Aubrey Beardsley followed the Pre-Raphaelite Movement as a unique artist, drawing on many sources of inspiration to create his masterful black-and-white ink drawings. Beardsley painted only two known oil paintings in his lifetime, concentrating all of his talent and eager discipline towards his compositions filled with designs, patterns of decoration, caricatures, flowers, dots and bold curvaceous lines. He knew at a very young age that he would slowly die of tuberculosis, an incurable disease at the time. His clear and uncomplicated forms offset his wild subject matter of creatures of fantasy and caricatures of decadence. Some critics believe that Beardsley, like the Pre-Raphaelites, simply looks back to the past for inspiration. Originally following the Pre-Raphaelite's medieval and early Renaissance styles and then turning towards Baroque and Rococo influences. However, his attention to contemporary culture shines through all of his work, in style and subject, giving his distinct personal interpretation of Victorian life and culture.

Sir Edward Burne-Jones, Portrait of a Girl

Beardsley's direct interaction with Sir Edward Burne-Jones provided an important connection between the Pre-Raphaelites and Beardsley. Beardsley was still young and impressionable when he first met Burne-Jones, who encouraged him to pick up oil painting and medieval subject matter. The Le Morte d'Arthur drawings display Burne-Jones's early inspiration of subject matter for Beardsley. Burne-Jones' stained glass work could have also influenced Beardsley since his hometown church in Brighton, St. Michael and All Saints where he grew up, featured stained glass panels by Burne-Jones including The Flight into Egypt. Even Burne-Jones oil painting Portrait of a Girl in a green dress could be seen as an influence upon Beardsley's unique artistic medium choice. The extremely pale face stands in sharp contrast to her dark green dress and the completely black background of the painting.

Left: William Morris, Peacock and Dragon

Right: Aubrey Beardsley's cover design for Oscar Wilde's Salome

The Le Morte D'Arthur illustrations and many of Beardsley's other illustrations reflect an obvious association between Beardsley and William Morris. Morris' textile designs were gaining quick popularity in the late Victorian Period and Beardsley would have most definitely been aware of the Arts and Crafts Movement. Morris' Peacock design echoes in both the peacock chapter heading for Morte d'Arthur and in the cover design for Oscar Wilde's Salome. Although Beardsley eventually became more influenced by James McNeill Whistler and Japanese inspirations, the schematic designs of William Morris never completely exit his later work. One still sees reminiscesment effects of Morris' design in Pas les Dieux in which large flowers fill the overhanging fabric of the bed. Whistler and Japanese art, especially Japanese prints, influenced Beardsley's compositions by encouraging a flat spatial plane and a sparse use of detail. Although the influences of Burne-Jones, Morris and Whistler have been studied at length, there are many other important contemporary inspirations on Beardsley's works.

Left: Aubrey Beardsley, The Platonic Lament for Oscar Wilde's Salome

Right: William Homan Hunt, Oriana from the Moxon Tennyson

Book illustrations created the opportunity for artists to concentrate on literary subject matter that excited and motivated their visual art. Illustrations, as a medium of visual art, reached a broader audience than did paintings and sculpture. Stories, plays and poetry, accompanied by their illustrations, could be printed and reprinted to spread all over England, Europe and even into America. Famous to the mid-nineteenth century, Pre-Raphaelite artists such as Sir John Everett Millais, William Holman Hunt and Dante Gabriel Rossetti illustrated the medieval subjects of Moxon Tennyson. Holman Hunt's illustration of Oriana[The Dead Oriana] places the woman's dead body horizontally across the front of the composition. The weary lover bends over, collapsing into the dead body's face for a tragic final kiss. The man's ship sits in the background of the illustration as a small reminder of the narrative of the poem, but the moment of sorrow stands in the foreground of the piece. Beardsley delineates A Platonic Lament from Salome with a compositional layout similar to Holman Hunt's illustration. The dead man lies horizontal with the andogynous male figure leaning in to touch the corpse's head. Beardsley selects to illustrate only minimal aspects of the background in this scene, including a latticework of flowers, a neatly trimmed tree and a caricatured cloud. Besides these few elements, the background is bare. Beyond their dissimilar literary contexts, these two works compositionally put focus on very similar moments. Both Holman Hunt and Beardsley depict instances in which lust or love comes face to face with death.

