busy market-place, while in the interior of St. Mark's, Venice (Plate LVII), Prout has admirably conveyed in the pose of the worshippers a feeling of reverence. In the same drawing, too, and even more in the interior of Milan Cathedral (Plate L.), is displayed his remarkable "perception of true magnitude."

Another interesting feature of Prout's art was the manner in which he manipulated light and shade in order to obtain the effect of chiaroscuro he desired. In his Hints on Light and Shadow he gives some indication of his methods and reveals his keen sense of values. "The exact quantity of light and shadow cannot be suggested," he says, "as different subjects require different proportions. The best practice is to form one broad mass, to keep other masses quite subordi- nate, and particularly to avoid equal quantities. A point of light, or a portion, or object strongly relieved, should always be preserved to give clearness and strength to the rest. A similar contrast may be repeated in several parts of the picture; but unless in smaller quanti- ties, the intention will be frustrated." A careful examination of Prout's drawings, either in water-colour or lithography, will show how successfully he applied these principles. The broad distribution of light and shade, the richness of the shadows and the play of the sunlight, give vivacity to the composition and form some of the principal charms of his work.

Prout's sense of colour was less distinguished than his gift of drawing, or it may be that he did not have the same opportunity of developing it. As Ruskin has pointed out, the subjects of Cornwall and Devonshire, by which his mind was first formed, were mostly discouraging in colour, if not gloomy and offensive; grey blocks of whinstone, black timbers, and broken walls of clay needed no iridescent illustration. The Continental subjects of his later period were often quite as independent of colour, and the original sketches were made under circumstances which restricted him to the use of the lead pencil as his medium. Nevertheless, the colour schemes he adopted in many of his water-colours were agreeable, if lacking inspiration, and the following extract from one of his letters throws some light on his methods: "Avoid patches of colour. The same colour, in a degree, should tint every part of your drawing, which may be done by freely working one tint in with another; that is, to let them unite before they dry on your paper. Always mix up a good quantity of colour before you begin, and rather float in your general tints, than very deliberately put one colour on after another." The colours he suggests are: —

Reds — Indian Red and Lake.

Browns — Burnt Sienna, Vandyke Brown, and Burnt Umber.

Yellows — Raw Sienna, Roman and Yellow Ochre, Dark Brown- Pink, and Gamboge.

Blue — Indigo,

and, he adds, "Byrne's Brown, No. 1, is a useful colour for dark touches, it being clear and gummy. For waterfalls, keep to grey in your forms and light and shade, slightly tinting over it the reflected colours. . . In old houses, etc., add Burnt Sienna to your Grey, Dark Brown-Pink, Raw Sienna, etc., varying them according to your feeling and the knowledge of local tints. In my foregrounds and nearer parts of buildings I sometimes run into dark grey, yellows, and browns, so as to render the effect of «o colour, and though it may sometimes appear dingy, touches of transparent colour, such as Raw Sienna, Byrne's Brown, etc., will clear out your effect."

Lithography was introduced into this country at the beginning of the nineteenth century, and Prout was among the first English artists to exploit Senefelder's new process. His earliest dated lithograph is the drawing which appeared in Senefelder's Complete Course of Lithography (1819) as "A Drawing on Paper transferred on Stone," and he contributed to some of Hullmandel's publications which were issued during the following year. But his finest work upon the stone was not produced until some years later when he had mastered the technical peculiarities of the medium, and discovered that as a means of render- ing the most distinctive feature of his draughtsmanship, the broken touch, it was invaluable. He found in lithography, as he had in the lead pencil, an ideal means of pictorial expression. As Cosmo Monkhouse has said, " Of all artists whose works have been reproduced by lithography, the typical instance of exact affinity between the artist and the process is Prout." His broad and vigorous touch and freedom of execution were particularly well adapted for drawing upon the stone, and his keen appreciation of the specific qualities of the mediumgaveto his productions an artistic significance which has placed them amongst the most successful and best known achievements of their kind.

