We have on several occasions drawn the attention of readers of The Studio to certain features in the pottery of Japan which are usually ignored by students of ceramic art, although, as a matter of fact, they display evidences of the most skilled craftsmanship. The idea that art is only exhibited in pottery when it is covered with painted ornament is still very firmly impressed in the minds of many people, who would deny all aesthetic qualities of the potter's craft which do not show the painter's craftsmanship and skill. In saying this, it must not be thought that we underrate the painter's beautiful art when applied to the decoration of porcelain or earthenware; our preferences are, however, for those features which are essentially characteristic of the potter's craft — the manipulation of clays of varied texture and of coloured glazes, and of such decorative treatment as essentially belongs to the potter's art, and bears no resemblance to that of other crafts. The work of the old Japanese potters is particularly rich in these qualities. Kenzan, Ninsei, Rokubei, and many others produced wares which were full of individuality, and displayed the intimate and extensive knowledge which they possessed of their craft, and an aesthetic perception which is too often lacking in modern European and American productions.

Indeed, it is rarely that the separate achievements of any Western potter contain evidence of such comprehension and skill as may be found in those of the Far East. Yet, it may gratefully be admitted that there have been a few workers in France, Germany, and England, who, in recent years, have taken some delight in developing the true qualities of their craft, and have given to each object which has come from their hands a distinction not to examined with advantage from two points of be found in the general mass of contemporary view-one in relation to the technical qualities ceramic work. Among the honoured names of of their production, the other to the characteristics such craftsmen those of the Martin Brothers, of of their ornament. Of their technical qualities it London, are especially worthy of distinction. For many years past these artists have produced from year to year a few objects, which have been for the most part eagerly sought for by collectors and others. Much of their early work depended for its main interest on the incised decoration of birds, fish or flowers with which it was enriched. But during the last few years they have materially broadened their point of view, and have sought after and obtained many original modes of expression which lend to their productions a charm which, without being in any way imitative, recalls the work of the old potters of Japan. We shall purposely confine our remarks to these later features of their work, as we consider them to be of especial interest at this time.

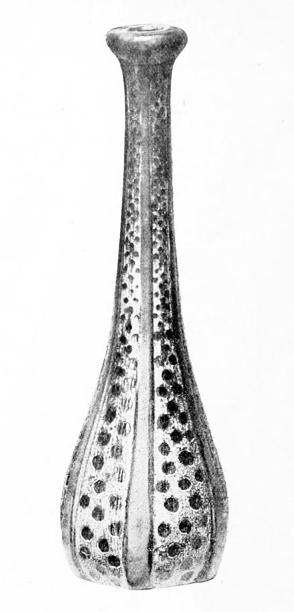

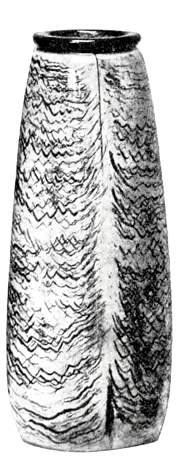

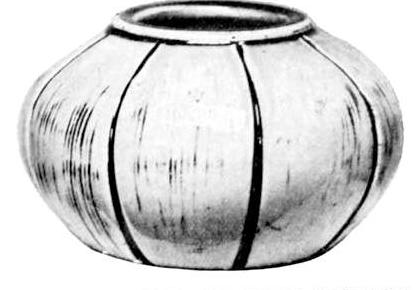

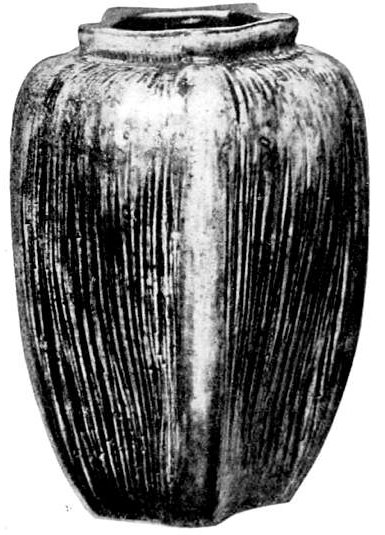

The few examples we may illustrate may be may be remarked that the earths employed, while varied in character, are uniformly dense in consistency and of excellent quality. The decoration is usually obtained by the use of "slip," either incised in the Mishima style of Japan, or applied to the surface with a brush. Salt glaze in connection with coloured enamels is judiciously employed, and the makers have been especially successful in the production of a very fine dullish black, which has all the excellent qualities of the best Chinese prototypes. The quaint and irregular shapes given to the various objects are uncommon without being bizarre. The decoration is, for the most part, intimately connected with the manufacture of the object, and not, as it were, an afterthought. In this respect their later work differs materially from some of their earlier, and is proportionately the more commendable.

