Click on all the following images to enlarge them, and for more information about them, their sources, and the terms of reuse. — Jacqueline Banerjee

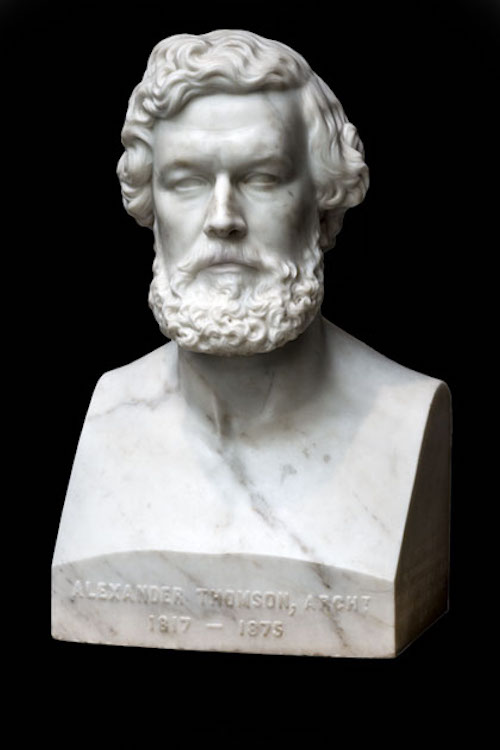

Alexander "Greek" Thomson, by John Mossman.

“YOU have to hand it to nineteenth-century Glasgow, the confident, entrepreneurial Second City of the Empire,” wrote the author of a thoughtful and well-informed article on the mid-century Glasgow architect, Alexander Thomson, in the travel section of the New York Times for 11 January 1998:

It produced two impressively eccentric architects. One, Charles Rennie Mackintosh (1868-1928), left Glasgow in disillusionment but is enjoying a huge international vogue. His master work, the Glasgow School of Art, completed in 1909, is among the city's most popular tourist attractions. The one who stayed, Alexander (Greek) Thomson (1817-1875), is known outside Glasgow mostly by architectural connoisseurs. Yet he made a much bigger impression than Mackintosh on the warp and weft of his city, devising a style both exotic and strict, peculiarly his own and peculiarly suited to Glasgow.

The close connection between Thomson’s original architectural style, Glasgow’s dynamic development in the 19th century, and the earlier and contemporary city buildings the architect lived among, as well as local Scottish writing and reflection on architecture, is explored in the outstanding contributions to a recent collective volume, “Greek” Thomson, edited by Gavin Stamp, a long time admirer and student of Thomson, and Sam McKinstry. This is currently the most extensive and authoritative study of Thomson available, along with the publications of the Alexander Thomson Society, founded in Glasgow in 1991.

Early Life and Career

Alexander Thomson was born in 1817 in Balfron, a small town in Stirlingshire, 18 miles north of Glasgow. At age seven, on the death of his father, a bookkeeper for a local cotton mill, he moved to Glasgow with his mother and numerous siblings. By 1830, his mother, his oldest sister and three brothers had also died and the remaining children moved in with an older brother, William, a teacher in a district on the south side of Glasgow. The children were tutored at home and went to work at an early age. Alexander started out at age 12 as a clerk in a lawyer’s office before being offered an apprenticeship by Glasgow architect Robert Foote, a fervent admirer of classical Greek architecture, which he had had an opportunity to study in Greece itself – an advantage not enjoyed by Thomson, who never once left the shores of the British Isles, though he was to make up for that by wide reading in architectural history and theory: notably the extraordinarily rich scholarly studies of fellow-Scot James Fergusson, the illustrated volumes devoted to The Holy Land, Syria, Idumea, Arabia, Egypt, and Nubia (1841-49) by Scottish painter David Roberts, the Principles of Architecture (3 vols. 1794) and Encyclopaedia of Architecture ( 1812-19, reissued in 1851) by architect, mathematician and engineer Peter Nicholson, yet another Scot, who was in practice in Glasgow in the first decade of the nineteenth century, and whose grand-daughter, Jane Nicholson, Alexander married in 1847, and, not least, Karl Friedrich Schinkel of whose Sammlung architektonischer Entwürfe (1819-40, republished 1841-45 and in a single volume in 1852). Thomson possessed a personal copy.