Of the lithographic works of Prout the most important, as we have already said, are the two series entitled Facsimiles of Sketches made in Flanders and Germany and Sketches in France, Switzerland and Italy. The first was published in 1833 and the second about six years later. Of these folios Ruskin wrote, in his Modern Painters, "Both are fine, and the Brussels, Louvain, Cologne, and Nuremberg, subjects of the one, together with the Tours, Amboise, Geneva and Sion of the other, exhibit substantial qualities of stone and wood drawing, together with an ideal appreciation of the present active vital being of the cities, such as nothing else has ever approached. Their value is much increased by the circumstance of their being drawn by the artist's own hand upon the stone, and by the subsequent manly recklessness of subordinate parts (in works of this kind, be it remembered, much is subordinate), which is of all characters of execution the most refreshing." The plates in monotone after Prout shown here are reproduced from these two famous series and give a very good idea of the quality and beauty of the originals. Of the two sets the Flanders and Germany sketches are the more interesting, in that they are drawn with more freedom and bear more emphatically the impress of Prout's personal vision and touch; while the drawings of France, Italy and Switzerland are some- what laborious in treatment and do not convey the same feeling of distinctive spontaneity. The sketches of Flanders and Germany number fifty and the average dimensions of the lithographic surface are about 17 by 11 inches; the France, Switzerland and Italy folio includes only twenty-six drawings, measuring about 16 by 11 inches. It is not necessary, even if space permitted, to describe in detail the various plates, but a brief consideration of the more interesting ot them may suffice.

Left: Chartres. Right: Castle Chapel at Amboise. [Click on these images to enlarge them.]