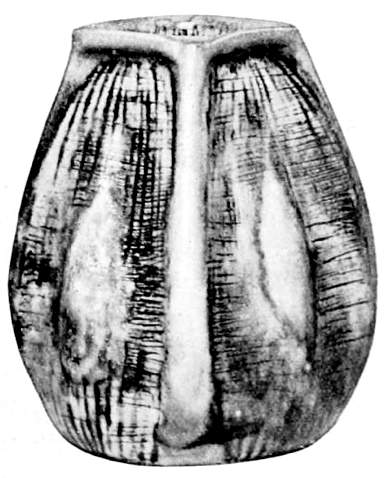

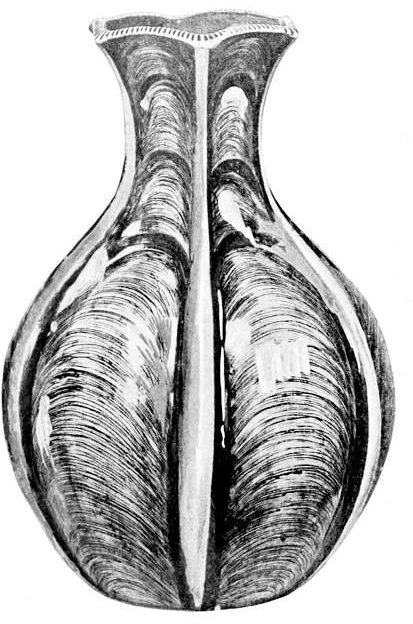

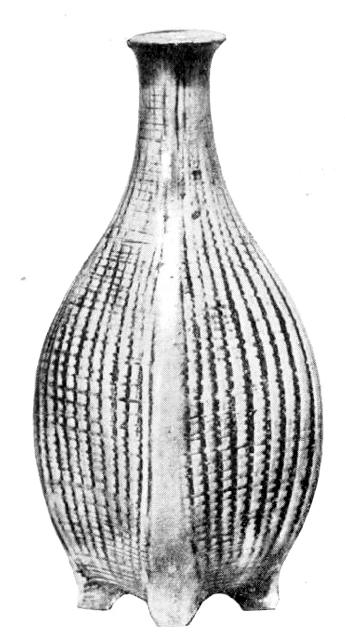

When Nature decorates her own productions, such as an egg, a shell, a flower or a fruit, she does not reproduce the forms of other natural objects. She does not paint a lily on an egg, a bird on a shell, a fish on a flower, or the portrait of a man on a fruit. Each and in doing so have borrowed many ideas from eggs and shells and other natural forms, not in strict imitation, but as suggestions for suitable ornament. For example, the "slip" decoration on Fig. 1, one of these objects has a simple type of decoration of probably more or less use to its existence, or it may be the outcome of form and growth.

Figures 1-6. [Click on thumbnails for larger images.]

