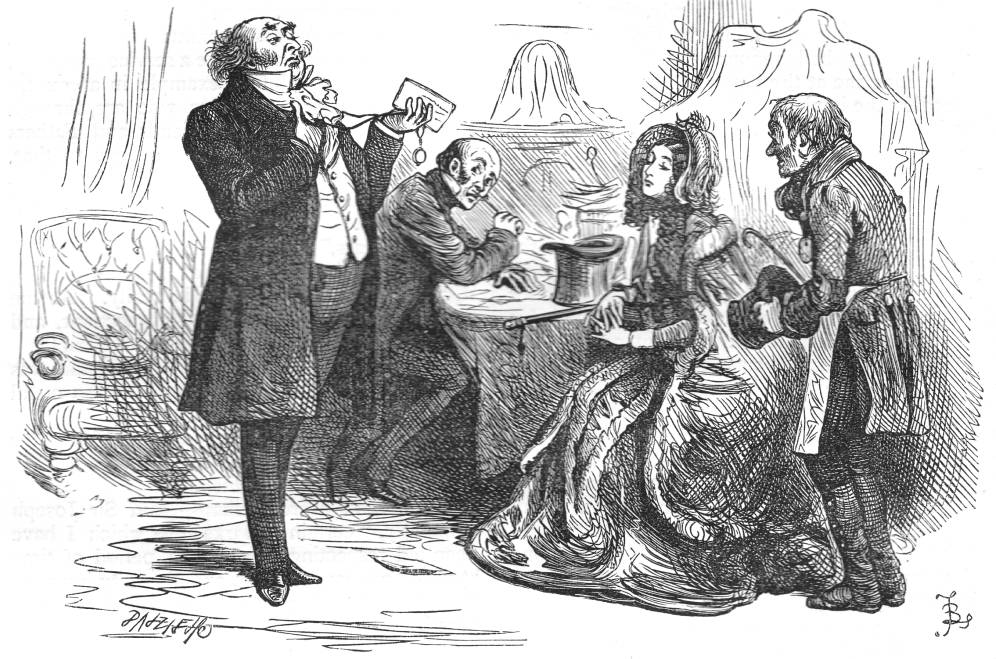

The Poor Man's Friend by Fred Barnard. The Household Edition (1878) of Dickens's Christmas Books, p. 52. Engraved by one of the Dalziels and signed "FB" lower right. Barnard's second illustration for The Chimes, The Poor Man's Friend, reveals Sir Joseph Bowley's pomposity and self-delusion as the landowner and Tory Member of Parliament receives Alderman Cute's letter, delivered by ticket porter Trotty Veck. 9.3 by 14 cm (3 ¾ by 5 ½ inches), vignetted. [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Barnard's illustration of this scene compared to that by John Leech (1844)