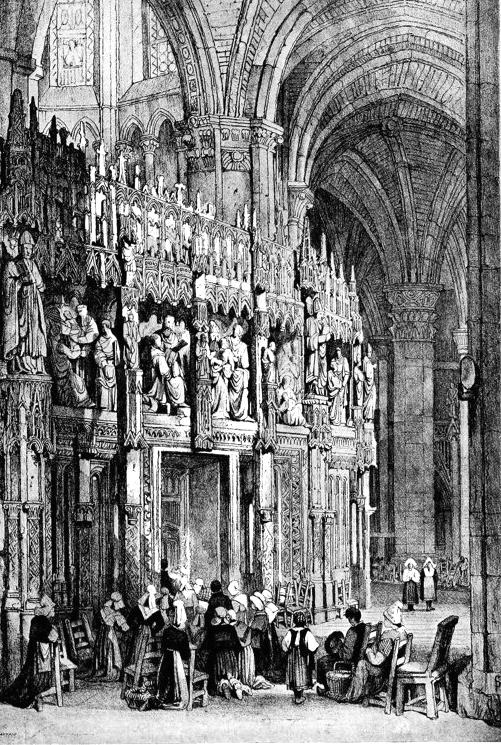

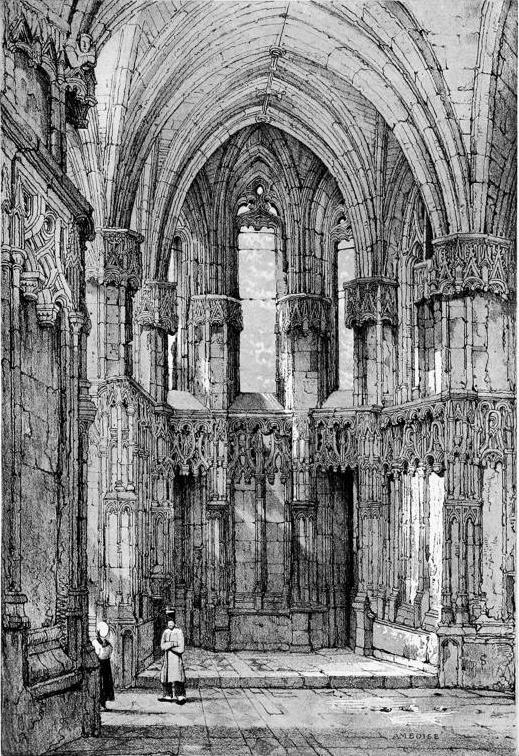

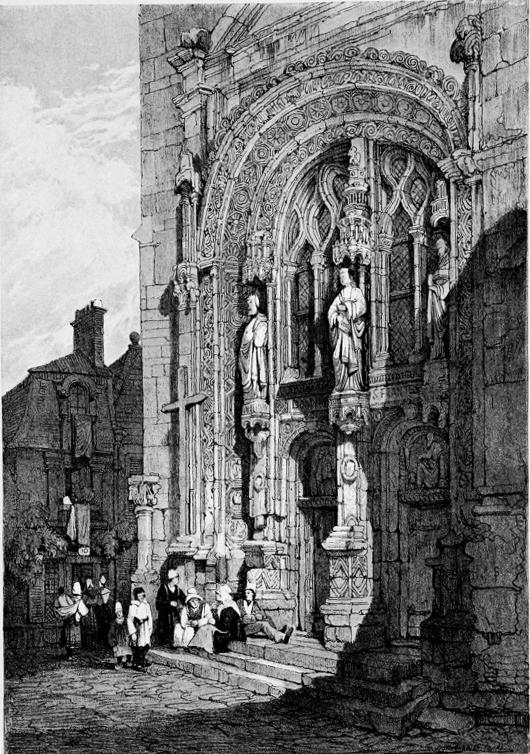

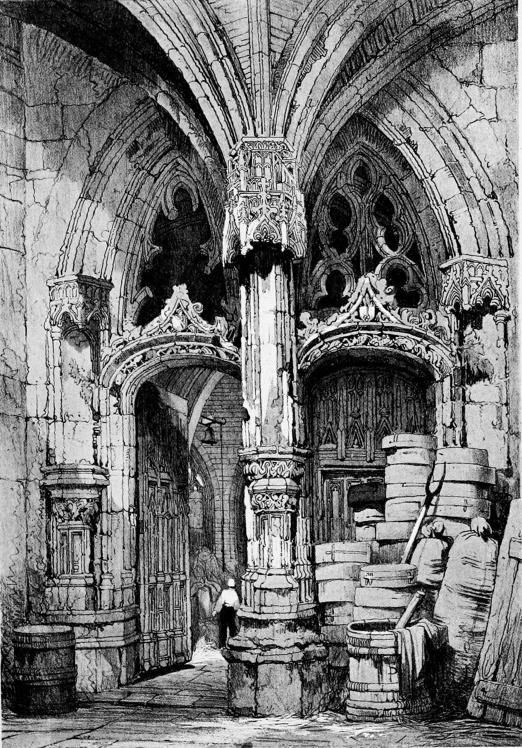

To take them in the order in which they appear here, we will deal with the French subjects first. The interior of the Cathedral at Chartres (Plate III) is an elaborate composition, and some- what overwhelmed by the wealth of architectural detail. For this reason it compares unfavourably with the dignified rendering of the Castle Chapel at Amboise (Plate VI.), which must be accounted amongst Prout's finest interiors. Here the carved detail is sufficiently defined to show the beauty of its character; but it has not been allowed to disturb the quiet unity of the whole. The drawing of the crumbling, broken masonry, and the feehng of height which is given to the building by the introduction of the two figures, without which it would be impossible to form an idea of the dimensions of the chapel, are distinctive of Prout's methods. But perhaps the most successful, as it is the most characteristic, of the French set is the drawing ot the porch of St. Symphorien, Tours (Plate IV.), which is executed with remarkable care and feeling, and displays Prout's happy sense of composition. The play of light upon the group ot figures and upon the decorative details of the buildingis particularly striking and serves to give a subtle vitality to the scene. The broken touch is here employed with unerring skill and judgment, leaving an agreeable impression which no highly -finished rendering of the subject could ever give.

Left: The porch of St. Symphorien, Tours. Right: Corn Hall, Tours. [Click on these images to enlarge them.]

