From the viewpoint of our twenty-first century, one might be tempted to think that Henry Scott Tuke (1858-1929), was a typically Victorian/Edwardian artist whose work, now somewhat controversial, was considered perfectly innocent in his day. A painter specialising in pictures of naked boys playing in or near the sea is no longer above the suspicion of child abuse, but his contemporaries saw nothing to raise an eyebrow about his extremely successful depictions of the sunlit flesh of young scamps. Or did they? One of the many interests of the volume published by Yale University Press is precisely to remind us of an easily overlooked fact: in the late nineteenth century, Tuke's paintings, while approved as "healthy" by the general public (67), already attracted the informed attention of those who then called themselves Uranians, adepts of an idealised paedophilia, a group among whom Tuke counted a number of friends.

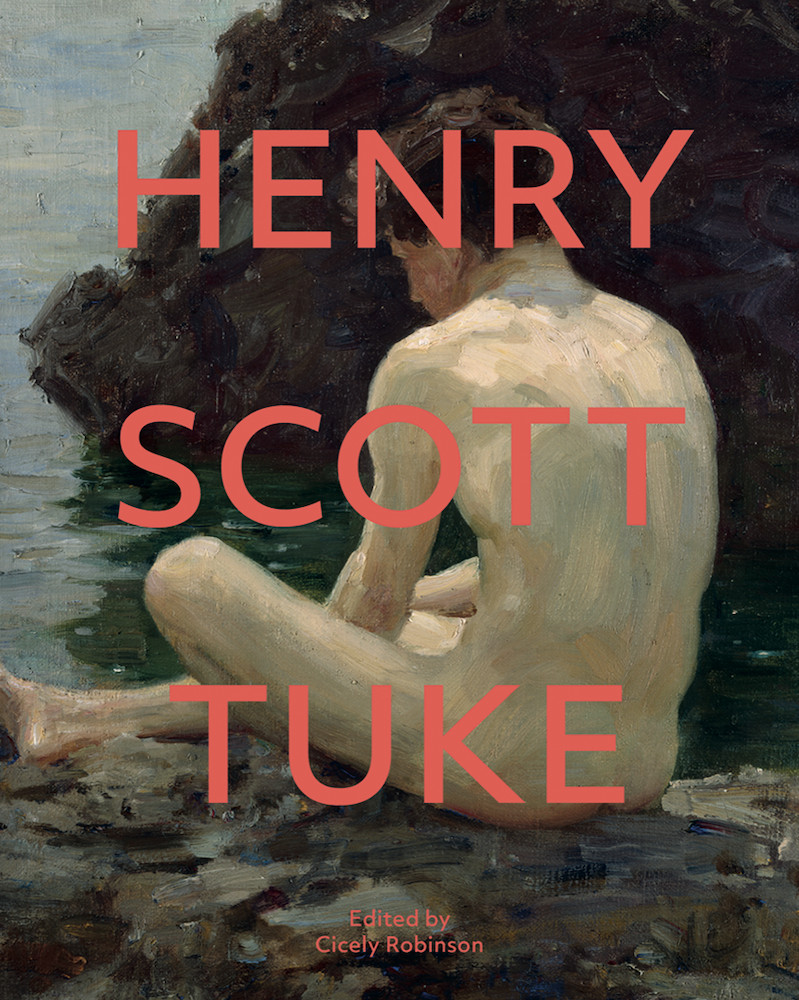

Obviously, the book edited by Cicely Robinson is not all about the possibly unsavoury undertones we now immediately detect in Tuke's work, but offers a multi-faceted approach for today's viewers. Its six chapters focus on various aspects of the artist's production, the result being "[n]either a comprehensive biography [n]or an all-encompassing, celebratory reassessment of the artist" (13). In their studies, the different authors help situate Tuke in his context, shed light on the various aspects of his career (including some forgotten trends, like his – often misguided – attempt at classical subjects) and make the artist less of a monolith.

Biographical elements are not absent from the volume, even if a bit scattered – a recapitulative chronology might have come in handy. One learns that Tuke came from a Quaker family (more about it later, as it is the object of the whole fifth chapter), that he studied at the Slade under such masters as Poynter and Legros, that while in Paris as a student of history painter Jean-Paul Laurens, he admired the work of Bastien-Lepage and met Dr Charcot, and that he eventually settled in Cornwall where his kind of naturalism was influenced by the plein-air sketches he had painted with Arthur Lemon (1850-1912). Much information about Tuke comes from his own Register of Paintings, where he took extended notes about his different works. In her own chapter, about the various boats in Tuke's career, Cicely Robinson details the different "platforms for painting" the artist used to work and to live in. Despite all sorts of environmental challenges, Tuke led a "semi-amphibious" life (55), since he also had a house in London, and because his canvasses were generally produced partly from a boat, partly from a beach. His "floating studio" also served as a backdrop for various paintings (68). Exhibiting at the RA almost every year from 1879 to 1929, he became a full member in 1914; his works were also on display at the short-lived Grosvenor Gallery in the 1880s, and at the New English Art Club.

