Scans by the author; photographs taken and kindly provided by Robin Banerjee. You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the appropriate person and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one. [Click on all the images to enlarge them.]

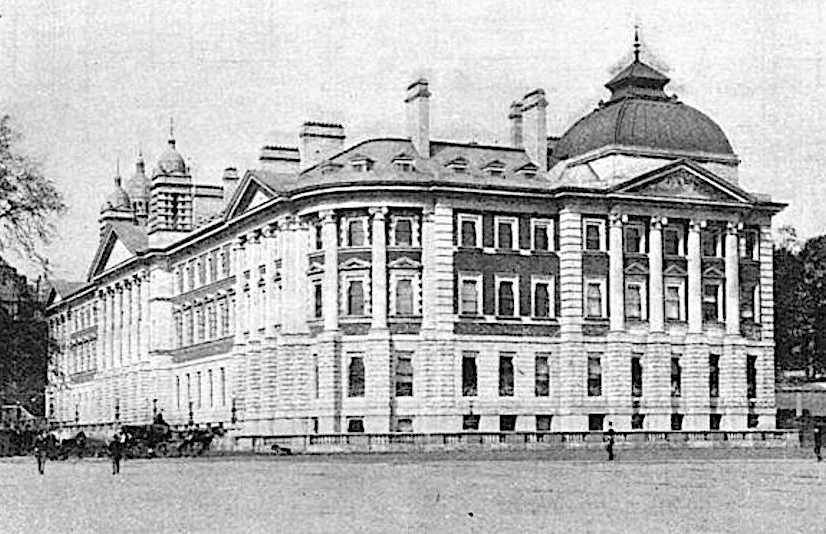

The Old Admiralty Building, now Civil Service Department Offices, currently houses the Department for Business and Trade (DBT). Its architects were Leeming and Leeming of Halifax, a partnership which also had a London office. Built 1894-95, but with further work until 1905, it is also known by the acronym "OAB," or as Admiralty Extension, and is listed by English Heritage at Grade II. In the listing text, it is described as a "redesign of their competition scheme for a much larger Whitehall Office complex." Of red brick and Portland Stone, this smaller classical building is still imposing. It has 3 storeys, basement and attic rooms, pavilions and corner towers, is set around a courtyard, and stands behind the older Admiralty building that fronts Whitehall. The elevation shown above is the familiar one that faces and forms a backdrop to Horse Guards Parade, St. James's Park and the Mall, and is seen on many ceremonial occasions. Although some have been critical of it — including the poet and Victorianist John Betjeman, who found it "hideous" (266) — others have been more appreciative, and the listing text concludes that its "Wren-like cupola-steeples and ... French square domes with copper cresting" are "important contributions to the Whitehall skyline."