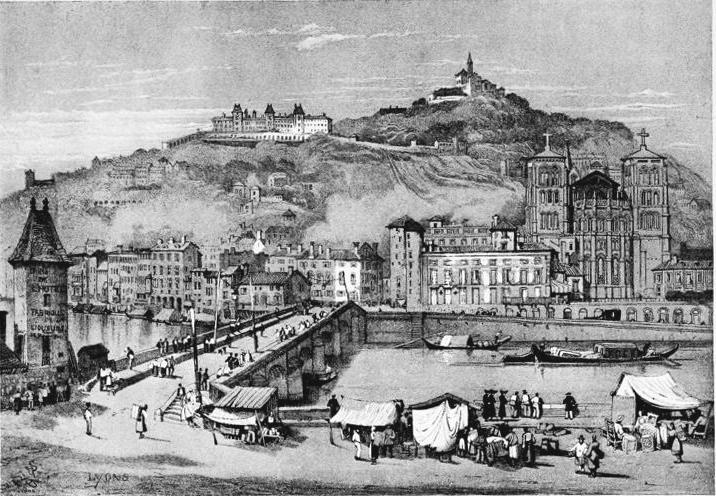

The view of the interior of an ancient church at Tours, afterwards used as the Corn Hall (Plate V.), is not particularly interesting; the view in Lyons showing a bridge over the Saone and the Cathedral of St. Jean to the right (Plate VII.) is a pleasing composition, but it does not represent the most engaging side of Prout's art. The two Strasbourg drawings which follow (we give, as Prout has done, the French spelling) are noteworthy for the clever suggestion, especially in Plate IX., of the great height of the Minster tower (it rises to 465 feet), which reveals Prout's fine sense of scale. Delightfully picturesque are the quaint old half-timber houses seen in Plate VIII., showing that the artist was as happy in giving the texture of wood as he was in rendering the character of old masonry.

“The view in Lyons showing a bridge over the Saone and the Cathedral of St. Jean to the right”.

We turn to the drawings of Belgium with mingled feelings of regret and gratitude. Regret for the terrible fate which has recently befallen some of the incomparable monuments of ancient architecture they depict; and gratitude for the precious record of their beauty which Prout has left us in these drawings. His sympathy with his subjects is manifest, for they appealed to his artistic sense as no other scenes had done, stirring him to pictorial eloquence. What happy inspiration is revealed in his view in Antwerp (Plate XI.) with its busy street under the shadow of the noble tower of the cathedral. With what care and convincing truth has he drawn the Hotel de Ville, Brussels (Plate XII.), one of the most beautiful buildings in Belgium, with its graceful tower and crowded marketplace. Yet for impressive beauty, and as a technical achievement, the drawing of the Hotel de Ville, Louvain (Plate XV.), with its richness of architectural embellishment cleverly and adequately suggested, makes perhaps a deeper appeal. Note, too, how in this drawing the lamp which is suspended over the street breaks up the monotonous tone of the building. As evidence of Prout's com- plete mastery of his medium this lithograph could not be surpassed. The Halles, Bruges (Plate XIII.), dominated by its fine belfry tower, has always been a fruitful source of inspiration for artists, but its peculiar proportions have never been more strikingly rendered than they are here; though as an example of Prout's delightful sense of composition the view of Ghent which follows it is more worthy of note. And here we may reter to another "View in Ghent," a water-colour drawing which is reproduced in colours, as a frontispiece to this volume. It is a picturesque composition, and as an example of the artist's work in this medium is characteristic. The drawing has been executed from a point looking towards the beautiful tower of St. Bavon, and on the right is seen a corner of the Hotel de Ville. The reed pen outline has been skilfully used and adds considerably to the agreeable effect of the whole, while the arrangement of light and shade is a pleasing feature of the work.

Left: La Halle, Bruges. Right: Hotel de Ville, Brussells. ]

In the spacious view in Malines, seen in Plate XVII., the artist's keen and comprehensive vision and fine sense of arrangement are well displayed, as is also his masterly draughtsmanship; nor is he less successful in the Tournai (Plate XIX.) with its isolated belfry, dating from the twelfth century. The view of the Hotel de Ville at Utrecht (Plate XX.) should not, strictly speaking, appear in this work, but as it is among the best of the Flanders series it was decided to include it.

