n the summer of 1850 Dr. Henry Acland, John Ruskin’s lifelong friend, introduced Stanhope to G. F. Watts who accepted him as a pupil. As Stanhope later recalled: “I set to work to study Art on the lines which [Watts] advised me to follow – namely, taking Pheidias, Michael Angelo, Tintoretto, Titian, and the old masters of that class as my examples” (Trippi 4). Daily Roddy made trips from the family home in Harley Street to Little Holland House in Kensington where Watts was the permanent guest of Thoby and Sara Prinsep. Stanhope first learned to draw drapery and anatomy as part of his studies. In a letter from Stanhope to his father early in his student days he writes:

He [Watts] says the first object is to acquire power and facility in representing any object whatsoever upon paper in black and white, and this is the surest and quickest way of arriving at that facility. After that has been obtained, the rest is relatively easy, anatomy, study of form, etc. being most necessary; and painting may follow close upon that…Watts utterly condemns all conventionality and mannerisms, and says that nothing ought to be studied (the Elgin marbles excepted) but nature; in studying anybody’s style you loose all originality and become a mannerist, which after all is nothing but copying, thereby lowering yourself to the ranks of copy-writers, door-painters etc. [Stirling 301-02]

Stanhope would have been well to remember this advice, particularly with regards to the later works he executed in Florence. In a letter of September 1852 to his mother Roddy wrote about his instruction under Watts’s guidance: “he is very fearful of influencing me in any way, and never makes a comment upon anything I show him, but only urges me on and gives me good advice about keeping in the right way” (Stirling 309). Stirling has pointed out the shortcomings of the system of teaching that Watts pursued: “Fearful of bruising ever so slightly the delicacy of an original inspiration, of marking with his own personality the individuality of effort, Watts did not sufficiently insist on the drudgery of Art and the study of classical models. Hence his pupils lacked a knowledge of technique, from which many of them suffered all their lives, and strove to fly ere they had learned to walk” (310).

It was through Watts and the salon kept by Sara Prinsep at Little Holland House that Stanhope made friends with Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Edward Burne-Jones, William Holman Hunt, Thomas Woolner, and other artists of the Pre-Raphaelite circle as well as writers like Charles Dickens, William Makepeace Thackeray, Robert Browning, Alfred Tennyson and Thomas Carlyle. It was at the Prinsep home that Stanhope was asked to participate in the decoration of the Oxford Union Debating Hall. In a letter from the summer of 1857 Stanhope describes meeting with members of the Pre-Raphaelite circle and his doubts about Rossetti’s ability to complete projects:

We had a whole Pan full of the chief Pre-Raphaelites yesterday and had a very pleasant day of it. There was Hunt, Rossetti and Collins. I submitted my picture to their inspection and I must confess that their remarks on it were very flattering and that I have evidently taken up quite a position in their eyes. Rossetti has had the painting in fresco of the Oxford Museum entrusted to him. This is really a great mistake on the part of the managers, but I suspect it is the architect’s [Benjamin Woodward] doing. He has a very ill-regulated disposition, as I believe that he has never completed a single thing that he has undertaken, and has only succeeded in finishing small things which he has managed to complete before he got tired of them; moreover he is quite unacquainted with fresco, and has never worked upon a large scale so that I expect his attempt will prove a failure. Besides this he is decorating the Union Club there in distemper…He has asked me to go and do something there, as there are several fellows working, so I shall certainly go and see, and, if it is advisable to do so, I shall take my share in the work. [Stirling 312-33]

