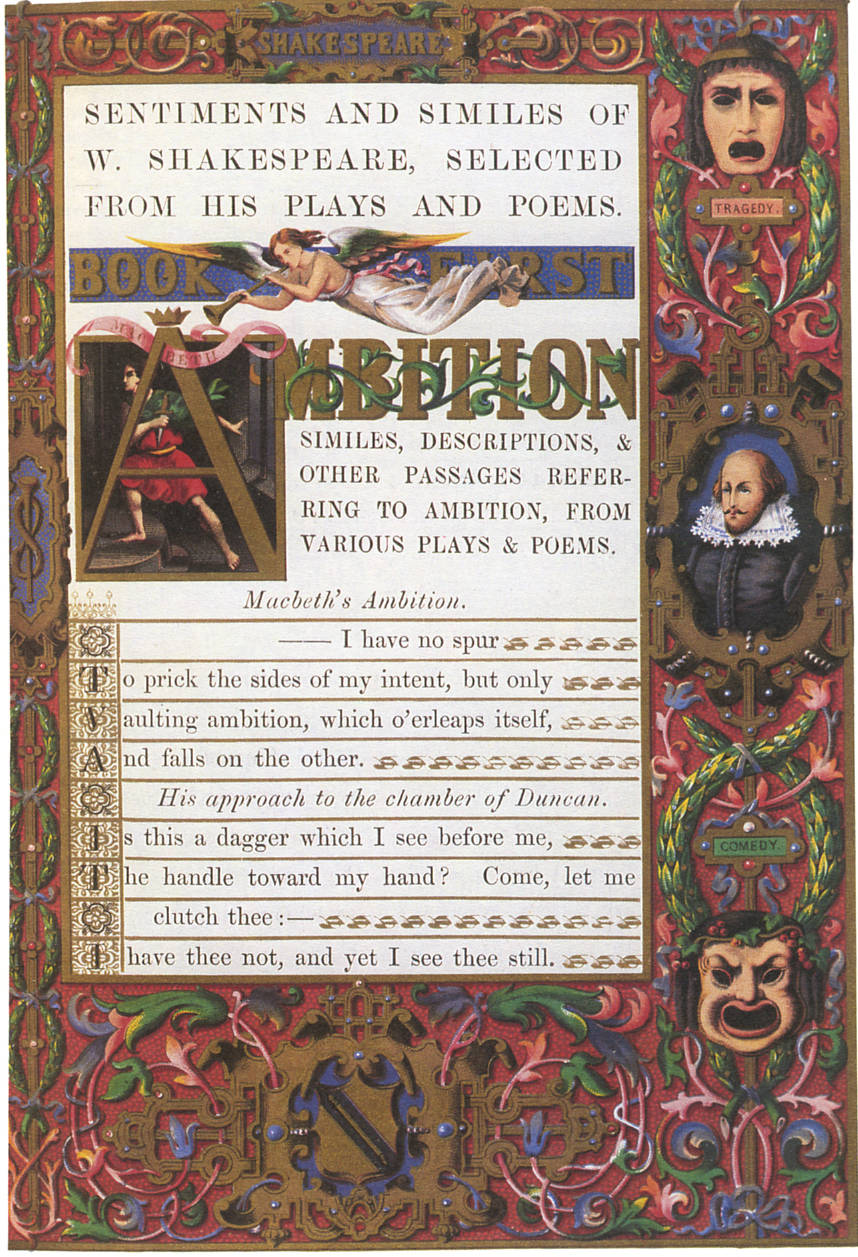

Left: Front Cover. Right: Ambition by Henry Noel Humphreys, editor and illuminator. Source: Sentiments and Similes of William Shakespeare. First edition: London: Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans, 1851. Second edition: Longman, Brown, Green, Longmans, and Roberts, 1857. Chromolithography: Engelmann & Graf, Paris. Printer: First edition, Vizetelly & Co. Second edition, Spottiswood & Co. Edition 1: 20.9 15.5 cm.; Edition 2: 19.8 x 14.9 cm. Inscription: Edition 1, “Baynes Reed/for the best theme/Bishop Walslow School/May 1852/Thoby Scard M.A. Headmaster” Beckwith, Victorian Bibliomania catalogue no. 30. Collection: Ellen K. Morris. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Commentary by Alice H. R. H. Beckwith

According to his preface, Shakespeare was the first author Noel Humphreys thought of honoring with a modern printed illuminated book. He said he wished to "enshrine [the words of Shakespeare] in a reliquary as rich as a combination of graphic and lithographic arts could form." Acclaiming contemporary advances in chromolithography, Humphreys announced that now the press rivaled the art of the hand-illuminator, as an example he cited the first page of this volume.

