Want to know how to navigate the Victorian Web? Click here.

Smokey Sheffield

In transcribing the following article I have followed the invaluable text of the Hathi Trust online version. I have added links to material in the Victorian Web and subtitles to mark off several of the essay’s distinct discussions. — George P. Landow .

Sheffield’s Industrial Pollution

LACK but comely." Such is Sheffield, as nearly as three short

words can describe it. It is much late in day to

venture on the demurrer that the parent home of the steel-trade is not

so black as it is painted, by a good many coats. The world has quite

made up its mind about it. Railway travellers have whirled through the blinding

smoke-fog that darkens the valley of the

Don, and have murmured to each other a

devout thanksgiving that their lot has at

least been cast in a transparent air. Adventurous visitors have stood for five minutes under the porticos of the railway stations

(both of which unceremoniously discharge

their crowds into the most unpromising

of localities), and have turned and fled.

So the bad name has been given, and the

dog has been hanged, and there's an end of

him. But while two blacks do not make a

white, half-a-dozen might very fairly be held

to reduce a capital charge to a petty offence;

and if there are not six other towns in

England with Brightsides and Attercliffes

as sooty in their habits and as Cimmerian in their aspect as Sheffield's brawny pair of arms, then the story that the ancient emporium of steel has forfeited large slices of its trade to the enterprise of younger rivals is a weak invention of the enemy, and "Steelopolis" will, with joy and pride, wear the stigma as a garland. The main peculiarity of Sheffield is that she turns her seamy side to the world and belches nine-tenths of her smoke in the faces of those who pass over the great trunk lines, instead of planting her industrial Inferno at a respectful distance from the railway-king's highway.

LACK but comely." Such is Sheffield, as nearly as three short

words can describe it. It is much late in day to

venture on the demurrer that the parent home of the steel-trade is not

so black as it is painted, by a good many coats. The world has quite

made up its mind about it. Railway travellers have whirled through the blinding

smoke-fog that darkens the valley of the

Don, and have murmured to each other a

devout thanksgiving that their lot has at

least been cast in a transparent air. Adventurous visitors have stood for five minutes under the porticos of the railway stations

(both of which unceremoniously discharge

their crowds into the most unpromising

of localities), and have turned and fled.

So the bad name has been given, and the

dog has been hanged, and there's an end of

him. But while two blacks do not make a

white, half-a-dozen might very fairly be held

to reduce a capital charge to a petty offence;

and if there are not six other towns in

England with Brightsides and Attercliffes

as sooty in their habits and as Cimmerian in their aspect as Sheffield's brawny pair of arms, then the story that the ancient emporium of steel has forfeited large slices of its trade to the enterprise of younger rivals is a weak invention of the enemy, and "Steelopolis" will, with joy and pride, wear the stigma as a garland. The main peculiarity of Sheffield is that she turns her seamy side to the world and belches nine-tenths of her smoke in the faces of those who pass over the great trunk lines, instead of planting her industrial Inferno at a respectful distance from the railway-king's highway.

Let it be settled, then, that the picture is vulgarly, unpardonably dirty; and that (since Doré is dead, and we have no apostle ready to resent the popular idea that railside Sheffield is, like waterside London, an "ugly place") there is nothing inspiring, nothing weirdly picturesque, in a sombre valley dashed with the fitful glow of a thousand naked fires. Let the Rembrandt tone go: perhaps the Turneresque aspect of Sheffield will please. The dirty picture is but a tiny panel after all — the centre-piece of a vast area of frame full of light and grace. The site of Sheffield is one of the fairest outposts of the Peak, from the noble base of which it is only separated by a few miles of slanting moor land, down which the bracing western breezes course briskly into the town. It is the "Hillsborough" of Put Yourself in His Place, which Mr. Reade describes as lying "in a basin of delight and beauty: noble slopes, broad valleys, watered by rivers and brooks of singular beauty, and fringed by fair woods." It is no great tax on the imagination to divest the Sheffield of today of its furnaces, its rumbling rolling-mills, and its brick and mortar, and to clothe its [659/660] sharp crests and undulating hollows with their primaeval timber and pristine verdure. The very streets, stone-faced and smoke-stained as they are, lend the fancy a helping hand, for they are at least still romantic in their declivity, and picturesque in their unconventional variations of width and direction. Save where the highway follows the bed of a valley, it is a matter of long search to light upon half a mile of level road, recalling, to a roving mind, Jerrold's jeu d'esprit that, if Britannia really ruled the waves, it was "a pity she didn't rule them a little straighter." Which, in turn, reminds us that the subject of this paper is the staple industry of Sheffield, and not its scenic charms, nor the pedestrian penalties thereof.