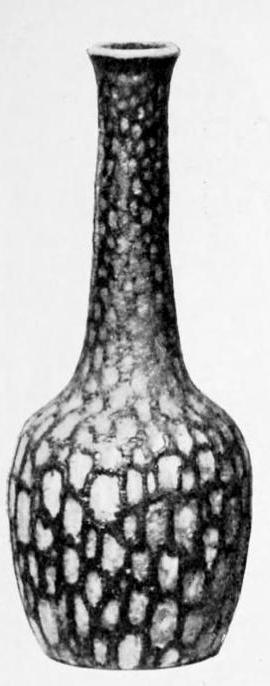

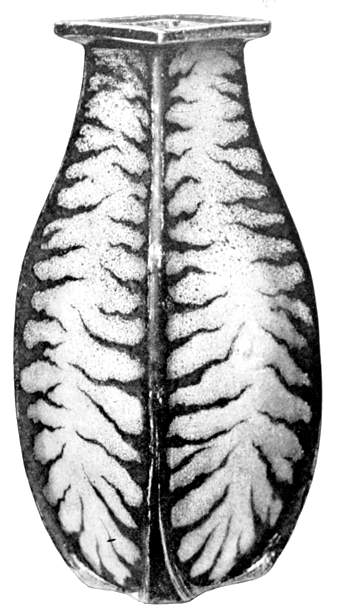

It would seem to us that the Martin Brothers, consciously or unconsciously, have endeavoured to follow these precepts of Nature, without being a copy of the markings upon a melon, seems to us to have been suggested by them; that of Fig. 2 — an excellent one to bring out the "broken" colour of running glazes — might have resulted from the appearance of a corn-cob, from which the grain has been extracted. Figs. 3, 4, 5 and 6 have characteristics of surface, form or decoration, which remind one of certain sea-shells or sea-weed; Fig. 7 displays the net-like structure of certain organisms; Fig. 8 has a texture not unlike that of a cabbage; Fig. 9, the skin of a wild animal; while Fig. 10 simulates in its colour and texture To have imitated exactly such objects would have been inappropriate and inartistic; but to have allowed them to suggest a scheme of ornamentation adapted to the technical requirements and qualities of the material is entirely permissible. The striations on Fig. 1 follow and accentuate the form of the vase, breaking up the surface into pleasant irregularity, and display the coloured enamel to great advantage. Fig. 2 is simply another device apparently selected with the same object in view. Figs. 3 and 4, with their shell-like qualities of surface, are admirable examples of the clever manipulation of glazes — Fig. 4 being, indeed, a chef d'oeuvre of the potter's art — alike perfect in potting and glazing. The striations in the panels are incised and not painted.

Figures 7-12. [Click on thumbnails for larger images.]

Incised pattern filled in with paste of a different colour to the body of the ware, which we have referred to as Mishima, was a favourite method of decoration of the old Corean and Japanese potters. It is a class of ornamentation which can only be produced by the potter himself, as it must be completed while the clay is in a damp state, before it is fired. It is one which has been somewhat neglected in Europe. In recent years the Dutch potters have practised it to a limited extent, but no work has been produced in the West of this character to compare in excellence with that of the Yatsushiro potters. Figs, 11 to 16 are types of this class made by the Martin Brothers, and they have the merit of being quite original in conception. The other examples here illustrated are selected to show a few more of the many varieties of form and treatment, and help to display the makers' power of invention and diversity of treatment.

Figures 13-17. [Click on thumbnails for larger images.]

One is apt, without careful examination, to fail to give full credit to the potter for the laborious and skilful manipulation necessary to the successful production of Mishima decoration. The Martin Brothers have been singularly happy in their efforts in this direction, and their departure in style from all previous examples is most commendable. This inlaid work is open to numerous variations and developments, and there will be no necessity for them in future years to repeat their earlier successes. And of this there need be no fear, if they continue to work upon the admirable lines they have hitherto followed.

Figures 18-21. [Click on thumbnails for larger images.]

The Martins have an excellent plan of incising in the foot or back of each piece their name and the date of its production. One may thus trace the special successes of each year, and all spurious imitations may be readily detected. By the avoidance of imitation and repetition, and by the faculty of invention and knowledge of the possibilities of his craft, there is no reason why the potter should not in the future, as he has done upon rare occasions in the past, rise to the greatest distinction as an artist, and we cannot but feel that the Martin Brothers are on the right road to such an eminence.

Figures 22-26. [Click on thumbnails for larger images.]

Our thanks are due to the Artificers' Guild, Maddox Street, London, for their permission to illustrate the examples reproduced in Figs, 1, 2, 16, 24 and 26 from their varied collection.

Bibliography

“Some Recent Developments in the Potter Ware of the Martin Brothers.”The Studio (October 1907): 108-115. Internet Archive digitized from a copy in the University of Toronto Library.

Last modified 26 December 2010