Left: Aubrey Beardsley, The Woman in the Moon for Oscar Wilde's Salome

Right: Dante Gabriel Rossetti, "Golden Head by Golden Head" from the Moxon Tennyson

Some of the perverse and fantastical pictures that Beardsley created to accompany Oscar Wilde's version of the play Salome reflect an influence of the illustrations of the Pre-Raphaelite, Dante Gabriel Rossetti. Illustrations by Rossetti for his sister, Christina's poem, "Goblin Market", play with the medium of illustration to incorporate the sensations of magic and enchantment of the poem. The illustration Golden Head by Golden Head depicts the two female figures intertwined in sleep and perhaps in dream. The figures take up most of the composition and are surrounded only by a flower-patterned curtain. In the left corner of the composition, Rossetti draws a full moon with an illusion of the goblins marching through the valley with baskets of fruit upon their heads. Although not described in the poem, D. G. Rossetti places the goblins in the moon to remind the reader of the omnipresence of the evil creatures that will always be with the girls now that Laura has tasted their fruit. Analogously, Beardsley illustrates The Woman in the Moon as the frontispiece for Salome as a reminder of the magic and fantasy of the play. The male figures stand close to each other with one man standing on the other's garment. The fabric falls smoothly upon nothing, giving the figures no ground to stand on and no tangible space to occupy. Just as in Golden Head by Golden Head, the two figures appear connected in their spatial context that can only be defined by their encounters with the moon. In Woman in the Moon, thin lines create a hairline, eyes, a nose, a mouth and a flower. The moon looks towards the two people who stands at eye-level, starring back at the moon. In Wilde's play, the moon takes on an important personification, reflecting the characters' attitudes and predicting their fates. Compositionally, both Rossetti and Beardsley successfully portrait outlandish realities by placing their coupled figures claustrophobically close to enchanted moons.

Although Beardsley's illustrations share similar compositional layouts with the book illustrations of the Pre-Raphaelites, Beardsley's consistent lack of shading indicates other influences upon his style. The invention of photography greatly changed the way people perceived reality and the arts. The black-and-white photograph technology of the nineteenth century did not allow for colors and to some extent emphasized sharp contras, de-emphasizing shades of gray. More important, the application of photography to reproducing drawings used for book illustration, permitted and encouraged large areas of black and white. Beardsley's works do not attempt to create shading as opposed to the cross-hatching used in Pre-Raphaelite illustrations. Beardsley sticks to the black and white and sometimes dots to add a little delicacy to his sharp visual scheme.

Photography also created the ability to recapture reality almost effortlessly compared to recreating reality through artistic drawings or paintings. With the invention of photography, the artist of the late nineteenth-century now possessed the freedom to create things that reflect their personal vision rather than consuming their time obsessively trying to capture reality. Beardsley stated that his work was "realistic" but understood his reality to be different from most other people. He states, "Strange as it may seem I really draw folks as I see them. Surely it is not my fault that they fall into certain lines and angles" (Snodgrass p.39). Without color or shading, Beardsley's lines and angles stand out as the dominant force of style in his work.

Left: Aubrey Beardsley, Belinda in bed for Alexander Pope's The Rape of the Lock

Left: Aubrey Beardsley, Belinda in bed for Alexander Pope's The Rape of the Lock

Beardsley's black ink drawings reflect a stylistic choice to minimize clutter and unnecessary details in his works. It therefore seems curious that he would include some of the extremely decadent details of the furniture in his drawings such as seen in Belinda in Bed and The Battle of the Beaux and the Belles from the "Rape of the Lock" illustrations. Belinda in Bed features a female dressed in a oversized frilly nightgown outfit that covers her arms, shoulders and head but not her breasts. Belinda sits propped up in the middle of a gigantic pillow that lies against a gaudy headboard. Behind the headboard, swirling patterns of garlands reflect equally garish decoration of the room. In The Battle of the Beaux and the Belles, an angry female marches across the center of the illustration, knocking over a chair with her huge skirt. The chair's shape and dotted detailed pattern is reminiscent of the Furniture that gave Victorian style a bad a name. Since the use of lavish and extravagant details is featured in some but certainly not all of Beardsley's works, one must understand the furniture as a satire of the extreme and over-the-top Victorian culture.