The History of English Steel Cutlery and Edged Steel Tools

Though the term "staple industry" is primarily applied to the manufacture of cutlery, the remarkable developments of the steel trade have long pushed the historic craft from its stool of honour, and the anachronism is countenanced here mainly in recognition of the fact that the cutlery trade is the industry upon which the prosperity of Sheffield was built, and which has been most constant to the town. Indigenous to the soil, jealously nursed and perfected within the manor of Hallamshire, the craft remains, so far as the United Kingdom is concerned, the practical monopoly of Sheffield; while more ambitious industries which have sprung into being within the present century, and sharp crests and undulating hollows with their primaeval timber and pristine verdure. The very streets, stone-faced and smoke-stained as they are, lend the fancy a helping hand, for they are at least still romantic in their declivity, and picturesque in their unconventional variations of width and direction. Save where the highway follows the bed of a valley, it is a matter of long search to light upon half a mile of level road, re calling, to a roving mind, Jerrold'sjew d' esprit that, if Britannia really ruled the waves, it was "a pity she didn't rule them a little straighter." Which, in turn, reminds us that the subject of this paper is the staple industry of Sheffield, and not its scenic charms, nor the pedestrian penalties thereof. Though the term "staple industry" is primarily applied to the manufacture of cutlery, the remarkable developments of the steel trade have long pushed the historic craft from its stool of honour, and the anachronism is countenanced here mainly in recognition of the fact that the cutlery trade is the industry upon which the prosperity of Sheffield was built, and which has been most constant to the town. Indigenous to the soil, jealously nursed and perfected within the manor of Hallamshire, the craft remains, so far as the United Kingdom is concerned, the practical monopoly of Sheffield; while more ambitious industries which have sprung into being within the present century, and done so much to make the town the sixth largest in England, have taken to themselves wings and (led away. In the infancy of the cutlery trade Sheffield had more competitors in the home market than it has now, since, besides London, which still makes a pretence of rivalry, the making of knives was carried on at Salisbury, at Woodstock, and at Godaiming; and as arrow-heads, for the arming of the levies of the civil wars, then formed a large item in the trade, it is quite possible that the centres of production were more numerous still. The arrow-heads made in the Sheffield district, indeed, probably had much to do with determining that survival of the fittest which we witness to-day, for the Sheffield weapons were largely purchased for the use of the English forces in the wars with France, and there is credible evidence that the victors of Bosworth Field were armed with Sheffield arrows of "a very superior make, being longer, sharper, and better ground" than the common weapons. In the Poll Tax documents of the 14th century for the West Riding, arrows are specifically mentioned with knives and scythes as among the leading productions of this part of the Riding, and the representatives of the branch are designated "arrow-smiths."

The manufacture of cutting instruments in some form or other in the Sheffield district, probably dates back to the time of the Roman settlement, but the first historical reference to the existence of the iron trade is contained in a grant made about the middle of the 12th century to the monks of Kirkstead for iron-working at Kimberworth, near Rotherham; and the earliest identification of Sheffield with cutlery itself appears to be in connection with a list of articles issued from the Privy wardrobe at the Tower in 1341, which contains the entry "cultellum de Shefeld." Before 1400, the "Shefeld thwytel," or whittle, was famous all the country over, as Chaucer testifies; the "thwytel" which the immortal miller "bare in his hose," probably being some thing between a dirk and the domestic table-knife. Sheffield was at that time rather the centre of a district engaged in the production of cutlery than the sole place of manufacture, the area including Rotherham, and Ecclesfield. and extending as far as Chesterfield, one of the streets of which still bears the name of Knifesmithgate; and, as Mr. S. O. Addy has lately pointed out in the Yorkshire Archceological Journal, Sheffield, although somewhat larger, was then distinctly inferior to Botherham in social importance.