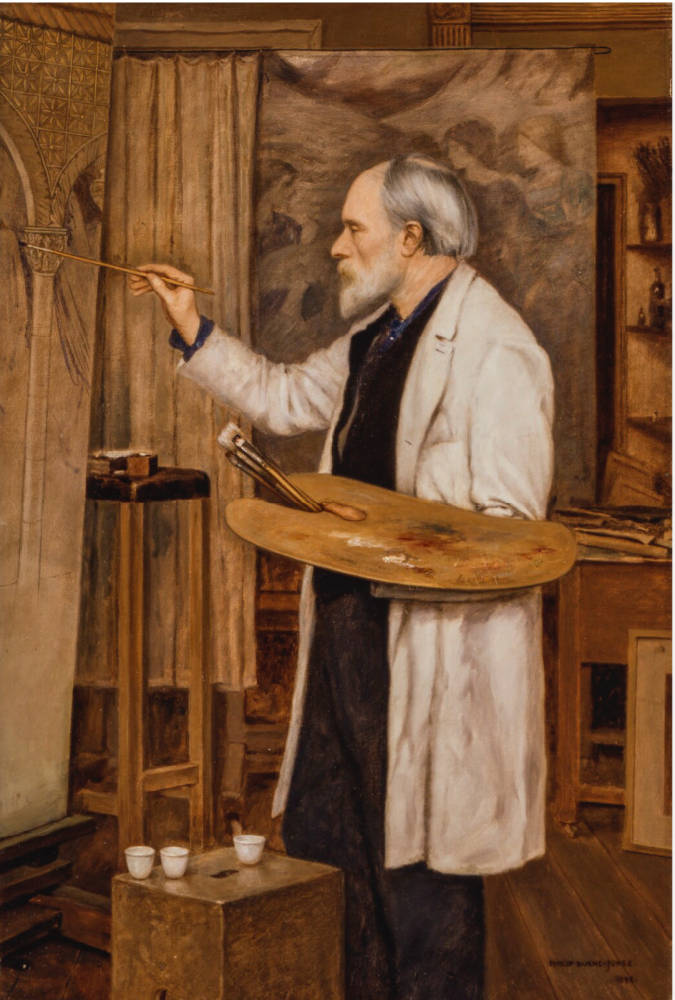

Despite his doubts, which ultimately proved all too founded, Stanhope agreed to participate, likely because his working with Watts at Lincoln’s Inn had made mural decoration attractive to him. He chose as his subject Sir Gawaine Meeting Three Damsels at a Well. From Stanhope’s perspective the major importance of his participation in this venture was a deepening of his friendship with Edward Burne-Jones. Stanhope, in a letter to Georgiana Burne-Jones talking about those days, wrote: “As time went on I found myself more and more attracted to Ned; the spaces we were decorating were next to each other, and this brought me closely in contact with him…he appeared unable to leave his picture as long as he thought he could improve it, and as I was behind with mine we had the place all to ourselves for some weeks after the rest had gone” (Burne-Jones, Memorials, 164).