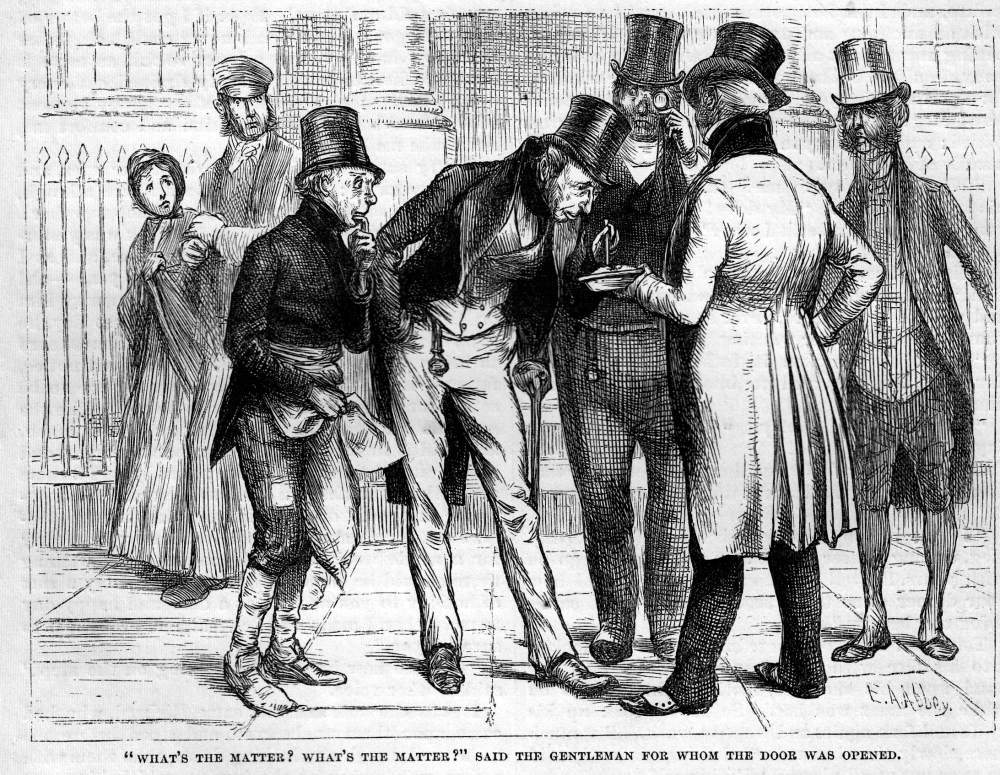

Four artists working in loose collaboration and directed by Dickens himself created the original 1844 sequence of thirteen illustrations. John Leech provided five pictures, as in A Christmas Carol (1843). His first and second woodcuts respectively depict Trotty Veck running through the streets of London, and Alderman Cute and his hangers-on confronting Trotty about the economic downside of the of a poor man's eating tripe (Alderman Cute and his Friends).

Two versions of Trotty's interacting with the governing classes. Left: John Leech's cartoon-like illustration of the Trotty's arrival at Sir Joseph Bowley's London residence: Sir Joseph Bowley's (1844). Right: E. A. Abbey's illustration of Trotty Veck's earlier encounter with Alderman Cute and his entourage on the steps of St. Dunstan's Church: "What's the matter? What's the matter?" said the gentleman for whom the door was opened (1876).

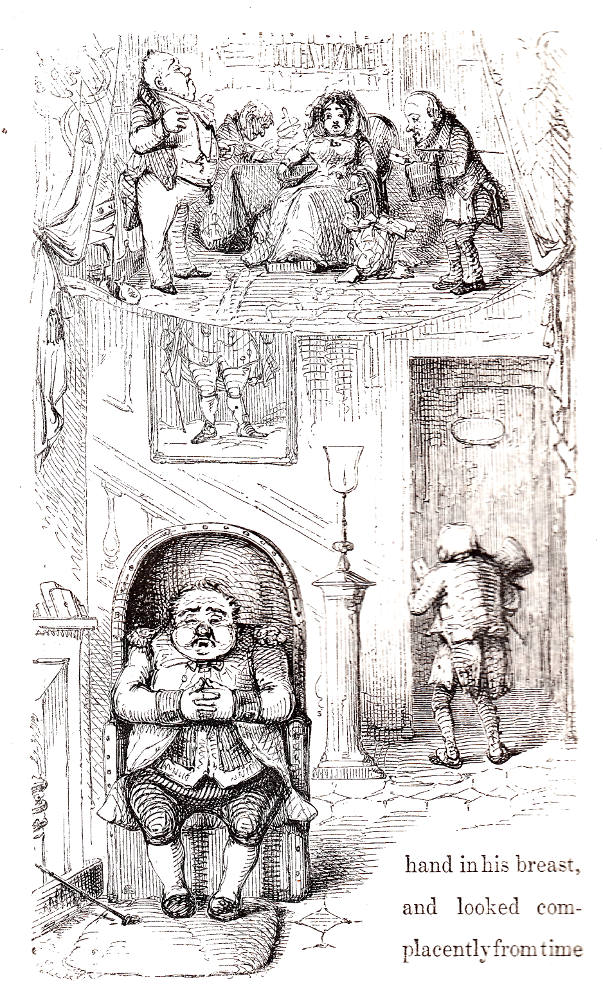

In Leech's third scene, for "The Second Quarter," the illustrator moves us from the Church of St. Dunstan's-in-the-East (originally built about 1100 A. D., but replaced in 1818, and therefore something of an anachronism in this story) on New Year's Eve to the city mansion of Sir Joseph Bowley, Member of Parliament — and in his own mind a public benefactor (Sir Joseph Bowley's). Dispensing with the Tugby scene, Fred Barnard in the 1878 Household Edition has replaced Leech's "dual" cartoon vignette at Sir Joseph's town house (lower register: the uniformed Porter, Tugby; upper register: Sir Joseph's library), which encompass two separate but related moments in the narrative, with a single, much more effective woodcut, albeit one devoid of Leech's visual hyperbole and caricature. The passage which both Leech and Barnard had in mind was the following.

