[Click on images to enlarge them.]

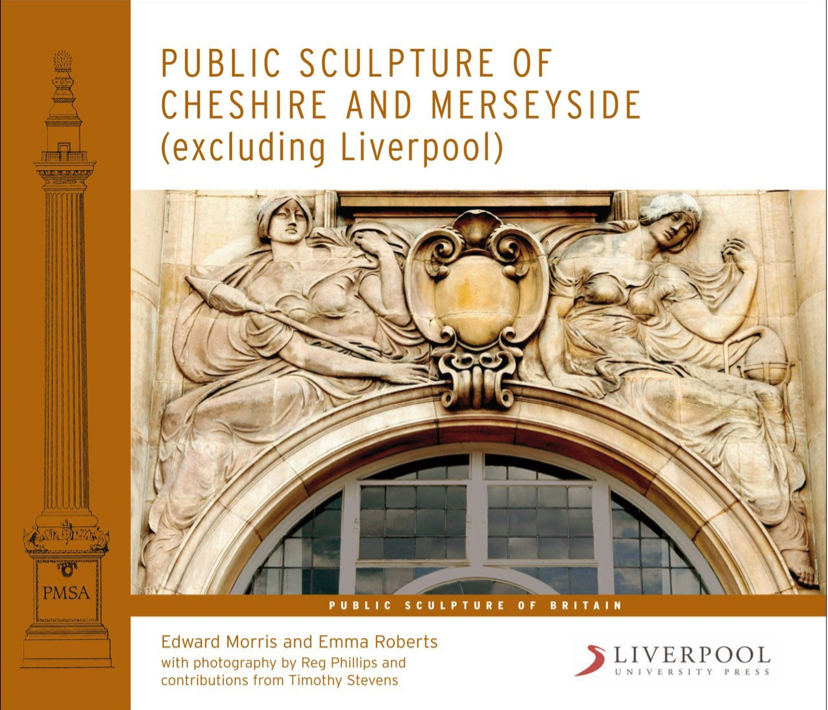

This is the fifteenth in the invaluable series on public sculpture in Britain published by the Liverpool University Press. It gives a comprehensive description of statues, church monuments, war memorials and architectural sculpture in fifty towns and villages, the major entries being on Birkenhead, Chester, Port Sunlight and Warrington.

The "statue-mania" which gripped London and other major cities in the second half of the nineteenth century made little impact on Cheshire and Merseyside. According to Edward Morris, the first major open-air public sculpture in Cheshire was not erected until 1865. Its sculptor, Carlo Marochetti, is probably better known than its subject, Field Marshal Sir Stapleton Cotton, Viscount Combermere, one of Wellington’s generals. Marochetti quoted a fee of £6,000 for the equestrian statue, while William Theed offered a cheaper version for £1,700 (plus pedestal). Marochetti was chosen, but Theed’s quote was used to persuade Marochetti to reduce his fee to £5,000.

Only three other statues by nationally-known sculptors appeared before 1900. Chester followed Combermere with Thomas Thornycroft’s rather conventional Marquess of Westminster in Garter robes (1869), while Albert Bruce-Joy’s John Laird in industrial Birkenhead (1877) shows the shipbuilder wearing the "ordinary dress of an English gentleman." John Bell’s Oliver Cromwell in Warrington is noteworthy for two reasons — it was cast in iron, not bronze, and was designed for a fountain at the 1862 International Exhibition in London. The Coalbrookdale Foundry must have been relieved when a Warrington councillor, Frederick Monk, presented the statue to his home town in 1899 to mark the fourth centenary of Cromwell’s birth.

Queen Victoria’s death in 1901 produced a trio of commemorative statues by followers of the New Sculpture" — Frederick Pomeroy in Chester (1903) and George Frampton in Southport (1904) and St Helens (1905). The citizens of Chester had originally intended to contribute to the National Memorial in London. However, when Southport decided to have its own statue monarch, Chester followed suit. Pomeroy agreed to accept a modest fee of £1,400 and worked so swiftly that Chester had the satisfaction of seeing their Victoria unveiled nine months ahead of Southport.

In Southport, the memorial committee moved more slowly. They asked Frampton for a replica of the seated figure of the queen he had recently produced for Calcutta. The Viceroy, Lord Curzon, had apparently asked Frampton not to replicate it, so Frampton offered Southport a standing figure which would be "better than the Calcutta one." The unveiling was delayed by arguments over the site and did not take place until July 1904.