Although most of the illuminated ornament used in decorating sacred texts in the nineteenth century was from Gothic sources, a greater variety of ornament is found in the decoration of secular texts. Such freedom was abetted by the fact that many of most sacrosanct of British secular works, including the plays and poems of Shakespeare, were written after the Gothic age. Humphreys did not place a moral burden upon ornament as did Ruskin; rather, he attempted to be historically cognizant of the time when Shakespeare lived. He explained his choice style for the papier-mâché binding and illuminated first page being from the era of Shakespeare. Humphreys also understood the post-medieval practice of painting the richest illumination on the first page of text. His forms and placement of illuminated ornament are derived from Giulio Clovio and other sixteenth- and seventeenth-century illuminators, a group not esteemed by Ruskin although Clovio was admired by Frederic Madden and Henry Shaw (cat. 14).

The separation of historical ornament from religious and ethical teachings did not prevent Humphreys from arranging the text didactically. He grouped his quotations from Shakespeare topically under headings such as Ambition, as seen here on page 1. The evils of ambition portrayed in Shakespeare's Macbeth are suggested in Humphreys's visual analogy showing Macbeth dagger in hand, in the vignette behind the initial letter A. The border surrounding the text is in heavy grolieresque strapwork with a bust-length portrait of Shakespeare midway between masks of tragedy and comedy that are equally ominous in expression. A deep red background behind the strapwork trellis supporting elaborately entwined wreaths and vines studded with blue pearls creates an impression of luxurious splendor that accords with the theme of unbridled ambition. Humphreys shows the Victorian interest in armorial bearings by illustrating Shakespeare's punning coat of arms at the foot of the border aligned with the name Shakespeare printed at the head of the page. This volume is the result of an international collaboration: the author, editor, designer and publishers were British, but the fourteen-color border of this page was printed in Paris and then returned to London, where the roman text with gold rules, frames, initials and line endings was overprinted by Vizelley (MacLean 110).

Humphreys's enshrinement of Shakespeare's words is completed by the black papier-mâché binding with a terracotta cameo portrait of Shakespeare on the front cover and Shakespeare's initials in a similar oval on the back cover. In the first edition the pierced strapwork is placed over a striated gold foil, while the second edition has a red background and an indented bevel at the outer edge. This cover, the illuminated first page, and Humphreys's remarks about selecting ornament that Shakespeare might have requested himself reflects the emergence of an understanding that there was a difference between the style of the Middle Ages and that: of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Humphreys's knowledge, like that of John Ruskin, came from close study of many examples of book illumination. Just two years before he published Sentiments and Similes Humphreys completed his Illuminated Books of the Middle Ages, in which he had grouped all examples of illumination from the fourth to the seventeenth century together in his subtitle (cat. 16). By 1851, however, Humphreys was apparently willing to separate post-medieval works from the Gothic. Between 1851 and 1853 Ruskin published The Stones of Venice, and illuminated manuscripts figure prominently in his definitions of the difference between medieval and Renaissance arts and culture. Both Humphreys's and Ruskin's works of 1851-53 were important in developing the understanding of stylistic shifts which we take for granted today.

References

Beckwith, Alice H. R. H. Victorian Bibliomania: The Illuminated Book in Nineteenth-Century Britain. Exhibition catalogue. Providence. Rhode Island: Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design, 1987.

Friedman, Joan. Colour Printing in England, 1486-1870. New Haven: Yale Center for British Art, 1978.

Humphreys, Henry Noel, Ed. editor and illuminator. Sentiments and Similes of William Shakespeare. Henry NoelHumphreys, editor and illuminator. First edition: London: Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans, 1851. Second edition: Longman, Brown, Green, Longmans, and Roberts, 1857. Chromolithography: Engelmann & Graf, Paris. Printer: First edition, Vizetelly & Co. Second edition, Spottiswood & Co. Edition 1: 20.9 15.5 cm.; Edition 2: 19.8 x 14.9 cm.

Last modified 31 December 2013