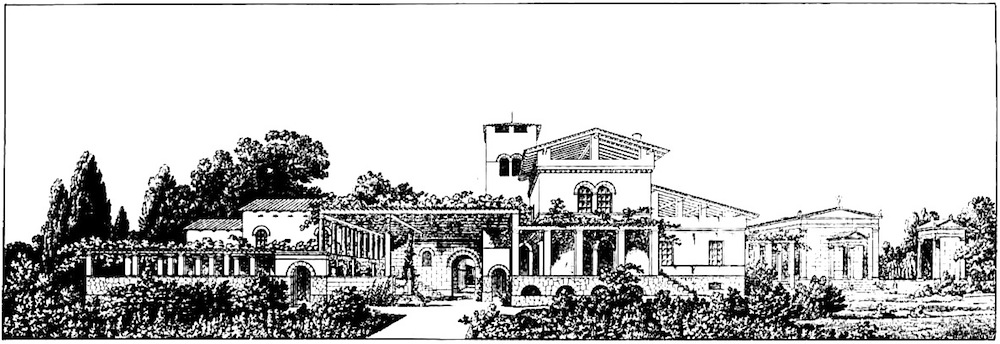

Possible influences. Left: The work of John Baird I, whom Thomson trained with and then assisted as draughtsman early in his career. Baird's Gardner's Warehouse, Glasgow, made revolutionary structural use of cast-iron. Photograph by Chris Allen, from the Geograph website on the Creative Commons (with attribution) licence. Right: The work of German architect Karl Friedrich Schinkel. Schinkel designed the Court Gardener's House at Charlottenhof, Potsdam, built 1829-35. Source: Ziller 94.

Thomson transferred from Foote’s practice to a position as draughtsman in that of architect John Baird, still well respected as the designer and builder of Garner’s warehouse on Jamaica Street in central Glasgow (1856), one of the first commercial buildings in Britain to make use of the crucial technical innovations introduced by the Crystal Palace five years earlier. In 1848, he left Baird’s to set up an architectural practice of his own, Baird and Thomson, in partnership with John Baird II, who, having married Jane Thomson’s sister, had become his brother-in-law. Nine years later this partnership was amicably dissolved and Alexander formed a new partnership with his brother George. Until then, Thomson was mostly engaged in designing and building villas for the well-to-do in the burgeoning suburban districts on Glasgow’s south side (Pollokshields, Langside, Cathcart) and in small towns and villages downriver on the scenic Firth of Clyde (Cove, Helensburgh, Kilcreggan, Rothesay). These villas, fairly conventional at first in the picturesque Italian or cottage orné styles popular at the time, gradually developed a new character through an unusual and original blending, possibly inspired by Schinkel’s sketch for a gardener’s house at Charlottenville in Potsdam, of the freedom and asymmetry of the picturesque with the discipline and order of classical Greek.

Works of Thomson's Maturity

Holmwood House (1856). Photograph by Edwardx.

Just before and especially after the new partnership, Thomson came into his own and began building widely in a variety of genres, not only villas in his new style (notably Holmwood House, 1856, now a property, open to the public, of the National Trust for Scotland), but churches, warehouses, residential terraces for the well-to-do, and tenement flats for the less well-off — in a truly original style that was unmistakably his alone and that now included elements of the Egyptian temple architecture carefully described, much praised, and copiously illustrated with sketched plans by Fergusson in his massive 2-volume Illustrated Handbook of Architecture (1855).

Left: Caledonia Road Church (1855). Photograph by Duncan Cumming, on Wikipedia. Right: St Vincent Street Free Church, Glasgow(1857-59). Photograph by Jean-Pierre Dalbéra, on Flickr.

For the United Presbyterian Church, of which he was a devout member and devoted elder he designed and constructed the monumental Caledonia Road Church, 1855 (now, after a fire and decades of neglect, in a state of drastic disrepair), the even more monumental St. Vincent Street Church, 1857-59, a category A listed building, still standing but sadly neglected, despite having been finally acquired by Glasgow City Council which has undertaken restoration, and, later in his life, Queen’s Park UP Church, 1869 (destroyed in a German bombing raid during World War II), along with some more modest structures, such as the Chalmers Memorial Free Church (1859, extended in 1873, now demolished), on Ballater Street in the Gorbals district on the south bank of the Clyde. Thomson’s ecclesiastical style was a free adaptation of classical Greek temple design, together with elements borrowed from Egyptian temple design, to create what he wanted to be a modern version of Solomon’s temple. He totally eschewed Romanesque and especially Gothic design – never much favoured in any case in Glasgow, as Daniel Defoe noted in 1726. He even published a pamphlet in 1866 — Inquiry as to the Appropriateness of the Gothic Style for the Proposed Building for the University of Glasgow – in which he took issue with Ruskin and Pugin and denounced the Gothic as expressive of centuries of decadent Roman Catholic Christianity and incompatible with the return to the original Christianity, at once free and disciplined, which he saw as the essence of his austere Presbyterian faith.

The "Egyptian Halls" (1870-72). Photograph by Thomas Annan, in the Europa Nostra photostream on Flickr.