Passage Realised: Urban and Rural Tories Join Forces

Toby wiped his feet (which were quite dry already) with great care, and took the way pointed out to him; observing as he went that it was an awfully grand house, but hushed and covered up, as if the family were in the country. Knocking at the room-door, he was told to enter from within; and doing so found himself in a spacious library, where, at a table strewn with files and papers, were a stately lady in a bonnet; and a not very stately gentleman in black who wrote from her dictation; while another, and an older, and a much statelier gentleman, whose hat and cane were on the table, walked up and down, with one hand in his breast, and looked complacently from time to time at his own picture a full length; a very full length hanging over the fireplace.

"What is this?" said the last-named gentleman. "Mr. Fish, will you have the goodness to attend?"

Mr. Fish begged pardon, and taking the letter from Toby, handed it, with great respect.

"From Alderman Cute, Sir Joseph."

"Is this all? Have you nothing else, Porter?" inquired Sir Joseph.

Toby replied in the negative.

"You have no bill or demand upon me my name is Bowley, Sir Joseph Bowley of any kind from anybody, have you?" said Sir Joseph. "If you have, present it. There is a cheque-book by the side of Mr. Fish. I allow nothing to be carried into the New Year. Every description of account is settled in this house at the close of the old one. So that if death was to — to —"

"To cut," suggested Mr. Fish.

"To sever, sir," returned Sir Joseph, with great asperity, "the cord of existence my affairs would be found, I hope, in a state of preparation."

"My dear Sir Joseph!" said the lady, who was greatly younger than the gentleman. "How shocking!"

"My lady Bowley," returned Sir Joseph, floundering now and then, as in the great depth of his observations, "at this season of the year we should think of — of — ourselves. We should look into our our accounts. We should feel that every return of so eventful a period in human transactions, involves a matter of deep moment between a man and his — and his banker."

Sir Joseph delivered these words as if he felt the full morality of what he was saying; and desired that even Trotty should have an opportunity of being improved by such discourse. Possibly he had this end before him in still forbearing to break the seal of the letter, and in telling Trotty to wait where he was, a minute.

"You were desiring Mr. Fish to say, my lady — observed Sir Joseph.

"Mr. Fish has said that, I believe," returned his lady, glancing at the letter. "But, upon my word, Sir Joseph, I don't think I can let it go after all. It is so very dear."

"What is dear?" inquired Sir Joseph.

"That Charity, my love. They only allow two votes for a subscription of five pounds. Really monstrous!"

"My lady Bowley," returned Sir Joseph, "you surprise me. Is the luxury of feeling in proportion to the number of votes; or is it, to a rightly constituted mind, in proportion to the number of applicants, and the wholesome state of mind to which their canvassing reduces them? Is there no excitement of the purest kind in having two votes to dispose of among fifty people?"

"Not to me, I acknowledge," replied the lady. "It bores one. Besides, one can't oblige one's acquaintance. But you are the Poor Man's Friend, you know, Sir Joseph. You think otherwise."

"I am the Poor Man's Friend," observed Sir Joseph, glancing at the poor man present. "As such I may be taunted. As such I have been taunted. But I ask no other title."

"Bless him for a noble gentleman!" thought Trotty. ["The Second Quarter"; Household Edition, pp. 49-50]

Commentary: A Comparison of the Treatments of Leech and Barnard

Although the scene in the Bowleys' "spacious library" comes a few lines after Trotty meets the Bowleys' grossly overweight porter, Tugby, John Leech has elided the two scenes into a single woodcut, placing greater emphasis on the corpulent Tugby and far less on the subsequent meeting in the library, which occupies only one-third of the page. The effect of the presentation of the two disparate scenes simultaneously is seems to imply a connection between Bowley and his porter: unable to resist the opportunity for visual satire perhaps, the caricaturist presents man and master as similar physical types, implying that both are overfed social parasites. Leech's emphasis may be founded on the fact that, later in Trotty's dream-vision, Tugby marries the groceress Mrs. Chickenstalker.