The intense attention to women's fashion also stands out as a conscious choice by Beardsley to make decadent fashion a major motif of his paintings. The art historian, Joan Nunn describes the fashionable trends of the 1870s to the 1900s, stating that "the earlier bid for simplicity and freedom was overwhelmed by a profusion of puffs, ruchings, fringes, ribbons, drapery, flounces with additional headings and edgings, and strange combinations of materials and colours" (source). Beardsley accompanies actual fashion designs from magazines into some of his illustrations and mostly composes his female figures clothing combining a number of elements described by Nunn.

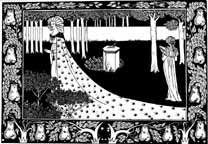

Left: Aubrey Beardsley, La Beale Isoud at Joyous Gard for Malory's Le Morte d'Arthur

Beardsley's illustration for Le Morte d'Arthur, La Beale Isoud at Joyous Gard, features the woman's dress as the central subject. The female wearing the long cape-like dress stands off to the left side, hiding behind a schematic grouping of bushes. Black ink completely fills in the grass lawn and the trees orderly line the background in a stripe-like fashion. These surroundings draw no attention towards the space but rather leave the viewer to ponder the enormous and long cape. The long cloth extends past the bottom edge of the canvas, as if to create an illusion that the cape could extend forever. Little acorns or flowers cover the fabric as eye-catching representations of nature that ironically decorates the dress as opposed to filling the landscape natural to them. The cape covers the female's entire body except for her left hand that sticks out exposing a large tassel fastened to her wrist. The tassel and the cape both look to be extremely heavy and burdensome upon the frail female figure.

Left: Aubrey Beardsley, The Black Cape from Oscar Wilde's Salome

The Black Cape for the Salome series is another example in which fashion dictates Beardsley's entire composition. The dress overwhelms the female figure, leaving the viewer unable to properly distinguish where and how the female stands under the dramatic curves of fabric. One hand reaches down in an attempt to open the layered fabric of the skirt, but is unable to control her own outfit. Black ink fills the entire dress except for a few dotted flower motifs along the bottom skirt and upon the shoulder puffs. Her shoulder puffs are extremely exaggerated with six layers of fabric covering each other like scales on a snake or wings of a butterfly. Salome's thinly delineated profile sits under a large bulky hat-piece that rests uncomfortably on her head. Upon close inspection the hat piece appears to have an ear and mask. The exaggerated dress design and masked headpiece create the possibility that this outfit is a fanciful butterfly costume. A Beardsley scholar, Milly Heyd discusses the use of butterfly in other Beardsley works and the use of a butterfly as Whistler's signature. According to Heyd, the butterfly symbolizes independence and also has been defined by the Oxford dictionary as a term used to describe "a vain gaudily attired person" (122). Beardsley perhaps creates a complex image of Salome in which she attempts to dress to reflect her independence yet her attempt is in vain, as she ends up appearing ridiculously at the mercy of her unmerciful dress.

Pierre Bonnaud, Salome

Heyd describes the claustrophobic and controlling nature of the dress in The Black Cape: "Costume becomes a method of controlling the feminine personage, imprisoning it by means of yet another layer imposed on an already layered fashion" (120). Beardsley created the smothering outfit in The Black Cape without any reference or description of such an outfit in the play. In contemporary versions of the same subject by other artists, Salome wears transparent garments that allow for her naked body to be exposed to the viewer. Gustave Moreau's Salome of 1876 and Pierre Bonnaud's Salome both depict a sexually charged female using her striking body to get what she wants. Conversely, Beardsley's Salome's body is hidden under a "burlesque of nineties vogues in dress...It could have offended no one except a reader who expected the illustrations to have some connection to the text" (Weintraub, 72). Beardsley's inventive illustration of Salome demonstrates his acute interest in the powerful, reckless and extravagant Victorian fashion.

Beardsley's own interpretation of the classic Cinderella story, appearing in The Yellow Book of July 1894, clearly personifies the powerful role that fashion has within a society. Beardsley changes the ending of the story to turn happy children's fairytale into a murderous mess of fashion and jealousy. Beardsley's version thus addresses the reader,

You must have heard of the Princess C. with her slim feet and shining slippers. She was beloved by the prince who married her but she died soon afterwards poisoned according to Dr. Gerschovius by her elder sister Arabella, with powdered glass. It was ground I suspect from those very slippers she danced in at the famous ball, for the slippers of Cinderella have never been found since. [Quoted Heyd 123]

This literary source, combined with the close inspection of La Beale Isoud at Joyous Gard and The Black Cape, suggests that Beardsley believed that Victorian fashion was a dangerous and powerful means to control and constrict women.