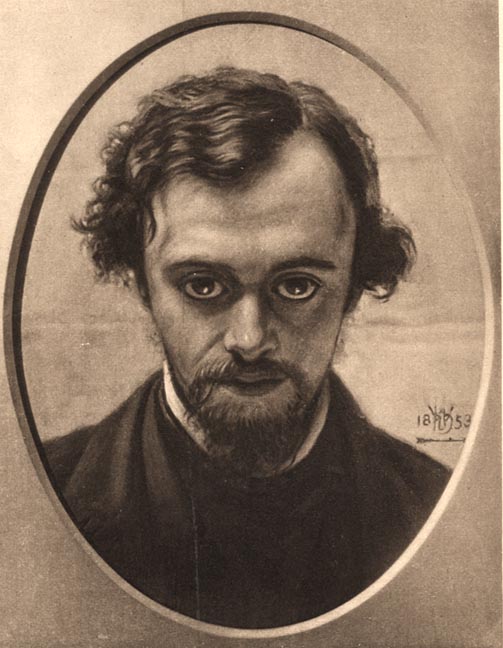

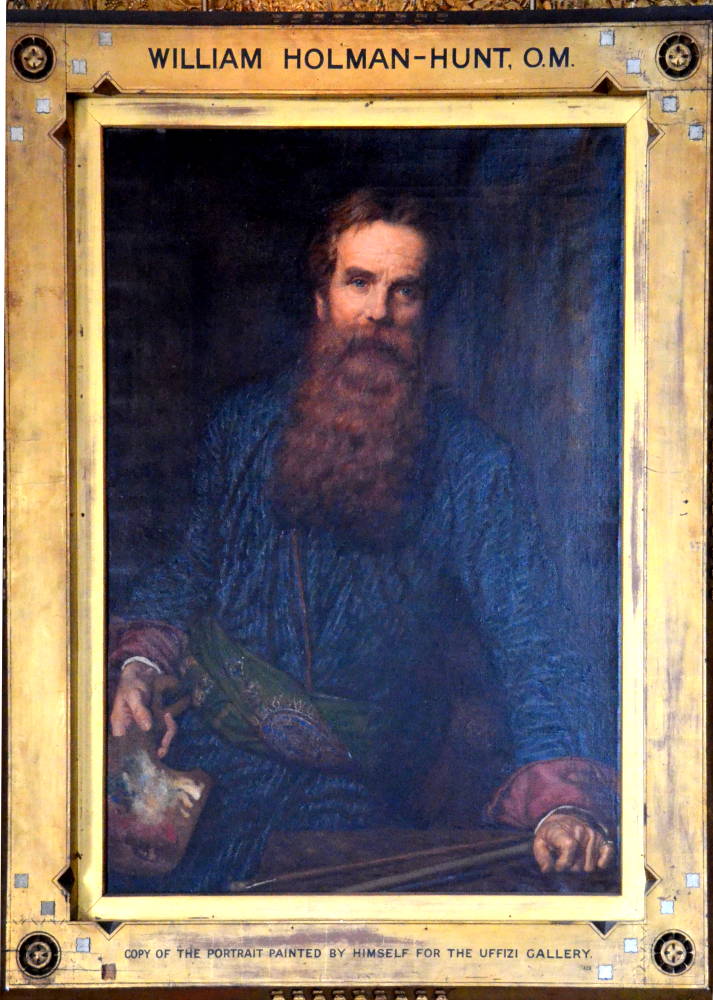

Some founding members of the Hogarth Club from left to right Ford Madox Brown’s Self-Portrait, William Holman Hunt Dante Gabriel Rossetti and his own self-portrait, and Sir Edward Coley Burne-Jones by his son. [Click on images to enlarge them and to obtain additional information.]

Stanhope’s friendships within the wider Pre-Raphaelite circle widened when he became a founder member of the Hogarth Club in 1858. George Price Boyce’s diaries of the period frequently mention Stanhope and his association with the club. On June 10, 1858 Boyce record: To Hunt’s [William Holman Hunt]. …At 7:30 we came to dinner and found in the room Wallis, Holliday [Halliday], Martineau, Barwell, and Miss Hunt. After dinner came Prinsep, Jones [Burne-Jones], Brett, Egg, F. G. Stephens, and Stanhope” (Surtees, Diaries, 24). A diary entry for October 13, 1859 mentions Boyce visiting D. G. Rossetti when Stanhope came in and admired Boca Baciata, the portrait of Fanny Cornforth that Rossetti was painting for Boyce. Boyce’s published diaries go as far as 1875 and even as late as March 9, 1874 Boyce writes: “Dined with Philip Webb at the Albion Tavern. Burne-Jones, Wm. Morris, Stanhope and Henry Wallis there, very jolly party” (Surtees, Diaries, 59). Ford Madox Brown’s diary also mentions some socializing with Stanhope. On January 26, 1866 he records, ‘out with Rae [George Rae] & to dine with Stanhope” (212). His diary entry for February 18, 1866 mentions that he went “out to see Legros, Jones, Stanhope, Prinsep, Hunt, Inchbold Etc” (213).

Despite his friendship with Burne-Jones, Morris, and Brown, Stanhope had little involvement with Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co. that was founded in 1861. He did, however, do painted panels of Pre-Raphaelite angels against a backdrop of a rose-entwined trellis set into the organ screen at the east end of the south aisle of St. Martin, Scarborough. This was the first of Stanhope’s many collaborations with the architect George Frederick Bodley for domestic and church interiors. Stanhope also designed the sculptural relief of Knowledge strangling Ignorance that was used as an embellishment on many of Bodley’s early designs for schools. His most important commission for Bodley in England was the sequence of twelve large highly decorative paintings, The Ministration of Angels on Earth, which he executed between 1876-78 for Marlborough College chapel between the windows on the north and south walls. Six stories were taken form the Old Testament and six from the New Testament. He had previously painted twelve small panels of musician angels for the east wall between 1874-75. Their other major collaboration was for Holy Trinity church, the principal Anglican church in Florence. Here Stanhope collaborated on wall decorations and painted a many panelled high altar reredos for the high altar.

Stanhope’s greatest friendship within the Pre-Raphaelite circle remained with Burne-Jones. Early in their careers Stanhope and Burne-Jones often worked together, with each artist benefiting from the association. In 1862 Stanhope had moved to Sandroyd at Cobham in Surrey. It was there, during the summer of 1863, that Burne-Jones painted The Annunciation [The Flower of God] and landscape studies for The Merciful Knight, while Stanhope worked on his later oil version of The Wine Press and Penelope. In 1870 Burne-Jones is known to have painted Love Among the Ruins in Stanhope’s new studio at his home Little Campden House on Campden Hill in London.