Nicholas Tromans focuses on Tuke's family background. His father, Dr Daniel Hack Tuke, was famous in his time as a Quaker alienist, and he was credited with having introduced John Addington Symonds, the son of an expert in forensic medicine, to Havelock Ellis: the two young men co-authored a book entitled Sexual Inversion, whose publication was opposed by Dr Tuke in 1895. Tromans compares this "reticence" with Henry Scott Tuke's own silence about homosexuality, even though the painter actually contributed "to promote the pleasures of what we would now recognize as a queer gaze" (111).

All Hands to the Pumps (RA 1889).

Inevitably, a discussion of "the love that dares not speak its name" is in order when so many pictures of naked young boys and men splash their colours along the pages of the book. Victorian critics admired some works by Tuke as "manly" (40) because they reflected a certain patriotism, with their depictions of vigourous British sailors, and because the very fact of painting in the open air was in itself manly, as it meant depriving oneself of the comforts of a city studio. Such visions of masculinity as All Hands to the Pumps (RA 1889) gave Tuke worldwide fame: as commented by Mary O'Neill in her essay, his "sailor strategy . . . acted as a springboard, launching him into the art world and resulting in substantial national and international success" (53). However, Tuke did not only represent seasoned hearts of oak: in the Paris Salon in 1883, he exhibited Un jour de paresse (lost), the painting of an idle boy in a tree, and his first nude, Summer Time, appeared in 1885 at the Grosvenor Gallery. Tuke repeatedly explained that his primary interest was in capturing the effects of outdoor light on the human form, and he was not the first English artist to show pictures of naked boys messing about: the most illustrious precedent was Frederick Walker's Bathers (RA 1867), and among Tuke's contemporaries, Stott of Oldham's A Summer Day (RA 1886) immediately comes to mind. Other painters, like Philip Wilson Steer, showed naked girls (A Summer's Evening, NEAC 1888), as reminded by Andrew Stephenson in his study – it might also have been relevant to compare Tuke's work with that of Joaquín Sorolla (1863-1923) – , but Tuke's attempts at representing female nudity were rather limited and are now only known through black and white photographs: The Mermaid's Cave (rejected by the RA, 1896) used the bust of an American lady, and Perseus and Andromeda (RA 1890) was actually posed by two brothers. The artist was also criticised because he had an English boy model for Hermes at the Pool (RA 1900, later destroyed by Tuke himself), whereas a more mature and Mediterranean physique was expected for the god. Tuke's forays into mythology were rather awkward and unsuccessful, apart from those where he followed the advice given by John Addington Symonds, who suggested he gave up the paraphernalia of classical subjects in order to provide mere "transcripts from the beauty of the world" (106). His Faun (1914) is hardly more than a naked young man in a forest, without the traditional horns or goat's feet, and his best symbolist vein is illustrated by To the Morning Sun (RA 1904), a boy whose frontal nudity is masked by a semi-transparent loincloth.

Fred Walker's Bathers (RA 1867).

Even if Tuke was never accused of any improper behaviour "unlike his friend Charles Masson Fox" (131), as specified by Michael Hatt in his chapter, a whole bundle of evidence implies that the painter may well have been gay. What is certain is that he was friends with many homosexuals like Symonds, Edmund Gosse, historian Horatio Brown, or Charles Kains-Jackson, the chief editor of The Artist and Journal of Home Culture, who all paid homage to his works, notably in poems, and who discussed whether they truly showed homoerotic sympathies. Tuke's paintings were perceived by most people as evocative (of the joys of youth and summer) rather than provocative, but some saw them as coding and expressing Uranian desire, "in a visual language that had not yet been codified", according to Nicholas Tromans (104). Michael Hatt resorts to Foucault's notion of heterotopia to present Tuke's world of naked boys as "a space of alternative possibilities" where various erotic narratives can be enacted (118), and concludes that "Uranian poetry and Tuke's paintings aspire to capture the intensity of the joyful moment while mourning, explicitly or implicitly, its loss (133).

Link to Related Material

Bibliography

Robinson, Cicely, ed. Henry Scott Tuke. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2020 (paperback edition 2022). 160 pages, 125 illustrations. £20.00. ISBN: 9780300265842. [Click here to find the book on the publisher's website.]

Last modified 2 November 2023