Beardsley explicates the momentous role of cosmetics in Victorian culture through his many depictions of "toilettes" or dressing tables. Similar to the focus on women's fashion, Beardsley's toilette scenes resonate the wildly vain Victorian culture of beautification. In Volume III of The Yellow Book, the drawing La Dame aux Camélias (or Girl at her Toilet) features a girl's head sticking out of the top of an exaggeratedly puffy coat with swamping sleeves and a tail that falls down to her knees. Beneath the coat, the girl wears a fancy patterned dress. She stares into a mirror that is only visible on the very edge of the drawing. The mirror rests upon the girl's dressing table, accompanied by two candlesticks and at least eleven different small boxes. Beardsley drew the girl's toilet in great detail even though the floor of the room in which she stands is not even delineated. According to one Beardsley scholar, these small boxes all had distinct purposes,

each no doubt represented its particular perfume...This little box contains Circassian Rose Opiate for the teeth. Another, powder, scented Wood Violet or Mar�chal... diamond- or cane-cut; silver-mounted vessels containing hair-washes, pomades; restorers of all kinds; smelling-bottles; pin-trays in ruby, opaline, amberina; fan-cases, silk-covered, silk-lined. [Easton 126]

The different boxes represented in Beardsley's toilette depictions do not reflect any direct artistic influence but rather exemplifies Beardsley's intense attention to the Victorian consumer culture around him.

All these specific boxes represent contemporary trends in makeup and hair in Victorian England. Although these trends could be considered excessive luxury items, they play a very specific role in giving hope to women who wish to improve their looks or women in fear of the transience of their natural beauty. The Beardsley toilette images mock a consumer culture in which technology can be mass-produced to feed the upper and middle classes' aesthetic interests. Max Beerbohm made a strong commentary in his "A Defence of Cosmetics" (text) in 1894 in which he justifies the excitement around cosmetics as a new chance for the female face to be beautiful. Mocking romanticism, Beerbohm claims, "Too long has the face been degraded from its rank as a thing of beauty to a mere vulgar index of character or emotion...I have no quarrel with physiognomy... But it has tended to degrade the face aesthetically" (117). The woman described by Beerbohm is more of an object to be viewed than a person to be understood. Beerbohm states that with makeup, "we shall gaze at a women merely because she is beautiful, not stare into her face anxiously, as into the face of a barometer"(117). Like the fashionable clothing of the late-nineteenth century, the burst of growth in the makeup industry allowed for women to cover their natural selves under a mask. The more the female covers herself away physically with clothing, makeup and accessories, the more she becomes a commodity or an object of the male gaze.

The mirrors in Beardsley's toilette scenes generally appear on the edges of the drawings so that the viewer is unable to see the reflections. Heyd hypothesizes that Beardsley does this because he does not "wish to show the lady (or society) her true face. Thus, suggesting or perhaps questioning our capacity to look at ourselves in the mirror"(128). The reflections of the mirrors seem ironically insignificant in these toilette scenes. The drawings focus on showing the considerable efforts and processes of the Victorian women in trying to become beautiful with the use of artificial products.

The toilet scene reaches its most powerful state in Beardsley's poem "The Ballad of a Barber." The poem describes the ludicrous amount of success and power that the fictional hairdresser, Carrousel has upon his society. Carrousel cuts the hair of the royalty, and by the time the reader meets him in this poem, has perfected his skills down to a systematic scientific art.

Such was his art he could with ease

Curl wit into the dullest face;

Or to a goddess of old Greece

Add a new wonder and a grace.

All powders, paints, and subtle dyes,

And costliest scents that men distil,

And rare pomades, forgot their price

And marvelled at his splendid skill.

The curling irons in his hand

Almost grew quick enough to speak,

The razor was a magic wand

That understood the softest cheek.

At this point in the poem, Carrousel encounters a young girl whose hair turns out to more than he can handle:

Three times the barber curled a lock,

And thrice he straightened it again;

And twice the irons scorched her frock,

And twice he stumbled in her train.