Building History

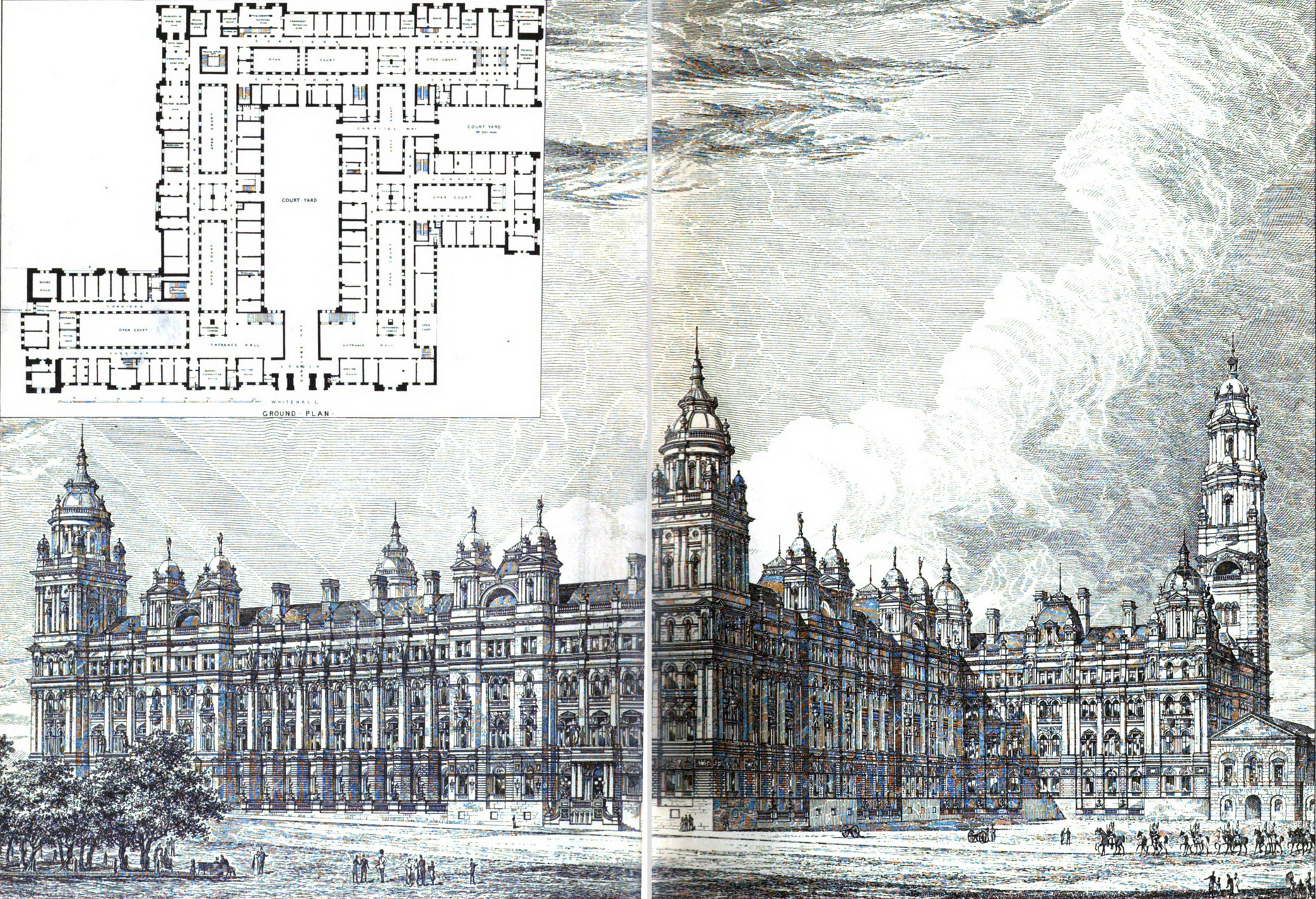

Shown here, along with its plan, is the Leemings' original, competition-winning design, as featured on a double-page spread in The Building News of 1 August 1884, 185-86. Note the long rectangular courtyard, as well as further smaller yards, and the lofty town-hall-like tower rising in several stages.

This important project was, quite literally, hard to get off the ground. As reported in The Builder of 2 August 1884, Leeming and Leeming were judged to have produced the best design for it among a large body of entrants for the commission ("The War Offices Competition," 153). But the same journal followed up this announcement with a number of unfavourable comments about everything from its scale to its details. And that was just the beginning. A huge amount of controversy, in all the relevant periodicals, followed the initial clearing of the site, and stalled further progress. Looking back nearly four years later, The Architect of 25 May 1888 quotes the venerable P.C. Hardwick as having been particularly critical of the original plan, complaining that "the whole treatment of the front is anything but a fine design" (296). The same article reveals the kind of fundamental issues that had been raised: about excavating the ground for the foundations, in case they undermined the existing buildings nearby; about its disproportionate height; and of course, about the small matter of cost.

Left: "The New Admiralty Buildings. View from St James's Park" ("New Admiralty Buildings," 119). Right: Closer view of one of the "French square domes with copper cresting," with architectural sculpture — the figures of heraldic British lions, with shields — at the corners just above the pediment.

In the end, a scaled-down version was approved. This sacrificed, for example, the plan for the tall tower that would have queened it over Horse Guards. A commentator in the Artist of 1 May 1885 had felt that the less grandiose design that emerged, whilst not ideal, and still suggestive of "a compilation rather than genius," would produce a "very creditable edifice" (148). And so it did. Concern about the foundation was addressed by its being set "somewhat appropriately in a dry dock built upon the London clay at a depth of 30ft. in solid concrete, 6ft. thick" at a cost of £23,000 — a great deal in those days, of course ("The New Admiralty Offices"). This solution was naturally of great interest to the civil engineering profession. There was also much to applaud in the lighting, heating and ventilation provisions for the building. One aspect of the final plan proved especially successful: "the building design let in plenty of light, which was essential for staff such as the Naval Constructors who were once based there, and their precise drawings" (Rowles).

In the end, then, the building proved both functional and in some ways innovative, as well as providing a picturesque setting for Horse Guards Parade from the park approach. During the war years, especially, it went on to acquire some fascinating historical associations, because of the famous people who operated from here. In short, Leeming & Leeming's contribution to this important part of London may not be Grade I listed, let alone Grade I*, but it is still a worthy part of Whitehall's built landscape.

Links to Related Material

Bibliography

"The Admiralty Offices." The Architect. 25 May 1888: 296-97. Google Books, free ebook. Web. 9 September 2025.

"Architecture and Decoration." The Artist. Vol. VI (Jan.-Dec. 1885). 1 May 1885: 148. Google Books, free ebook. Web. 9 September 2025.

Betjeman, John. Letters, 1906-1994. London: Methuen, 1984.

The Building News and Engineering Journal Vol. 47 (1884): 185-86, following on from "The New Admiralty and War Offices" (153-54). Hatii Trust, from a copy in the University of Michigan. Web. 9 September 2025.

Civil Service Department Offices (Former Admiralty Offices), Horse Guards Parade, S.W.1. Historic England. Web. 9 September 2025.

"The New Admiralty Offices." The Engineer. 31 July 1896: 119-21. Google Books, free ebook. Web. 9 September 2025.

Rowles, Natalie. "Old Admiralty Building: past, present and future workplace." gov.uk. Web. 9 September 2025. https://digitaltrade.blog.gov.uk/2022/02/15/old-admiralty-building-past-present-and-future-workplace/

"The War Offices Competition." The Builder Vol. 47 (2 August 1884): 153. ." Internet Archive. Web. 9 September 2025.

Created 9 September 2025