For several centuries London remained a formidable competitor with Sheffield in fine cutlery, but the special reputation of the metropolis in this respect has long passed entirely into the surgical instrument trade. in the more delicate sections of which London is still supreme. According to the historian Stow, " Richard Mathews, on Flete Bridge, was the first Englishman who attained per fection in making fine knives and knife hafts, and in the fifth year of Elizabeth he obtained a prohibition against all strangers and others from bringing any knives into England from beyond seas, which, until that time, were brought into this land by shippers lading from Flanders mid other places." Again after an allusion to the importation of cutlery in the time of Henry VIII., the same "honest chronicler" says: — "Albeit at that time, and for many hundred years before, there were made in divers parts of the kingdom many coarse and uncomely knives, and at this day the best and finest knives in the world are made in London." It is quite consistent with the traditions of Sheffield workmanship that finish and appearances should have been subordinated to utility at this time, and it is more than likely that [660/661] the alleged inferiority of the Hallamshire knives consisted solely in defects of this nature. Even as recently as fifty years ago, if we may believe McCulloch, the same idea prevailed with regard to the relative merits of London and Sheffield cutlery, and, whether from actual necessity, or by way of bolstering up the metropolitan reputation, in the reign of George III. an act was passed menacing persons who sold cutlery marked "London" or "London made," which had been manufactured outside a radius of twenty miles from the capital, with a heavy penalty. Whatever might have been the exact truth then, Sheffield manufacturers to-day "smile at the claims of long descent" preferred by the successors of Richard Mathews, and the unrepealed Georgian Act is an object of gay derision, and a nuisance to London trades men to boot. While every country iron monger can have his name and full address stamped on his blades, the metropolitan shopkeeper is perforce compelled to be' content with "Smith, Regent Street," "Brown, Strand," or " Jones, Cheapside," as the case may be.

Lord Shrewsbury and the Sheffield Steel Guilds and Unions

Finishing Knife Handles. From a Drawing by A. Morrow.

By far the most engrossing aspect of the cutlery trade of Sheffield is its history; and its history is enthralling, not because it records any remarkable vicissitudes of the industry as a craft, for its course has been singularly even and natural; not because of any dramatic developments in processes, for practically cutlery is made at this moment in the same primitive way as when the clang of the smith's hammer startled Lord Shrewsbury's deer; but for the light which the record throws upon the formation of the character, the habits of thought, and the economic theories of a body of artisans who have figured rather unfortunately in our industrial annals and to whom full justice has never quite been done. Sheffield and trades unionism will probably always be bracketed together with a sinister suggestiveness; but the theories which exploded so disastrously with their own gunpowder twenty years ago, though narrow and unsound, were not new. They had a long, and even distinguished, pedigree, for they were the lineal descendants [661/662] of the doctrines laid down under the inspiration of those great lords of the Sheffield manor who were good enough to take the infant industry under their care. The idea that the main body of the members of a trade had an inherent right to dictate to all concerned in it the terms upon which the craft should be followed had its inception in the fifteenth century, and was transmitted from generation to generation as a code of honour to be maintained at any risk and in spite of every blandishment. As time rolled on the execution of the trust grew more and more difficult. In exact proportion, indeed, as the gospel of individual liberty progressed, the difficulties of the trades unionists increased. The "black sheep" multiplied, and speckled the flock at an alarming rate. Invitations to conform to the ordinances of the trade were openly flouted. Polite appeals gave place to heated argument, argument to menace, menace to murder. And then the bubble burst; and the world lifted up its hands and said what wicked men Broadhead, and Crookes, and Hallam, and the other leading actors in the policy of assassination were, which was all painfully true; but there was nothing in the circumstances that was specially new, except that contumacy had for the first time reached such a daring pitch as to invoke the " extreme penalty " of an unwritten law three or four hundred years old.