In Sir Joseph Bowley [sic] . . . Trotty is shown twice. In the bottom two-thirds of the design . . . he is walking toward a door at the back of the room in which the Porter sits. In the top third, he is handing Alderman Cute's letter to Sir Joseph. The time and place of each part is slightly different. Yet they form one unit, divided by a scarcely discernible curved line. Our expectations of pictorial art capturing a moment in time and space are somewhat distorted. Like the art of the ancient Egyptians, this technique was "not based on what the artist could see at a given moment, but rather on what he knew belonged to a person or a scene" [Gombrich 36]. In this case, the scene is Trotty's reception at Sir Joseph's. Perhaps more to the point is the way it shows a theatrical "scene." The illustration is framed by curtains pulled back at each side, and the artist has taken the same freedom as a dramatist. We accept the passage of time between scenes in a play and the transformation of characters in a pantomime. It is all part of the imaginative world in which we have agreed to take part. So too are we expected to accept the imaginative world of the text and its illustrations. [Solberg, 104]

Barnard's woodcut with a caption pointing towards a specific textual moment is somewhat smaller at 10 cm by 14 cm than Leech's uncaptioned "dual-moment" (14 cm by 8 cm). Moreover, although Barnard's "The Poor Man's Friend" shares page 52 with a considerable amount of text, it is far more focussed than Leech's. In contrast to Leech, Barnard offers a realistic treatment of the self-important Sir Joseph Bowley (left), the secretary, Fish (centre), Lady Bowley and Trotty Veck (right), all of whom are of conventional adult rather than Leech's pantomimic proportions. Treating the scene realistically, Barnard has even included the covered furniture, which suggests that the Bowleys have made a sudden journey from their country estate to town in order to operationalise Sir Joseph's New Year's ritual of paying all debts. In 1878, Fred Barnard realised (as perhaps John Leech in 1844 did not) the significance of Dickens's introduction of the member of the governing Conservative party of Sir Robert Peel into a parable about the social unrest and poverty-related issues of the Hungry Forties, and so has taken considerable pains in realising the baronet as an individual as well as a type. In Leech's illustration, Sir Joseph is merely a reflection miniature of his hideously fat Porter below: a large, neckless head surmounting a rotund(albeit expensively dressed) body. In Barnard's version, Bowley, clad in a respectable tail-coat and holding a monocle, has just received Cute's letter as he looks down his nose at the diminutive Trotty. Even though Barnard's disposition of the figures is nearly identical to Leech's, in "The Poor Man's Friend" Barnard uses perspective to create a three-dimensional space occupied by covered furnishings. Barnard subtly focusses on the aristocrat by having the other three characters turn towards him; Bowley, standing and gesturing, dominates the scene, occupying the left-hand register by himself. Barnard's representation of the land-owning class visually echoes the comfortable dimensions of the padded easy chair behind him. Barnard has turned Trotty so that we see him only in profile, and dwarfs him by placing the protagonist next to the beautiful, fashionably dressed but utterly disinterested Lady Bowley, whose skirts and fur-lined, full-length cape render her a substantial pyramid.

Scanned images and text by Philip V. Allingham. Formatting and linking by George P. Landow. [You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image, and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.

Bibliography

Cohen, Jane Rabb. Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Columbus: Ohio State U. P., 1980.

Cook, James. Bibliography of the Writings of Dickens. London: Frank Kerslake, 1879. As given in the Publishers' Circular The English Catalogue of Books.

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Books. Illustrated by Fred Barnard. The Household Edition. 22 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1878. Vol. XVIII.

Dickens, Charles. The Chimes: A Goblin Story of Some Bells That Rang an Old Year Out and a New Year In. Illustrated by John Leech, Daniel Maclise, Richard Doyle, and Clarkson Stanfield. Charles Dickens: The Christmas Books. Intro. Michael Slater. Harmondsworth, Middlesex: Penguin, 1971. Rpt., 1978. Vol. 1: 143-255.

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Stories. Illustrated by E. A. Abbey. The Household Edition. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1876. Vol. III.

Hammerton, J. A. The Dickens Picture-Book: A Record of the Dickens Illustrators. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book, 1912. Vol. XVII.

Kitton, Frederic G. Dickens and His Illustrators. 1899. Rpt. Honolulu: U. Press of the Pacific, 2004.

Patten, Robert L. Charles Dickens and His Publishers. University of California at Santa Cruz.: The Dickens Project, 1991. Rpt. from Oxford U. p., 1978.

Solberg, Sarah A. "'Text Dropped into the Woodcuts': Dickens' Christmas Books." Dickens Studies Annual 8 (1980): 103-118.

Thomas, Deborah A. Dickens and The Short Story. Philadelphia: U. Pennsylvania Press, 1982.

Welsh, Alexander. "Time and the City in The Chimes." Dickensian 73, 1 (January 1977): 8-17.

Solberg, Sarah A. "'Text Dropped into the Woodcuts': Dickens' Christmas Books." Dickens Studies Annual 8 (1980): 103-18.

Thomas, Deborah A. Dickens and The Short Story. Philadelphia: U. of Pennsylvania Press, 1982.

Created 16 July 2012

Last modified 2 January 2026