It is, I venture to think, in his renderings of the mediaeval towns and villages of the Rhine that we find Prout in his happiest and most alluring mood. Here again his sympathy with his subject is manifest in every drawing, and his picturesque interpretation makes an irresistible appeal. The view in Cologne (Plate XXI.) is not one of the most attractive subjects, but as an example of the artist's ability to give distinction to a simple composition it is interesting. The draw- ing of Andernach, which follows it, is one of the finest of the Rhine series, both on account of the rare quality of the draughtsmanship and the soft gradation of tones. Referring to the Coblence drawing (Plate XXIII.) Ruskin wrote: "I have always held this lithograph to show all Front's qualities in supreme perfection." There are many who will agree with this judgment, although there are other drawings in this set of which the same might be said with equal justice. A remarkable monument is the Roman Pillar at Igel, on the Moselle, (Plate XXIV.) . The time-worn reliefs representing mythological and other scenes are treated with skill and commendable restraint, while Prout has once more introduced a figure for the purpose of suggesting height. No highly-finished drawing could better convey the decorated character of the pillar, nor the texture of the sandstone. Seldom has the artist pictured a more peaceful and charming scene than the Braubach-on-the-Rhine (Plate XXV.), with its quaint and highly-ornamented Gasthaus and picturesque group of figures. Noteworthy, too, is his simple treatment of the water and of the hills in the back- ground. A striking contrast to this restful scene is the view in Mayence (Plate XXVI.), with its motley crowd of marketers. With what delicate yet certain touch is drawn the cathedral in the background, bathed in brilliant sunlight. But as an example of skilful treatment of light and shade the street scene in Frankfurt (Plate XXVII.) is even more notable. The old Saxon houses seen on the right are interesting and present an opportunity to the artist for the display of his wood drawing. The second drawing of Frankfurt, with the noble cathedral tower rising in the background, is more truly characteristic of Prout. The view in Wiirzburg (Plate XXIX.) is a striking composition, with the fortress of Marienberg in the distance and the old main bridge adorned with statues of saints; but it is probable that the second view of the town interested the artist more, for it gave greater opportunity for picturesque treatment. The two views of Bamberg which follow do not call for special mention.

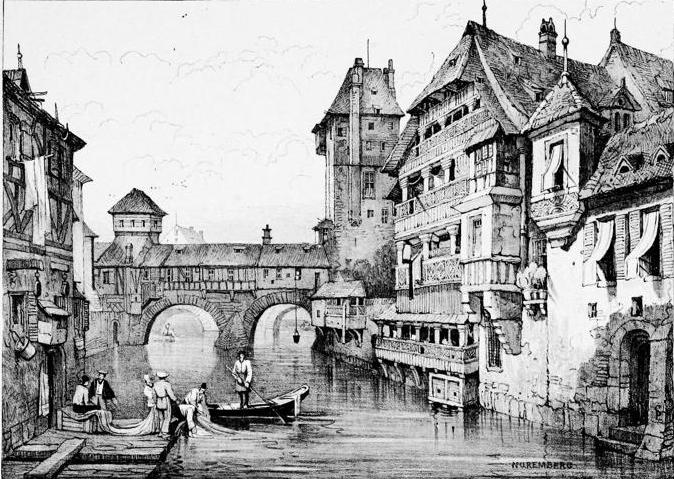

Left: Nuremberg. “ — in many ways one of the most arresting compositions Prout ever produced.”]

The drawing of Nuremberg (Plate XXXIII.) is in many ways one of the most arresting compositions Prout ever produced. It is permeated with that spirit of romance and mediaeval legend which one associates with the town and recalls those lines of Longfellow's poem which seem to bear a special significance at the present time: —

" Not thy Councils, nor thy Kaisers, win for thee the world's regard;

But thy painter, Albrecht Dilrer, and Hans Sachs, the cobbler-bard."