Under the Shrewsbury régime, which extended from 1406 to 1617, a trades union was formed in the cutlery trade more tyrannous and more subversive of the best interests of the craft than anything ever dreamed of by the most despotic of demagogues of the Broadhead type. By the enactments of this institution (which, with the addition of a jury of twelve cutlers was co-existent with the court-leet of the manor), it was ordained that for twenty-eight days after August 8th in every year no work whatever should be done, nor from Christmas to the 23rd of January; that every apprentice should serve seven years before he could exercise his trade on his own account; that no person should be allowed to have more than one apprentice; that no grinding should be done during the holiday months; that no grinder should reside out of the district, within which he must have been instructed; that neither haft nor blade should be made or sold out of the liberties; that every journeyman should be at least twenty years old; that five pounds should be paid before any person entered into business — one half to go to the Earl of Shrewsbury, and the other to relieve the poor in the corporation. Wages, prices, and production were also regulated under the same paternal system. The twelve cutlers already mentioned were appointed to see that these and other rules were "strictly carried out." For a time, fines, and a wholesome fear of the mighty lord of the manor, were sufficient to ensure obedience to these ordinances, but after the last of the Shrewsbury's had been laid in his grave it was found necessary (in 1624) to obtain from parliament the charter of incorporation under which the Cutlers' Company was constituted. The preamble of the Art declared that many of the cutlery workers refused to submit to the ordinances of the trade; that they persisted in taking as many apprentices and for such a term of years as they chose, whereby it was feared that the calling would be "overthrown;" and that the workmen, owing to the absence of proper authority, " are thereby emboldened and do make such deceitful unworkmanlike ware> and sell the same in divers parts of the king dom, to the great deceit of his Majesty's subjects and scandal of the cutlers of Hallamshire, and disgrace and hindrance of the sale of cutlery and iron and steel wares then- made, and to the great impoverishment, ruin, and overthrow of multitudes of poor people.' In some respects the regulations enforced under parliamentary sanction exceeded in stringency the locally made laws, as under them the "searchers" (a section of the officials of the company) were empowered to enter houses and seize "deceitful, unworkmanlike wares," and only a certain number per year of fresh hands (and those freemen) were permitted to enter the trade.

It will be remarked that the trades unionism of this period consisted of a combination of masters and not of workmen; which is quite true, but the master cutlers of the time were themselves working artisans, only employing an apprentice or two and occasionally a journeyman, while the aims of the old and the modern unions are practically identical. One of the worthiest and most remarkable of Sheffield's old citizens, the late Mr. Samuel Roberts, describing the condition of the town in the middle of the last century, says that up to that time " Sheffield and the Sheffield cutler were but a mean place and a poor man. To be “as rich as a man of a hundred a year” was proverbially to be in the highest rank." It was not until the latter half of the eighteenth century that the trade began to shake off its self-imposed fetters, and that, under the impetus of the discovery of silver-plating and the crucible steel process, of the manufacture of Britannta metal, the opening of the Don for navigation, [662/663] and the cultivation of foreign trade, the prosperity of the town began to move at anything like a decent rate. The spell of feudalism to which Goldsmith's lines have been applied:

Thou source of all my bliss and all my woe,

Thou found'st me poor at first and keep'st me so,

was not broken till long after the potent authors thereof had ceased to rock the cradle of the craft. By the early years of the present century a new social system had taken shape, and a wide gulf was disclosed between manufacturers and artisans. The wealth which had brought the masters social dignity also brought them more enlightened views of the interests of the town, and in 1814 they very wisely obtained an Act repealing the restrictive clauses of their charter and throwing the trade open to free men and non-freemen alike. Equally natural, if not equally wise, was it that the men should take up the bearing rein where the masters had dropped it; and although, for some years before, the artisans had more or less clandestinely entered into combinations on their own account, the year 1814 marks the open adoption by them of the restrictive policy which their employers had relinquished. On this point Mr. Frank Hill, who presented an elaborate report on the trade combinations of Sheffield to the Social Science Association in 1860 (seven years before the exposure by the Outrage Commission), remarking on the action of the Cutlers' Company in 1814 says

Henceforth the policy of exclusion and protection which the masters had for some time been gradually relaxing, and had now finally abandoned, was adopted by the artisans. The workmen began to attempt by combinations, not merely to secure what they deemed fair, or at any rate practicable, advances in wage, and to resist unnecessary or avoidable reduc tions, but to aim at regulating, by minute and stringent legislation, the conduct of their respective trades.

It is easy to see, if not to excuse, how a class of men placed in much the same position (but without the legal authority) as the authors of the Shrewsbury "rules and ordinances," of the same temper, the same traditions, the same want of education, but, above all, with such a venerable and illustrious example before them, should be tempted to keep alive a policy which seemed to have been discarded to enrich men already rich, and to impoverish those already poor, and should endeavour to enforce its provisions with the only means at their command, although from the lengths to which those means ultimately went the great mass of Sheffield unionists recoiled with horror and shame. It may be remembered that the chief culprits unearthed by the Com mission were not representatives of the cutlery trade proper, some of the worst outrages having been directed against saw grinders, sickle makers, and fender grinders; but all manufacturers of tools having a cutting edge have long been admitted to the Cutlers' Company, and the traditions and customs of the parent calling pervade all the branches of the local iron and steel trade.