Egyptian stylistic elements and decorative motifs were also essential to Thomson’s warehouses, several of which are still standing, though two of the most prominent are in a dangerous state of disrepair, their future uncertain. It has been suggested that one — a massive edifice opposite Glasgow Central Station sometimes referred to as the Grosvenor Building, built in 1859, and still extraordinarily impressive despite its having been somewhat disfigured by the addition of an extra storey after Thomson’s death — be rededicated as a Museum of Slavery. The other, generally known as “Egyptian Halls” (1870-72) in Union Street, not far from the Grosvenor building and, though now a category A listed building, still in extremely parlous condition — it was threatened with demolition as late as 2011 – has been under consideration for some time for conversion to a hotel. A few others, however, are still well maintained and in regular use, such as The Buck’s Head Building (1863) on Argyle Street, in the city centre, and the Grecian Building (1868) on Sauchiehall Street, also in the city centre. Thomson’s last commercial building, an office block in Bath Street in the city centre, was completed in 1875 and demolished in 1970 .

The Great Western Terrace. Photograph by Keith Edkins, on Geograph.

Elegant and restrained in design, Thomson’s residential terraces dot both the South Side suburban districts and the fashionable West End. He himself lived with his family in one of the two larger end-blocks of Moray Place (1859-60) in Strathbungo on the South Side. Also on the South Side are Walmer Crescent in Cessnock (1857) and Millbrae Crescent in Langside (1875); in Hillhead and the West End, Eton Terrace (1862) on Oakfield Avenue (1865), Great Western Terrace (1867-73), and Westbourne Terrace (1870-71).

As noted, Thomson and his company were also responsible for a number of tenement buildings, chiefly on the city’s South Side. The earliest may have been Queen’s Park Terrace (1856), which became part of Eglinton Street, degenerated into a slum, and was demolished in the course of a major slum clearance in 1980-81. One of the most handsome was constructed not at all far from Thomson’s own residence in Moray Place. This was Salisbury Quadrant in Strathbungo, completed shortly after Thomson’s death in 1875 by his last partner Robert Turnbull. A tenement in Allison Street, Govanhill, was likewise actually built by Turnbull in late 1875.

Thomson conceived of his buildings as a whole and was often also responsible for their interior design and decoration. This is most strikingly the case of the St. Vincent Street Church but Thomson’s villas also often had some degree of interior design by the architect, as, for example, at Holmwood House.

Vice-President of the Glasgow Architectural Society in 1869 and 1870, Thomson was more than a gifted practitioner of his art; he thought deeply about its nature and purpose and about the essential laws and principles by which he believed it should be governed. A selection of his Haldane Lectures, delivered in 1874, a year before his death from asthma and bronchitis, has been included, along with other tracts by him in a 200-page volume put out by the Alexander Thomson Society in 1999 under the title Light of Truth and Beauty: The Lectures of Alexander 'Greek' Thomson 1817-1875.

Bibliography

"Alexander Thomson." DSA (Dictionary of ScottishArchitects). Web. 28 October 2020. (This provides a complete listing of Thomson’s work with an excellent brief biography.)

The Alexander Thomson Society.

Aschenburg, Katherine. “The Greek’s Glasgow.” New York Times. 11 January 1998. Travel Section: 8.

Crook, J. Mourdan. The Greek Revival. London: John Murray, 1995.

Gomme, Andor, and David Walker. Architecture of Glasgow. London: Lund Humphries, 1968.

Hitchcock, Henry-Russell. Early Victorian Architecture in Britain. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1954.

Jenkyns,Richard. Dignity and Decadence. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1991.

McFadzean, Ronald. The Life and Work of Alexander Thomson. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1979.

McKean, John. "The Architectonics and Ideals of Alexander Thomson," AA Files (Architectural Association, London), No. 9 (Summer 1985): 31-44.

_____. "Glasgow: from 'Universal' to 'Regionalist' City and beyond - from Thomson to Mackintosh", in Sources of Regionalism in the Nineteenth Century: Architecture, Art and Literature, ed. Linda van Santvoort, Tom Verschaffel and Jan Maeyer, Leuven (Louvain): University of Leuven Press, 2008: 72-89.

_____. “Thomson's City: 19th Century Glasgow,” Places: A Forum of Environmental Design. 9/1 (Winter 1994): 22–33.

Stamp, Gavin. Alexander "Greek" Thomson. London: Laurence King Publishing, 1999.

_____. “’At Once Classic and Picturesque....'" Journal of the Society of Architecture Historians. 57/1 (March 1998): 40-58.

Stamp, Gavin, and Sam McKinstry, eds. "Greek" Thomson. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1994.

Ziller, Hermann. Schinkel. Bielefeld, Leipzig: Velhagen & Klasing, 1897. Internet Archive. Contributed by Harvard University (in German). Web. 1 November 2020.

Created 1 November 2020