Prout has interpreted the scene in the spirit of the poet, informing it with an almost dramatic beauty. The drawing of the well at Nuremberg (Plate XXXIV.) has a peculiarinterest on account of a remarkable statement Ruskin made regarding it. "This study is one of the most beautiful," he wrote, "but also, one of the most imaginative that ever Prout made — highly exceptional and curious. The speciality of Nuremberg is, that its walls are of stone, but its windows — especially those in the roof, for craning-up merchandise — are of wood. All the projecting windows and all the dormers in this square are of wood. But Prout could not stand the inconsistency, and deliberately petrifies all the wood. Very naughty of him ! I have nothing to say in extenuation of this offence; and, alas ! secondly, the houses have, in reality, only three stories, and he has put a fourth on, out of his inner consciousness! I never knew him do such a thing before or since; but the end of it is, that the drawing of Nuremberg is immensely more Nuremberg than the town itself, and quite a glorious piece ot medieval character."

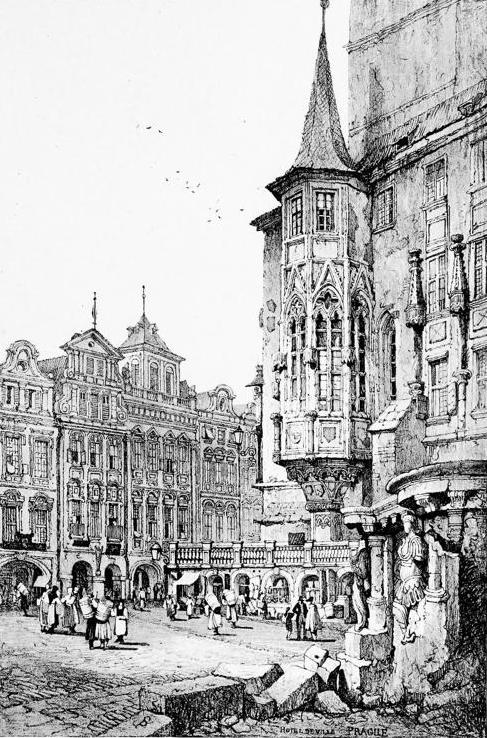

Of the two Ratisbon subjects (Plates XXXV. and XXXVI.), that ot the peculiar triangular porch of the cathedral is a fine example of Prout's drawing of the more robust character, executed with a frankness and confidence which are somewhat lacking in the second view, though this, too, is broadly treated. Another virile drawing is that of the Town Hall at Ulm (Plate XXXVIII.), with its highly ornate fountain, and rather violent contrasts of light and shade. It is a well-balanced composition carefully considered in every detail, a faithful interpretation, one is convinced, of the scene. One of the least attractive subjects in the German series is the view in Munich (Plate XXXIX.), though it contains much excellent and careful drawing. The two towers of the Frauen-Kirche, seen in the distance, surmounted by heavy cupolas, do not add beauty to the scene. An interesting example of Gothic architecture is the old Town Hall at Brunswick (Plate XL.), its open arcade, embellished with graceful traceries and figures of Saxon princes and their wives, possessing a decided decorative significance. Note also the artist's simple but effective treatment of the roofs. The three drawings of the Zwinger, Dresden (Plates XLL, XLII. and XLIIL), are skilfully executed, but it is doubtful whether the rococo ornamentation seen here really interested Prout, for the drawings do not reveal the same sympathy between the artist and his theme which one feels in most of the examples under consideration. The other Dresden drawing, too (Plate XLIV.), lacks the impress of Prout's artistic personality and pictorial outlook. But we find them again in the five Prague subjects which follow, all ot them admirable; and especially in the beautiful tower of the gateway (Plate XLVI.), which the artist has rendered with delightful freedom and ample definition, in the Hotel de Ville (Plate XLVII.), and in the Thein Church (Plate XLIX.).