Luddite Attacks on New Machinery for Grinding Saws

In January, 1860, an attempt was made to blow up the works of a firm who had introduced new machinery for grinding straight saws, and the members of the firm were so alarmed by threatening letters sent to their wives that "after consulting with the saw-grinders' secretary" (Broadhead himself) they determined to withdraw the machines. Mark how the whirligig of time brought its revenge for this small success! Seven years later, Broadhead, the dictator, quivering like an aspen leaf before the Royal Commissioners, was shouting to his tool and accomplice, Crookes, in the witness-box "Tell all, Sam!" Later still, the man who blew up the saw-grinding machines was himself grinding saws by machinery only fifty yards away from the scene of his exploit, and to-day the Saw- grinders Union is the feeblest and, most harmless of all the existing combinations.

Ruskin’s Praise of Ironwork and the Guild of St. George

With all his primitive prejudices and his economic heresies the typical Sheffield cutler (using the term in its broad and obsolete sense of a craftsman in cutlery), is the best workman in the world, and his heart is as sound as his workmanship. It is no light testimony to his worth that he has won the special affection of Mr. Ruskin, who placed his matchless museum in Sheffield solely for his behoof. "I am frequently asked," said the Professor, in a statement respecting the St. George's Guild recently published,

why I chose Sheffield for it, rather than any other town. The answer is a simple one — that I acknowledge ironwork as an art always necessary and useful to man; and English work in iron as masterful of its kind. . . . Not for this reason only, however, but because Sheffield is in Yorkshire; and Yorkshire is yet, in the main temper of its inhabitants, old English, and capable, there fore, yet of the ideas of honesty and piety by which old England lived.

One great factor in this fascination which Sheffield possesses over the fervent apostle of the dignity of manual labour is doubtless to be found in the fact that it has been the lot of [663/665] the cutlery trade to give machinery, as a manufacturing agent, the cold shoulder. Every blade that is worth anything is forged upon the anvil — beaten out of the steel rod by the power of human muscle, shaped by the human eye, hardened and tempered by the human judgment, and ground upon a stone over which the workman bends low with all the laborious application of an artist adding a few delicate touches to his work. It is doubtful whether any other trade of the same magnitude has derived so little advantage from mechanical agency in essential requirements, and to this happy chance may be ascribed the survival in the Sheffield cutler of that hearty interest and wholesome pride in his work which are seldom found in workmen whose intelligence has been discounted by a precise mechanism. Upon the maintenance of this pride the maintenance of Sheffield's supremacy in the manufacture of cutlery largely depends.