Even at the end of his life Burne-Jones maintained his admiration for his friend while also acknowledging his deficiencies. On January 7, 1896 he remarked to his studio assistant Thomas Rooke about Stanhope:

Faults of his pictures were what anyone could see, what any cook could see. His colour was beyond any the finest in Europe…It was a great pity that he ever saw my work or that of Botticelli’s. Though there may be a time for him yet. An extraordinary turn for landscape he had too – quite individual…and finally go to Florence where he is much better [from his asthma], though his living there has injured his work very much…But his absence from London has removed him from his proper atmosphere, and he’s got to think more and more exclusively of old pictures to the extent that he’ll almost found his own pictures on them and give up his own individuality. But I did love him [Lago, Burne-Jones Talking, 76-78]

Burne-Jones obviously recognized that becoming so influenced by the Florentine Old Masters had severely hampered the originality in Stanhope’s work and it had become much too derivative. By this time Stanhope had obviously forgotten the excellent early advice given him by Watts that “in studying anybody’s style you loose all originality and become a mannerist, which after all is nothing but copying” (Stirling, Painter of Dreams, 302).

Stanhope’s home at the Villa Nuti at Bellosguardo became the centre for the cosmopolitan artistic and literary community that lived in Florence and a place of pilgrimage for English visitors especially artists. Artists and architects known to have visited include Walter Crane, Charles Fairfax Murray, Philip Webb, and G. F. Bodley. Stanhope spent his life there almost entirely within the English colony and mixed very little with the native Italian population. In April 1873 Burne-Jones and Morris travelled to Florence on their only joint visit to Italy and spent some time there reminiscing with Stanhope at his studio. Stanhope’s niece and sometimes pupil Evelyn De Morgan and her husband William were frequent visitors, especially after they too began to spend the winters in Florence after 1892 for the sake of William’s health. It was the Stanhopes who cared for William Holman Hunt’s newborn son Cyril after his wife Fanny died in Florence of a miliary fever on December 20, 1866. The Hunts had been on their way to the Middle East but had been detained in Florence because of a travel restriction due to the outbreak of a cholera epidemic in Alexandria. Hunt then travelled on to the Holy Land alone.

Stanhope is best known today as one of the most important followers of Burne-Jones, a group that also included J. M. Strudwick, Evelyn De Morgan, Walter Crane, Sidney Meteyard, Charles Fairfax Murray, and T. M. Rooke amongst others. William Michael Rossetti in his Reminiscences summed up his own feelings in this regard:

Mr. Stanhope might originally be considered more an amateur than a professional painter, but he soon made art his vocation in life, painting in a style very visibly related to that of Burne-Jones. Whatever the style he is a man with plenty of ideas of his own, and has invented and composed several very superior works. As a rule, I do not sympathize with the “imitators of Burne-Jones”: they seem to me generally to lose their hold upon the soundness and solidity of nature, without attaining to much excellence of art, or even of artifice. Mr. Spencer Stanhope is (so far as I know) by far the most capable painter identified with this movement [222-23]

Whatever his limitations Stanhope proved to be no mere dilettante but a serious painter. He obviously did not have to paint for a living because he came from an aristocratic background and was a man of private means, which fortunately made him independent from the vagaries of the art market. His best works are the early paintings he produced in the late 1850s and 1860s before he gave way to the mannerisms that characterize his later works, especially after he had moved permanently to Florence.

Bibliography

Catalogue of Pictures and Drawings By the late R. Spencer Stanhope. With an Introduction by William De Morgan. London: Carfax & Co. Ltd, March 1909.

Burne-Jones, Georgiana. Memorials of Edward Burne-Jones. Volume 1. London: Macmillan and Co. Ltd, 1904.

Fiumara, Francesco. “A Painter Hidden. John Roddam Spencer Stanhope: His Life, His Works, His Friends. The British Period: 1829-1880.” M.A. thesis. Universita’ Di Messina, Anno Accademico 1992-93.

Lago, Mary Ed. Burne-Jones Talking. His conversations 1895-1898 preserved by his studio assistant Thomas Rooke. London: John Murray, 1982.

Rossetti, William Michael. Some Reminiscences of William Michael Rossetti. Volume 1. London: Brown Langham & Co. Ltd. 1906.

Stirling, A. M. W. “A Painter of Dreams. The Life of Roddam Spencer Stanhope, Pre-Raphaelite.” Chapter VII in A Painter of Dreams and Other Biographical Studies. London: John Lane, 1916, 287-345.

Surtees, Virginia Ed. The Diaries of George Price Boyce. Norwich: Real World, 1980.

Surtees, Virginia Ed. The Diary of Ford Madox Brown. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1981.

Trippi, Peter B. “John Roddam Spencer-Stanhope. The Early Years of a Second Generation Pre-Raphaelite 1858-73.” M.A. Thesis. Courtauld Institute of Art, University of London, 1993.

Created 30 October 2004

Last modified 6 May 2022