His fingers lost their cunning quite,

His ivory combs obeyed no more;

Something or other dimmed his sight,

And moved mysteriously the floor.

He leant upon the toilet table,

His fingers fumbled in his breast;

He felt as foolish as a fable,

And feeble as a pointless jest.

Frustrated by his failure to tame nature, Carrousel is suddenly taken over by a strong and mysterious urge:

He snatched a bottle of Cologne,

And broke the neck between his hands;

He felt as if he was alone,

And mighty as a king's commands.

The Princess gave a little scream,

Carrousel's cut was sharp and deep;

He left her softly as a dream

That leaves a sleeper to his sleep.

He left the room on pointed feet;

Smiling that things had gone so well.

They hanged him in Meridian Street.

You pray in vain for Carrousel.

Carrousel's murder of the beautiful Princess asserts the ultimate male authority over the female body. The King's own daughter appears as an almost inanimate object to be both played with and killed without any say in the matter. The murder also represents the decadent's fear of nature and the natural. Third, because Beardsley's constant health problems kept him in a state of waiting for his own death, he could have seen his power over the arts as similar to Carrousel's -- a delicate power that would be completely shattered at any time with his own premature death.

Aubrey Beardsley's two versions of The Toilette of Salome from Oscar Wilde's Salome

In the two Toilette of Salome illustrations, Beardsley places a shelf of books in the foreground of the work. The viewer may easily read the books' titles, hinting at their importance. The grouping of French books in the second version of this illustration includes Zola's Nana, The Golden Ass, Manon Lescault, Marquis de Sade, and Les Fetes Galantes. Heyde believes that these different sources connect to some of the personal fear and paranoia of Beardsley's life (133). In addition, by placing these very specific books into his illustration Beardsley pronounces that, "life should imitate art and that the ideal is to live life 'against nature'"(132). The artist interacts with his contemporary audience by placing other forms of social thought into his work as an instructional or referential addition. He also includes them to shock a middle-class audience by citing works favored by the Aesthetes and Decadents.

The fin-d-siècle in Victorian culture was an extremely decadent period, not only in the fine arts, but in the popular culture. Aubrey Beardsley rises to the surface of this culture, first imitating elements of contemporary Pre-Raphaelite artists such as Burne-Jones and Rossetti, and finally finding his own unique style of art and interesting interpretation of Victorian culture. Beardsley died in March of 1898, at the young age of twenty-five. He would have perhaps been shocked and pleased at his great influence on the art of the twentieth century. A fine example of his immediate influence can be recognized in the designs of the Glasgow Four. This group of designers and architects included Charles Rennie Mackintosh, James McNair, Magaret and Fances MacDonald. Mackintosh repeatedly used motifs of thinly outlined female heads and flowers in his furniture designs that unfurl the similarities between his works Beardsley's pieces such as The Woman in the Moon. In 1900, Mackintosh and his wife Margaret were commissioned to design the Ingram Street Tea Rooms. The two artists included very large frescoes for the Tea Rooms including Margaret's The Queen May which is also commonly displayed in its gesso cartoon form that was created for the fresco. A female head rises out of a tear shaped bubble that is reminiscent of a puffy Victorian skirt. Thin clean lines and small jewel-like flowers decorate the female's surroundings without given her any space or time. This female figure not only mimics the shape of Beardsley's figure inThe Peacock Skirt, but also mimics the Victorian woman's aura as seen through the eyes of Beardsley. The woman stands inanimate, without emotion or personality, hidden behind fabric and rouge as an object of decoration and pure aesthetic pleasure.

Works Cited

Beardsley, Aubrey. "Ballad of a Barber." The Victorian Web. December 2004.

Beerbohm, Max. "The Pervasion of Rouge." The Victorian Web. December 2004.

Brophy, Brigid. Beardsley and His World. London: Thames and Hudson, 1976.

Easton, Malcolm. Aubrey and the Dying Lady. London: Secker and Warburg, 1972.

Heyd, Milly. Aubrey Beardsley: Symbol, Mask and Self-Irony. New York: Peter Lang, 1986.

Nunn, Joan. "Victorian Women's Fashion, 1870-1900: The Skirt." The Victorian Web. December 2004.

Weintraub, Stanley. Aubrey Beardsley: Imp of the Perverse. University Park: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 1976.

Last modified 7 April 2005;

Thanks to Lauren Johnson for correcting an error.