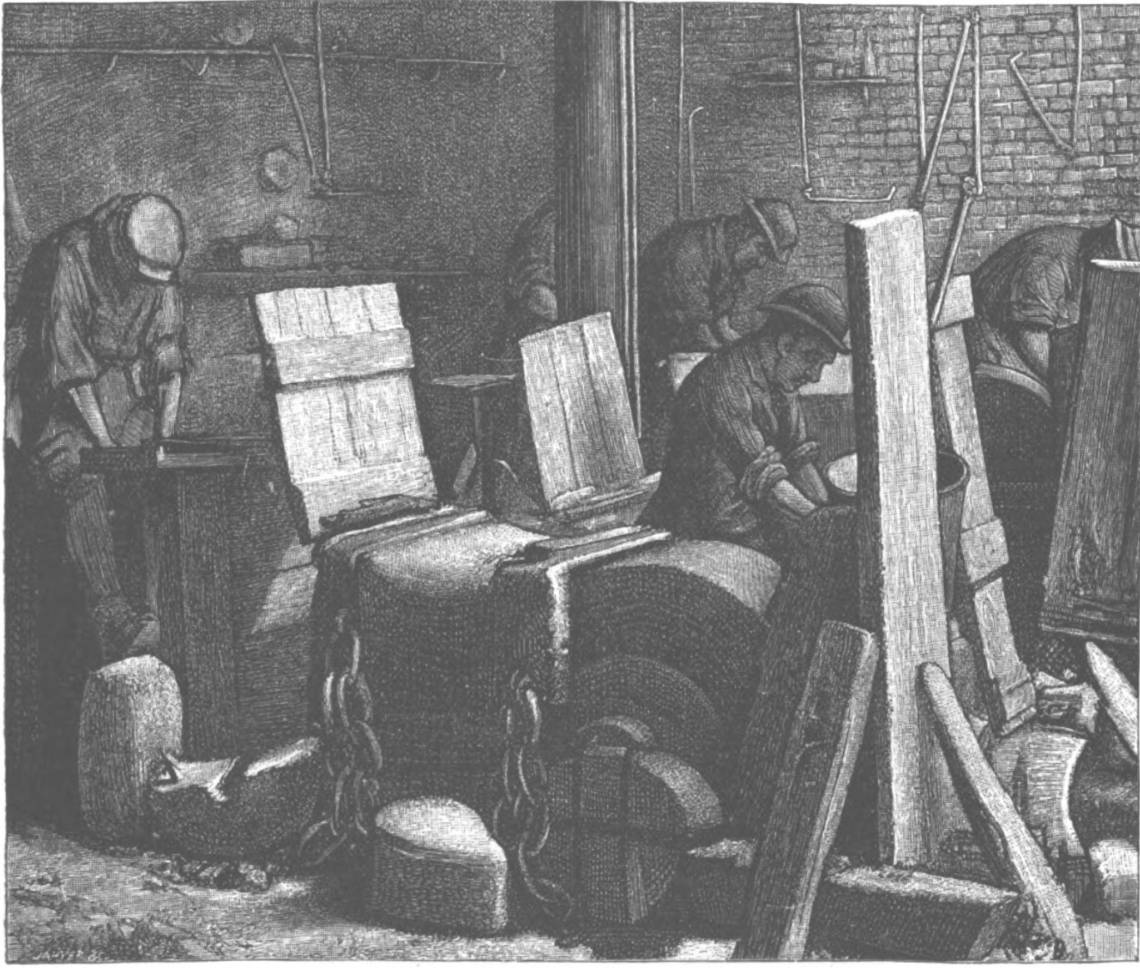

Blade Forging Shop. From a Drawing by A. Morrow.

The best knives are, and probably always will be, made by hand, and the qualities which are necessary to this system are in Sheffield hereditary. In dexterity of handling, rapidity of execution, perception of results, and honest zest, the Hallamshire forger and grinder are unapproached by any foreign workmen in the trade. With the latter the moral motive force is generally the bare necessity of earning bread and cheese; with the farmer there is the same incentive plus an inspiring local patriotism. Wherever foreign competitors have chipped Sheffield trade the end has been accomplished by adapting machinery to common work, as in America, or by stooping to the wholesale production of cutlery that won't cut, as in Germany. The German grinder a few years ago had a certain reputation for " hollow-grinding " razors, a tedious system which was well in keeping with the slow, laborious method of Teutonic workmanship; but his Sheffield con frere was not long in wresting this exotic laurel from the Hamburgher, and when the latter comes to Hallamshire and ventures to put himself in competition with the Sheffield [665/666] workmen he starves. The American grinder is not on good terms with his stone, and works perfunctorily, as one condemned to sit out so many hours per day. The ex-mayor of Sheffield, Mr. Michael Hunter, jun., when in the States a few years ago, looked in at a grinding "hull." He found the work men sitting bolt upright on their horsings, grinding "under the robin" as it is called, that is to say, holding their blades end-wise, and pointing downward, much as a youth "rides" upon a walking-stick. "Why don't you 'finger' it?" exclaimed the English visitor; but "their disdain was their reply." By "fingering" his blade the Sheffield grinder effects all those dainty touches and delicate gradations which no machine, nor no man using a machine, can impart. In France the grinding is done with the stone revolving towards the workman, who prostrates himself at full length over his work. Except in scythe-grinding, the stone turns from the English grinder, who, by merely bending over it, is enabled to throw all the weight of his shoulders into the friction. This point of the outward revolution of the stone enabled a "swarff"-stained Sheffield grinder not long ago to become a very effective art critic. A well-known local artist had painted the interior of a "hull." A couple of working men stopped before the window in which it was exhibited. One passed a complimentary remark on the performance; the other paused critically and then derisively rejoined, " Ay, but stone's runnin' t' wrong road!" The stream of sparks which had betrayed the blunder was promptly reversed.