Left: Hotel de Ville, Prague . Right: Thien Church, Prague. ]

Reference has already been made to Prout's drawings of Italy, and a careful examination of the examples shown here will, I venture to think, bear out my contention. At the same time it is not suggested that in his renderings of Italian scenes there is any lowering of Prout's artistic standard, but that his technique was not so well adapted to the successful representation of Italian architecture as it was to that of the more northern countries. Indeed, many of his Italian drawings are particularly beautiful in composition and pictorial conception, and some of the Venice subjects reveal a refinement of vision which is only found in the work of a master. Take, for instance, those oft-repeated themes. The Rialto (Plate LIII), S. Maria della Salute (Plate LIV.), and the Ducal Palace (Plate LVI); no artist has ever visualized them with more picturesque eloquence, nor suggested more successfully the glamour and spirit of the City of the Sea.

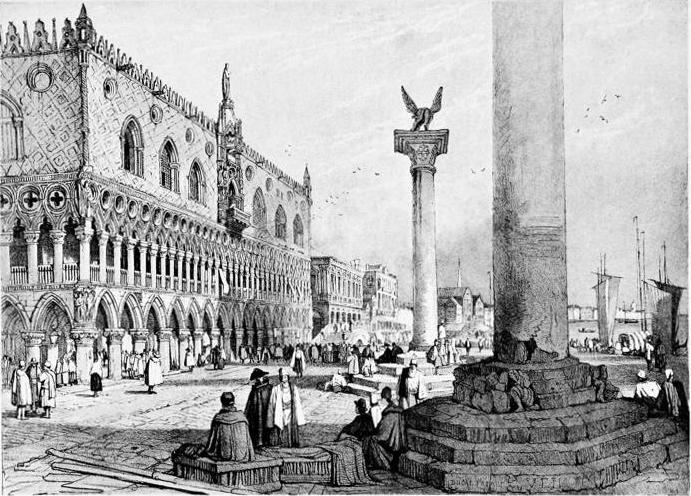

Venice — St. Mark's Square and the Palazzo Ducale

Two of Prout's finest renderings of interiors figure in the Italian series of drawings, viz., Milan Cathedral (Plate L.) and S. Mark's, Venice (Plate LVIL). Both exemplify the artist's sense of scale and magnitude, height and spaciousness being suggested with rare skill. The subtle gradations of light and shade are well managed, especially in the Venice drawing, where the richness of the darker parts and the touches of white, introduced to heighten the lights, add considerably to the beauty of the composition. Yet in its quiet dignity and imposing grandeur the Milan drawing will probably make the more lasting impression. Two other Italian subjects, Domo d'Ossola (Plate LI.) and Como (Plate LII.), should also be noticed.

Schaffhausen — “Of the Swiss drawings that of Schaffhauscn (Plate LXI.) is not only a delightful composition, but it is especially noteworthy for the beauty of its tone values, and for that reason it is one of the most successful of the artist's efforts upon the stone.”

Of the Swiss drawings that of Schaffhauscn (Plate LXI.) is not only a delightful composition, but it is especially noteworthy for the beauty of its tone values, and for that reason it is one of the most successful of the artist's efforts upon the stone. The cathedral at Lausanne (Plate LXIV.) is another splendid example of the lithographer's art. Note the pleasant luminous effect achieved by the strong light on the porch and by the beauty of the shadows. Of the two Basle drawings that of the fountain is the more characteristic, the details of the decoration being admirably drawn. The two views in Geneva do not represent the artist at his best, but his drawing of old houses at Sion (Plate LXV.), which, in spite of economy of line, has ample definition and contains all the essential pictorial features, is an attractive and interesting composition.

It is hardly necessary to point out that the drawings we have been considering in the foregoing pages have an historical as well as an artistic value; for they are beautiful and faithful records of old buildings, many of which have been materially changed by restoration, or have entirely disappeared. In most of the old towns the cathedrals and churches are all that remains of the quaint and picturesque scenes which Prout depicted with such loving care and expressive eloquence; and it is a matter for congratulation that he lived and worked before the march of modernisation and the craving for so-called improve- ment had swept away or irretrievably spoiled these noble relics of past ages. His wonderful series of Continental drawings is a precious heritage, the significance of which was never more apparent than it is to-day.

Last modified 4 March 2012