Meanwhile in St Helens the wealthy glass manufacturer William Pilkington took matters into his own hands. Dispensing with public subscriptions and memorial committees, he commissioned Frampton to produce a statue based on the Calcutta model. This time Frampton raised no objection and it was unveiled in 1905. Timothy Stevens, who is responsible for the Frampton entries in the book, comments that while using the Calcutta Victoria as his starting point for the seated Victorias at St Helens, Leeds and Winnipeg, Frampton took the opportunity to "create memorials of individual character by developing stylistically different pedestals and thrones."

Left to right: (a) Inspiration, by Sir William Dick Reid, from the Leverhulme Memorial, unveiled 1930, at Port Sunlight. (b) Detail of Sir William Goscombe John's War Memorial, 1916, also at Port Sunlight. (c) Conrad Dressler's The Sower, c.1896.

Following a quartet of royal statues (the three Victorias were joined in 1904 by George Wade’s Edward VII in Bootle) it was the turn of the industrialists. The Mond Brunner Chemical Works in Winnington, known later as ICI, commissioned statues of the co-founders Ludwig Mond and John Brunner by Edward Lanteri (1912) and William Goscombe John (1922). Viscount Leverhulme, founder of the soap factory that became Unilever, is commemorated at Port Sunlight with the Leverhulme Memorial by William Reid Dick (1930), a 60 ft column surmounted by the figure of Inspiration, with other figures at the foot of the column representing Art, Charity, Education and Industry. Edward Morris suggests that a memorial symbolising Leverhulme’s virtues was chosen in preference to the more usual statue because the noble lord’s "short stature and rather formless head... were felt not to be sufficiently sculptural."

The claim by Morris that war memorials are the "most important group of public sculpture" in the area is borne out by the remarkable monuments designed by William Goscombe John and Charles Sargeant Jagger for Port Sunlight (1921) and West Kirby (1922). The Port Sunlight War Memorial combines a traditional "village cross" with eleven freestanding bronze figures of soldiers, women and children, entitled Defence of the Home; four reliefs representing the Naval, Military, Anti-Aircraft and Red Cross Services; and two reliefs of children entitled Joy in the Present and Hope in the Future. The symbolism undoubtedly reflects the views of Leverhulme on the "home front" and the role of women. Morris observes drily that the architectural elements of the memorial are "no more than a stage for the dramatic action of the soldiers, women and children, who are loosely arranged around the central cross with little regard for coherent composition or grouping."

Jagger’s Hoylake and West Kirby War Memorial is of an entirely different order. Standing on a hill with views to the Welsh mountains, the 40 ft granite obelisk has two figures at its base — Soldier on Defence and a lady symbolising Humanity. This, Jagger’s first war memorial, marked the first appearance of the sturdy and realistic British soldier — "the Tommy as I knew him in the trenches" — which in various forms became Jagger’s hallmark and features prominently on his Royal Artillery Memorial at Hyde Park Corner. While Soldier on Defence was widely praised, Humanity was less popular; the contrast between "the excesses of realism" of the former and the "extremes of idealism" of the latter was too much for some critics. As Morris notes, Jagger’s concept of Humanity may have been influenced by "the mystical wing of the New Sculpture"; but it is less obvious that there is any connection (apart from the name) with Frampton’s much criticised group with the same title on the Edith Cavell Memorial (1920).

Somewhat hidden in an appendix entitled Biographies of local artists and architects is an interesting article on the Della Robbia Pottery in Birkenhead, which for a brief period (1894-1906) produced what the book describes as "the most distinctive architectural sculpture in Merseyside and Cheshire." It was founded by Conrad Dressler and one of its leading designers was Ellen Mary Rope, a lady sculptor who deserves to be better known. A triptych plaque by her, The Word was Made Flesh, is in St Saviour’s Church, Birkenhead, and two plaques by Dressler, The Sower and The Reaper (1895), are in Birkenhead Library.

With the exception of Chester, the towns and villages of Cheshire and Merseyside are not generally regarded as being of great architectural and sculptural interest. This book, with its meticulous research, abundant photographs and entertaining descriptions, reveals many unexpected treasures.

Bibliography

Morris, Edward, and Emma Roberts. Public Sculpture in Cheshire and Merseyside (except Liverpool). Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2012. 384pp. £45.00. ISBN 978-1-8463-492-6.

Last modified 15 August 2013