The Dangers of the Knife-Grinder’s Work — Accidents and Breathing Metal Powders

The knife-grinder has, after all, a story to tell, and a very dismal one it is. He is environed by dangers, as completely as he is saturated with the wet "swarff" (powdered stone) which dyes him a deep saffron colour from head to toe. He sits over a tool which at any moment may send him through the roof with all the suddenness and velocity of dynamite, and he works in an attitude and (especially if he be a "dry" grinder) inhales a dust which he knows will shorten his life by ten, twenty, or even thirty years as constitution and fortune may serve him. The sharp crack of a breaking stone is an appalling sound to the occupants of a grinding-hull. A bang in a trough, a crash in the roof, and a piteous moan, and all is over. If the victim be alive he is hurried to the hospital; if dead, his crushed body is rever ently carried away. No vigilance in the master, no care in the workman, seems able to avert these periodical catastrophes. The insidious water-rot, the hidden flaw, and the unequal grain do their fatal work in spite of all precautions. To meet the destitution arising from these calamities a Grinders' Misfortune Society was established in Shef field in 1804, and at the annual festival of the members a by no means festive song, entitled The Grinders' Hardships, used to be regularly called for. The following is a verse thereof: —

"There seldom comes a day but our dairy-maid

goes wrong,

And if that does not happen, perhaps we break

a stone,

Which may wound us for life, or give us our

final blow,

For there's few that brave such hardships as we

poor grinders do."

The "dairy-maid" was the slang of the hull for the water-wheel, which, though still an important source of power in the outlying districts, was at the time the song was written an apparatus of the first importance. As to the unhealthy character of the grinder's occupation, some idea may be gathered from the following statistics which were published in a pamphlet on The Mortality, Suffering, and Diseases of Grinders, by the late Dr. Calvert Holland in 1842. Since that date, however, much has been done to mitigate the evils of the calling by the use of fans and ventilation. The figures in this case relate only to the pen-knife grinders: "160 out of 1,000 deaths above 20 years of age die in the United Kingdom between 20 and 29; in Sheffield 184; but in this branch 402. In the next period, between 30 and 39, in the kingdom at large the deaths are 136; in this town 164; but in this branch 329. The deaths under 50 years of age in the kingdom are 422; and among the pen blade grinders 640." The consequence of this state of things was that, in an age when to an illiterate and naturally convivial artisan the sophistry of " a short life and a merry one " seemed to be the only true philosophy, the grinders as a body acquired a reputation for improvidence and debauchery from which they have not yet fully recovered. There were many other inducements of a negative character to relieve the peculiar hardships of the grinder's lot with liquor, such as forced delays "when the dairy-maid went wrong, and when work was scarce or tardily given out, the independent terms upon which nearly all the Sheffield artisans work, and the impulses of a companionship in which all were of one order and of one mind. So ex travagant were the excesses of the men in this direction that even their fellow townsmen came to place them on a lower plane of the human species, and to speak of a group of persons as consisting of "three men and two grinders."

The Grinding Room. From a Drawing by A. Morrow.

As a class, however, they are rapidly improving, and there are in Sheffield to-day many striking examples of cultivated and prosperous men who have emancipated themselves from the thraldom of evil habits, and while following the trade have followed at the same time the behests of the "still small voice" within them. The most interesting branch of cutlery manufacture, as a process, is the initial business of forging. For articles in which there is no welding to be done, such as scissors and pocket knives, a single hand is sufficient, but the forging of table-blades is a "double-handed" affair, the forger himself being assisted by a striker. The visitor to Sheffield will hear the ring of the forger's hammer not merely in the neighbourhood of the great manufactories, but in places where he least expects it. He will come across a "hearth" sandwiched between private dwellings in a quiet residential street, and he will sometimes catch the rasp of the cutler's file in the dwelling house itself. It may be as well to explain here that the term "cutler," now that the division of labour has given a specific title to every branch, is used in the trade in the restricted sense of a "putter together," that is, the man who fits the blade to the handle and produces the finished article. The solitary forger's hearth, discovered in a tranquil thoroughfare, might at first sight be easily mistaken for a small stable which had suffered a severe gun powder explosion, but a second glance reveals the simple materials required to produce all that is essential in a good knife — a rod of steel, fire, hammer, water. Such are the elements out of which Mr. Ruskin's "masterful" magician will in a few moments present you with a table-blade, perfect in shape and symmetry, hard as adamant as to edge, pliable as a cane as to temper, and requiring only the grinder's touch and the cutler's halting to be fit for the table. The forger's first operation is moulding ("mooding" as he calls it) or shaping, which is done before the length of blade required is severed from the strip of steel which he holds in his hand. The steel in a table knife ends at the base of the blade; at that point a small strip of wrought iron is welded to the steel, and forms what is called the "bolster" — that is the shoulder cap which meets the handle — and the "tang," or tail, which runs down the centre of the haft. Every person given to after-dinner meditation must have noticed at the base of the blade of his knife a shaded outline like a large thumb mark. This mark indicates the union of the iron with the steel, a process which is called "shooting," and is performed jointly by the forger and his assistant. The next stage is "tanging," and consists in shaping the bolster and tang by the aid of small dies and appliances with which the anvil is fitted. The blade is now complete in shape, but has to be straightened, marked (with the manufacturer's name or other brand), hardened, and tempered, the whole operation being comprehensively called "smithing."

A Rural Grinding Mill. From a Drawing by A. Morrow. This lovely scene appears rather strangely in the context of the article about urban Sheffield, though it does show where in earlier days much of the manufacturing took place.

The straightening and marking are simple matters, but in the operation of hardening and tempering hand and eye have to be brought into delicate co-operation. Harden ing is the process by which the steel blade is changed from the nature of lead to that of glass, from an obedient ductility to a petulant [668/669 brittleness. This change is effected by plunging the heated blade into the vessel of dirty water which stands near the anvil. The operation appears ridiculous in its simplicity, but upon its performance in the right way and at the right time depends the value of your knife. For this you have to rely upon the trained judgment of the forger. Some tools will warp, or "skeller," if they are not plunged into the water in a certain way. Tools of one shape must cut the water like a knife; those of another must stab it like a dagger. Some implements, such as files, must be hardened in an old-standing solution of salt; others in a stream of running water; others again, like saws and scythes, in whale oil. The non-success of our American cousins in this mystery of hardening led some of them to the conclusion that Sheffield water was as necessary to the production of good cutlery as that of Burton is to the brewing of good beer. So a few years ago a party of enter prising persons went out to the West armed with several barrels of the mystic liquid of Sheffield and set up a razor manufactory at Bridgeport. But, alas! the precious virtue of the water evaporated in the strange land, the manufactory was closed, and Brother Jonathan, with characteristic fiscal logic, consoled himself by putting an extra 15 per cent, duty on Sheffield razors last July. As a matter of chemical analysis there is nothing more mysterious about the Sheffield water than an unusual deficiency of lime and an excessive proportion of iron, the one peculiarity being painfully obvious in the prevalence of bow legs in the town, and the other being indicated in the suggestive abundance of examples of the dentist's "dreadful trade." To return to the forge, the immersion of the knife into water is only momentary. When it is withdrawn the blade would snap like cast metal. A table-knife is required to bend like a hand-saw, and this property is obtained by " tempering," or passing the blade slowly over the fire until the elasticity required is achieved. The degrees of ductility acquired are successively indicated by the changing colours produced on the blade, these colours appearing consecutively as follows: straw, gold, chocolate, purple, violet, and blue. The bluish sheen to be observed on a table knife shows that the maximum temper is required for table-cutlery, but it may be noted that elasticity is always obtained at the expense of the hardness of the steel.

Much more might be said in a longer article than can be permitted here, of the cutlery trade of Sheffield, which, although at least six centuries old, may, if its custodians are wise, outlive six centuries more. "You may depend upon it," said Mr. Henry Seebohm, a leading Sheffield steel manufacturer, to an assembly which included Sir Henry Bessemer himself, in the London Cutlers' Hall on March 2nd, 1881, "there is nothing so dear as cheap steel;" and the same thing may be said of cheap cutlery. Sheffield has been forced into producing cheap cutlery, because the world abounds in persons who labour under the hallucination that because they can buy German scissors for sixpence a pair they have been scandalously cheated in being charged a shilling for the same article from Sheffield. But the great Sheffield firms can give all comers a long start in the competition for the permanent demand of the world for sterling cutlery. If proof were wanted, where could it be more conclusive than in the fact that America, which competes keenly in some of the neutral markets for common knives, is herself content to come to Sheffield for all her first-class cutlery and to pay a tax varying from 35 to 50 per cent, into the bargain?

Henry J. Palmer.

Related Material

- Sheffield (homepage)

- Robbed of “twenty-five years of existence” — The Trades of Sheffield and their dangers to worker's health (1866)

- A Broad Hint for a Broad-Head

Bibliography

Palmer, Henry J. “Cutlery and Cutlers at Sheffield” The English Illustrated Magazine. 1 (August 1881): 659-69. Hathi Trust version of a copy in the Pennsylvania State University Library. Web. 4 March 2021.

Last modified 4 March 2021